-

Solutions

- Solutions

-

Individuals & Families

- Individuals & Families

- Individual Investors

- Executives & Business Owners

- Families with Complex Needs

- Professional Athletes

-

Retirement Plan Sponsors

- Retirement Plan Sponsors

- Corporations

- Educational Institutions

- Healthcare Organizations

- Nonprofits

- Government Entities

- Endowment & Foundation Leaders

- See All Solutions

Comprehensive wealth planning and investment advice, tailored to your unique needs and goals.Investment advisory and co-fiduciary services that help you deliver more effective total retirement solutions.CAPTRUST provides investment, fiduciary, and risk management services for nonprofit organizations. -

About Us

- About Us

- Our People

- Our Story

- Learn About CAPTRUST

-

Locations

-

Resources

- Resources

- Articles

- Podcasts

- Videos

- Webinars

- See All Resources

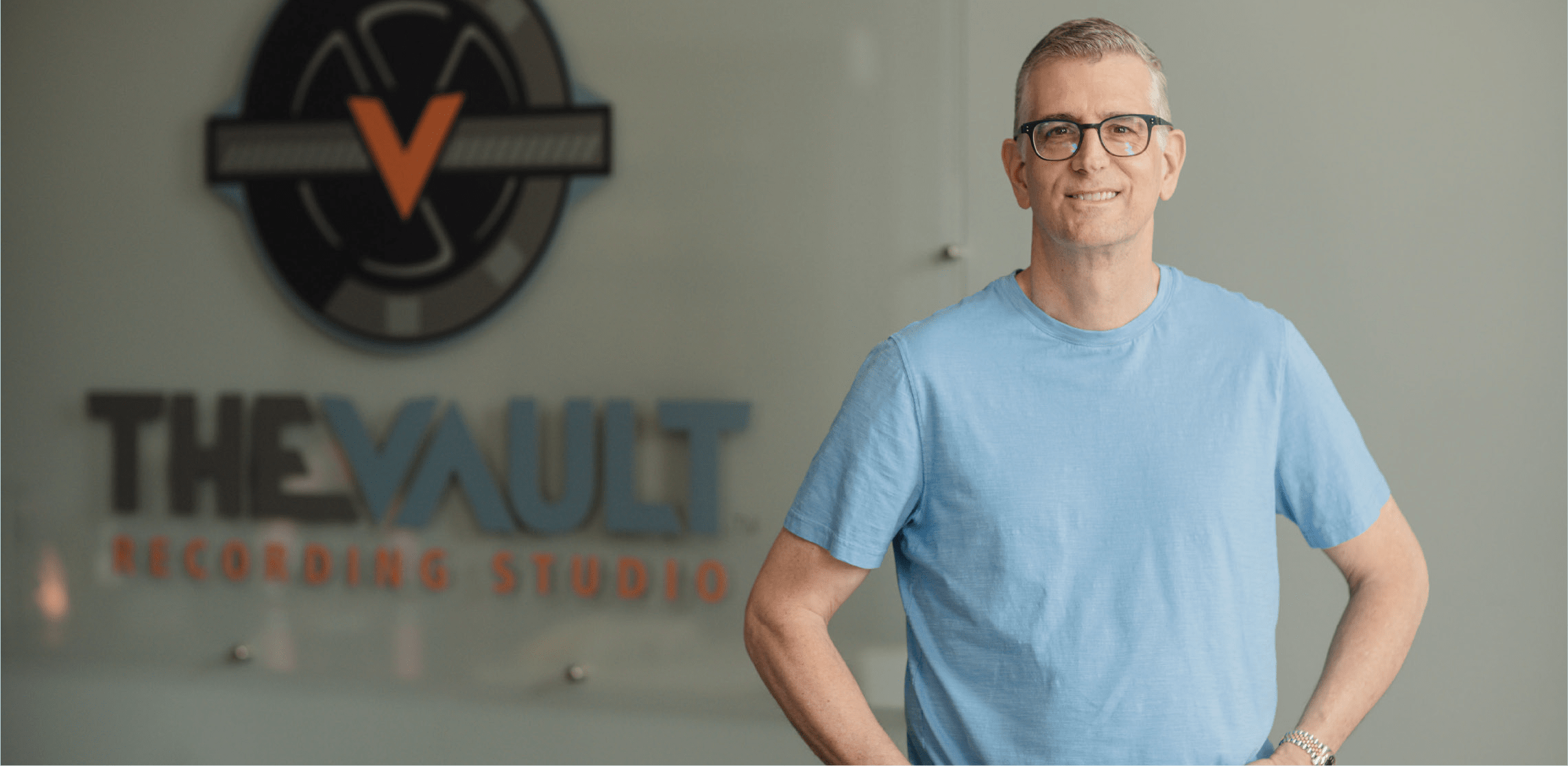

In 2018, McCutcheon left his position as the U.S. industrial products and Pittsburgh office leader at PwC, one of the Big Four accounting and consulting firms, to turn his family hobby, The Vault Recording Studio, into a commercial venture.

As founder and president of The Vault, McCutcheon found the ideal track for his second act.

“I learned early on that I had an artistic, creative side to me,” he says. “In the world of art, it’s called creativity. But in the world of business, it goes by a different name. It’s called innovation. It’s your ability to see the abstract and bring it to life.”

The Vault is a place where people tap into their innovative sides. “A recording studio is a magical place to be,” McCutcheon says. “There’s a feeling you get seeing a project come to life. It’s rewarding. Musicians know it. They don’t often have time to spend in a studio, so when they do, they make the most of it.”

Watch this VESTED Voices video featuring Bob McCutcheon to learn how a a corporate leader turned recording studio owner.

A Long Time Coming

Many of McCutcheon’s life experiences laid the groundwork for where he is today.

As a child, he pretended to be Glenn Campbell while strumming a toy guitar. In high school, he got a real guitar and played classic rock music in a band. He worked his way through college recording other artists’ music in his first recording facility, Alternative Studios, which he built in his mom’s garage.

Although he didn’t have formal training, he learned by trial and error. “A lot of it was experimentation,” he says. “The beauty of the recording arts is, technically, it’s art, not science, but there is a lot of science behind the physics of sound. It’s experimentation. If it sounds good, it is good.”

In 1991, he graduated from Robert Morris University, near Pittsburgh, with a double-major bachelor’s degree in business and finance. He chose those subjects because he wanted to run his own recording studio.

But instead, he landed a job with PwC and worked his way up the corporate ladder, enjoying every rung. “I realized I had an interest and a talent for business, accounting, and consulting. It was something I enjoyed. It happened to be an opportunity that was presented to me, and I took it.”

A couple of years after graduation, he met and married his wife, Dana. After their two children—Ryan and Brett—came along, McCutcheon’s daily time with music started to wane. He couldn’t juggle it all. “My hobby became almost nonexistent,” he says.

He figured his musical aspirations had been a phase of his life that was going to fade. “I kept a lot of my gear, but my guitars were in the closet collecting dust.”

McCutcheon says his career fulfilled him, so he was comfortable letting music fall to the back burner. “The firm offered me the ability to change jobs every couple of years. I was never doing the same thing twice. I was always able to innovate and find new and interesting things to do.”

But when his boys started to show an interest in music, his passion was rekindled.

Bob and Dana’s younger son, Brett, began taking piano lessons at age four. Later, Brett took up the saxophone and drums, started writing and recording music, and created his own YouTube channel.

Ryan found a passion for drums. He was drum captain in his high school marching band and played in a rock band in college.

As a way to spend time with them, McCutcheon built a small studio in their home, and the family played and recorded music together.

In 2016, on a flight home from Europe, he was flipping through the in-flight movie choices and stumbled on a documentary about the history of Sound City Studios in California. “It brought everything back,” he says. “I got off the plane, and thought, I’m in a position where I can do this now. Why am I not doing it?”

This was his aha moment. Finally, the time was right to do what he had always wanted.

Because of his role at PwC, McCutcheon knew how to conduct in-depth studies of different companies. “To serve my clients, I had to understand their industries,” he says. “My approach to starting the studio was no different. I studied the industry to learn about it.”

Once he felt he’d done enough research, McCutcheon wrote a plan, purchased an old bank building on Neville Island near Pittsburgh, and hired a firm that specialized in designing high-end recording facilities.

“At the time, it was still a personal studio project,” he says. “I was going to do my own recording on the weekends and evenings, but I knew I wanted to build it to commercial studio standards.”

The McCutcheon family funded the studio themselves. It was a passion project for all of them. In 2016, construction was complete, and The Vault was born, taking its name from the old bank vault in the basement of the building.

But he was still working in his corporate roles. “I was as busy as I had ever been with the firm. But we enjoyed the studio on the weekends with bands that I knew and with the kids. We were having fun doing recordings.”

Then, tragedy struck.

Loss and Clarity

In September 2017, Ryan, 19, was killed in an automobile accident while returning to his college campus after a long day assisting high school drum students at a local band festival.

“The best we can tell is that he fell asleep at the wheel,” McCutcheon says. “Everything was turned upside down in a heartbeat. Everything just froze.”

McCutcheon took several months away from the firm. “I started to question what I wanted to do and what was important in life. It probably took me a year or so to assess where my heart was,” he says.

The loss changed him. “I just don’t look at things the same way I did prior to that. It was a defining moment. The things I value are very different now. You realize it’s about relationships. It’s about community. It’s about family.”

In December 2018, he retired, determined to spend more time with Dana and with Brett, who was still in high school. To cope with their loss, the McCutcheons found ways to give back to the community, often via music, with Ryan in mind.

The family established the Ryan McCutcheon Rhythm19 Fund with The Pittsburgh Foundation to support children’s love of music in a variety of ways. “We are keeping Ryan’s memory alive,” Dana says. “We mention Ryan’s name every day.”

Pumping Up the Volume

Trying to get back on track after the loss of their son was difficult. “We had just started The Vault label,” McCutcheon says. “It was hard to reenergize.”

He began expanding the studio beyond a small family affair to a world-class recording facility. Although Brett and Dana are still intricately involved in The Vault, McCutcheon also hired a roster of world-class producers and engineers.

One big step was the addition of Grammy Award-winning Jimmy Hoyson—who had previously worked with Michael Jackson, Eric Clapton, B.B. King, and other famous artists—as the studio’s chief engineer.

Hoyson told McCutcheon, “If you want to play big, you should find a Neve recording console.” And McCutcheon agreed. “Anybody who knows anything about vintage gear would love to get their hands on a Neve,” he says. “It offers such a warm, punchy vintage sound.”

They figured it would take 12 to 18 months to find one, but they hit the jackpot when, just a few weeks later, they discovered a restored Neve 8058. Later, they learned it once belonged to George Harrison of the Beatles.

McCutcheon’s goal for The Vault is to provide opportunities and services for those who are trying to make a living in the world of music. In the past five years, he estimates that hundreds of artists, many from Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia, have worked in the studio, including Chris Jamison, who finished third on NBC’s The Voice.

“When we first opened the studio, most days, I was the only one in the building,” McCutcheon says. “Now there are people walking in the halls every day.”

The Vault is drawing impressive professionals in sound engineering to build a powerful roster of producers. About half a dozen independent engineers and producers work out of the facility, as does McCutcheon, who also produces and engineers music.

Does he think The Vault has a chance to discover a breakout artist with a hit record? “That’s not why we do what we do,” McCutcheon says, “but it would be nice to have.”

“In the back of your mind, you hope it’s something that’s going to happen,” he says. “I’m surrounded by people who have had that happen multiple times. It just hasn’t happened from this building yet. But having these people here increases our odds.”

McCutcheon says he learned early in his career that successful people surround themselves with good teams, so that’s what he has done at The Vault.

Financially, the studio is self-sustaining, he says. “But I’m not getting rich doing this, and I’m not using this to support my family, which it was never intended to do. Even when it is making money, I’m putting that money back into the business. I’m funding my passion.”

Continuing to Grow

The McCutcheons recently renovated a second property, an old gas station across the street, to use as a multipurpose facility for charitable events, plus camps and other activities for students who want to learn about the music industry.

McCutcheon says he hasn’t had any doubts about his decision to open The Vault. “One of the things that I’ve learned throughout my career, and to be honest, solidified in my mind after the passing of my son, is that your passions define the core of who you are.”

“I feel fortunate that I had a clear understanding of what my passion was,” he says. “Then, I had a life event that made me slam on the brakes and question what I was going to pursue. I decided I was going to pursue what I was passionate about.”

“I wouldn’t say that my journey went according to plan,” he says. “But it’s ironic that things have completely turned around, and here I am after my retirement, still doing what I originally wanted to do.”

Research suggests Reeg is on to something. Older adults who build meaningful bonds with younger people, whether in their families, workplaces, or communities, live longer and happier lives. In fact, one long-running Harvard study recently found that social connection is the strongest predictor of well-being as we age. Bonds with younger people are particularly powerful happiness boosters, the research shows.

“Connection of any kind counters loneliness, which is especially common among youth and older adults,” says Kasley Killam, founder and executive director of the nonprofit Social Health Labs. Loneliness in older adults is linked with dementia, heart disease, and premature death, according to the National Institute on Aging.

Connecting with younger people is “a chance to be in touch with where the world is going” and to feel a greater sense of purpose in that world, says Katharine Esty, an 88-year-old psychologist and author of the book Eightysomethings. But to bridge the gaps, it helps to understand more about who is on the other side.

Beyond Bashing

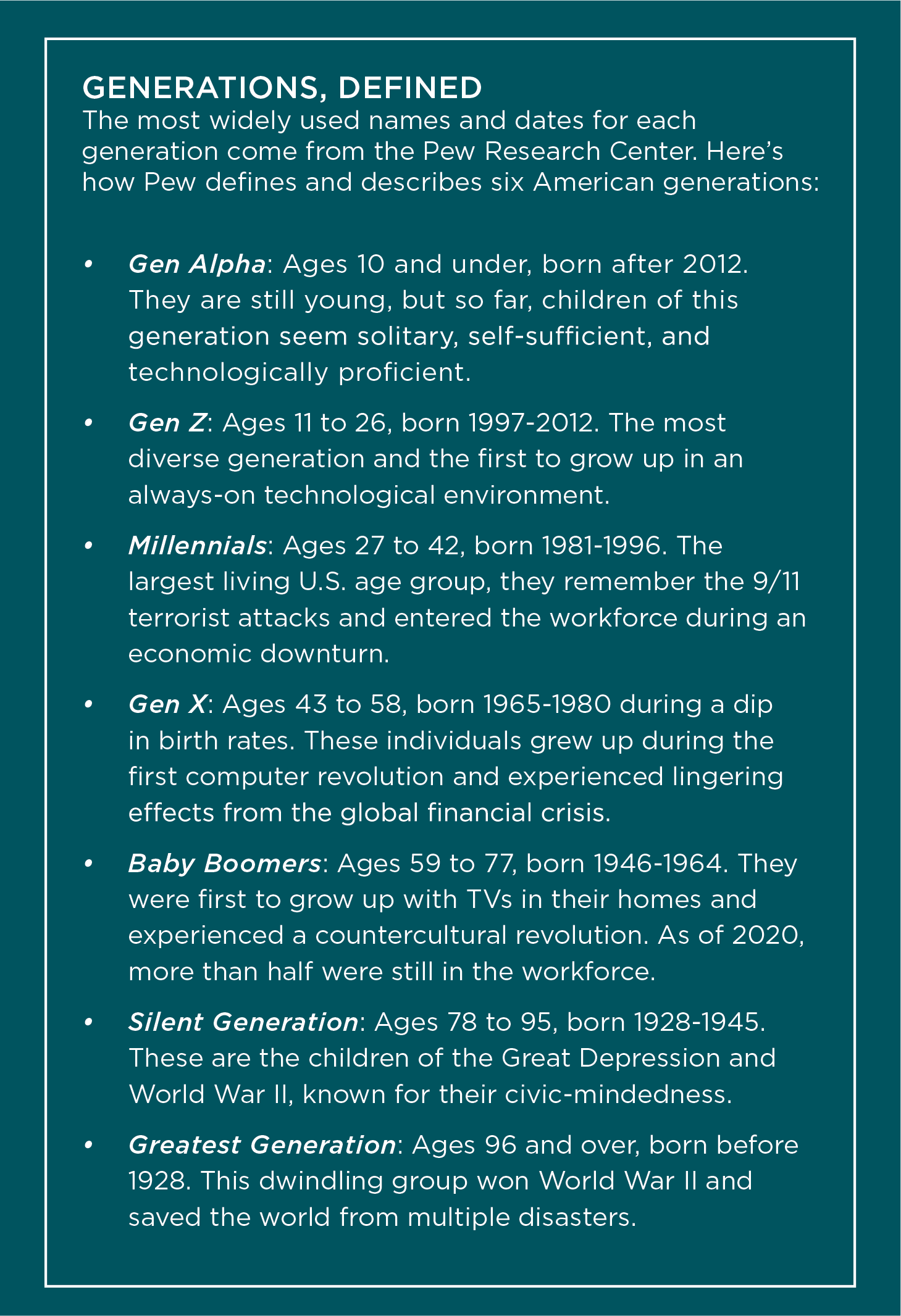

Baby boomers were once viewed as being too revolutionary. Gen Xers were slackers. Millennials were entitled. And today’s young adults, members of Gen Z, are often branded as overly sensitive snowflakes, writes Megan Gerhardt and her colleagues in their recent book Gentelligence: The Revolutionary Approach to Leading an Intergenerational Workforce.

A few years ago, Gen Zers hit back with the “OK, boomer” retort to dismiss “older people who just don’t get it,” The New York Times reported. Gerhardt, also a Miami University business professor, says this type of generation bashing is downright unproductive, pushing people farther apart instead of helping them find a middle ground.

But understanding how each generation is different and unique can help people build stronger social ties, says Roberta Katz, a senior research scholar at Stanford University and co-author of Gen Z, Explained: The Art of Living in a Digital Age. The book is based on interviews, surveys, focus groups, and social media posts from teens and young adults born after the mid-1990s.

The young people who Katz and her colleagues spoke with when writing the book pushed back on the idea that they are fragile, coddled, and unable to deal with the world beyond their phones, she says.

Everyone who is alive today is experiencing the same technological and social upheaval, says Katz. “The difference is that’s the only world Gen Z knows. And we don’t know what the world looks like from their vantage point. We assume we do because we were young once, but we don’t really know.”

People born into Gen Z—that is, between 1997 and 2012—are “burdened by what feel like existential threats to their future,” such as climate change and school shootings, Katz says. They are wary of authority and hierarchy, something their schools and employers are grappling with. But, she says, they are eager to work collaboratively to solve the world’s problems.

They also are less glum than generally thought, says Sophia Pink, a 26-year-old doctoral student at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business. As an undergraduate at Stanford, Pink spent a summer interviewing fellow 21-year-olds around the country and learned that “they were pretty optimistic about their own lives and their own plans,” even as they despaired for the wider world.

It is true, Katz says, that younger people spend a lot of time on their phones. They can be impatient when older people don’t understand or follow their digital ways—for example, when their parents or grandparents send emails and leave voicemails although a simple text would do. But, she says, they do crave meaningful connections with others, including older people in their lives.

Reeg says she’s learned exactly that by spending time with her grandchildren. “If I have one of my grandkids in the car with me, and they’re looking at their phone while I’m talking, I just want to scream, take the phone, and throw it out the window. But I’ve learned that they can multitask better than we ever could. And actually, they are listening.”

There’s some truth to the idea that younger and older people “live in different worlds” and “speak different languages,” says Esty. Misunderstandings and hurt feelings can go both ways, she says. “Older people can feel ignored and not taken seriously,” just as younger people can.

But overcoming these barriers is worth it.

Photo above: Christeen Reeg and her grandchildren

“Older adults have wisdom and experience,” Killam says. “The younger generation brings a fresh perspective.” And connecting across generational divides can bring a greater sense of happiness and purpose for people of all generations.

Jumping the Chasm

Sometimes, bridging generational gaps can be particularly challenging. For example, consider a family in which grandparents and young adults have become estranged from each other for any number of reasons. In these cases, it’s important to remember that big emotions tend to fade over time and that past hurts can be easier to resolve than most people expect.

The more common problem, Esty says, is that “people don’t make the effort.” Since the first steps are usually the hardest, it helps to make them small.

That might mean doing what many older people did for the first time during the pandemic: using Zoom and FaceTime to meet up virtually with family, friends, and colleagues. People were craving human connections and leaping over technological divides to make them, social scientists say.

Older adults who now play online video games, use apps to watch movies with faraway friends, or swap daily Wordle scores with their children and grandchildren have made similar leaps. So have those who’ve become avid texters—even if they do use more punctuation and fewer emojis than their younger contacts would prefer.

Reeg says she tries to text each of her grandchildren at least once a week. “I’ll go through pictures, and I’ll see a memory picture, and I’ll just send it and say, ‘Thinking of you.’”

But older adults should not feel obligated to use digital technologies they don’t like. “Be true to yourself, and if you hate it, then don’t do it,” Esty says.

Pink says younger adults do understand that not everyone wants to use text or video chat. That’s why she calls her own grandparents on their landline.

Likewise, older workers don’t have to adopt all the technological tricks and habits of their younger colleagues, says Marci Alboher, a vice president at CoGenerate, a group that focuses on bringing multiple generations together to do good work. But, she says, everyone benefits when they can share favorite tools, like Zoom, Google Meet, or WhatsApp.

Beyond Tech Tools

Alboher says it’s wrong to assume that all younger people prefer texts and instant messages or that all older people prefer emails and phone calls. It’s better, she says, to ask. “If you are starting to work with someone or you’re joining a team, you can have a conversation about norms and preferences. You may expose yourself to some new communication styles, and you may find that people are suddenly more responsive to you.”

But don’t discount the value of a good in-person conversation. Katz says, in her research, one revelation was that young people valued in-person interactions above all others. “They are very much about human connection,” she says. “They want to be seen, and they want to be heard, just like everyone else.”

When you have those conversations, she says, be sure to listen, not just talk. “Don’t be judgmental. Ask them about their lives.”

Sometimes, connecting with younger people means “stepping out of your own comfort zone” and getting past the way they are “dressed or groomed or adorned,” says Lauren Lambert, a CAPTRUST financial advisor based in Boston, Massachusetts, who has advised multigenerational households, mentored younger colleagues, and raised two millennial children. “It’s important to respect them and their struggles. You really have to listen to them and remember what it was like to be their age.”

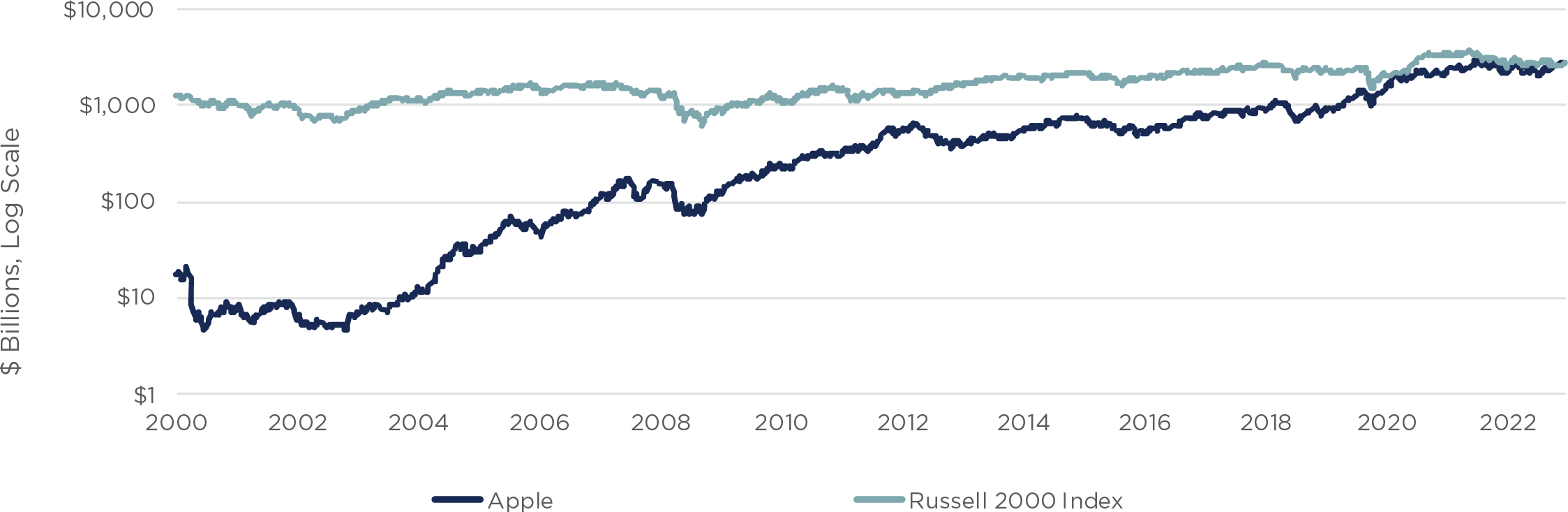

In the mid-1990s, after a string of product failures, Apple teetered on the brink of bankruptcy. But in 1997, one of the company’s founders—the legendary Steve Jobs, who had been ousted a decade earlier because of internal conflict—returned to the company and launched what has become an almost unbelievable story of resurgence.

As shown in Figure One, the investment result has been astounding. Over the past 23 years, the market capitalization of Apple alone has eclipsed that of the entire Russell 2000 Index. To wrap your head around the size of this rebound, consider this: $1,000 invested on the day before Steve Jobs’s return as interim CEO in 1997 would now be worth more than $1,000,000.

Fast forward to 2023, and it’s not just one company or security that is standing on the brink of revival. Rather, it is broad swaths of the largest and most liquid investment asset class: the bond market.

Figure One: Apple’s Market Capitalization vs. the Russell 2000 Index

Sources: Bloomberg, CAPTRUST

The Bond Market Slump

Following the first back-to-back negative annual returns for core bonds since the inception of the Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index in 1976, conditions now seem ripe for a rebound. Core bonds are experiencing positive returns so far this year. But even more promising is the view that today’s significantly higher yields, coupled with the added potential for price appreciation, have increased the prospects for future returns more than at any other time in recent history.

Several factors weighed on markets last year, including an inflation shock and the Federal Reserve’s aggressive policy response. Inflation plays a major role in the bond market because it erodes the purchasing power of fixed income payments and can drive real yields—that is, the income from bonds after adjusting for inflation—into negative territory.

To fight inflation in 2022, the Fed acted forcefully, raising the fed funds rate a total of seven times, from 0 percent to 4.25 percent. This was followed by three more hikes in the first half of 2023, bringing the rate to 5 percent, with the potential for further increases.

While stocks were impacted in this rising-rate environment, it was bond investors who were most surprised by the setback. Core U.S. investment grade bonds, for instance, suffered a 13 percent loss, their worst return since the inception of the Barclays index.

Here, it is important to note that bonds offer two distinct sources of return: coupon payments and the potential for price appreciation. While coupon payments represent a steady source of income until a bond matures—assuming the issuer does not default—the price of a bond adjusts continuously based on prevailing interest rates.

For an investor who holds a bond to maturity, these price fluctuations are irrelevant. However, they’re an important piece of understanding the total return of a bond.

The Opportunity

Compared to the past decade, when yields were exceptionally low, the income generated by bonds now provides a more substantial cushion to counterbalance price declines caused by rising rates. Today, intermediate investment grade corporate bonds yield approximately 5.5 percent, up from 2.4 percent at the end of 2019.

This means that even if interest rates continue to rise gradually, bond yields have a much better chance to offset price declines, making a repeat of steep 2022 losses less likely in the near term.

Additionally, the current rate environment has improved the risk-reward trade-off for bonds compared to stocks. When corporate bond yields were below 3 percent, as was the case for most of the 2010s, even conservative investors seeking income had to explore alternative options. This led to a phenomenon known as there is no alternative (TINA), prompting many people to invest in stocks. However, with bonds now offering robust yields that exceed inflation, the mantra has shifted to there is now an attractive alternative, or TINAA.

The takeaway: Despite continuing economic uncertainty, bonds may now represent a more compelling opportunity than they have in years.

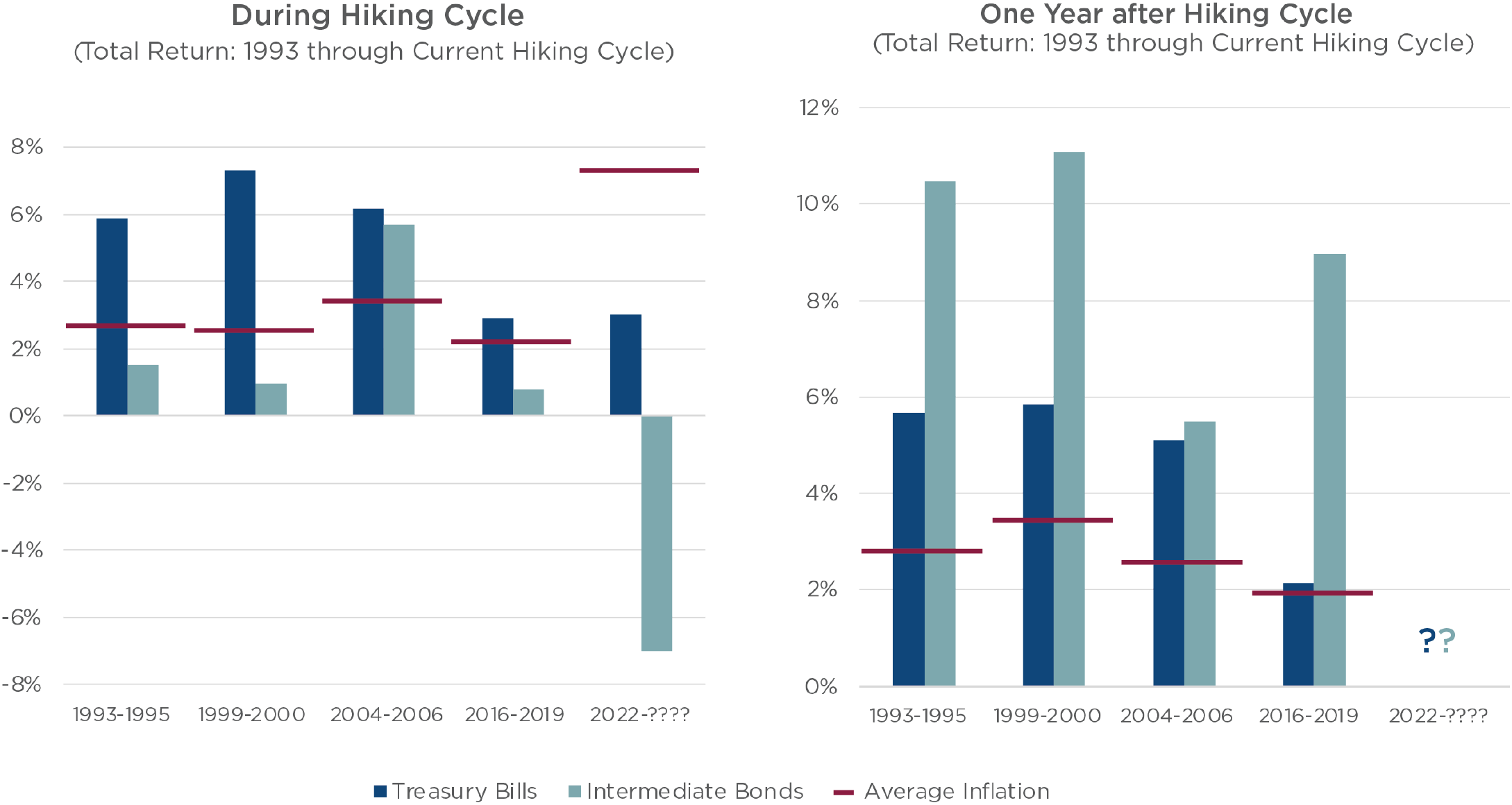

Figure Two: Treasury Total Returns during and after Hiking Cycles

Sources: Bloomberg, CAPTRUST

Bonds and Fed Tightening Cycles

The rate-hiking cycle that began in March 2022 represents the fastest and most aggressive move by the Fed since 1981. However, a significant distinction exists between now and then. While the fed funds rate was 16 percent at the start of the 1980s hiking cycle, it began 2022 at 0 percent. Essentially, the Fed’s tightening policy has begun to normalize interest rates amid its ongoing battle against inflation. This process of normalization has created a wide range of scenarios that could benefit bond investors through both higher yields and greater potential for price appreciation.

Recently, investors have grown anxious that higher rates, among other economic challenges, will push the U.S. into a recession. When anxiety grows about the state of the economy, investors tend to seek safe-haven investments and often flock to Treasury bonds. Higher demand for Treasurys drives their yields lower but their prices higher—a pattern that has repeated itself across previous hiking cycles.

As shown in Figure Two, bond returns are typically subdued during hiking cycles, with short-term bonds and Treasury bills outperforming longer-maturity bonds because they can be swiftly reinvested in the rising-rate environment. The left chart illustrates the combination of low initial yields and aggressive rate hikes. Since 2022, intermediate-term U.S. Treasury bonds have lost nearly 7 percent, while short-term (1 to 3 month) Treasury bills have shown positive returns of 3 percent. Adding to investor pain is the elevated level of inflation, represented by the red horizontal lines. This dynamic could compel investors to concentrate their bond investments in shorter-term securities like Treasury bills or even money market funds.

However, history shows a significant shift once the Fed’s hiking cycle is over. The right chart illustrates this trend. When the Fed maintains steady rates or begins cutting rates, it can trigger a bond rally that benefits longer-duration bonds, resulting in substantial price increases for those bonds.

Strategies for Investors

With money market funds now yielding 5 percent, investors may be tempted to load up on short-duration bonds to take advantage of these high yields with little or no price risk. This is particularly true given the current inverted yield curve, a relatively uncommon phenomenon when shorter-maturity bonds provide higher yields than bonds with longer maturities.

However, as with any investment strategy, there are risks in overconcentrating on any single type of investment, even safe, short-term Treasurys. Specifically, such investors face reinvestment risk—the risk that when a bond matures, interest rates may be lower than when it was bought, forcing the investor to reinvest at a lower yield.

There are three primary strategies bond investors can use to take advantage of attractive short-term yields while constructing a durable portfolio that is well-positioned for a range of potential future environments.

- A barbell is a tactical strategy that pairs bonds at different ends of the maturity curve—that is, both short- and long-term bonds. A barbell strategy represents a compromise, providing investors with the benefits of low-risk, higher-yielding short-term securities plus the lower reinvestment risk of longer-term bonds. If recession fears rise and investors rush to safe-haven assets, such as 10-year Treasurys, the barbell strategy could provide an effective hedge against risk.

- A bond ladder is a portfolio of bonds with staggered maturities. This serves to mitigate reinvestment risk and smooth out yield fluctuations. As bonds mature, the cash returned can be reinvested at the end of the ladder, allowing the investor to benefit if rates have risen. But even if rates have fallen, the investor can still benefit from earlier rungs on the ladder that retain higher yields. In addition, bond ladders can be structured to generate a consistent monthly income stream.

- Sector diversification across different bond categories is another way to enhance portfolio resiliency and tap into the potential for attractive risk-adjusted returns. However, navigating some corners of the fixed income market can be challenging due to nuanced risks and often hard-to-access information. Institutional-quality active managers with specialized expertise and resources may represent the best way to access these more specialized sectors.

As interest rates normalize from artificially low levels, the bond market seems well-positioned for a triumphant return. However, this does not mean investors can simply choose a bond strategy and then set it and forget it.

A wide range of dynamics will influence the fixed income landscape in 2023 and beyond. A prudent approach to the new bond market means intentional diversification in terms of maturity, sector allocation, and management style that matches investors’ risk tolerance and time horizon. Fortunately, the enormous size and robust diversity of the bond market provides a variety of securities that can be employed to create a diversified strategy.

Investment success is rarely achieved by chasing opportunities and avoiding challenges. Instead, it requires creating a financial plan and a resilient portfolio prescribed by that plan to transform setbacks into opportunities.

Catching the Comeback

Today, most people view Apple as a rousing success—both as an investment and as an innovator. But this doesn’t mean the business has not suffered its share of setbacks. For instance, consider the Newton, the Lisa, and the Pippin: devices that each presented a litany of faults, or perhaps ideas that were simply ahead of their time.

Yet companies, like people, should not be defined solely by their setbacks. And neither should investments. Many of us are familiar with the standard legal disclaimer used in investment advertisements: Past success does not guarantee future results. But the opposite is true as well. Past failures are not certain to be repeated.

According to a savings.com survey, 45 percent of parents with adult children provide financial support for at least one child, regardless of whether the child lives at home. Many of these parents are making significant sacrifices to help their children. They’re buying investment properties for their kids to rent at prices below market rates, withdrawing money from savings accounts to cover unexpected bills, and sending monthly allowances to help repay student loans.

The danger for some parents is that as their bank accounts dwindle, so do their chances of a secure retirement. In fact, the same study found that parents who are in the final decade before retirement are now providing the highest amount to their children—about $2,100 a month. The result: They’re depositing only $643 a month into their retirement accounts.

“As financial advisors—and fellow parents—it’s not our job to judge people for the way they spend their money,” says Joe Scarpo, a CAPTRUST financial advisor in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. “After all, it feels good to be able to provide for your kids. But if parents are risking their own financial health, it’s time to have an honest conversation.”

When Scarpo sees a client making poor financial decisions to support an adult child, “I try to explain to them, ‘It’s your choice if you want to continue allowing this. Just remember that if you go broke, then your kids will go broke too, because you’re helping them live a lifestyle they can’t really afford.’”

Breaking the Habit

If you’re a parent who has been providing regular financial assistance to adult children, the first step is to pause, step back, and ask yourself why. While the obvious answer might be because you love your children, for many it goes deeper than that.

Typically, the root cause lies in a parent’s own financial upbringing. Early money memories shape each person’s subconscious and emotional responses to financial decision-making. Many parents want to make things easier for their kids, helping them overcome small financial obstacles so they can go further in life. Others believe that providing lifelong financial support is simply a part of the job.

A 2021 research study from Stanford University, led by Associate Professor Jelena Obradović, showed that parents often assume their help will create better outcomes.

But in fact, parental involvement can be counterproductive, interfering with the child’s ability to practice self-regulation skills and build independence.

Once you have a grasp on why you want to support your adult children financially, you can make a more conscious decision about how to move forward.

This starts by taking a fresh look at your own financial picture. While there’s no specific age when children age out of needing financial support, there are thresholds beyond which parents might be putting their own financial goals at risk.

Understanding how much and how often you can give means considering factors like your retirement age, expected retirement income, lifestyle, and philanthropic intent. In the same way you might anticipate early retirement, extra healthcare expenses, or a market pullback in retirement in your financial plan, your financial advisor can help you model different giving scenarios.

This provides you with a more complete view of how gifts to your children can impact your future. Then you can adjust as needed. It also gives you guardrails to work within or may help you understand if you need to break the habit altogether.

Space to Grow

After years of help, some adult children develop a sense of entitlement to family money. Some may even believe they are not capable of solving financial problems on their own. As a parent, weaning them off support means resetting expectations for your relationship with each other and reteaching skills for financial independence.

Think of this process as tending a garden. By pulling out the weeds of entitlement, you create more space for good things to grow, including gratitude and independence. Over time, children learn how to cultivate their own financial wellness.

Here are a few first steps parents can take to reinforce financial lessons, build financial independence, and uproot entitlement in their adult children.

Tell financial stories. Talking about money can be uncomfortable. Even if you don’t want to share specific numbers, like your net worth or salary, personal anecdotes can help teach the importance of hard work, persistence, and frugality. Tell your children about some of the financial decisions you’ve made and the reasoning behind them. When did you start saving and investing? How much debt do you have? Did you get an inheritance from your own parents? What are some of the best—and worst—financial decisions you have made?

Acknowledge uncertainties. Make sure your children understand that your financial situation is not set in stone. Your assets, investments, and even your will could change, so they shouldn’t rely on your assets as a safety net. Instead, help them clarify their own financial goals and create steps to achieve them. Introducing your children to your financial advisor can be another helpful step, especially if you plan to leave an inheritance.

Consider trusts and family foundations. These entities can protect adult children from themselves and from others who might try to take advantage of them. Parents who are worried about an adult child’s financial behavior might want to explore trusts and family foundations as a safer way to leave behind assets while instituting limitations. Trusts can also keep money growing and reduce or eliminate estate and gift taxes.

Let them fail forward. It’s tempting to shield the people you love from their own financial missteps, but it’s important to let them experience the natural consequences of their decisions. These lessons will have a lasting impact and help shape their future relationship with money. Along the way, you can be there to offer guidance but don’t have to bear the burden financially. If you start to feel like you’re enabling bad decisions, trust your instincts and let your kids fail a little—or a lot. Mistakes are just another part of the learning process.

Other Ways to Help

Every parent-child relationship is unique, so the way that each parent chooses to support each of their children will be different. “Some people choose to help their children by giving them seed money to get started,” says Scarpo. “Others give financial help all along the way. And others choose to help their kids by making them earn everything on their own. All those people believe they’re doing the right thing for their children.”

In other words, there is no right or wrong way to help your children. But if you’re considering working extra years or dipping into retirement accounts to support them, it might be time to make a change. That way, when the time comes, you can both feel confident that they have what they need to bloom on their own.

Although Thoreau is inspirational, his actions are difficult to emulate. Most people cannot quit their jobs, give up most of their friends and possessions, and build a cabin in the woods with their bare hands.

What they can do is simplify the patterns of their lives to make things more manageable and meaningful. This is something Greg McKeown has studied extensively for more than a decade.

McKeown is a New York Times bestselling author of two books: Essentialism: The Disciplined Pursuit of Less and Effortless: Make It Easier to Do What Matters Most. He says it’s natural for people to assume that the solution to feeling overwhelmed is to escape, do less, or become more efficient. His philosophy, essentialism, rejects those options.

“Essentialism isn’t about getting more done in less time, and it doesn’t mean doing less for the sake of less,” says McKeown. “Essentialism is about getting only the right things done. It’s about making the wisest possible investment of your time and energy in order to operate at your highest point of contribution by doing only what is essential.”

Creating Alignment

The first step in becoming an essentialist is to determine your personal values and goals. Think of this as if you are writing a business plan for the next five years. Name your mission, vision, and core values. To begin, “Ask yourself, What is essential?,” McKeown says. “Then figure out what you need to say no to.”

Learning to say no strategically is a key tenet of essentialism. With almost limitless options for how to spend money and time, McKeown says it helps to remember that every choice also carries an opportunity cost. Each decision means shutting a door and making a trade-off. And that’s a good thing.

“Trade-offs are not something to ignore or avoid; they are something to embrace and explore,” says McKeown. By consciously accepting trade-offs, people can let go of nonessential distractions and focus on what truly matters to them. When there are fewer options available, it’s easier to create alignment between your daily actions and long-term goals.

This seems simple on paper, but it can be tricky in real life. For example, let’s say you’ve defined your values as family, faith, and self-care. A friend asks you to help organize a community litter pickup event on an upcoming weekend. You have nothing planned for those days. It’s a worthy cause, and volunteering is important to you. But it isn’t one of your essentials.

By saying no, you could create time to do things that better align with your essential values: taking a long walk with your grandchildren, for instance, or simply writing a letter to a friend. Or you could say yes, bring your grandchildren along, and use the physical activity that litter pickup entails as a form of exercise and self-care for the day.

How do you know which is the correct response? “If it isn’t a clear yes, then it’s a clear no,” says McKeown. In other words, follow your gut.

“Nonessentialists get excited by virtually everything and thus react to everything,” McKeown says. “But because they are so busy pursuing every opportunity and idea, they actually explore less.” Essentialists commit to deep exploration of what McKeown calls “the vital few” versus “the trivial many.”

By Design, Not Default

However, McKeown warns, because social expectations encourage busyness, multitasking, and hyperproductivity, even people who know their vital few can get distracted over time by exciting but nonessential opportunities. That’s why the next step is so important.

Essentialists don’t just commit to the essentials. They structure their daily lives around them.

“To get it right, we have to build essentialism into the design of our lives so that we make it easy for ourselves to prioritize what matters to us, instead of having somebody else decide what we will prioritize,” says McKeown. This means breaking ingrained patterns to live by design, not by default.

For McKeown, play and sleep are two key examples. While the nonessentialist often gives up play and may sacrifice a few hours of sleep to be more productive, essentialists know that play and sleep are necessary to reach their highest potential. So they set aside time each day for both.

“Routine is one of the most powerful tools for removing obstacles,” says McKeown. “Without routine, the pull of nonessential distractions will overpower us. But if we create a routine that enshrines the essentials, we will begin to execute them on autopilot.”

Regardless of what your essentials are—work, travel, fitness, time outside, improving your community, learning a new skill, or more— building your schedule around these priorities will help you keep focused and accomplish what really matters to you. “Almost everything is noise,” McKeown says. “Only a few things really matter.”

For today’s plan sponsors, retirement savings disparities between different demographic groups have become a significant concern.

According to the National Institute on Retirement, White employees are significantly more likely to have access to an employer-sponsored retirement plan than their racially diverse counterparts. And those who do have access end up saving roughly four times as much money for retirement. People of Latin American descent are the most likely to be left behind.

A separate report published by the U.S. Government Accountability Office shows that women contribute an average 30 percent less to their retirement accounts than men do. And for women of color, the disparity is even more pronounced.

Black Americans are also less likely to have the same earning and spending power as their White colleagues, which further affects their lifelong ability to save enough for retirement.

Moreover, it seems savings behavior has a significant impact on a person’s sense of financial wellness. So, people with less access to retirement savings vehicles or less money to save also tend to have lower financial wellness scores. A survey conducted by Greenwald and Associates investigated this connection. Of White employees with access to a workplace retirement savings plan, approximately 10 percent had financial wellness scores that needed attention. Among Latino employees, the number doubled. And among Black employees, it more than tripled. These disparities can feel alarming, and certainly, they will require consistent commitment to overcome. However, there is some good news. Over the past few years, plan sponsors have found new ways to level the playing field when it comes to retirement savings. And for today’s workforce—the most diverse in American history—change cannot come fast enough.

Evaluate Financial Needs for Your Workforce

Many employers want to craft benefit packages that account for a wide range of employee needs, desires, and demographics. And for good reason. Today, five generations of people from various cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds are working side by side. This includes baby boomers and Gen Z. Born between 1997 and 2012, Gen Z is the most racially diverse American age group ever. Figure One illustrates the racial breakdown of the American workforce by generation.

Figure One: The U.S. Workforce Is Becoming More Diverse

For employers looking to establish more inclusive benefit packages, one of the first things to consider is analyzing existing workforce demographics, says CAPTRUST Financial Advisor Mike Webb.

“A needs assessment can help plan sponsors determine which benefits and features may best meet the needs of a diverse range of employees,” says Webb. These assessments usually include questions that try to discern employee perceptions of current benefit packages. For example, an initial survey might ask: Are you aware of the company’s financial wellness and advice program? Are there additional retirement benefits you’d like to see the company offer? And, if you do not participate in the company’s retirement plan, please tell us why.

Many organizations use a combination of organization-wide surveys, listening sessions, and participant data from recordkeepers to assess usage trends by demographic groups. Recordkeeper data can help plan sponsors understand variations in plan use by age group, gender, and racial identity. Depending on the depth of data available, it may also help tease out differences between employees of different socioeconomic origins, education histories, disabilities, veteran statuses, family structures, and more.

Another option for employers is to review how employees are using current financial wellness programs, then look for usage gaps. Knowing how often a particular benefit is being used, by whom, and to what extent can help inform necessary changes. For instance, if participants are asking frequent questions about healthcare spending, the employer might consider offering a health savings account, also known as an HSA.

Design for Inclusion

Although every employer and plan will be unique, there are a few common features that have been proven to reduce retirement savings and financial wellness gaps between demographic groups. Webb says many employers start by focusing on plan design features that benefit women and people of color by encouraging retirement savings.

“Specifically, I’d say there’s strong data to show the positive impact of auto-enrollment and auto-escalation features,” Webb says. Auto-enrollment is particularly effective for low-income workers of color. According to a recent Vanguard study, when offered only voluntary enrollment, Black and Hispanic workers participate in a defined contribution plan at 35 percent and 36 percent respectively. But with auto-enrollment, participation jumps all the way to 93 percent and 94 percent.

Coupling auto-enrollment with auto-escalation can move the needle even farther. Because auto-escalation increases the default deferral amount each year, up to a predetermined maximum, “it can help mitigate demographic differences in savings rates over time,” Webb says.

Employers may also want to reexamine loan provisions and lending policies. According to the U.S. Government Accountability Office, 401(k) plans that offer loans have higher participation rates, and their participants tend to contribute more.

Furthermore, research shows that extending the allowed period when a terminated employee is allowed to repay their loan may improve overall retirement savings. “Instead of requiring departing employees to pay off loans within 60 days of termination, they could be given a longer time, perhaps up to six months,” Webb says.

Some plan sponsors also use stretch matches to encourage higher savings rates. With a stretch match, employers withhold the full amount of their matching contribution until employees reach a certain savings threshold, which is typically higher than the employee average. Those who do not save to this threshold do not receive the full match. However, determining the right threshold is key because participants who do not have the ability to save to a higher threshold may fall farther behind.

For plans with vesting schedules, sponsors may want to consider shortening vesting periods to allow more widespread access to employer contributions. Another option is to allow for immediate eligibility.

Reap the Benefits

Providing financial wellness support that is inclusive of various backgrounds, genders, ages, sexual orientations, cultures, and religions can also help to leveling the playing field, Webb says. “Employers who prioritize inclusion and diversity in their financial wellness offerings are the most likely to attract and retain candidates with a variety of perspectives and knowledge of diverse markets.”

Moreover, a study from Boston Consulting Group found the revenues of companies that attract and retain a diverse workforce were 19 percent higher than those of companies that didn’t prioritize diversity. Financial wellness programs can go a long way toward helping people feel welcome, respected, and empowered at work. But only if those programs account for their individual differences and use an inclusive lens when viewing each worker’s unique financial picture.

When considering financial wellness services from multiple vendors, plan sponsors should consider asking specifically about each firm’s perspective on diversity and inclusion and whether its frontline workers have received ample training on these topics. Relationships with money change by culture, and so, providing personalized advice means understanding cultural influence. But it also means staying sensitive to individual differences within those cultures.

Today’s retirement savings playing field is certainly uneven. But it can also be leveled. While there is no quick fix in place, evaluating the identities and financial needs of employees, finding gaps in current offerings, and working to address them are three great first steps.

Battlefields to Ballfields (B2B) is a nonprofit organization Pereira founded with his sister in 2016 to address two problems he is passionate about: the plight of many veterans and the ongoing dearth of sports officials.

B2B provides scholarships for former members of the military to train as officiants for youth sports leagues, where referees and umpires are in short supply. Recruiting quality officiants has been especially challenging in recent years, in large part due to the negativity that sports officiants often face from spectators.

“I’ve been involved in officiating practically my entire life, and I can tell you, this shortage is nationwide,” says Pereira. As older officials retire and few young people join the field, school sports in many districts have been forced to schedule fewer games, eliminate intramural and junior varsity teams, or eliminate some sports altogether.

Being a referee requires thick skin, plus a number of hard-to-teach qualities, including communication, commitment, teamwork, courage, and an unwavering sense of mission.

“These are characteristics most veterans already have and that make them good candidates for officiants,” says Pereira. “The intangibles have already been taught.” Knowing that many veterans have a hard time finding their place as civilians, Pereira felt strongly that each problem offered a solution for the other.

Watch this VESTED Voices video featuring Mike Pereira to learn what inspired him to launch Battlefields to Ballfields and how he hopes it will grow in the future.

Healing with Purpose

B2B was a lifeline for Jamaison Pilgreen, a U.S. Army veteran who served for 18 years, including six tours of duty in Afghanistan and Iraq. Pilgreen’s story of trying to cope with life after retirement is all too familiar.

Pilgreen wrestled with post-traumatic stress, depression, and unstable employment, and he was self-medicating with pain prescriptions and alcohol. He felt little hope until the day he learned about B2B. The organization offered him help but also needed his help. He jumped at the chance to participate and soon received a B2B scholarship. This included a uniform starter kit, money for local officiating dues, and membership in the National Association of Sports Officials, through which officiants can receive comprehensive liability insurance.

Pilgreen says his military training equipped him well for the role, which requires split-second judgment, coolness under pressure, an eye for detail, and the ability to take complex situations in stride. He also says working with young people gave him a sense of purpose and drive that was instrumental in helping him heal and rebuild his life in a productive way.

Passion Meets Business

Stories like Pilgreen’s fuel Pereira’s drive for his work. He says founding B2B was part passion project, part small business. “It started out with just me and my sister,” says Pereira. One of their first steps was hiring a web designer to create a website with an online application.

“The day we launched the website, we sat in anticipation. Would anyone apply?” says Pereira. “The first day, no one did. Day two, nothing again! But on day three, we got our first applicant, and we were euphoric.”

A few weeks later, someone in Sacramento heard about the scholarships, and things began to take off. “I did an interview on the local sports news telecast, and almost immediately, we got 10 more applications,” he says.

One applicant came from Omaha, Nebraska. “The newspaper in Omaha did a story on it, and the story got picked up by The Military Times,” says Pereira. After that, applications flowed in at a rate of 30 per day.

“It overwhelmed my sister and me administratively and financially,” he says. “We hadn’t expected such a big response. So then we had our first Sacramento golf tournament to fundraise.”

Later, the brother-sister duo was joined by their first volunteer, Melissa Washington, who now serves as B2B’s executive director. “Today, the two of us are running it together, after my sister moved away,” says Pereira. “We work out of our homes. We want every dollar we raise to go toward the scholarships, the vets’ officiant uniforms, dues, background checks, and so on.”

To date, B2B has awarded 900 three-year scholarships for vets to be trained as officiants. “We have 400 active participants right now, and we want 1,000 as a next step,” says Pereira. “After three years, our hope is that they continue officiating, although at that point, they no longer receive financial support from B2B.”

The organization continues to grow, now guided by a board of directors that includes people who are experienced in business, military service, and officiating. “We restructured our board and have a finance committee now,” says Pereira. “Today, I met with a tech organization that will allow us to track everything in real time and respond very quickly to our applicants.”

Launch Your Own

If there is a cause that is close to your heart, starting a nonprofit is one way to make it part of the legacy you’ll leave behind. Like starting a small business, one of the first exploratory steps is to do market research to find out what similar efforts are already underway in your area.

“At a nonprofit, everything you do is a labor of love,” says Pereira. “It may be hard, but it doesn’t feel like a burden because you’re doing something that makes some part of life a little bit better. The beauty of Battlefields to Ballfields is that it connects veterans who are looking to serve again with kids and communities, and each does the other good.”

However, unlike with a for-profit company, other organizations you find that share your goals aren’t necessarily going to be competitors. Instead, these like-minded organizations could offer you a route to volunteering, serving on a board, or working on initiatives that further your common objective.

When considering whether to launch your own nonprofit organization, here are four key questions to consider from the National Council of Nonprofits:

- What problems will the nonprofit solve?

- Who will it serve?

- Are there similar nonprofits fulfilling the same needs? Are they financially stable?

- What will make your nonprofit different and better?

If you find that a demonstrated need exists for your idea, the next step would be to consider who might join your initial board of directors. A board of directors is legally required and will typically consist of three members, though specific rules vary by state.

Choose people who are as passionate as you are, since these individuals will be instrumental in crafting your organization’s mission statement, recruiting volunteers, and fundraising for your cause. Board members should be energetic and committed to do the heavy lifting of creating a business plan, registering the nonprofit, and filing the articles of incorporation. These same people will be responsible for opening a bank account, applying for insurance, and filing with the IRS for tax-exempt status.

Like small businesses, nonprofit organizations are typically created under state law. To find resources specific to your state, visit the website for the National Council of Nonprofits, and click on the map to find your state association. In California, for example, the basic steps for starting a nonprofit include selecting a suitable name, filing articles of incorporation, appointing a board of directors, and drafting the bylaws of the organization, according to the California Association of Nonprofits.

After that, the board must officially adopt the bylaws, set the number of directors, adopt a fiscal year, and establish a bank account. For tax purposes, an officer of the organization can apply online to get an employer identification number (EIN).

Once incorporated, the next step is to apply to become a 501(c)(3), a type of nonprofit that is tax-exempt under IRS rules because of its charitable programs and initiatives. On an ongoing basis, organizations must continually stay on top of required tax filings and compliance.

While there is a lot of work involved in founding a nonprofit, the reward lies in knowing that your contributions can live on as part of your legacy through the organization’s programs and initiatives.

“I love my job, but it’s not even a comparison as to how you feel when you influence someone in a positive way like this,” says Pereira. “People deny it, but really, we all think about what our legacies will be. If you go on my Wikipedia page and read the section about when I was working for the NFL, it says I changed the officials’ uniforms from white knickers to long white pants. That’s not what I want my legacy to be. I want to know that I made a difference in people’s lives.”

Additional Resources for Launching a Nonprofit

- State-by-state resources from the National Council of Nonprofits

- National Association of State Charity Officials

- Information on choosing your board of directors

- IRS information on gaining tax-exempt status

As the retirement plan landscape has evolved, so have the investment menu options offered to participants. The Pension Protection Act of 2006 (PPA) marked a turning point in this history, creating a path to plan sponsor safe harbor regarding automatic features and qualified default investment alternatives (QDIAs). After the passage of PPA, DC plan investment menus expanded exponentially. Now the industry is seeing a trend toward condensed lineups as plan sponsors learn to craft more thoughtful menus that still allow for customization with fewer investment vehicles. While the lineup of the past centered around participant choice, the lineup of the future will likely center around participant needs.

“The key pieces of any DC plan menu are the QDIA and the core lineup,” says Peter Ruffel, a manager in CAPTRUST’s defined contribution practice. “The QDIA provides a prudent, diversified option for less engaged participants, and the core lineup lets more engaged employees cater to their own risk and time horizon needs.”

Section 404(c) of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) provides a safe harbor for fiduciaries related to participants’ investment actions. One of the requirements of 404(c) is to offer a broad range of investment options consisting of at least three diversified fund options. But the average plan typically offers much more than that.

According to the Plan Sponsor Council of America’s (PSCA) 65th Annual Survey of Proft-Sharing and 401(k) Plans, the average 401(k) plan now offers 21 investment options. “This is down from the average of 25-30 funds we were seeing a decade ago,” says Ruffel. By providing so many investment choices, sponsors were hoping to invite customization, yet many funds saw minimal uptake.

“There is no right or wrong number of investment options,” says John Hays, a manager in CAPTRUST’s defined contribution practice. “In fact, there are studies on both sides of the debate that seem to present conflicting results.” Some say too many funds can create negative outcomes. Others say that, with additional options, participants will diversify more.

In other words, although there is a trend toward condensed menus, fewer does not necessarily mean better. “There are a lot of right ways to build a DC investment menu,” says Ruffel. “What matters is that investment lineups are aligned with participant needs.”

Thoughtful Responses

Designing the optimal investment menu to meet participant needs requires being both proactive and flexible. For example, market conditions or industry trends may influence sponsors to pursue reactive menu changes, like adding multiple bond portfolios to balance stock market declines.

“Sometimes, sponsors need to react quickly, but they also need to think through the potential inertia of reactive decisions to make sure they can effectively unwind things if unwinding becomes necessary,” says Hays.

Ruffel points to the global financial crisis of 2008 and 2009. In the years following, many asset managers were touting low-volatility investment products that appealed to people’s desire for security and stability. “In the wake of chaos, low volatility sounds comforting, but as the market improved, those investors missed out on a significant amount of growth,” he says.

When evaluating reactive moves in response to market volatility, economic headwinds, or inflation, plan sponsors should consider whether each new investment will still be prudent and desirable as the market and economy evolve. Investment performance is likely to fluctuate but should meet a baseline of growth to continue earning its spot on the plan’s investment menu.

Trend following is another area where sponsors would do well to balance reactivity with a long-term view. Benchmarking investment menus against industry standards is a recommended practice, but deciding which trends to follow—and which ones may not be a good fit—will depend on each sponsor’s unique participant base. For example, a manufacturing company with 5,000 working-class employees will need to meet very different investor needs than a healthcare organization of 200 highly compensated surgeons.

“The question to ask is: ‘Will this actually benefit my participants’ accounts?’” says Hays. “The answer will depend on the organization’s goals and objectives, employee demographics, and existing participant usage data.”

It’s also important to remember that not all trends will be relevant for all organizations. “Benchmarking can’t tell you what to do,” says Ruffel. “It just helps you understand what other people are doing.” Most organizations want to be evolutionary over time—not revolutionary.”

However, some sponsors will need to break with industry trends to meet participant needs. In that case, Ruffel says, “Documenting the process you’ve used to make that decision can be just as important as the decision made.”

Another way to fine-tune investment menus is by analyzing participant behavior. “Usage data can be a good starting point when making decisions about paring things down or adding new options,” says Hays. “A low participant count or low asset total can be a strong indicator that an offering may not be meeting participant needs.” By tuning in to data, sponsors can make informed changes.

Pushing Ahead of the Pack

Proactive changes are equally important. Recently, Ruffel and Hays say they have witnessed an increase in conversations about retirement income solutions, a sustained interest in managed accounts, and detailed questions about the benefits of dynamic QDIAs, also called dual QDIAs.

Although sponsors are interested in learning more about decumulation strategies and through-retirement glidepaths for participants, Ruffel says that most plan sponsors are still early in their journeys toward providing total retirement income solutions. “Many sponsors are already offering target-date funds designed to manage assets through retirement, sometimes up to 30 years.” According to CAPTRUST data, 87 percent of 401(k) plan sponsors use target-date funds as part of their investment menus, and nearly 47 percent of total participant assets are allocated to these funds.

“Now, some sponsors are exploring evolved target-date strategies with a built-in retirement income feature or annuity option that can provide participants with a steady stream of income during retirement,” Ruffel says, but this is still a very small percentage of plans.

Although target-date funds are now an essential part of designing a DC menu, they are still a relatively recent development. “Before the PPA, it was a novel idea to use target-date funds in a retirement plan,” says Ruffel. “PSCA didn’t even start surveying plan sponsors on the use of these funds until 2012. That means there are almost certainly other aspects of menu design that we’re talking about today as proactive or future-focused but that, in 10 years, will be expected table stakes.” Managed accounts are one investment solution likely to make that list.

Ruffel and Hays anticipate an increase in managed accounts going forward. These are accounts owned by individual investors but managed by a professional investment manager that makes discretionary decisions on the investor’s behalf. Now easier than ever for participants to use and access, managed accounts allow participants to have personalized portfolios built using their individual financial situation and goals. This can be especially useful as the participant approaches retirement.

“However, these accounts may not be right for everyone,” says Hays. “For participants in their 20s and 30s, a target-date fund may be more appropriate. But for those who are 10 or 20 years from retirement, a managed account can be a helpful option to help them reach their personal retirement goals.” Hays says one important piece to consider is cost relative to the value and services received.

Plan sponsors who want to combine the benefits of target-date funds with managed accounts may choose to explore a new generation of QDIAs: those that utilize target-date funds for younger participants, but transition to managed accounts as participants approach retirement.

These dynamic or dual QDIAs can automatically adjust participants’ investment allocations based on factors beyond just age and market conditions. Instead, they look at salary, account balance, pension or other savings plans, savings rates, sponsor match, and more to provide a more tailored investment experience across the participant’s lifespan. Typically, participants will be transitioned into a managed account at a specified age when additional factors outside of risk and retirement horizon can be impactful to a tailored asset allocation.

This means even disengaged participants can receive personalized advice to optimize their retirement savings. And the more engaged participants are, the more customized the portfolios can become by adding assets outside the retirement plan and specific investment goals and objectives.

The Investment Lineup of the Future

As part of their fiduciary responsibility, plan sponsors should revisit investment menus periodically. “Otherwise, it’s easy to get stuck in the habit of scoring each underlying investment and its performance outcome only, without taking a 10,000-foot view of the lineup itself,” says Ruffel.

When evaluating which investments to add or subtract, the following questions can be helpful:

- Which investment options have the lowest engagement, either by number of participants or by total assets? Where are new contributions going?

- Do any pieces of the menu overlap with each other?

- Is the menu overly focused on one asset class or investment area?

- Are there any gaps that an additional offering could help to fill?

- What are other plan sponsors doing?

- Is a self-directed brokerage account (SDBA) option available to participants? If so, what investment options are available to them through that service?

Although the investment menus of the future will vary by sponsor, it seems increasingly likely that their core purpose will be to home in on and provide for diverse participant needs. The next decade of this evolution will likely involve a rapid development of tools, services, and products that nudge participants in the right direction in terms of how they are saving, how much they are saving, and—when they are finished saving—how they can withdraw money from the plan.

As data-analysis and money-management technologies converge, plan sponsors will be able to make better reactive and proactive decisions, informed by both internal and external data. But they’re also likely to be reminded that investment menus are only one piece of the puzzle.

“A big part of retiring well means feeling confident in your retirement savings,” says Ruffel. “Sometimes, that’s not about investments at all. It’s about tools, resources, and education. The investment menu isn’t everything. It’s just one component.”

Hays agrees. “A huge part of this has nothing to do with the plan lineup in and of itself. It has more to do with the participants’ ability to understand the lineup, use it well, and feel confident in it, so that they don’t make knee-jerk reactions every time the market declines or the economy contracts.”

Adapting to meet participant needs goes far beyond the design of retirement plan menus. It’s a shift in mindset that is likely to sweep across the broad swath of employee benefits, from financial wellness and advice programs, to health savings accounts and retirement plan design changes that can help employees pay for college and meet emergency needs.

As a lawyer advising sponsors of employee benefit plans that are subject to the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA), I am often asked to help address questions of fiduciary governance. Over the years, I have learned that identifying plan decision-makers and assigning fiduciary responsibilities—which is the heart of good fiduciary governance—requires a robust understanding of both the culture of that organization and the people who drive it.

Put simply, in order for legal best practices to actually reduce liability, increase efficiency, and encourage (or at least not stifle) innovation, the fiduciary structure put in place has to work with the organization, not against it.

In connection with fiduciary governance, I am frequently asked whether it is better for a plan sponsor to hire a third-party fiduciary to advise on plan investment or to manage those investments directly. These two types of fiduciary relationships are often described using shorthand versions of statutory citations. A 3(21) fiduciary is an investment advisor and 3(38) fiduciary is an investment manager.

Below, I briefly outline the legal differences and similarities of these two approaches and discuss some additional considerations relevant to selecting an investment fiduciary for your company’s retirement plan.

What the Numbers Mean

While it is common to label fiduciaries who provide advice as 3(21) fiduciaries and those who exercise investment discretion as 3(38) fiduciaries, both types of fiduciaries are actually described in section 3(21) of ERISA. This section defines a fiduciary as both:

- a person who has or exercises discretionary authority over the assets or administration of the plan (that is, the actual decisionmakers); and

- a person who provides investment advice for a fee with respect to the assets of the plan (that is, people who are not decision-makers but who recommend investments to decisionmakers).

One important distinction between the two types of fiduciaries is that they do different things—one advises a plan decisionmaker, and the other is the plan decisionmaker.

Another distinction arises from the way ERISA apportions legal liability. ERISA permits a named fiduciary to appoint an investment manager (as defined in section 3(38) of ERISA) to manage plan assets. This investment manager must be a discretionary fiduciary who is also registered as an investment advisor, is a bank or insurance company, and who has acknowledged in writing that it is a fiduciary with respect to the plan.

The appointment of an investment manager is advantageous for the named fiduciary because it relieves them and the plan’s trustee of fiduciary responsibilities for the investment of all assets that are under management of the investment manager, and for the manager’s acts or omissions in doing so. However, as discussed below, knowing the differences does not end the analysis.

There Is No Right Answer

While the additional liability relief that comes along with the appointment of a named fiduciary can be important, the specific needs of the plan and the services that the fiduciary is expected to provide are critical to the selection decision. For instance, appointing a 3(38) investment manager won’t be effective to relieve the appointing fiduciary of liability, unless the manager is actually given the power to manage the plan’s assets.

Any person who provides advice to a plan but does not exercise investment discretion is a fiduciary by reason of providing investment advice but is not considered that plan’s investment manager, regardless of how the parties decide to privately characterize their relationship). Status as an ERISA investment manager is functional. It is possible that certain activities such as monitoring of investment options and performance reporting may not be viewed as part of that fiduciary’s power to manage assets and thus not viewed as investment manager responsibilities.

Additionally, while fiduciary advisors and discretionary investment managers have different roles, the standards of care and loyalty that are imposed by ERISA on the two types of fiduciaries are identical—and exacting. For instance, each type of fiduciary must act in accordance with ERISA’s prudent expert standard and must avoid prohibited transactions.

And the plan sponsor that is appointing an investment manager or hiring a fiduciary advisor must monitor the fiduciary to ensure that the plan’s needs continue to be met.

In my practice, I find that like any other fiduciary governance decision, deciding how to structure a plan’s relationship with an outside fiduciary works best if informed by both legal and practical considerations. In selecting an outside fiduciary, the plan sponsor should understand the legal differences and similarities between 3(21) and 3(38) fiduciaries. But they must also consider the particular needs of the plan, its participants best interests, and the plan’s existing fiduciary governance structure.

When donors give money to nonprofit organizations, they typically do not expect a tangible product or service in return. What they do expect is responsible governance. In fact, research shows that donor confidence relies directly on an organization’s governance practices. Specifically, major donations and government grants strongly correlate with formal written policies, independent audits, board independence, and accessible financial information, according to a study from The Accounting Review.

Although there is no one-size-fits-all formula for effective governance, time and experience have revealed a common set of practices that may improve board efficiency and effectiveness, thereby increasing donors’ confidence in the organization. Transparency, for instance, is especially important, with astute donors relying on sources such as Charity Navigator to assess an organization’s fiduciary management, governance practices, and administrative costs. This article explores four additional best practices for nonprofit governance that can improve fundraising outcomes by increasing donor confidence.

Committee Overlap

Consider overlapping committee members. Organizations that consider finance and investment committee perspectives when they are making governance decisions typically experience better alignment between spending, fundraising, and investing. “However, we still see plenty of organizations with investment committees that are operating separately from their finance and development committees,” says Heather Shanahan, CAPTRUST director of endowments and foundations.

“This is not a recommended practice,” says Shanahan. “When committees are siloed, it means people with insight into the organization’s investment objectives—and its outcomes—are not participating in spending decisions, and vice versa.”

“The disconnect can create significant potential for declining asset values,” says CAPTRUST Senior Director Grant Verhaeghe. To mitigate this risk, many organizations create a unified finance committee that handles budgets, investments, fundraising, and spending. Others choose to keep committees separate but create overlap through governance structures, for instance via regular finance meetings that include at least one member from each related committee.

“Ideally, spending decisions will be tied to asset performance, and multiple board members will take part in discussions about both,” says Verhaeghe. When everyone has at least a basic understanding of the organization’s assets, investment goals, current spending, and budget limitations, the board can make more informed decisions. This includes decisions related to fundraising, debt, and development. Regardless of how the organization chooses to do things, clear and frequent communication is key because it helps ensure alignment between financial objectives and results.

Continuity Through Documentation

Robust documentation is another best practice that may improve fundraising outcomes by demonstrating trustworthiness. And it’s especially important considering board member turnover.

CAPTRUST Vice President and Financial Advisor Will Chitwood says he has seen a significant uptick in board turnover since the pandemic, attributing the trend, in part, to exhaustion and burnout over that time. “We’ve witnessed board member turnover varying from regular, predictable succession to organizations that are in the process of transitioning their entire boards,” says Chitwood. “Some of that turnover was expected for board members with longer tenures. But some was certainly a surprise.”