Fed Plowing Ahead, in the Dark

The economy, like the growing season, is cyclical. Farmers know when to plant seeds so that crops peak at just the right time. Along the way, they rely on weather forecasts and real-time measurements of soil conditions to fine-tune their use of water and fertilizers. They do this because the stakes are high; the upfront cost to put a crop in the ground is enormous, and a failed harvest would be disastrous.

The Federal Reserve and other global central banks are, likewise, tenders of the global economy. They can adjust monetary policy to provide stimulus when conditions slow down and tighten when growth and inflation overheat, just as farmers can adjust nutrient applications to speed up or slow down crop maturation.

But unlike farmers, the Fed lacks real-time feedback. When it pulls a lever to tighten conditions, the extent of that change will likely not be fully known for six to 18 months. It’s always operating in the dark.

Today, it is widely believed that the Fed acted too late to effectively curb inflation. They didn’t get the seeds in the ground fast enough. Now, they’re making up for lost time through the fastest tightening cycle in the modern era, effectively driving a massive tractor at full speed at midnight. If they move too fast or understeer, they could plow right through a fence and push the economy into a recession.

Third-Quarter Recap

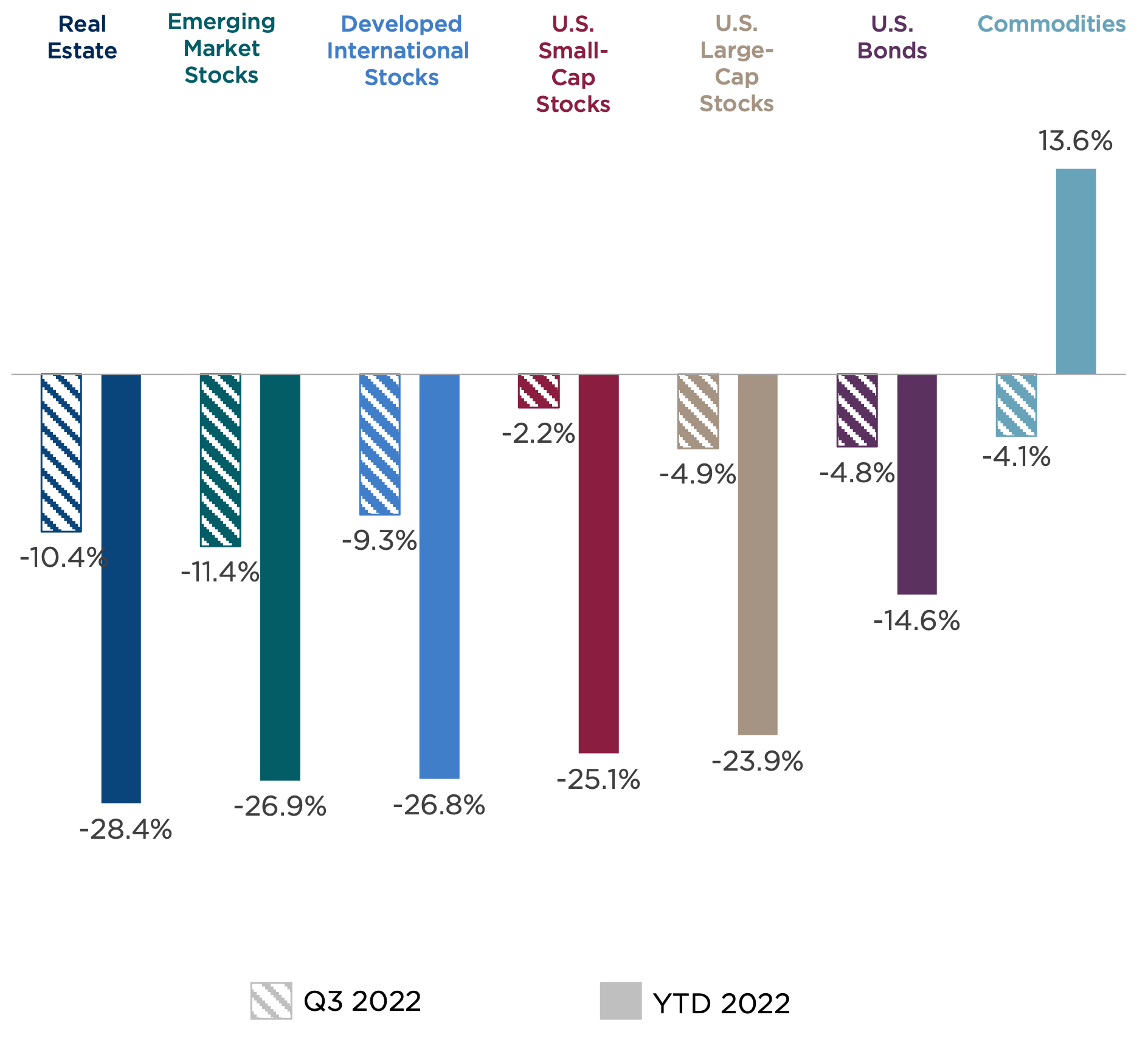

All major asset classes ended the third quarter with losses, ranging from 4.1 percent for commodities to 11.4 percent for emerging markets. It was a mirror image of second-quarter results that showed the same pattern of diversifrustration, leaving even well-diversified investors frustrated.

Figure One: Asset Class Returns (Third Quarter and Year to Date 2022)

Sources: Asset class returns are represented by the following indexes: Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index (U.S. bonds), S&P 500 Index (U.S. large-cap stocks), Russell 2000® (U.S. small-cap stocks), MSCI EAFE Index (international developed market stocks), MSCI Emerging Market Index (emerging market stocks), Dow Jones U.S. Real Estate Index (real estate), and Bloomberg Commodity Index (commodities).

U.S. equities delivered a wild ride during the quarter, with large-cap stocks rising by more than 10 percent by mid-quarter before plunging into negative territory, resulting in a 4.9 percent loss for the quarter. Small-cap stocks fared modestly better than their large-cap counterparts, and growth stocks outperformed value stocks for the quarter.

Outside the U.S., European stocks faced further declines amid the ongoing war in Ukraine and resulting energy shortages, which grew worse after simultaneous leaks were discovered on two major gas pipelines. Led by rising energy costs, Eurozone price inflation reached double-digit levels in September. Within emerging markets, the growing prospects for slowing global trade, continuing struggles in China, and an exceptionally strong U.S. dollar created significant headwinds.

For bond investors, this no-good, very-bad year grew worse in the third quarter as core U.S. bonds declined by another 4.8 percent, bring their year-to-date return to negative 14.6 percent. This represents the worst-ever return at this time of the year, eclipsing the prior largest drawdown by a wide margin, as seen in Figure Two. One reason for this outsized reaction is that starting rates were so low; if you start a rate-hike cycle with a 5 to 7 percent yield, the income stream helps offset the price declines caused by rising rates. This year, we began with a 10-year Treasury yield of just 1.5 percent, leaving little yield cushion to offset price declines. Rising interest rates and concerns about potential recession also added to 2022 difficulties for public real estate.

Although commodities also declined 4.1 percent for the quarter, it remains the only major asset class with positive returns (13.6 percent) on a year-to-date basis.

Figure Two: Core Bond Prices on Pace for Historic Losses (1976-2022)

Sources: Bloomberg, CAPTRUST Research; Data as of 9.23.2022

While these returns will leave any investor feeling glum, there is a silver lining. Existing bond prices fell as their yields rose. This means that long-term investors can now pick up bonds with the potential to provide meaningful income. Even 10-year Treasurys are now paying yields approaching 4 percent: their highest level in more than a dozen years.

The Pest in the Field: Inflation

When markets are volatile, it’s important to attempt to cut through the noise and focus on the main event. Currently, all eyes are fixed on inflation and the Fed’s attempt to control it.

Consumer Price Index (CPI) data for the month of September all but cemented the Fed’s course toward another outsized 0.75 percent rate hike next month. CPI increased by 8.2 percent from a year earlier, which was a slight decline from the August reading. However, core CPI, which excludes some of the more volatile categories such as food and energy, which are less affected by monetary policy, rose to 6.6 percent from a year ago, the highest level in four decades.

Another issue with the inflation we’re experiencing today is its source. Some inflation can be classified as demand-pull inflation, which happens when strong consumer demand outpaces supply, causing prices to rise. This type of inflation was felt during and after the pandemic, as consumers raced to buy goods during lockdown, then rushed to consume services as the economy reopened. Demand-pull inflation tends to be reactive to Fed policy moves.

In contrast, cost-push inflation occurs when supplier costs increase, whether through rising input and energy prices, production bottlenecks, supply-chain disruptions, or higher wages. These issues are less affected by the Fed’s toolkit and may require other forms of policy change to move the needle.

Laser-Focused Fed

The goal of any central bank is to establish economic confidence by keeping inflation low and stable while supporting an environment for a healthy labor market and growth conditions.

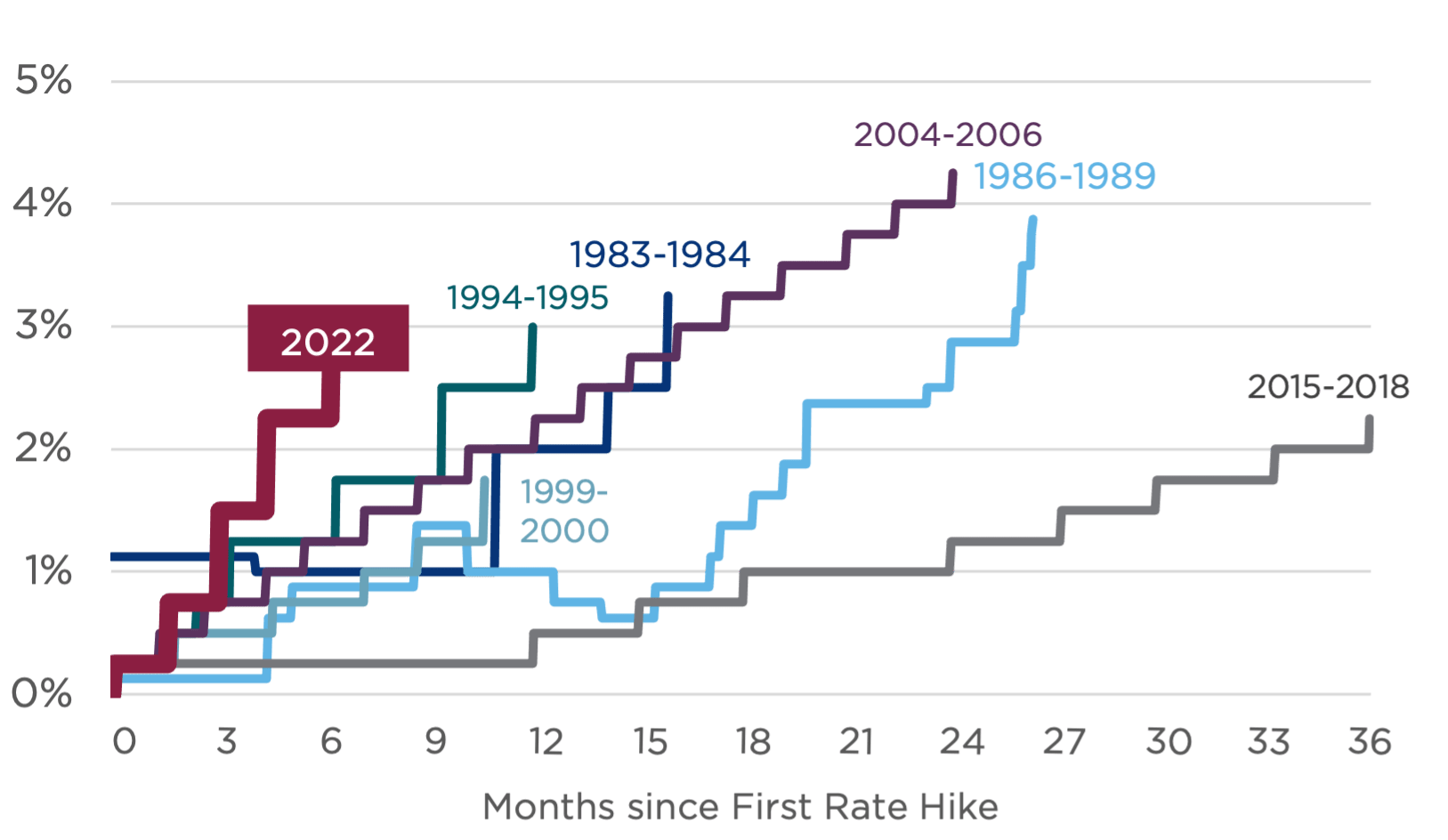

However, the high and rising level of inflation has sharply narrowed the Fed’s focus. High inflation that risks becoming entrenched has prompted the Fed to act far more swiftly than ever before, as the steep incline in Figure Three shows. Continued strength in the labor market provides room for this hawkish stance. The Fed seems resolved to tighten until inflation comes under control, even if it causes pain elsewhere in the economy.

Figure Three: The Fed’s Historical Tightening Pace

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, CAPTRUST Research

How did the Fed get itself into this position? As stated, Fed policy acts with a lag. It’s like trying to park a truck with the steering wheel and brakes on a 60-second delay. It seems the Fed temporarily forgot this fact in early 2021 as inflation began to accelerate but was explained away as temporary or transitory. Yet, even as it became clear late last year that inflation was a growing problem, the Fed did not raise rates until March.

The Fed’s objective is to engineer a soft landing—containing inflation without triggering a recession. But historically, this has been difficult to achieve, notwithstanding the added complexity facing the economy today. Over the past 60 years, throughout the course of eight recessions, we have seen only one true soft landing, suggesting that the odds of a Goldilocks outcome are poor.1

The last nine months are a stark reminder of what life is like when we have elevated inflation and an aggressive Federal Reserve. Markets especially dislike such policy uncertainty because it is not driven by fundamental or technical factors that can be analyzed but, rather, by the decisions of a small group of people and their various spreadsheet models, both of which are opaque.

Recession Complexion

Assuming that a soft landing isn’t achieved—a hope that’s growing dimmer by the day if you trust the continued and worsening inversion of the yield curve—then the next question on investors’ and business leaders’ minds is what the subsequent recession would look like.

Despite the significant market reaction so far this year, there are several positive signs that provide hope that even if the economy slips into recession, it could be a shallow and less painful one. Such factors include:

1. The Labor Market

One fact that has bolstered the Fed’s aggressive policy this year is the continued tightness within the labor market. There are still approximately two job openings for each unemployed worker today. And like any scarce resource, we could see hoarding behavior for talent within companies, which could prevent the mass layoffs that often accompany a recession.

2. Housing

With declining home sales and mortgage rates that have more than doubled from 3.2 to 6.9 percent this year, we expect to see weakness in the housing market. However, mortgage balances have increased only modestly over the past 20 years, while home equity has soared. This equity cushion should help keep a housing correction from becoming a crisis.

3. Strong Balance Sheets

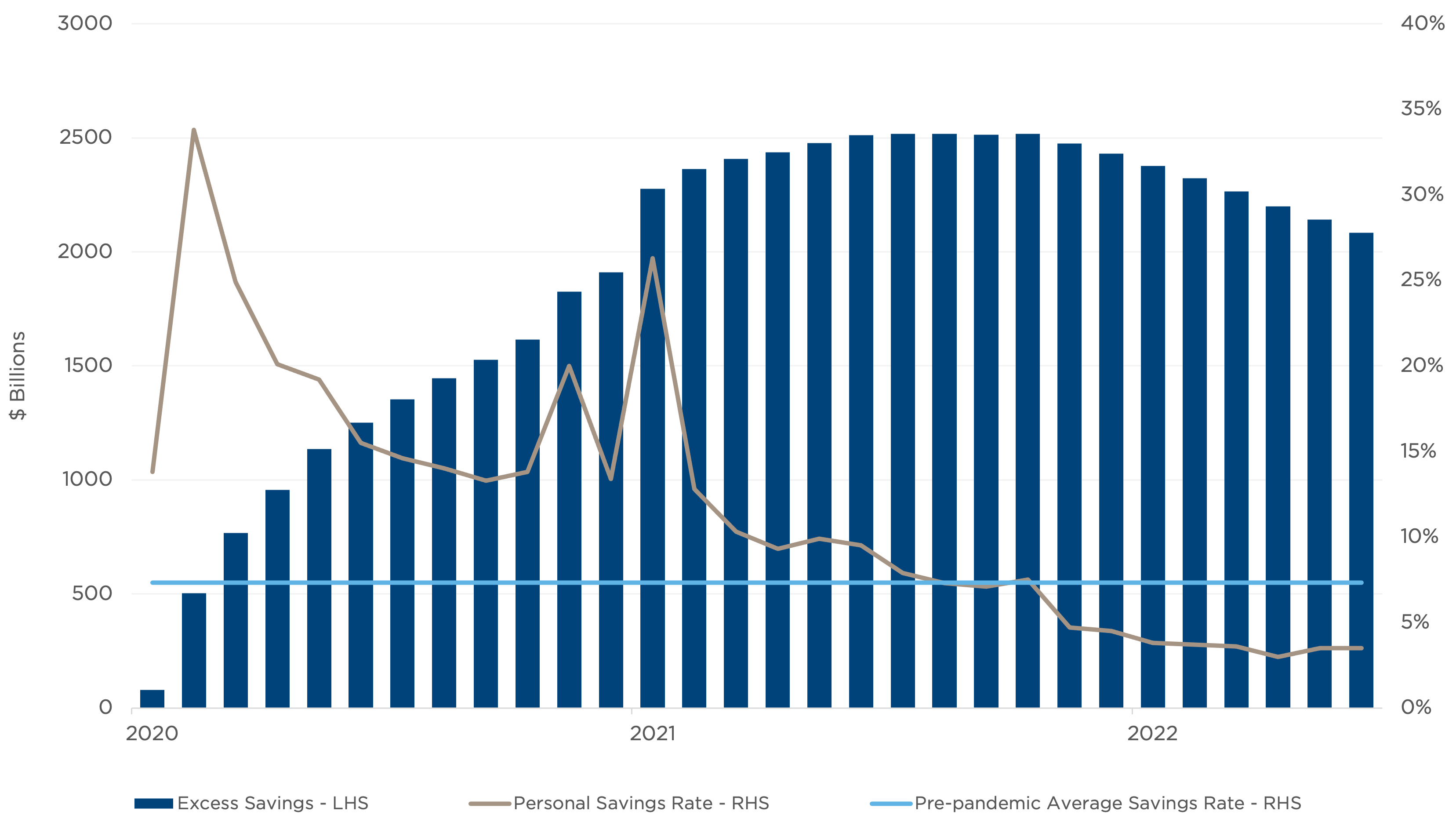

Despite low levels of consumer confidence, consumer spending has remained robust. This is due in part to strong household balance sheets that maintain a $2 trillion surplus of excess savings. However, spending began to slow in August, and the personal savings rate and levels of revolving credit have both deteriorated, suggesting that households are dipping into savings and tapping into home equity and credit cards to maintain spending or compensate for rising prices. Figure Four shows the volume of excess savings and the personal savings rate since the pandemic began in March 2020.

Figure Four: U.S. Excess Savings

On the flip side, while these sources of strength suggest a mild recession, it very well could be a longer recession as well. Typically, the Fed can turn on a dime at the first sign of recession to help soften the blow with lower borrowing costs. But this time, in an inflation-driven recession, it likely won’t have this luxury.

While the Fed could take other actions to ease financial conditions—such as suspending its quantitative tightening program—the prospect for rapid rate cuts is slim. In short, the length and severity of the recession will be driven by how high and sticky inflation proves to be relative to the Fed’s pain tolerance as the economy slows and unemployment rises.

What Might Happen

We believe the chances of a recession next year have increased to greater than 50 percent. However, stocks typically reach their bottom before the onset of a recession (or in hindsight, when it is declared). Much of the pain has already been priced in.

As we’ve said many times, the economy isn’t the market, and the market isn’t the economy.

The outlook for stocks remains clouded by uncertainty, which usually translates into volatility. Stock prices have declined significantly this year, while profit margins have remained elevated. As a result, measures of valuation, such as the price-to-earnings ratio, have fallen from well above their long-term average to below average.

On one hand, lower valuations improve the outlook for long-term stock investors, particularly when combined with depressed investor sentiment. But so far, we have witnessed a bear market in valuations but not earnings. As the risk of recession grows, stocks could come under further pressure through declining fundamentals while an exceptionally strong U.S. dollar dilutes the overseas earnings of U.S. companies.

Amid this global uncertainty, the competitiveness of the U.S. economy has never been more visible. While we may not be able to escape a recession, our economy is more resilient than those of much of the rest of the world, benefitting from abundant natural resources, a well-developed infrastructure, a stable financial system, and high levels of productivity.

Cautious Optimism

There is a Chinese proverb that explains, “The corn is not choked by the weeds but by the negligence of the farmer.” As large, dynamic, and resilient as the U.S. economy may be, it cannot escape trouble caused by the policy decisions—or mistakes—of a small group of people. We are witnessing this reality today within the UK, where policymakers appear to be fighting themselves with fiscal stimulus and tax cuts amid high inflation that the Bank of England is trying to control.

Given the high degree of uncertainty facing the markets today, we are maintaining our cautious outlook. At the same time, we are watching for signs that the worst is behind us. Until then, in a world with an expanding range of potential outcomes, the best defense is, as always, a well-diversified portfolio aligned with your personal risk tolerance, time horizon, and financial goals. The signs are pointing toward a bountiful crop, even though we can’t predict the weather for the rest of the year.

1Source: PSC Research, March 2022