Navigating the Number Jumble: A 403(b), 401(k), and 457(b) Comparison

Over the years, through regulation changes and plan design mandates, the three predominant types of defined contribution retirement plans—403(b), 401(k), and 457(b)—have grown more similar.

However, a number of key distinctions remain.

Understanding the nuances between these plan types can be daunting. But for those plan sponsors with choice, like private tax-exempt 501(c)(3) charitable organizations, digging into the differences may help clarify which plan type, or combination of plan types, to offer. Below are the most significant distinctions among the three types of plans, in order of importance.

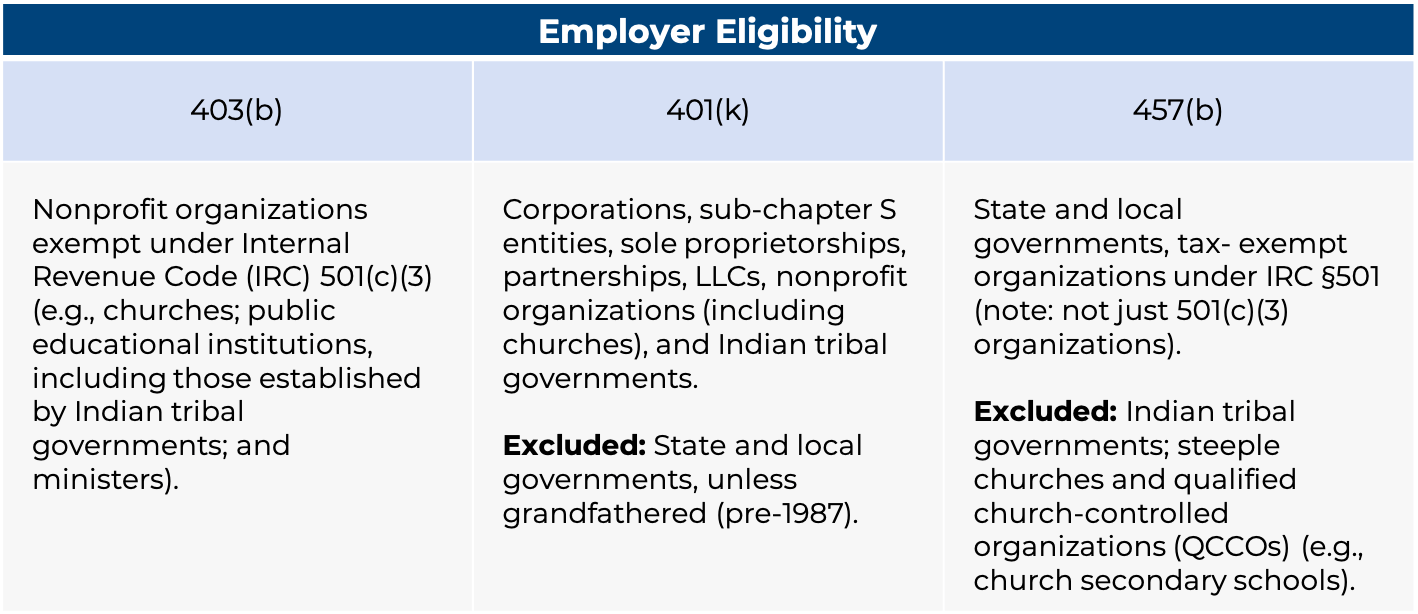

Employer Eligibility

One of the primary differences is the type of employer eligible to sponsor a particular type of plan. For example, state and local governments, public colleges, and universities may not offer a 401(k) plan unless their state maintained a 401(k) plan that was established before 1987. Likewise, private tax- exempt organizations that are not 501(c)(3) educational or charitable organizations, such as associations and clubs, may not maintain a 403(b) plan. And while public and private colleges and universities may maintain a 457(b) plan, the rules governing these plans vary widely depending on employer type.

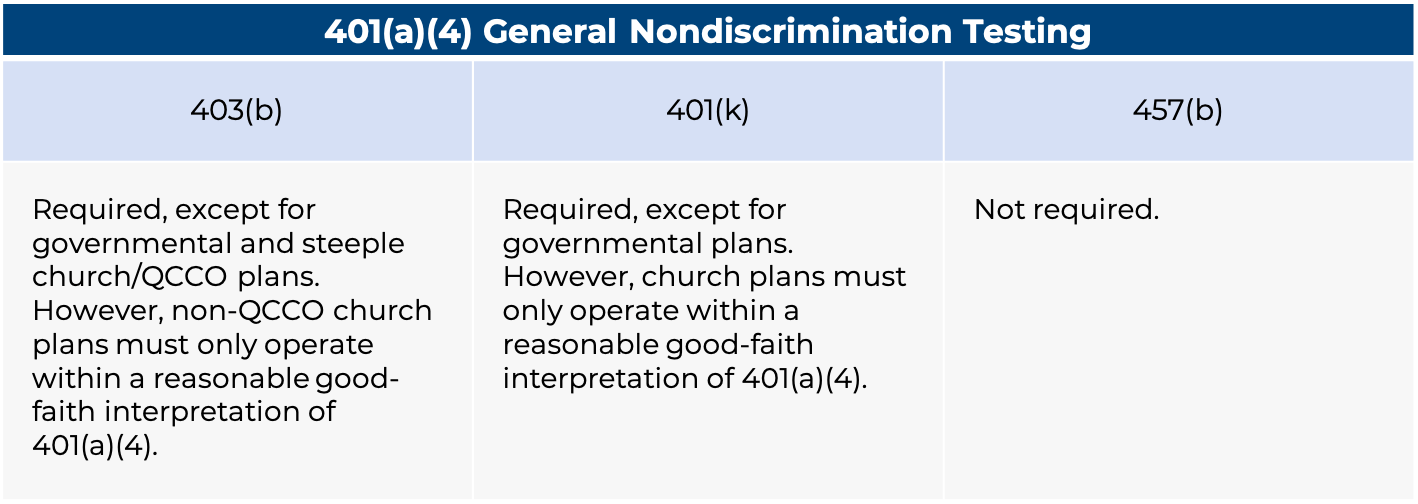

Nondiscrimination Testing

Nondiscrimination testing in 401(k) plans requires that highly compensated employees (HCEs), defined in 2023 as those earning more than $135,000 in 2022, stay within a specific contribution rate determined by the average contribution rate of non-highly compensated employees (NHCEs).

This testing is one of the key reasons why many private tax-exempt 501(c)(3) charitable entities, such as hospitals and colleges and universities, continue to use 403(b) plans instead of 401(k) plans. For 403(b) plans, it is unnecessary to test salary-deferred employee contributions. As a result, these HCEs have no additional limitations imposed on their ability to save other than the overall IRS 402(g) restrictions.

For example, in a typical private 501(c)(3) tax-exempt organization, unmatched elective deferrals for NHCEs average 2 percent (this average includes individuals not deferring anything). At this level, HCEs in a 401(k) plan are limited to approximately 5 percent of pay rather than the 2023 IRS limit of 100 percent of pay up to $22,500 per year (or $30,000 if age 50 or older). Thus, these higher- compensated plan participants face significantly restricted deferral limits, which are otherwise moot in a 403(b) plan.

A 457(b) plan presents the opposite problem for private tax-exempt entities. A 457(b) plan, sponsored by a private college or university that is not a 414(e) religious organization, is of limited use, since these top-hat plans are required to discriminate in favor of HCEs. Thus, they do not serve as the primary retirement plan for these organizations but are instead used as a supplemental plan for select groups of management employees.

An advantage of 457(b) plans is that employer contributions of any type can be discriminatory, whereas in 401(k) and 403(b) plans, employer contributions must be tested for nondiscrimination (with the exception of certain organization types exempt from testing).

Nondiscrimination testing is not a consideration for certain types of organizations. For example, governmental plans, such as those sponsored by public universities, are not subject to nondiscrimination testing, and 457(b) plans can be offered to all employees at these organizations.

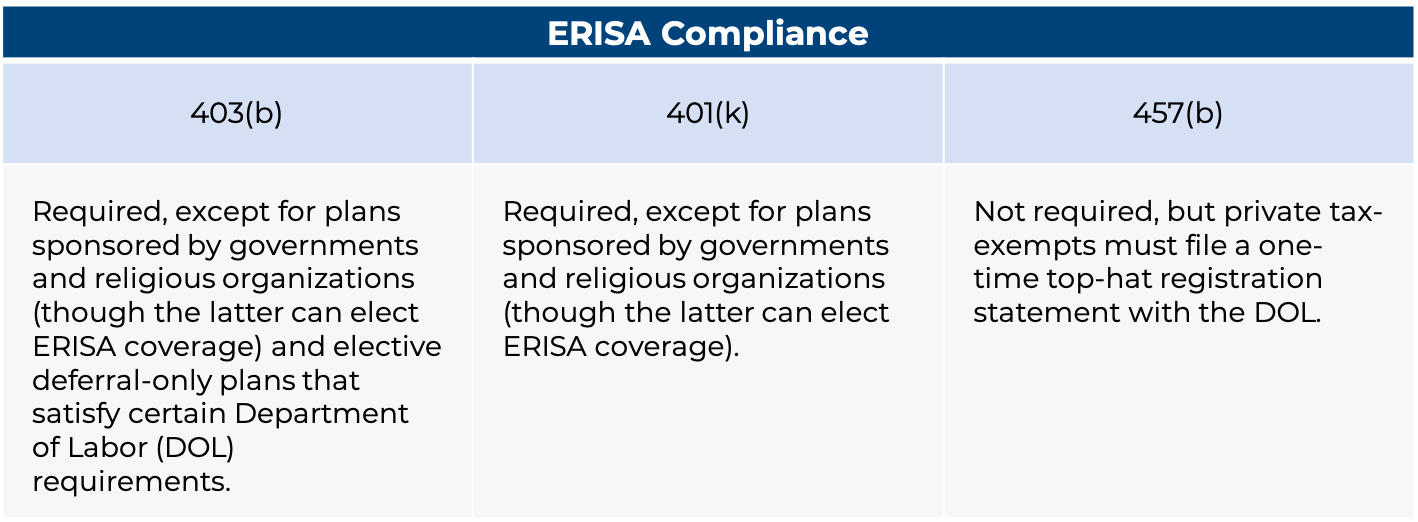

ERISA Coverage

Another defining feature of 403(b) and 457(b) plans is that elective deferral-only plans of private 501(c)(3) charitable organizations are generally exempt from the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA). While this is uncommon among 403(b) plans, ERISA exemptions are not a possibility for 401(k) plans. Note, however, that public entities and churches are not subject to ERISA, regardless of plan type; churches may elect ERISA coverage, but it is rare.

Private education employer 457(b) plans are technically subject to ERISA, but a single top-hat filing with the government essentially exempts the plan from ERISA requirements.

For 403(b) plans to be exempt, plan sponsors must only permit elective deferrals (no employer contributions) and satisfy several other requirements that generally restrict employer involvement in the plan. This exemption means that for these plans, no summary plan descriptions are required, no annual Form 5500s or summary annual reports are required to be filed and distributed, and an annual audit is unnecessary—the audit alone can be a significant cost factor as well as an administrative burden. While the 403(b) exemption is not as attractive as it once was due to new regulatory requirements, the ERISA exemption remains an important option for 403(b) and 457(b) plans, one that is unavailable in the 401(k) world.

Universal Availability

The universal availability requirement is unique to 403(b) plans. Universal availability requires that all employees, with limited exceptions, be permitted to make elective deferrals from the date of hire. This contrasts with 401(k) plans, for which eligibility to make elective deferrals can be restricted, subject to nondiscrimination testing requirements. It is important to note that the recently enacted Setting Every Community Up for Retirement Enhancement (SECURE) Act now requires the inclusion of certain part- time employees in these 401(k) plans.

Public 457(b) plans have no eligibility requirements, meaning that plan sponsors can allow all or any employees of their choosing to participate. As previously noted, private tax-exempt 457(b) plans can only permit select management and HCEs to participate. Additionally, independent contractors are permitted to participate in 457(b) plans, but not in 401(k) or 403(b) plans.

Contribution Limits

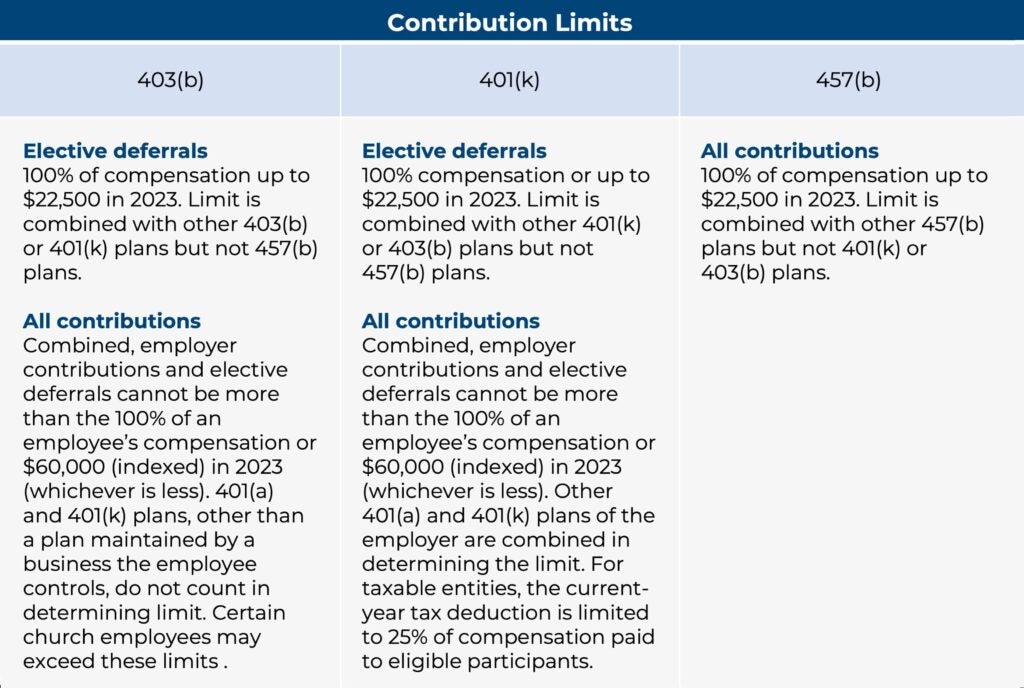

While elective deferral limits to all three plan types are $22,500 in 2023, there are some other important contribution limit distinctions. In 457(b) plans, the limit on combined elective deferral and employer contributions is the same as the elective deferral limit ($22,500). In both 401(k) and 403(b) plans, the combined elective deferral, and employer contribution limit is significantly larger—up to $66,000 in 2023, depending on compensation.

While the combined 457(b) limits are lower, the 457(b) elective deferral limit is not offset by 401(k) or 403(b) deferrals. Thus, the maximum deferral limit of $22,500 may be contributed to a 457(b) plan, regardless of whether any deferrals or employer contributions have been made to a 403(b) or 401(k) plan. For organizations offering a combination of these plans, this presents an opportunity for a participant to contribute to both.

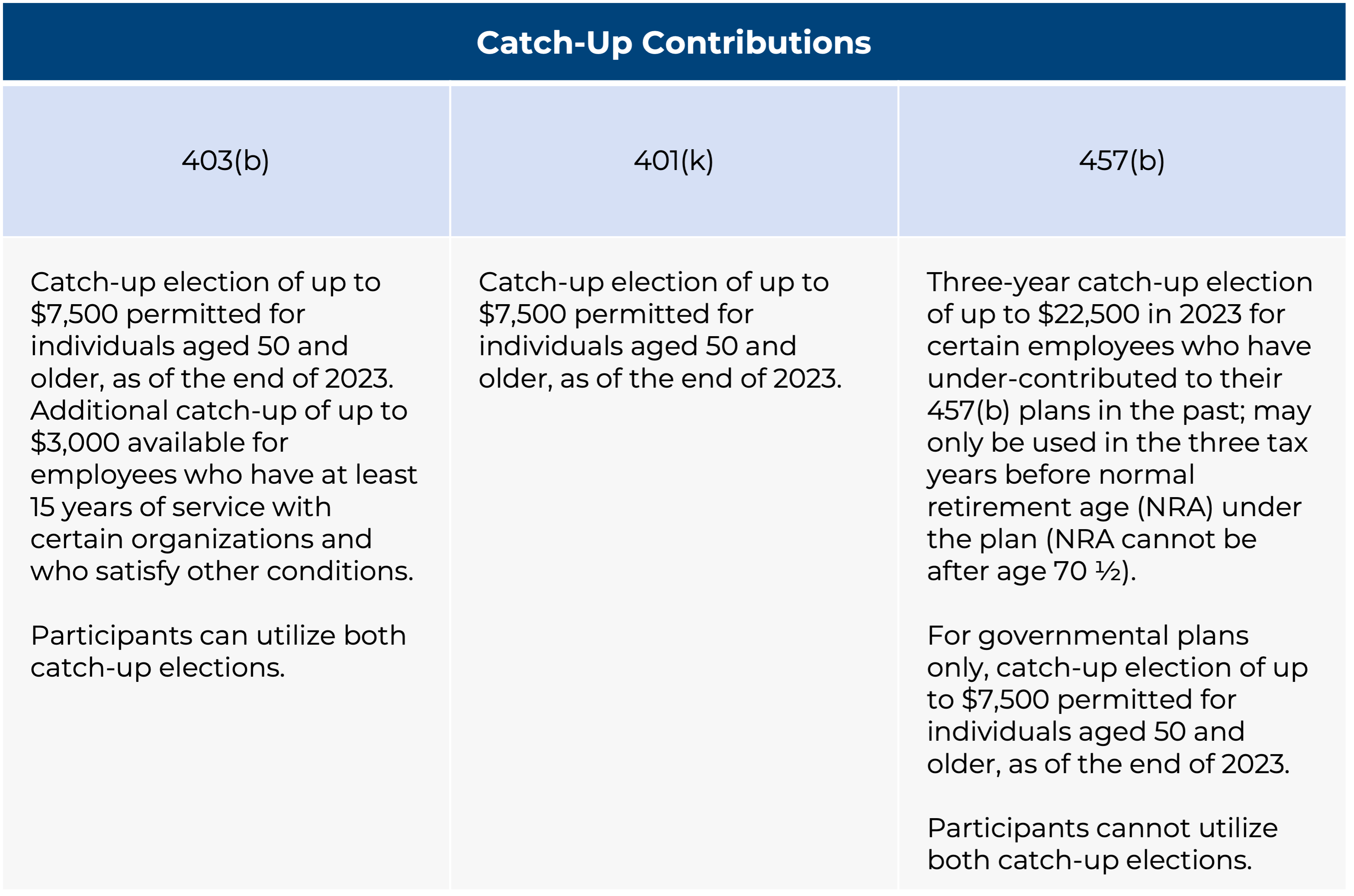

Special elections allow additional elective deferrals based on certain factors. The age 50 catch-up election, which expands the $22,500 limit in 2023 to $30,000, is available in 403(b), 401(k), and public 457(b) plans but is unavailable for 457(b) plans of private tax-exempt organizations. Unique to 403(b) plans is the 15-year catch-up election, which allows a plan to permit employees who have 15 or more years of service and who satisfy additional requirements to defer up to an additional $3,000 beyond the 402(g) limit of $22,500 ($30,000 if age 50 or older) in 2023. However, this election can be complicated to calculate. The 457(b) election permits those in their final three years of employment prior to retirement to defer up to an additional $22,500 in 2023.

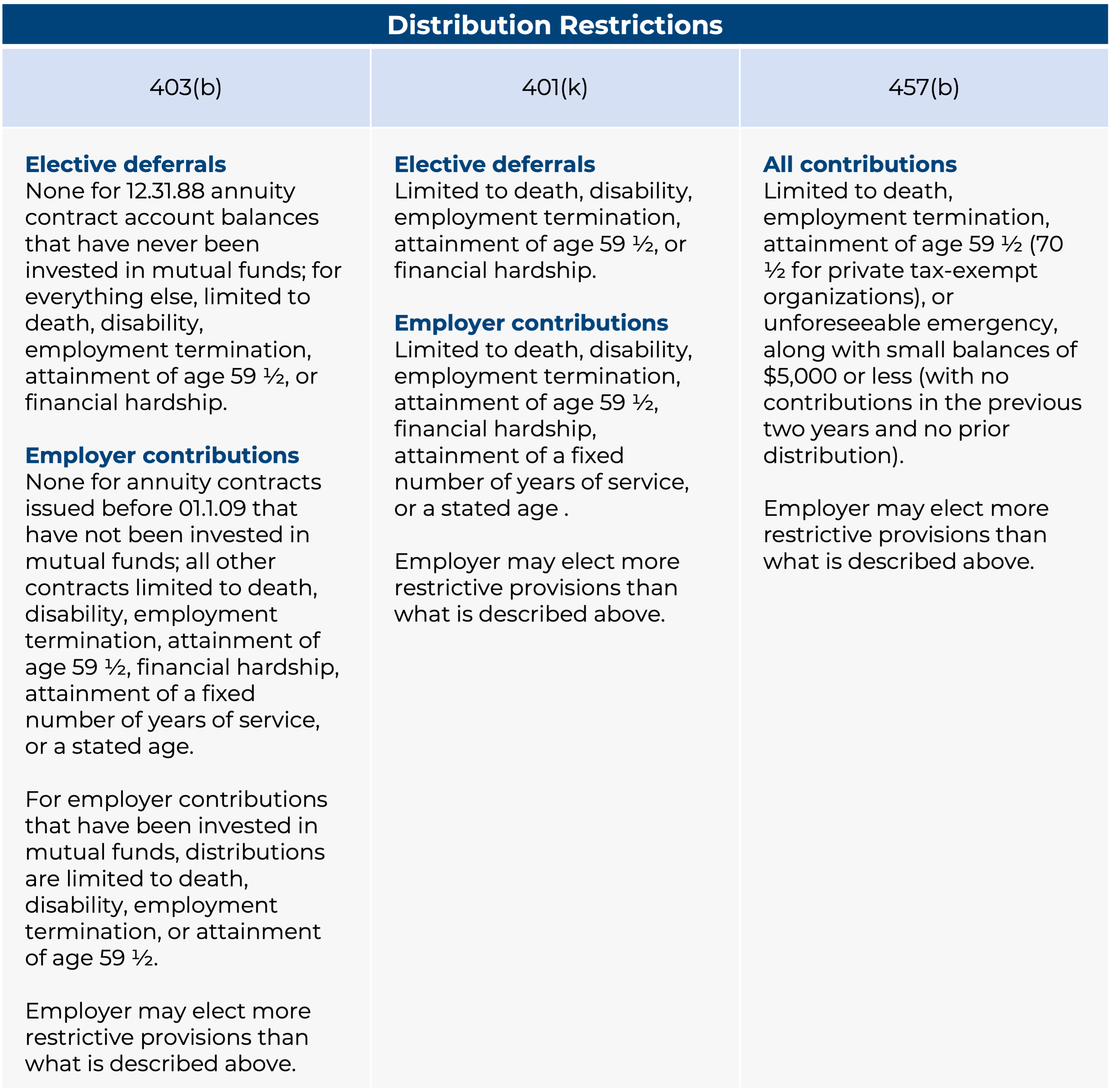

Distributions

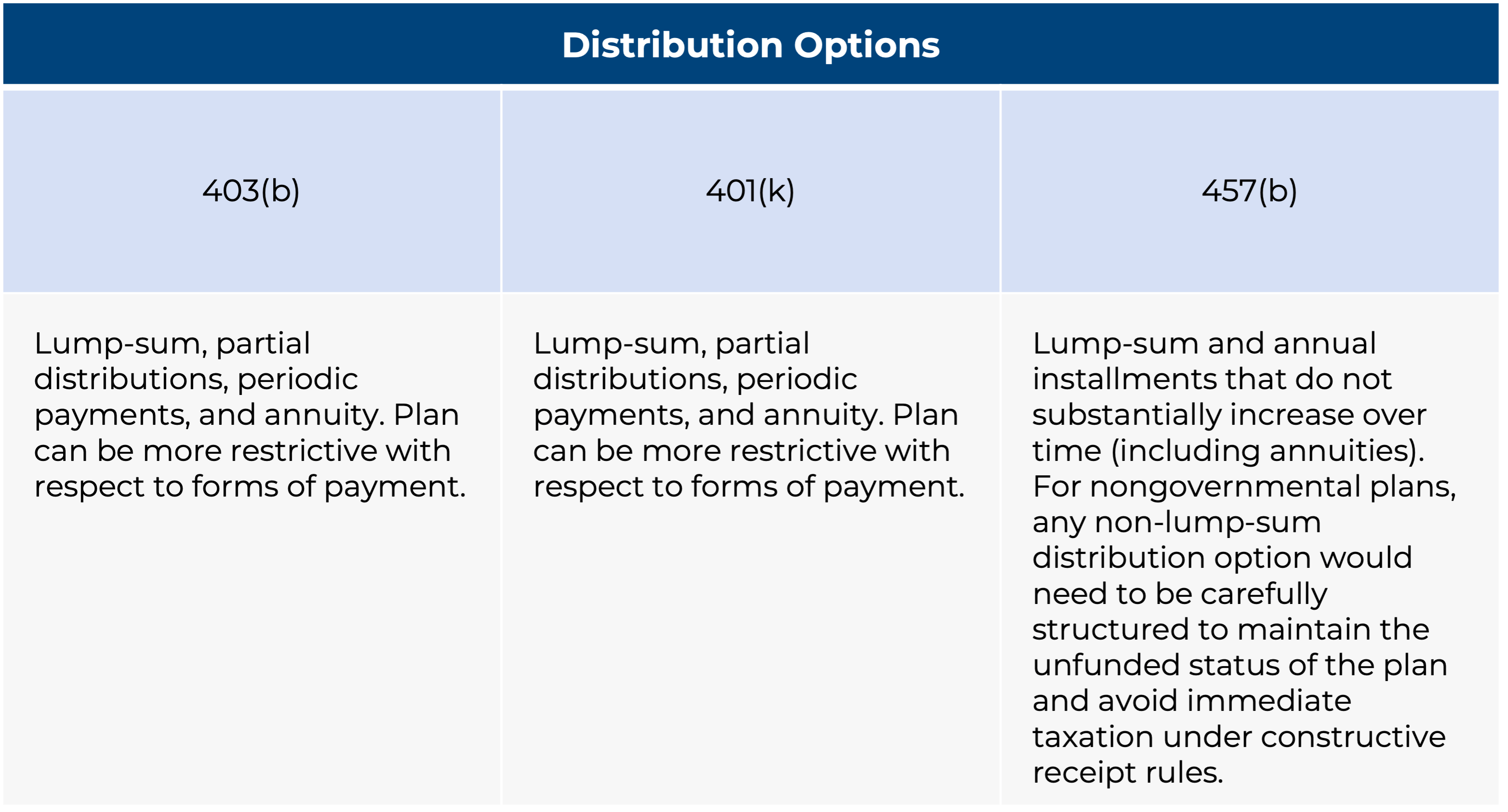

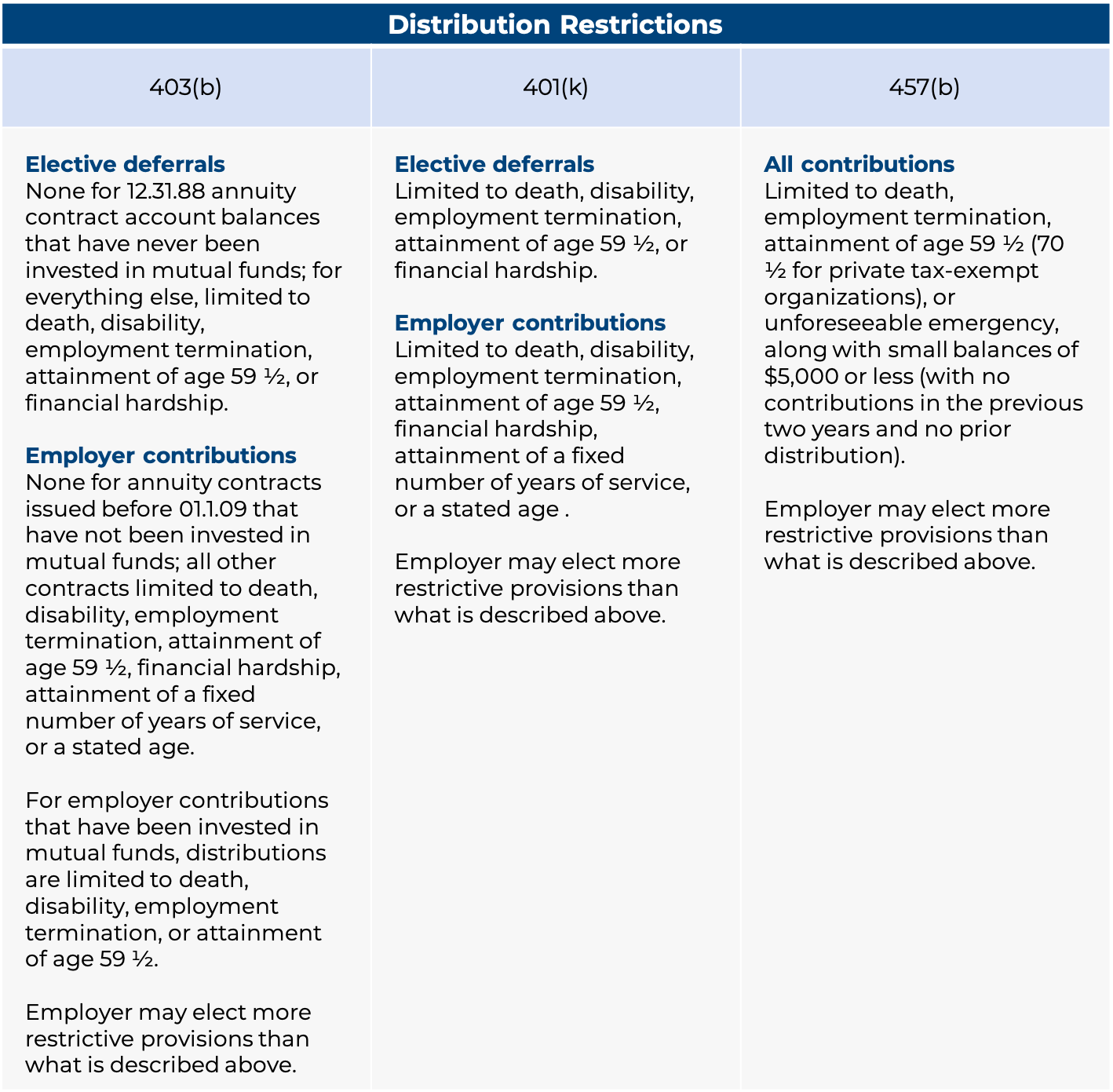

The 403(b) and 401(k) plans generally mirror each other in terms of distribution restrictions. For example, elective deferrals may not be withdrawn in either plan type until the attainment of age 59 1/2, termination of employment, hardship, death, or disability.

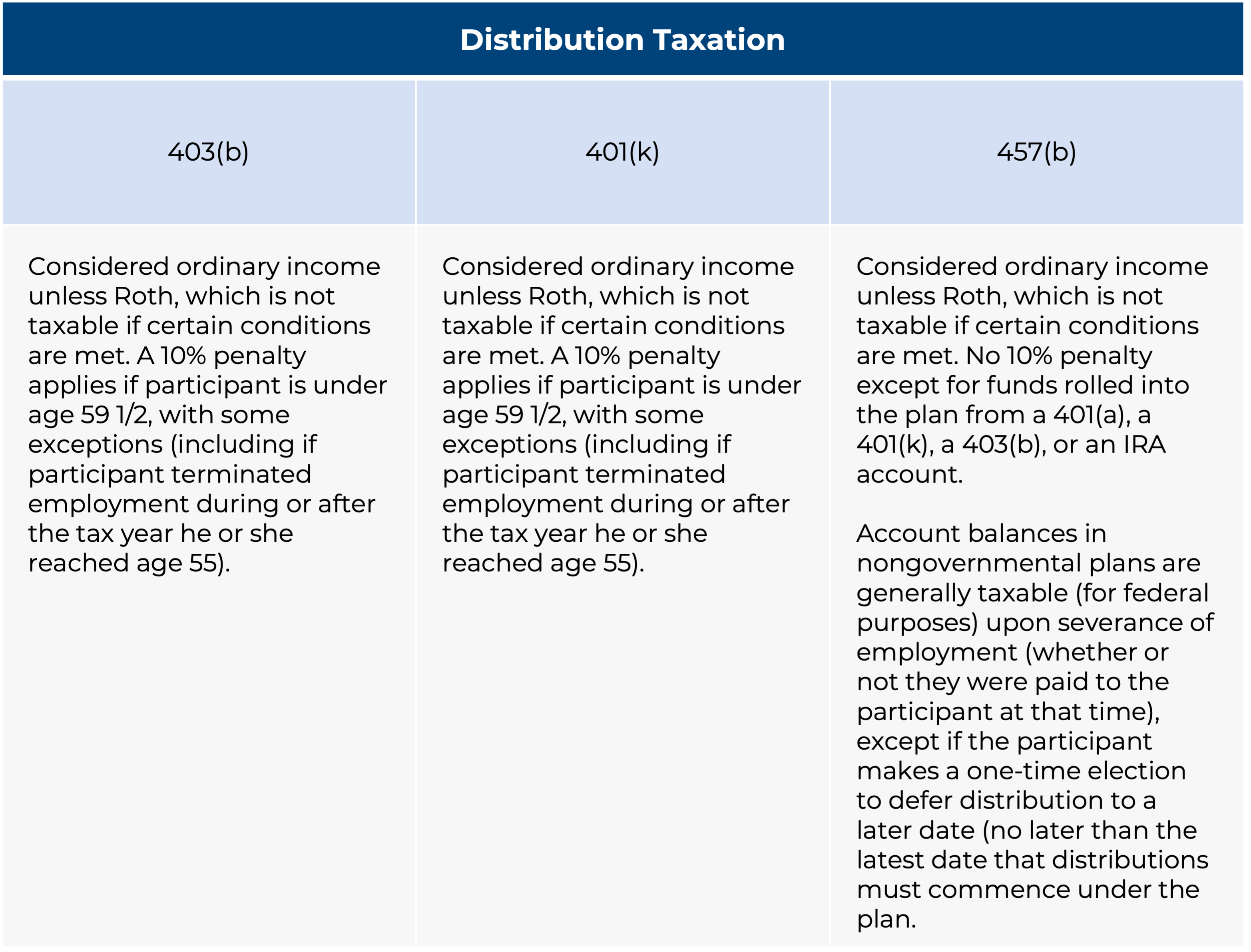

However, 457(b) plans have different restrictions. Contributions may not be withdrawn until severance of employment, attainment of age 59 1/2 (70 1/2 for private tax-exempt organizations), or occurrence of an unforeseeable emergency (different rules than hardship withdrawals). For 457(b) plans at private tax-exempt organizations, there are additional restrictions as to the type of distributions that can be taken, and rollovers are not permitted. One advantage of 457(b) plans, however, is that the 10 percent excise tax for distributions prior to age 59 1/2 does not apply.

Transfers and Exchanges

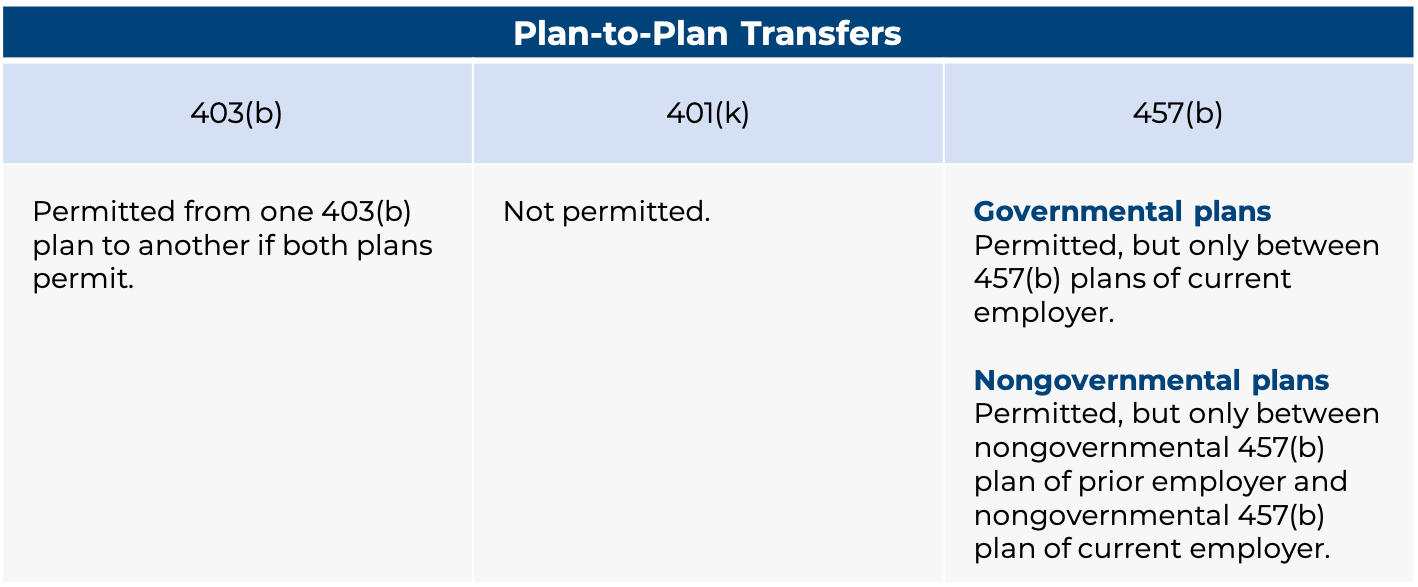

In 401(k) plans, the most common reason for plan-asset movement is employer-directed transfers due to the transition to a new recordkeeper. The situation is similar for 457(b) plans; however, some participants use plan-to-plan transfer provisions for cases in which a rollover is not permitted (i.e., private tax-exempt plans).

For 403(b) plans, there is more flexibility; however, even this has been somewhat restricted by the final 403(b) regulations that became effective a few years ago. Employers may transfer plan assets from one provider to another, but these transfers are more likely to be restricted at the provider contract level than in the case of a 401(k) plan. Plan participants may transfer plan assets in the form of an exchange to any approved provider in a 403(b) plan. Plan-to-plan transfers are also permitted, though employees often opt for a rollover instead.

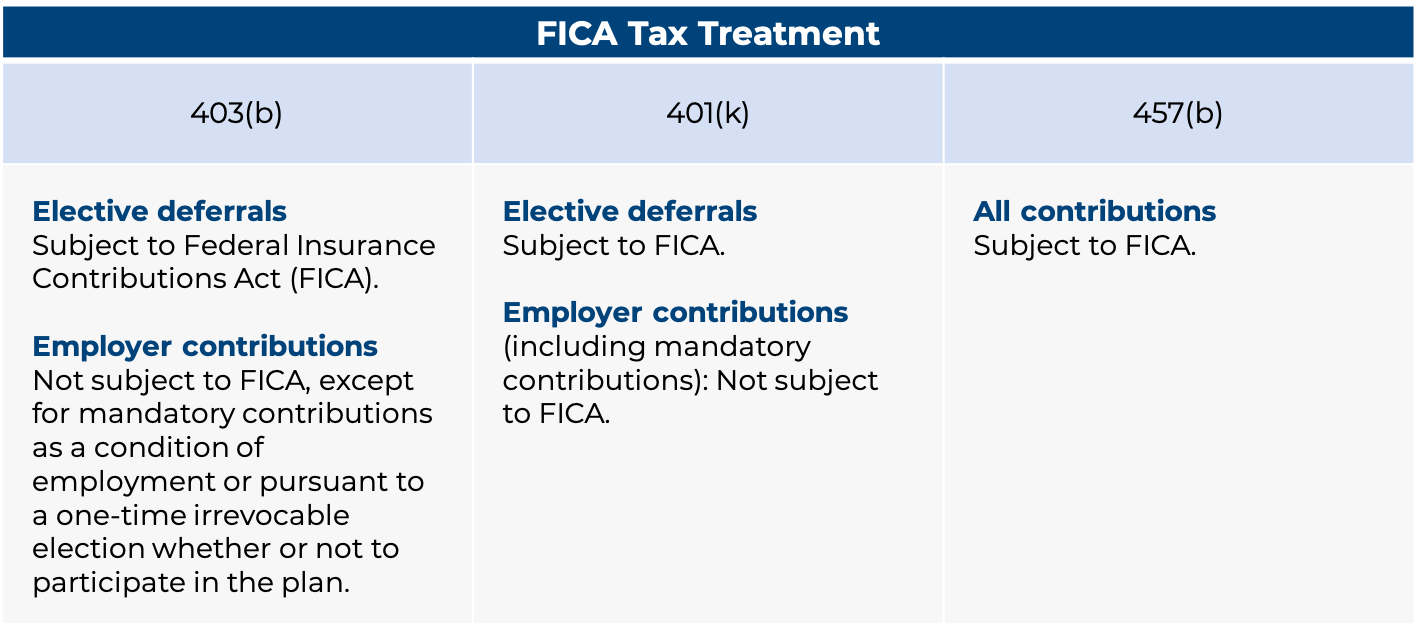

Payroll Taxes

Contributions from employers with 401(k) and 403(b) plans are generally not subject to payroll taxes, such as FICA or Medicare. Since 457(b) plans are deferred compensation plans rather than retirement plans, employer contributions are treated as compensation that is subject to payroll taxes.

Provider Availability

A myriad of recordkeepers service 401(k) plans. Meanwhile, 403(b) and 457(b) plan assets are concentrated among a smaller selection of vendors. While this relative lack of competition can affect pricing and marketplace advancements for larger plans, 401(k), 403(b), and 457(b) product and service offerings are often comparable. While it is not uncommon for multiple recordkeepers to be offered within a 403(b) plan, it is less frequent in 457(b) plans and rare in 401(k) plans.

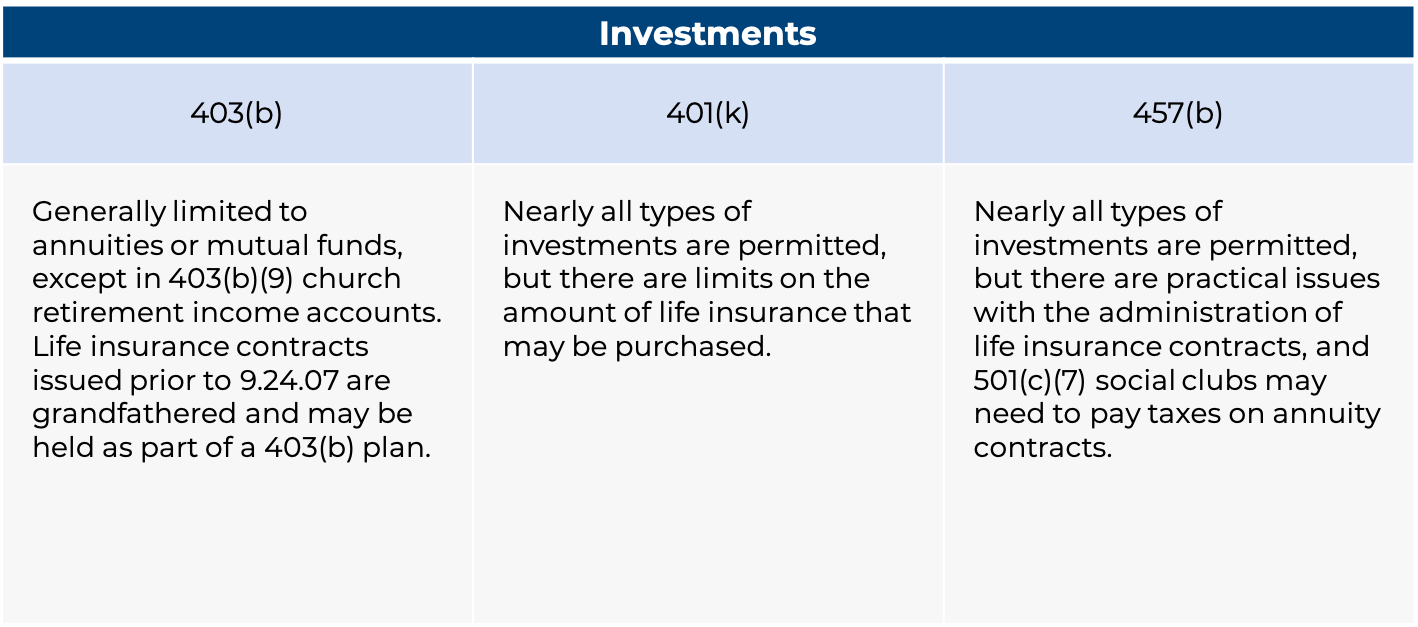

Investments

Another important distinction for 403(b) plans is their limitation in terms of the investment types that can be offered. In these plans, investment types are limited to 403(b)(1) fixed and variable annuities and 403(b)(7) custodial accounts (known more commonly as mutual funds). Investments that are permitted in 401(k) and 457(b) plans, like individual securities, are prohibited in 403(b) plans. It should also be noted that some 457(b) plans are subject to investment-type restrictions by law.

Providing a competitive retirement plan benefit is often an important component of an organization’s recruitment and retention efforts. Understanding the availability, benefits, and limitations of the different plan types can help plan sponsors craft and maintain the most impactful retirement plan offering.

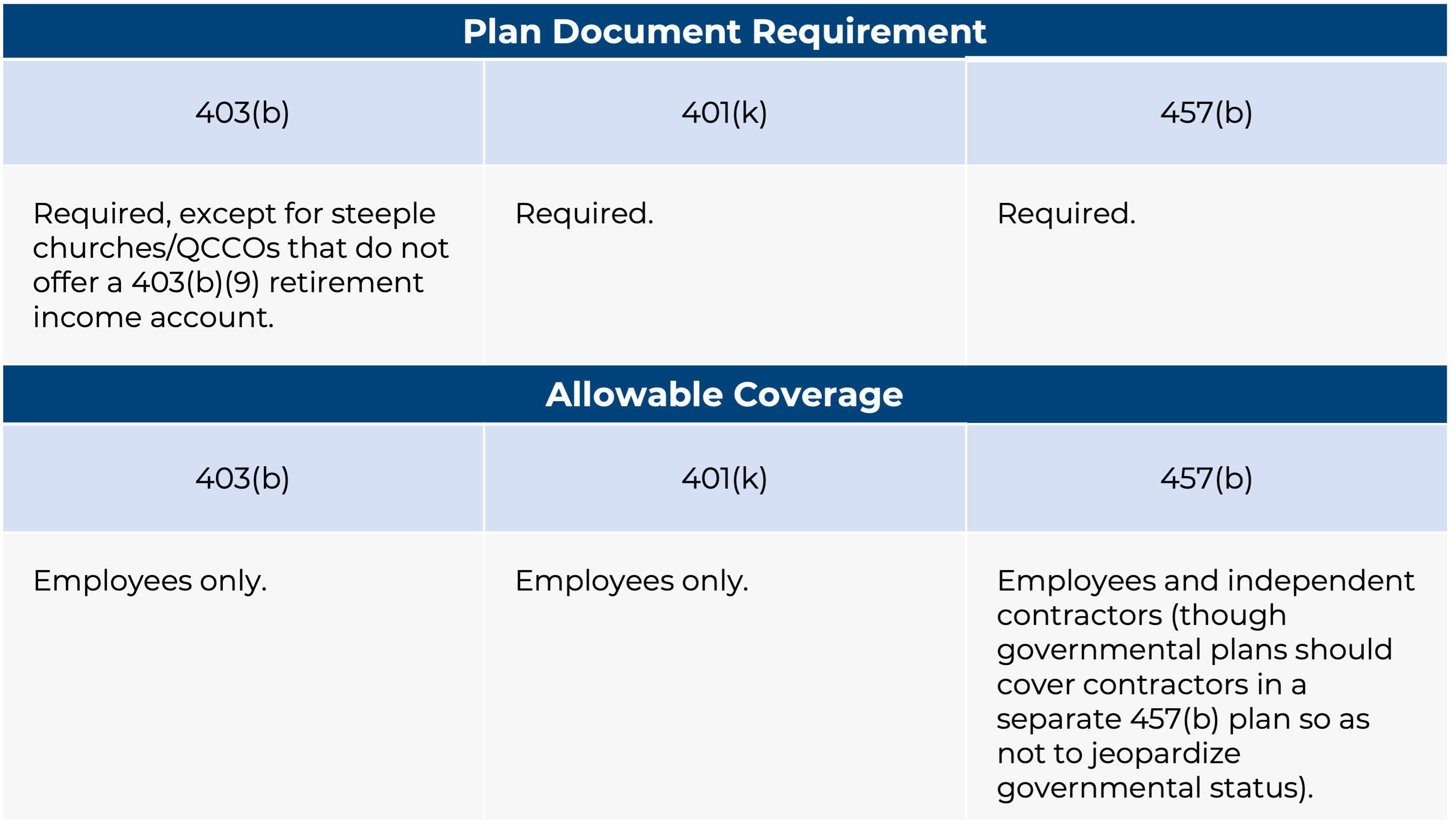

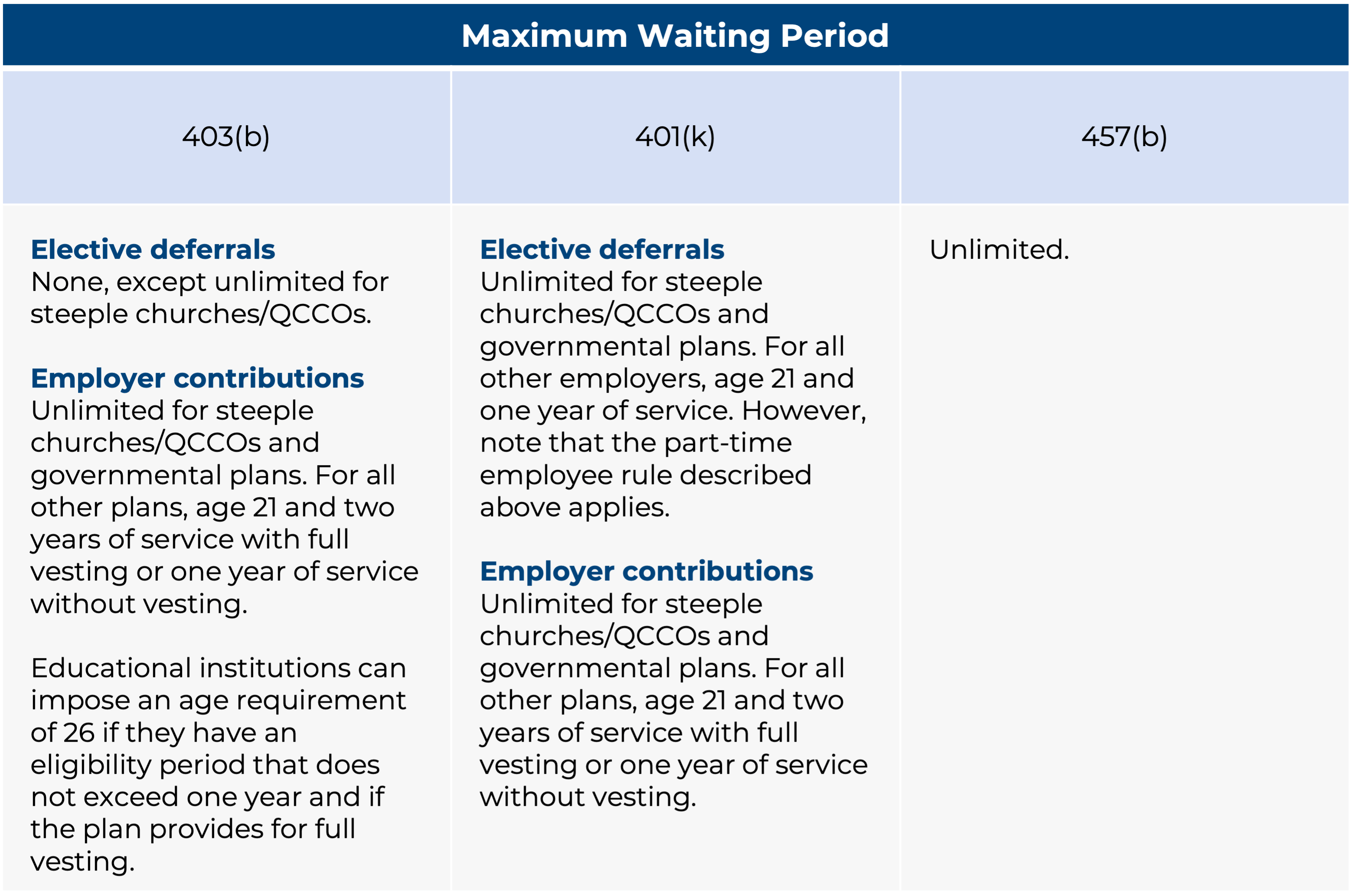

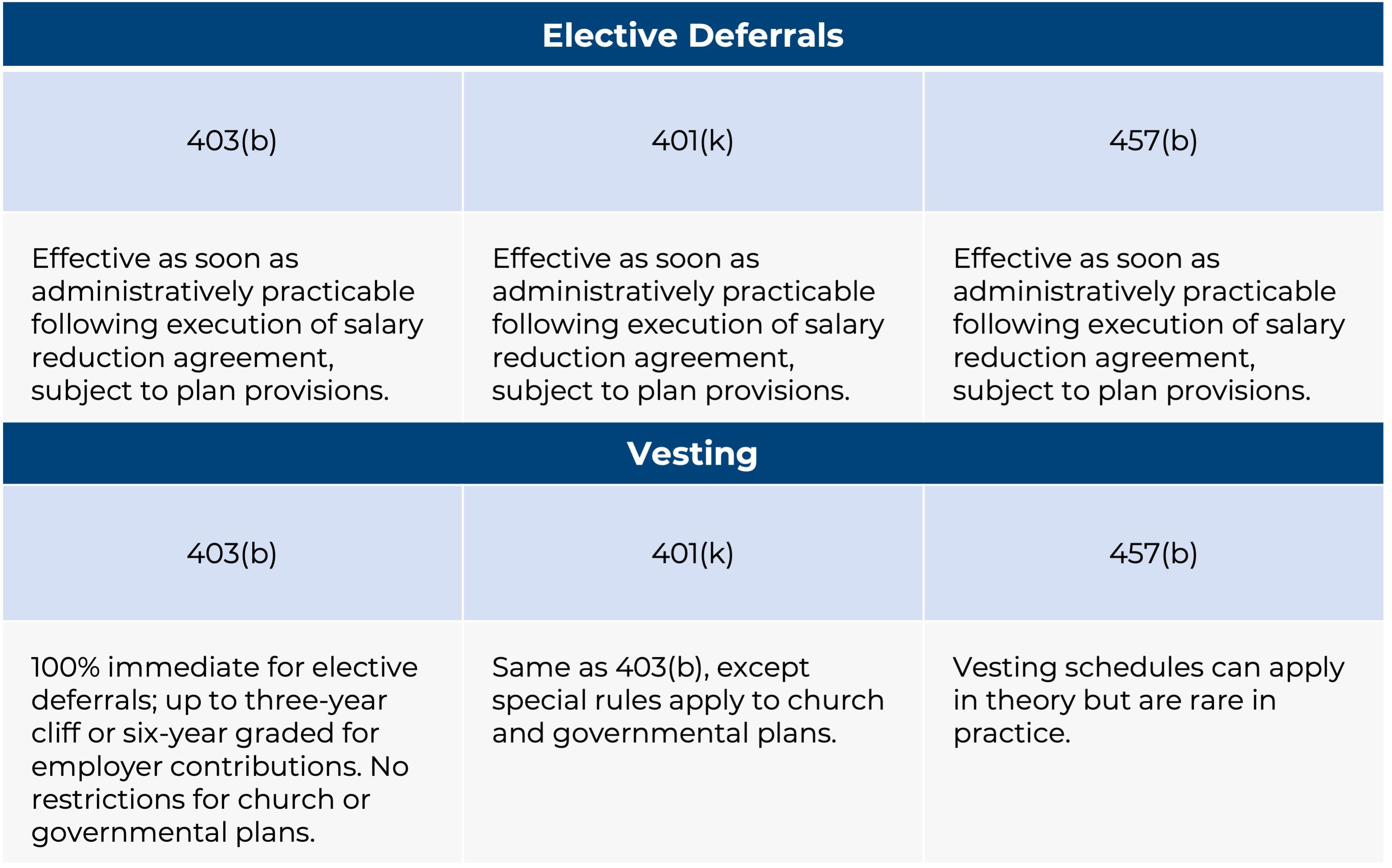

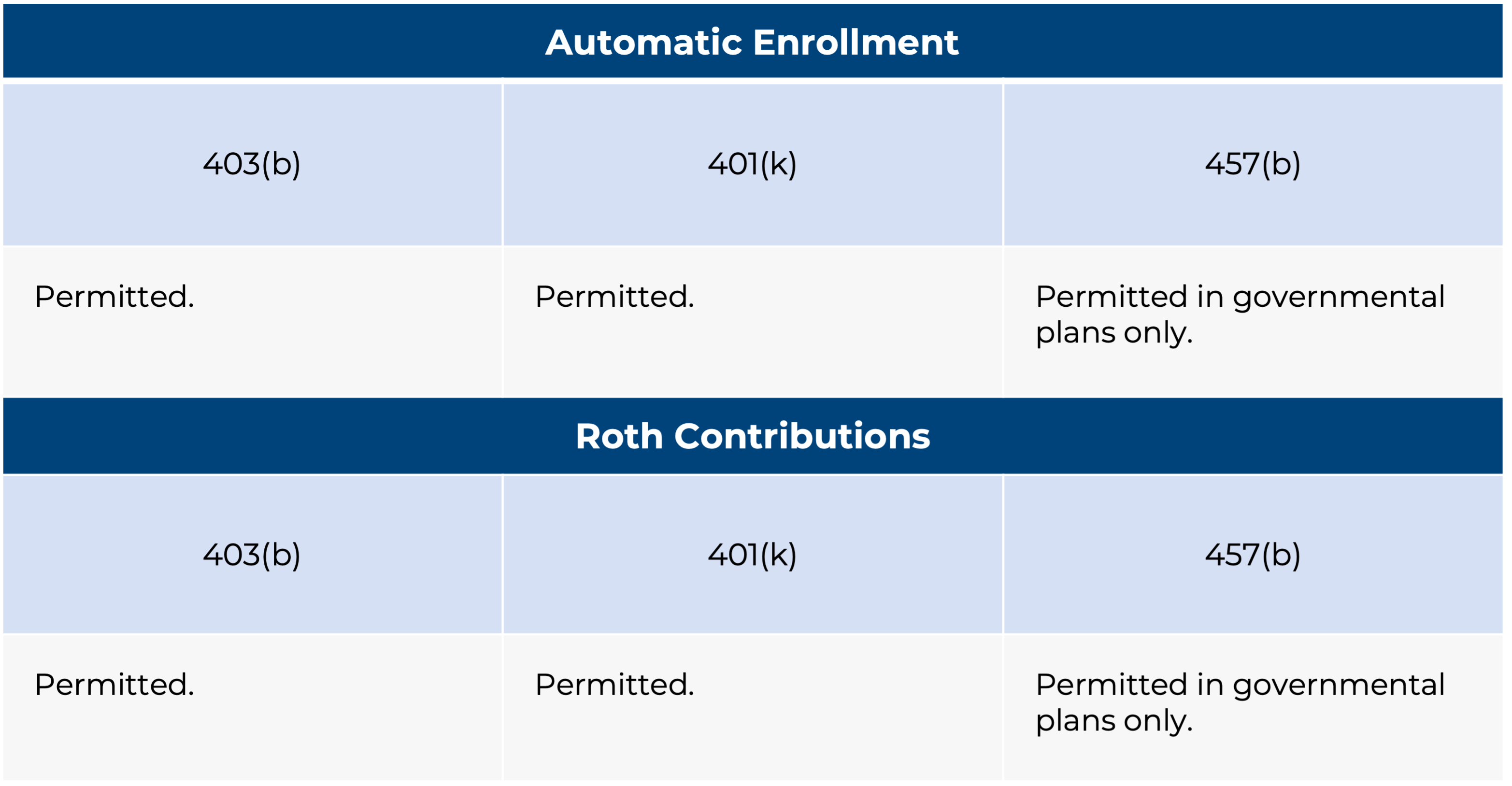

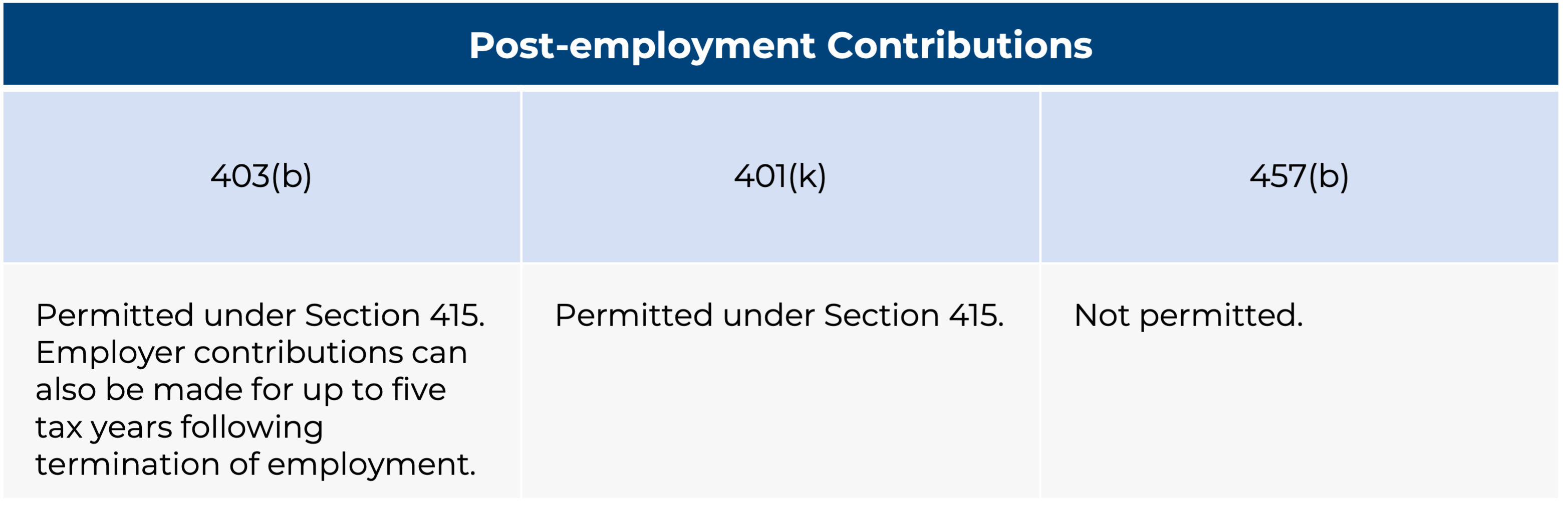

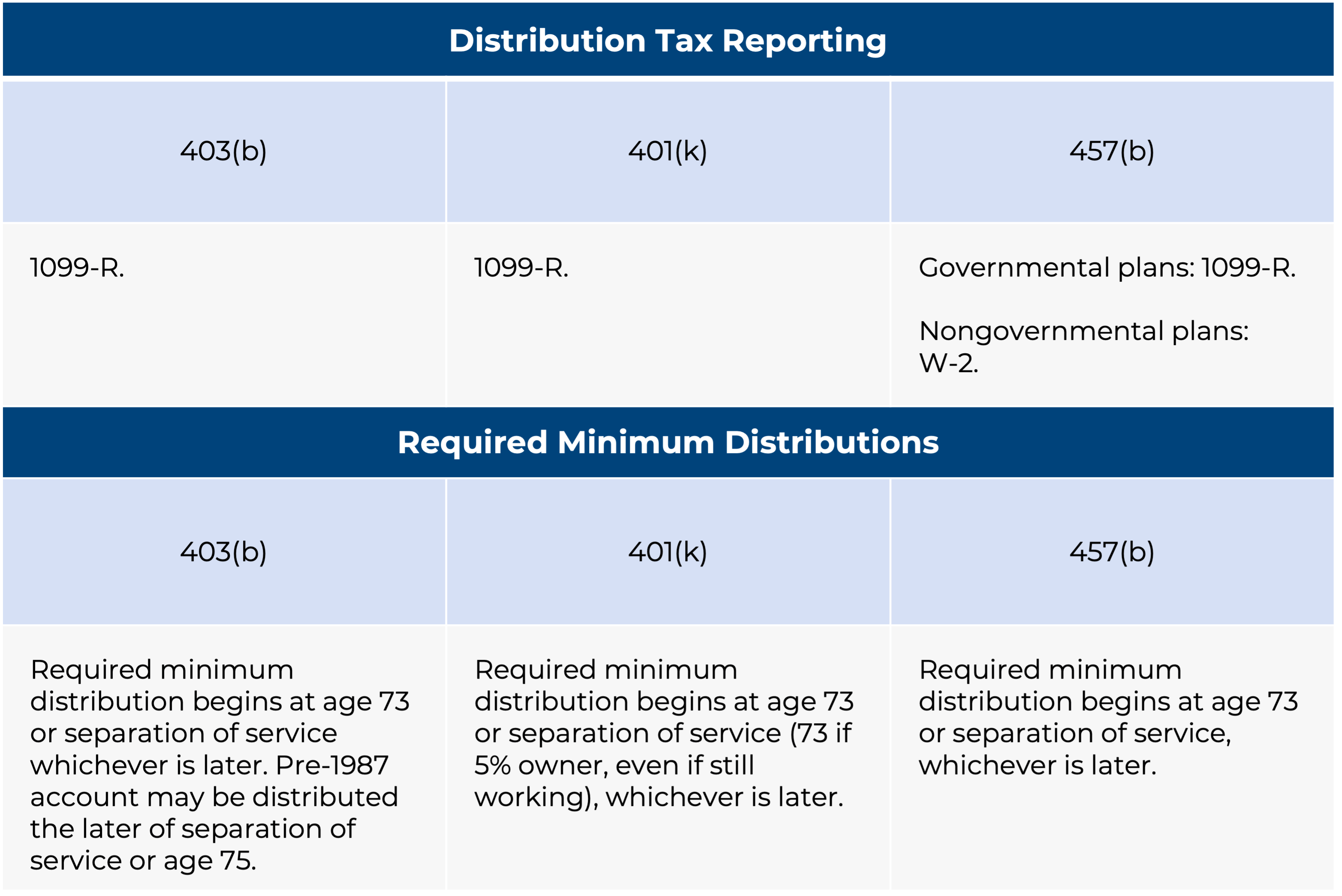

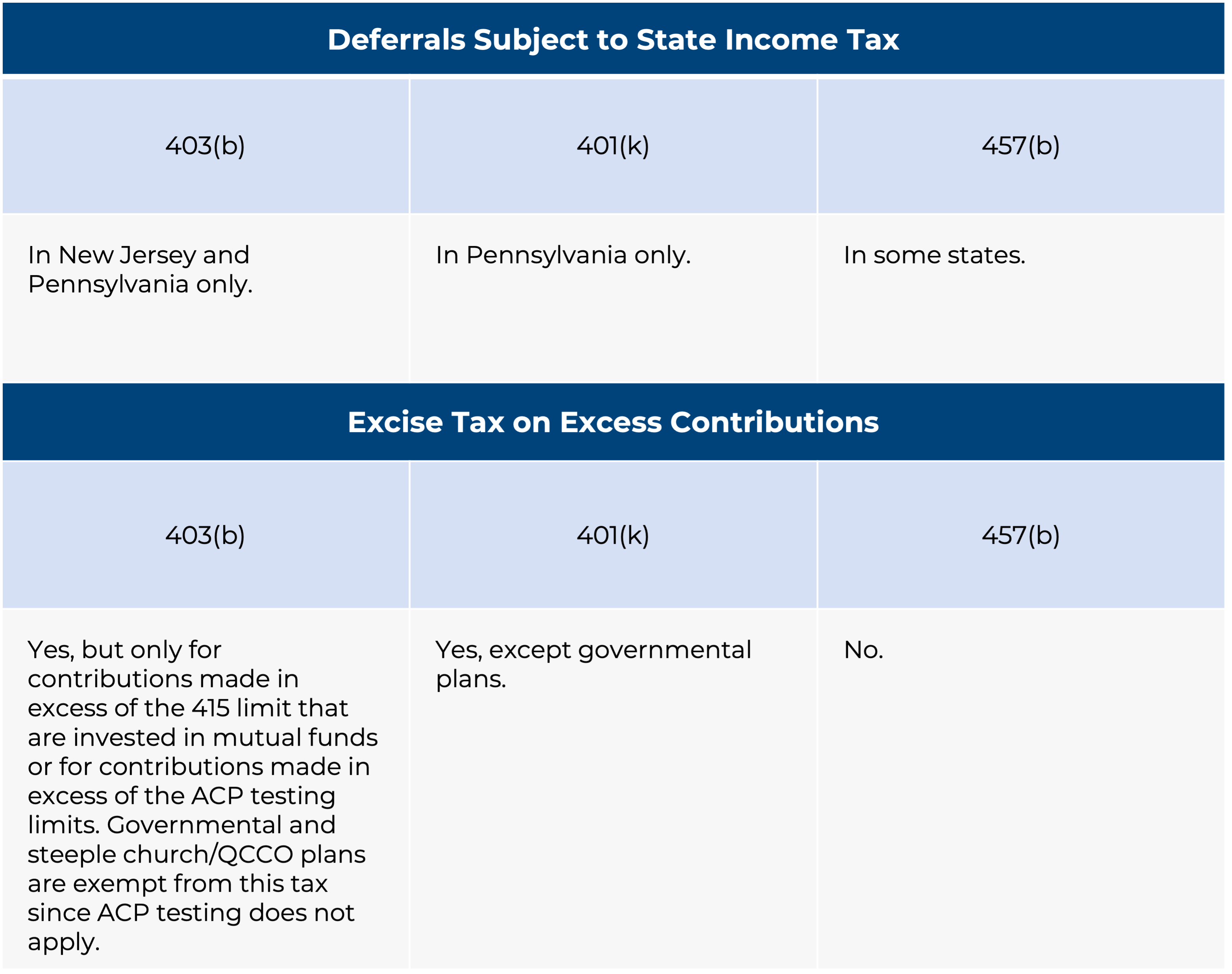

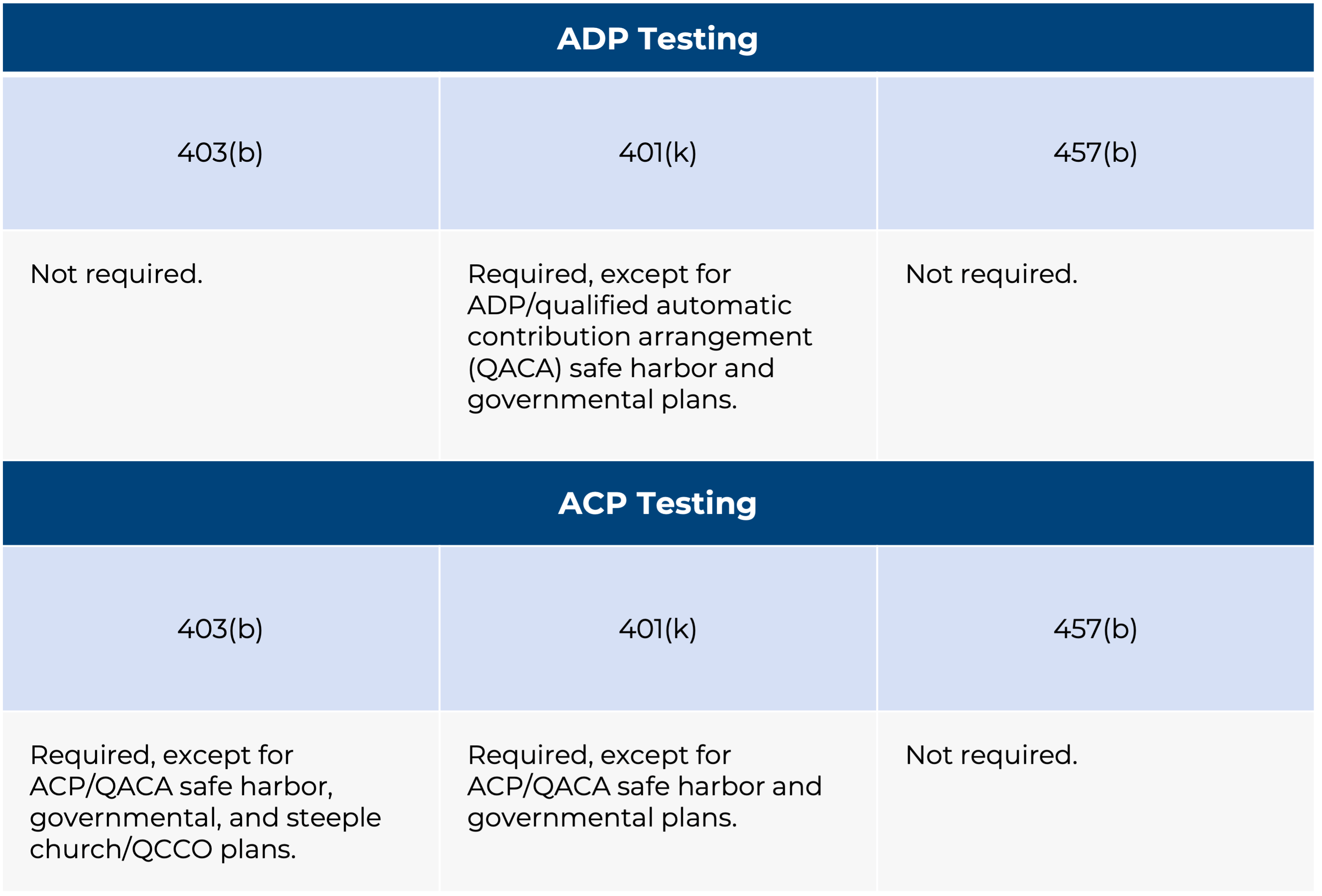

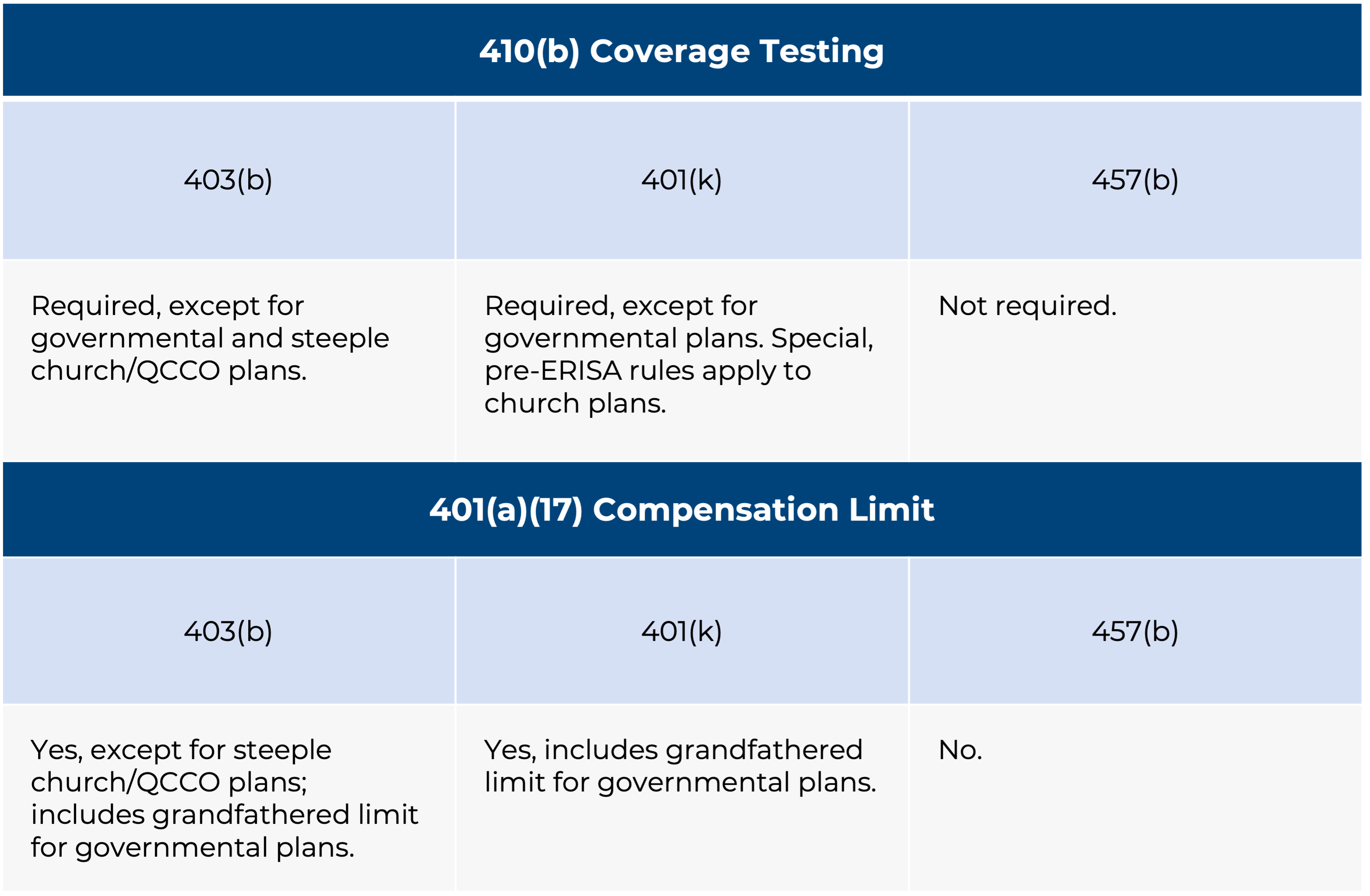

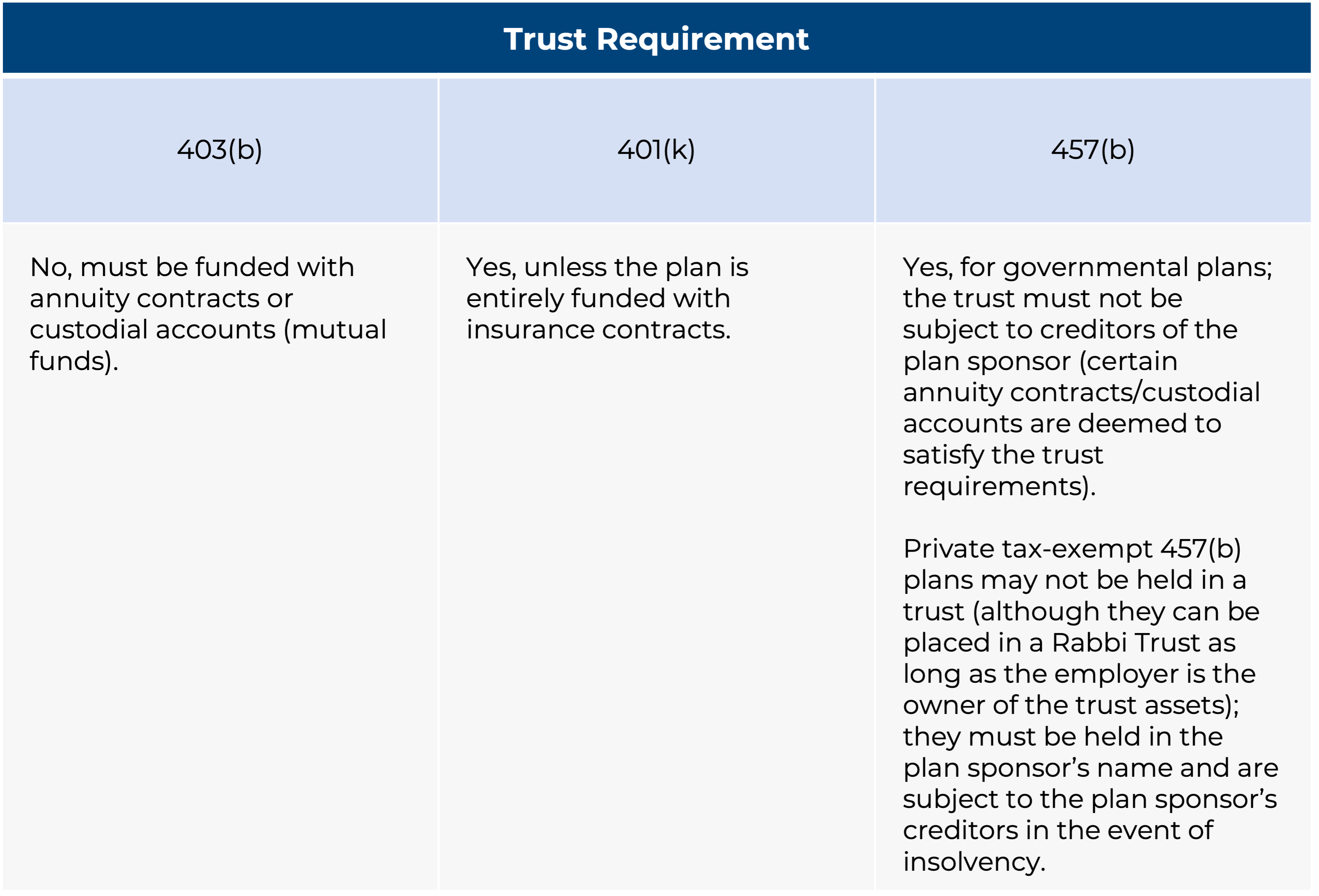

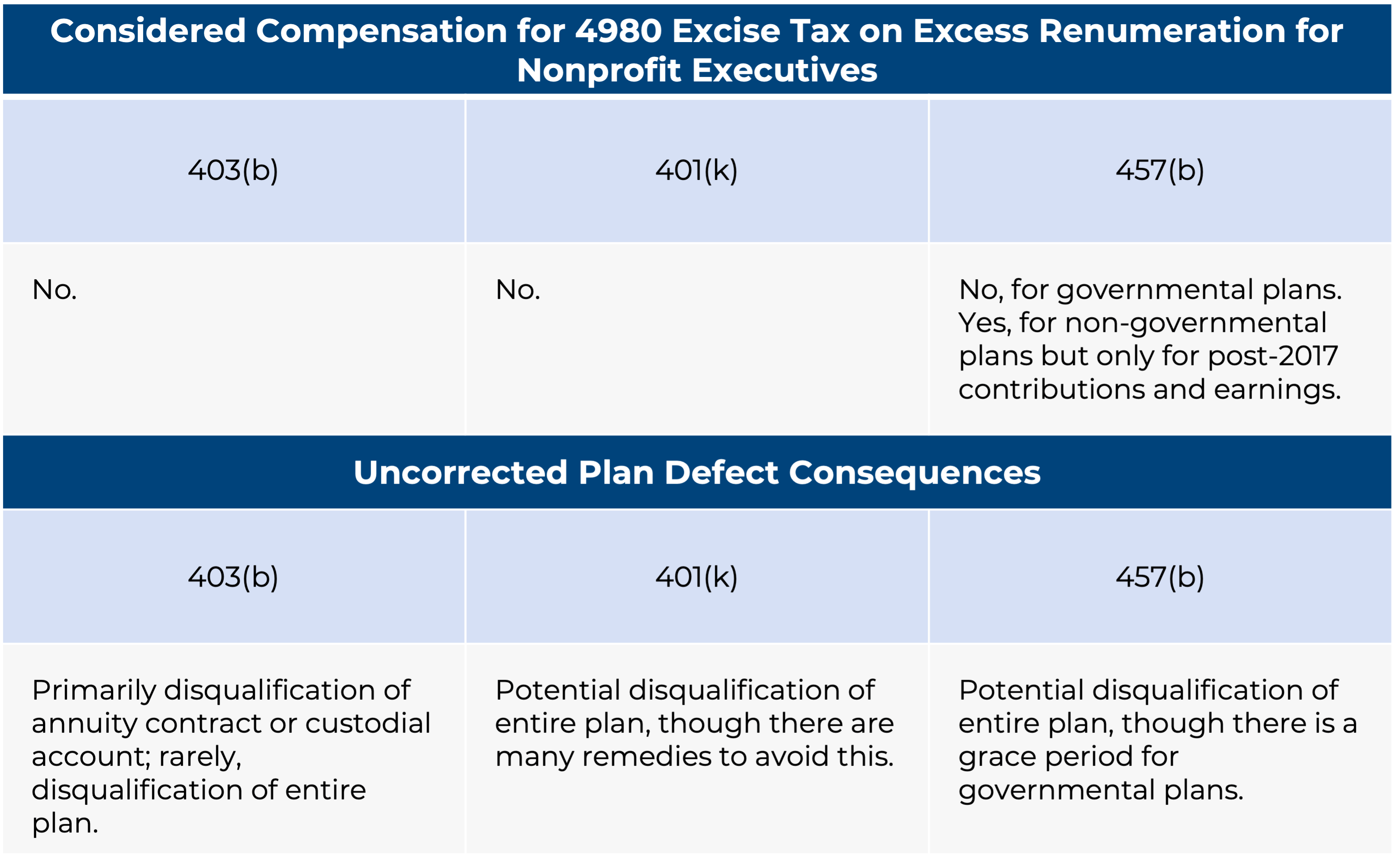

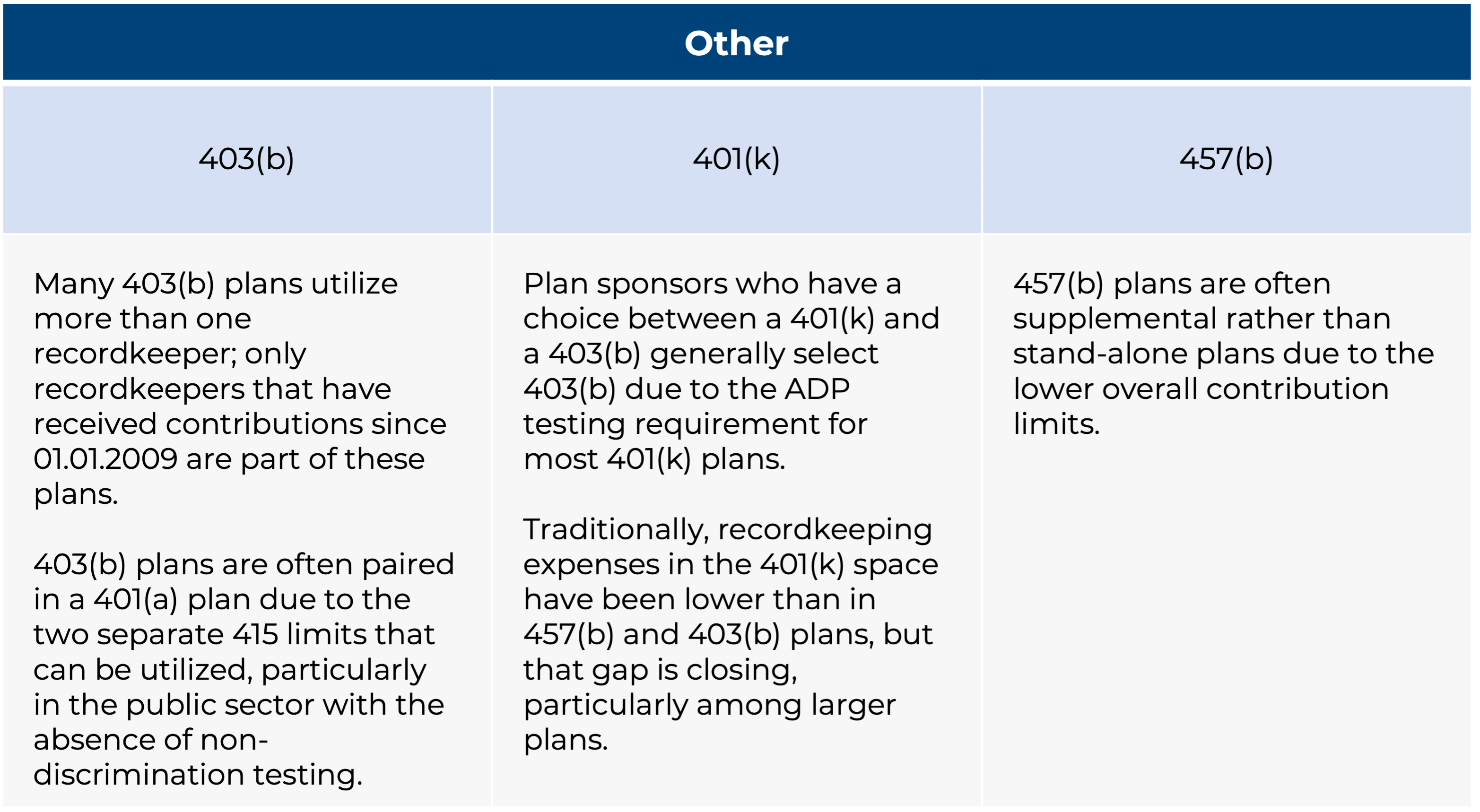

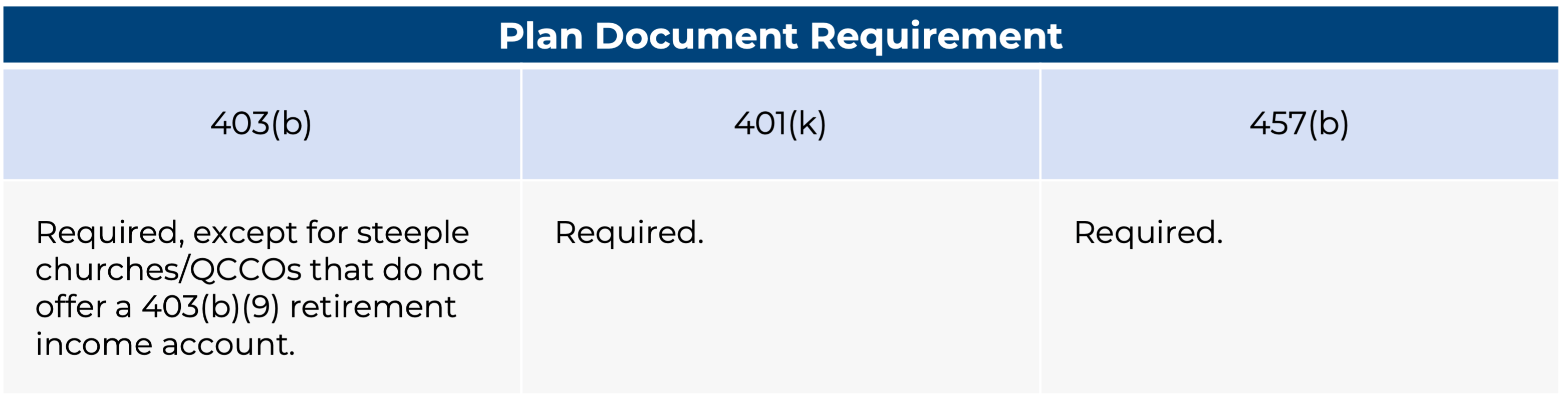

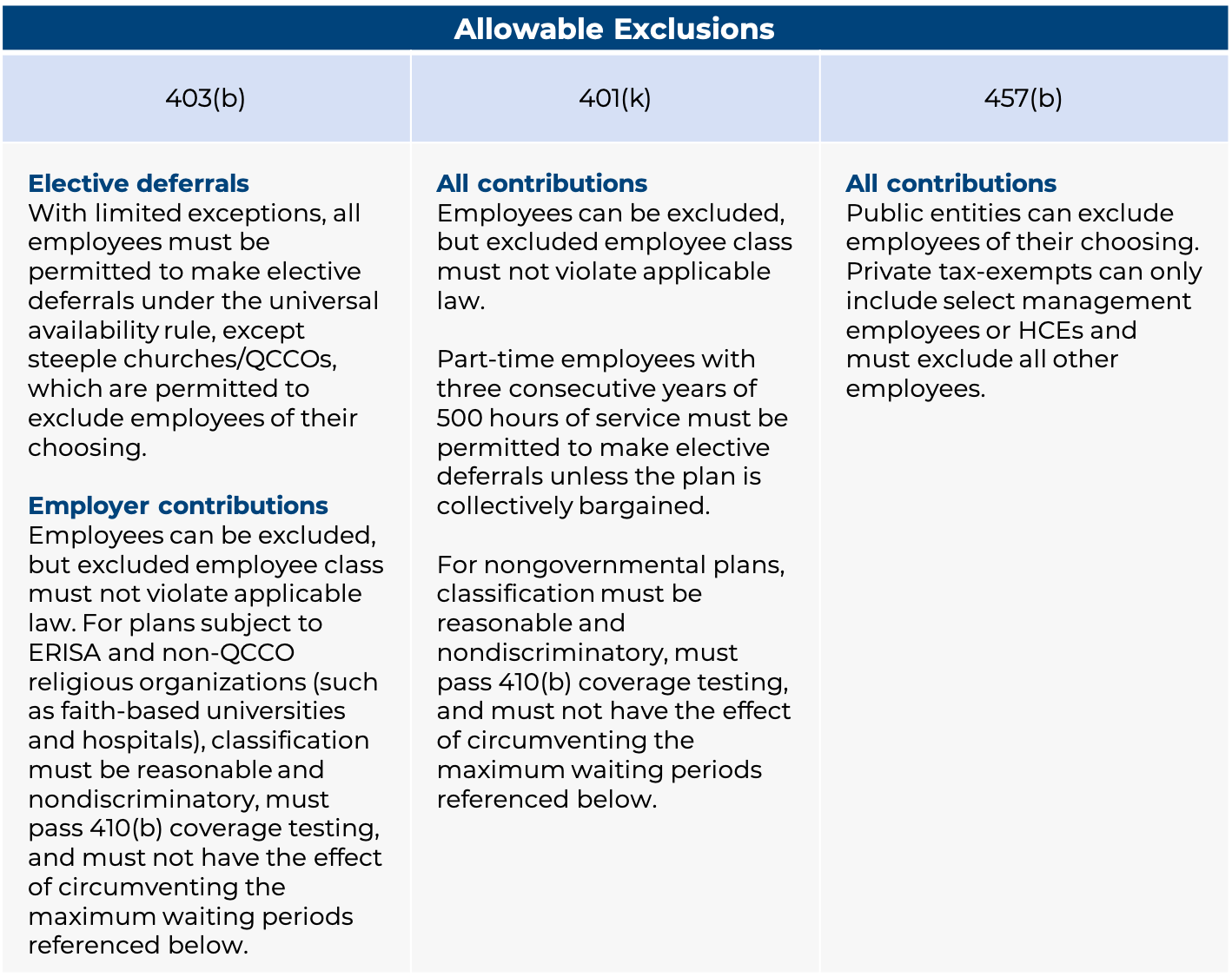

In addition to the key distinctions listed above, Figure One provides a comprehensive comparison of the remaining similarities and differences between 403(b), 401(k), and 457(b) plans.

Figure One: Digging Deeper into the Similarities and Differences of 403(b), 401(k), and 457(b) Plans