Proactive Spending Policies for Times of Volatility

For endowments and foundations, the goal of any spending policy is to balance current needs with long-term financial health. To meet that goal, governing boards often design spending policies that prioritize perpetuity and consistency above all else, with spending as a percentage of total assets remaining constant year after year. But when markets dip or swell outside normal ranges—reducing or increasing assets in unexpected ways—board members may feel tempted to react and reevaluate the organization’s baseline spending policies.

Depending on the circumstances, straying from predefined spending policies may be a good idea for some organizations. What’s key is to understand both the long- and short-term impacts of any potential change, and that can be difficult to do in the moment.

To better prepare for volatile market behavior, CAPTRUST experts recommend endowments and foundations run stress tests to model different scenarios when establishing spending policies. What will the organization do if a market rally creates a 20 percent asset growth in one year? What will it do if a market pullback reduces asset value by the same amount? In these cases, for some organizations, creating conditional spending policies with provisions beyond the core distribution target for each asset pool may make sense.

For those who are involved in making spending policy decisions, here are a few best practices and examples to consider when designing conditional spending policies.

Plan Ahead

A conditional spending policy is designed to encourage an organization to think proactively, not reactively, says Wally Terrell, senior specialist on CAPTRUST’s asset and liability team. “If certain conditions happen in the market, like outsize gains or the recent dip in both stocks and bonds, then spending is adjusted based on pre-planned conversations. This way, board members can be sure they’re not making knee-jerk reactions without considering the long-term perspective.”

Modeling assists decision makers in understanding how different events can affect the organization and how the organization will react. It also helps ensure the organization is aware of—and comfortable with—spending policy implications to its portfolio and mission.

It is important to keep in mind that adding conditional spending policies to an investment policy statement (IPS) does not mean the organization will be locked into these provisions. Conditional spending policies simply become another part of the organization’s comprehensive investment strategy, named within the IPS alongside other portfolio parameters and strategic principles, such as the organization’s investment objectives, constraints, and reporting requirements.

As a best practice, the IPS should be reviewed at least annually and any time there is a material change in the organization’s circumstances. As Grant Verhaeghe, endowment and foundation practice leader at CAPTRUST, explains, “When a triggering event occurs, board members can confirm in committee meetings whether the decision made in anticipation of this event is still the one they continue to believe is the right course of action, or not.”

There is nothing suggesting that the organization can’t change course, so long as it follows applicable tax codes, honors donor intent, and aligns with legal compliance in the context of long-term objectives.

Create Overlap

Another best practice is to integrate the organization’s spending and investment policies by creating overlap in the teams that design them. Ideally, the people who are making spending decisions will be some of the same people on the investment committee so that both groups are aware of what is happening in both areas.

“At a minimum,” Verhaeghe says, “the IPS ought to reference the spending policy, if they are separate documents. Organizations might also consider creating a single document that encompasses both policies.

“It’s even better,” he says, “if an organization can create overlap between the committees that are making these decisions, because overlap creates better information and leads to better financial decisions.”

Terrell agrees: “Allocation decisions should be codified in the organization’s IPS, and everything should revolve around the mission. Spending policy, investment policy, the mission—they should all be in harmony.”

Customize the Plan

Although planning itself is a consistent best practice, there is no fixed way to establish a spending policy. Every organization is unique, which means every IPS will be unique, and the conditional spending policies included in that IPS can be infinitely customized. “There is so much flexibility,” says Terrell. “The key is to think about the organization’s unique mission and how its assets support that mission.”

As Verhaeghe explains, “The right spending policies will depend on how the organization utilizes each pool of assets for its ongoing needs.”

In other words, committee members need to understand the organization’s financial vulnerabilities and how different market conditions will impact its mission. For example, some foundations rely heavily on one asset pool, while others depend on grants and donations. The latter will have more flexibility to take investment risks but will also likely see donations decline while markets are down.

Terrell says one widespread practice is to apply different spending policies to each asset pool. For instance, he says, it’s common to have asset pools that function as reserves. Typically, these funds are invested conservatively and may grow slowly over time. In this case, Terrell says, “The foundation may decide to institute a conditional spending policy that says ‘When assets in this pool exceed a certain amount, the organization may institute a simple spending policy. But if assets do not reach the target, there is no spending from this pool whatsoever.’”

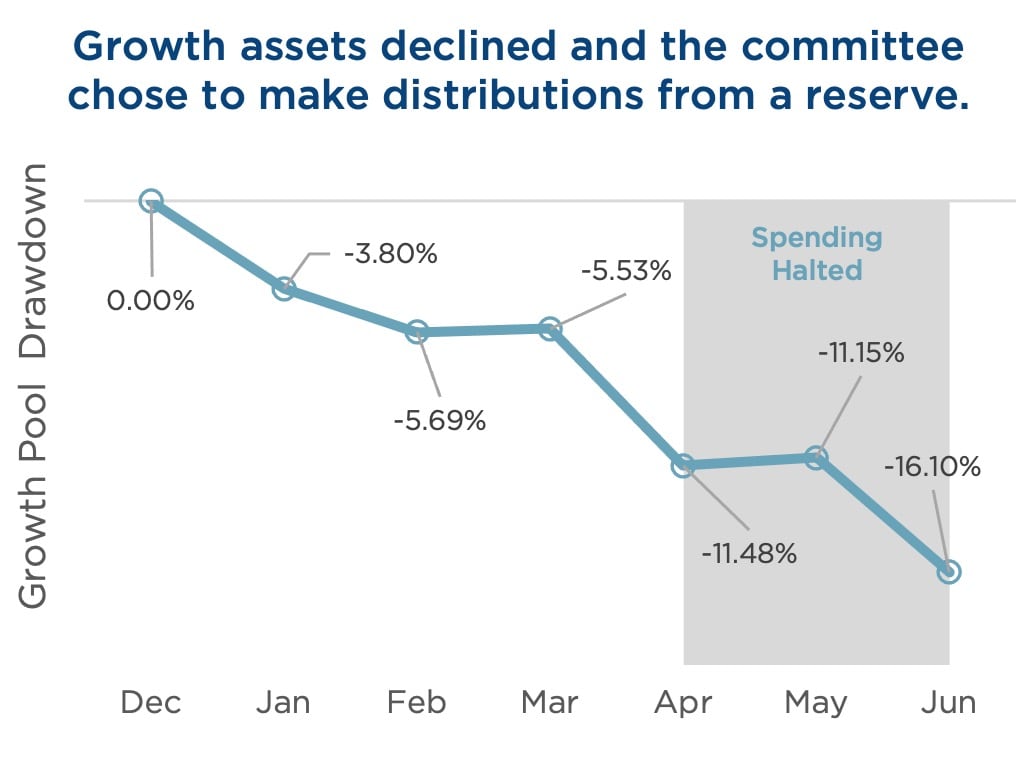

One of the more unusual types of IPS spending policies Terrell has seen is from a client that has, essentially, a growth portfolio and a separate, capital preservation portfolio with a more conservative investment strategy. “Their policy is that if the equity markets decline by more than 10 percent, then instead of distributing from the bigger, growth-focused portfolio, they would instead spend from the more conservative portfolio,” he says. “This way, they don’t unnecessarily deteriorate their equity assets and can use the market downturn as an opportunity to become more tactically aggressive than they otherwise would be under normal spending behaviors.”

Verhaeghe elaborates: “It’s like saying, ‘I don’t want to sell growth assets in a distressed environment.’ Their spending policy means they can hold onto growth assets when market valuation is better.”

As examples of how market conditions may influence mission-centered spending behaviors, Terrell and Verhaeghe offer three case studies for consideration. Note that these examples do not consider regulatory spending requirements that apply to some nonprofits, nor are they meant to serve as ready-made examples for adoption. The right conditional spending policies for each endowment or foundation will depend on that organization’s unique goals and circumstances.

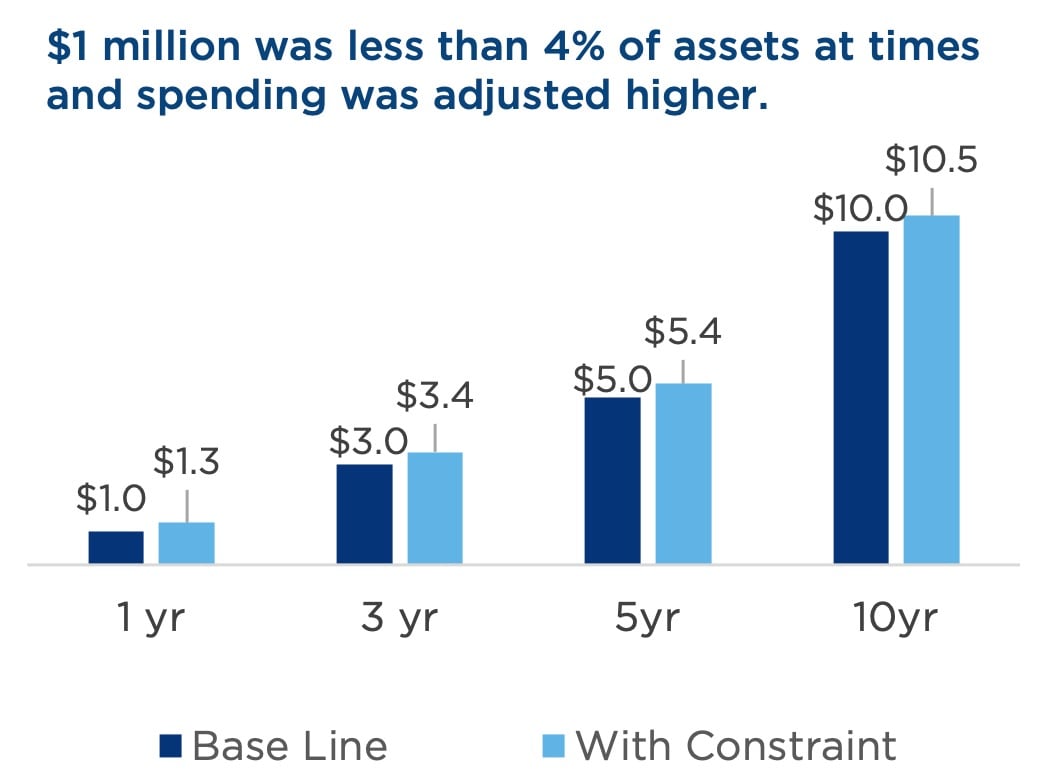

Example A: Spending Floors and Ceilings

An organization may choose a flat dollar spending target, such as $1 million per year, and an additional constraint that restricts the dollar value to a minimum of 4 percent and a maximum of 6 percent of assets. While $1 million is the annual spending goal in this example, if, in a particular year, conditions result in a $1-million spend equaling less than 4 percent of assets, then distributions would be adjusted higher. The inverse would be true for a spending ceiling: If conditions result in $1 million equaling less than 6 percent of assets, then distributions would be adjusted lower.

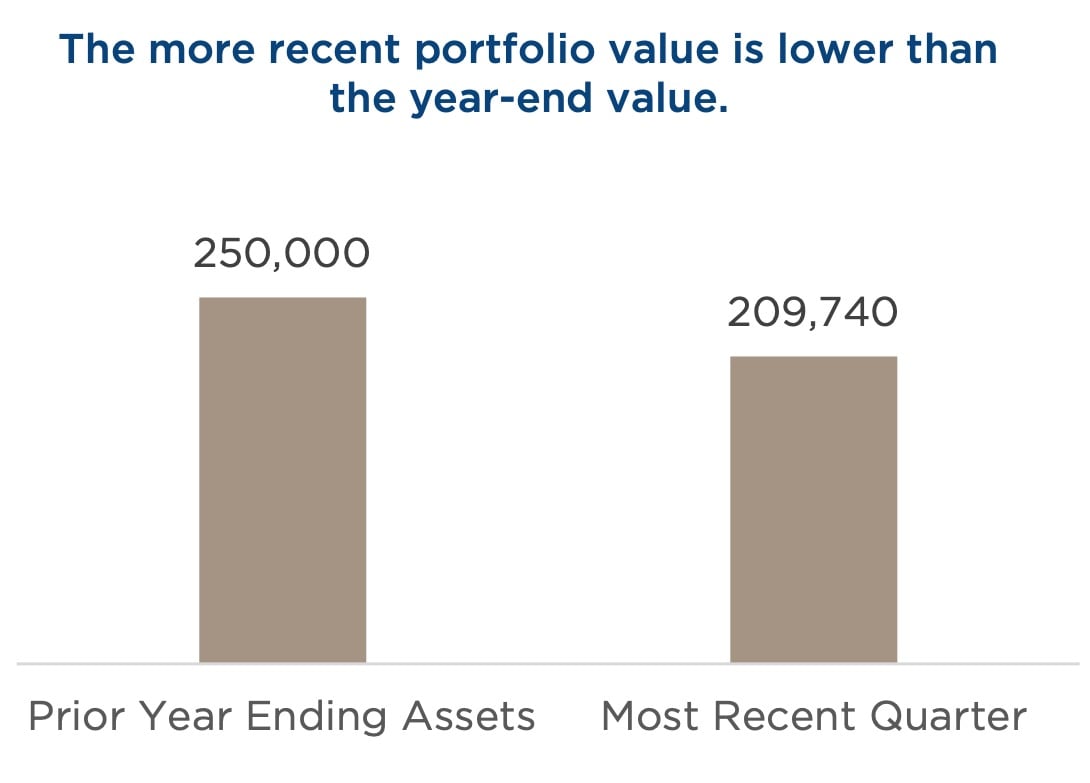

Example B: Portfolio Valuation Date

Another organization may choose a simple 5 percent annual spending policy. Determining the applicable date of market values can impact the sensitivity of spending levels to fast-changing market conditions, Terrell says. For instance, the organization may have targeted spending of $250,000 as of year-end, but the amount would be lowered to $210,000 if an additional rule considers a more recent asset value. The organization may choose to make the inverse true as well, specifying that if asset values on a defined date equal more than $250,000, spending may be raised. This could happen as the result of an unusually large rally or after the receipt of a large gift, for example.

Example C: Market Conditions

Some conditional spending policies may adjust spending levels when market performance meets certain thresholds or when assets rise above—or fall beneath—specific values. Another option is to temporarily halt distributions after a large enough decline in the portfolio, when assets fall below a reserve level. Some organizations will also choose to increase spending over time to address inflation.

When Markets Are Down

“No matter which policies are implemented,” says Verhaeghe, “every organization will have to consider its unique requirements. A private foundation might be subject to IRS rules, while a public foundation might have more flexibility. One organization may rely heavily on an endowment or foundation to cover its operational expenses, and another may have a mission that requires significantly more spending in a tough market.”

This is a common theme. Many endowments and foundations have a greater need for spending when markets are depressed. In fact, for some of these organizations, reducing spending in times of disruption will run contrary to the reason they exist—to support people, institutions, and communities, especially when they need it most.

“It’s not lost on me that telling endowments and foundations to spend less in a difficult economic environment is easy to say and hard to do,” Verhaeghe says. “But this is unlikely to be the only time that markets are volatile or down.”

His advice: “Stay committed to the mission. But also, as a long-term best practice, the more planning an organization can do, the more likely it is that its team will make good financial decisions, because planning helps create balance between immediate spending needs and long-term spending plans.”

Understanding that the organization will almost certainly face another unusual market makes a clear case both for robust planning and for conditional spending policy design. “With a defined spending policy that is formally documented in the organization’s IPS, decision makers are not simply reacting to portfolio growth or decline,” says Verhaeghe. “They’re making proactive decisions that help protect the organization’s ability to achieve its mission, both now and for the long run.”