Life by Design

“I’m going to repurpose my time doing things that I find meaningful,” says Burnett, a product designer, who with Dave Evans wrote the bestselling book Designing Your Life: How to Build a Well-Lived, Joyful Life.

The authors, both Silicon Valley veterans who worked on creative teams for Apple, developed Stanford’s Designing Your Life course, as well as workshops for people retooling their careers, considering encore professions, and planning for retirement.

Burnett is applying the same design thinking he used to create the latest technology and products to prepare for the next phase of his life.

“Designers think differently than other people,” says Burnett, executive director of the Design Program at Stanford, where he oversees the undergraduate and graduate product design programs. They approach problems with curiosity, reframe dysfunctional beliefs that hinder creativity, prototype ideas to figure out what works, and form radical collaborations with others.

“People can use these design tools as they move from the money-making phase of their lives to the meaning-making phase,” he says.

Too often busy professionals don’t give enough thought to retirement, finding themselves adrift after leaving careers, Burnett says. “At work, they have a social network, status, a role they play in the organization. The day after they leave that job, they are just somebody sitting in a Starbucks drinking a coffee. It’s pretty jarring for people who haven’t prepared for it or designed for the change.”

Burnett says people preparing for retirement often use one of three strategies:

All these strategies require designing your way forward, he says.

Explore New Ideas

To begin the process, many people must overcome the fear of leaving their job, which often provides them with their identity, routine, and relationships, says Kathy Davies, managing director of the Life Design Lab at Stanford. The teaching lab runs the university’s Designing Your Life classes, develops the life design curriculum, and trains other universities to teach life design.

One key to making this leap is using your curiosity to explore several ideas, Davies says. “People need to reframe the dysfunctional belief that there is just one good direction in retirement. There are many.”

To help you get started, the Stanford experts suggest that you:

- Write a short reflection of 250 to 500 words about your future. This is a general statement of what you consider good and worthwhile in work, where work is not necessarily a paid endeavor but how you use your time and energy to accomplish things in your life and community, Davies says.

- Write another 250 to 500 words about your view of life. These are your critical defining values—what matters most to you, the meaning and purpose of your life, and how spirituality, family, where you live, and the rest of the world fit into your life.

- Review your statements and see where your views complement each other and where they clash.

These two views are your compass for your life and future.

Outline Your Plans

Burnett suggests developing three Odyssey Plans for yourself. Keep a journal and write down the times you feel energized about your life. Consider what you would do in retirement if you didn’t have to worry about money or the possibility of someone laughing at you for doing it.

Create three wildly different five-year timelines filled with activities you might pursue. Developing these three future visions helps people brainstorm ideas for their future, he says.

Maybe you want to become a bartender in Belize or a clown in Cirque du Soleil, Burnett says. “We are not encouraging you to sell the house and join the circus. We’re telling you to let your imagination go for a while.”

Davies says having several routes to explore can open new possibilities and set you free from perfectionist tendencies that could limit you.

Test Your Ideas

After you have plans, prototype some of your ideas, Burnett says. One of the easiest ways to do that is to talk to someone who is living the type of lifestyle you’re considering.

Testing your plan requires a small investment of time and can lead to a big payoff in the long run, Davies says. “The magic of prototyping is that instead of sitting around and talking about your plan, you do something. You get out of your head and into the world to try things.”

Davies worked with a retired couple who planned to become what they called silver-haired gypsies by selling their home and touring the U.S. in an RV. They tried it out for a week and found they loved RV life but didn’t like all the driving, so they decided to take occasional trips and maintain a home base.

People sometimes pay a high price for not prototyping an encore career. One example is a woman who left her job in human resources for a large corporation to fulfill her dream of opening a small Italian deli and café. She renovated the space and launched her business. Her café was successful, but she was miserable. She didn’t enjoy hiring staff, tracking inventory, and ordering stock.

The former human resources professional could have avoided a costly mistake by interviewing small café owners, bussing tables at an Italian deli, or working for a catering business. Eventually, she sold her business and went into designing restaurant interiors, which was her favorite part of opening the café.

Burnett suggests giving yourself time to make the transition into retirement. Some people take at least a year’s sabbatical after they leave their jobs before they try something new. He has a friend who retired from his career as a venture capitalist, a lucrative but stressful job. He told Burnett, “I plan to take three years to ride my bicycle and read books because I don’t want to make a decision about the future with a burned-out brain.”

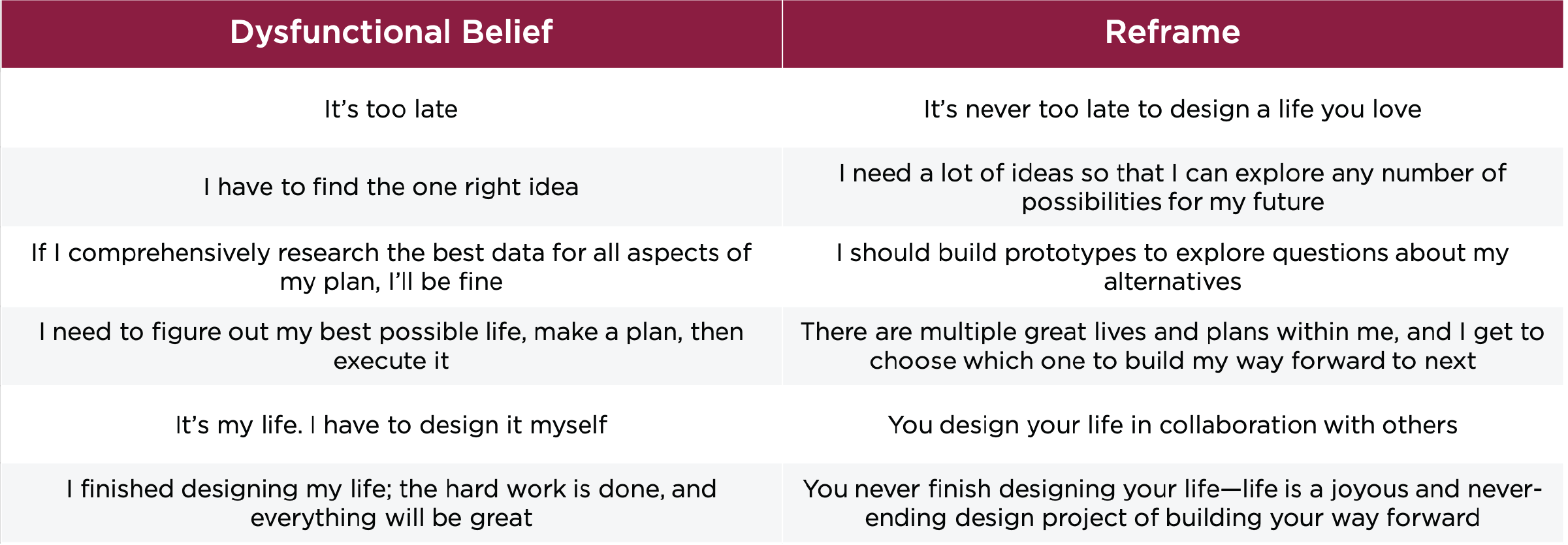

Reframe Your Dysfunctional Beliefs

One of the keys to a well-designed life in retirement is reframing some of your dysfunctional beliefs to create a better life for yourself. Here are some examples, according to Designing Your Life: How to Build a Well-Lived, Joyful Life:

Ask for Help

No matter what your retirement plan is, it’s important to form radical collaborations, Davies says. Talk to your spouse and other people who have retired or are considering it, she says. Get input from people who have different perspectives.

Davies says one woman she worked with created three Odyssey Plans for retirement but didn’t know if her husband would be supportive of some of her more creative ideas. It wasn’t until he also outlined some plans, and they shared ideas, that they both fully appreciated one another’s dreams and began working on plans together. Their lists created lively conversations that helped them prepare for the next stage of their lives.

Burnett has been talking to his wife and others about the future, as well as prototyping some of his ideas. Eventually, he’s going to step back from some of his administrative roles but wants to continue to teach. “I love teaching, I love writing, and I love art.”

He is prototyping his future life with a small art studio down the street from his home. He plans to write a book on designing your life for retirement, and he has other creative projects he’s discussing with potential collaborators.

“I am going to spend the next 10 or 20 years doing something interesting,” he says. “I’d like to hang out more with artists and musicians. I’ve got at least two more lives in me.”