-

Solutions

- Solutions

-

Individuals & Families

- Individuals & Families

- Individual Investors

- Executives & Business Owners

- Families with Complex Needs

- Professional Athletes

-

Retirement Plan Sponsors

- Retirement Plan Sponsors

- Corporations

- Educational Institutions

- Healthcare Organizations

- Nonprofits

- Government Entities

- Endowment & Foundation Leaders

- See All Solutions

Comprehensive wealth planning and investment advice, tailored to your unique needs and goals.Investment advisory and co-fiduciary services that help you deliver more effective total retirement solutions.CAPTRUST provides investment, fiduciary, and risk management services for nonprofit organizations. -

About Us

- About Us

- Our People

- Our Story

- Learn About CAPTRUST

-

Locations

-

Resources

- Resources

- Articles

- Podcasts

- Videos

- Webinars

- See All Resources

Although Thoreau is inspirational, his actions are difficult to emulate. Most people cannot quit their jobs, give up most of their friends and possessions, and build a cabin in the woods with their bare hands.

What they can do is simplify the patterns of their lives to make things more manageable and meaningful. This is something Greg McKeown has studied extensively for more than a decade.

McKeown is a New York Times bestselling author of two books: Essentialism: The Disciplined Pursuit of Less and Effortless: Make It Easier to Do What Matters Most. He says it’s natural for people to assume that the solution to feeling overwhelmed is to escape, do less, or become more efficient. His philosophy, essentialism, rejects those options.

“Essentialism isn’t about getting more done in less time, and it doesn’t mean doing less for the sake of less,” says McKeown. “Essentialism is about getting only the right things done. It’s about making the wisest possible investment of your time and energy in order to operate at your highest point of contribution by doing only what is essential.”

Creating Alignment

The first step in becoming an essentialist is to determine your personal values and goals. Think of this as if you are writing a business plan for the next five years. Name your mission, vision, and core values. To begin, “Ask yourself, What is essential?,” McKeown says. “Then figure out what you need to say no to.”

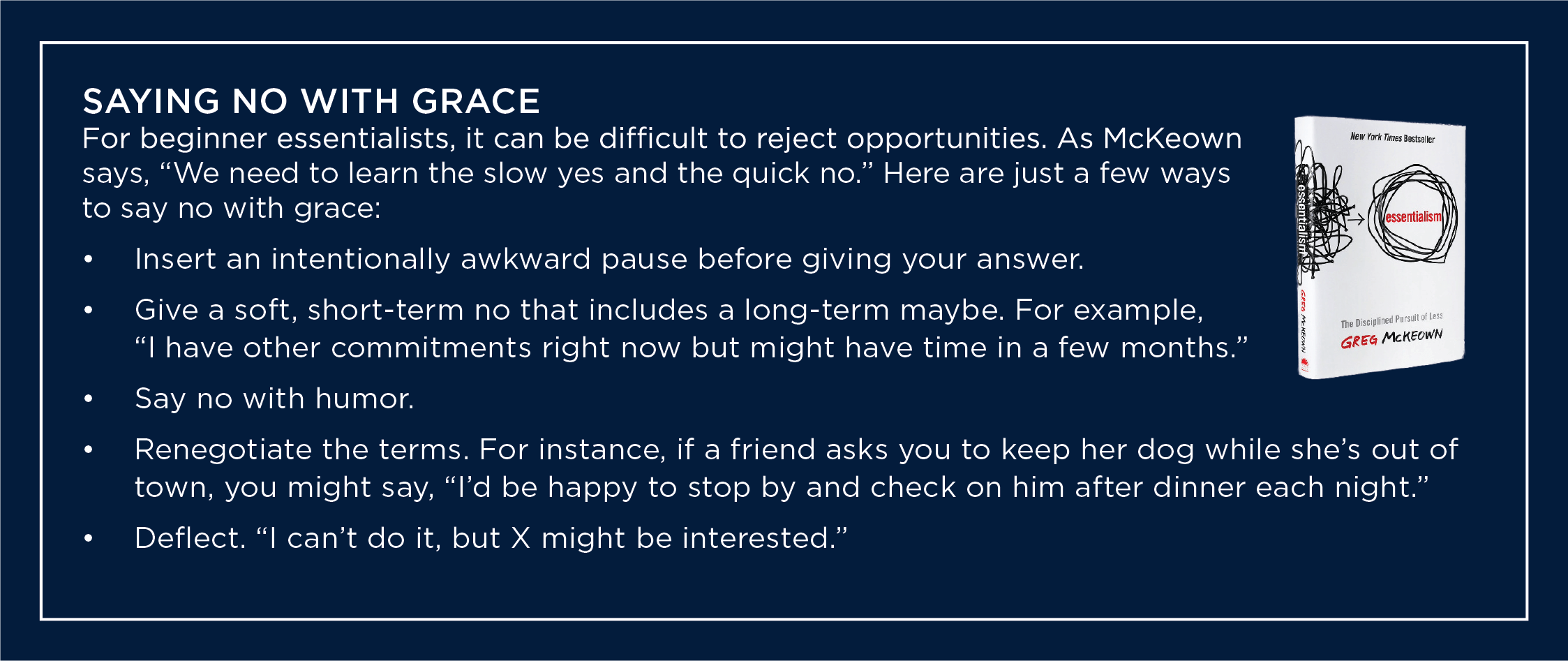

Learning to say no strategically is a key tenet of essentialism. With almost limitless options for how to spend money and time, McKeown says it helps to remember that every choice also carries an opportunity cost. Each decision means shutting a door and making a trade-off. And that’s a good thing.

“Trade-offs are not something to ignore or avoid; they are something to embrace and explore,” says McKeown. By consciously accepting trade-offs, people can let go of nonessential distractions and focus on what truly matters to them. When there are fewer options available, it’s easier to create alignment between your daily actions and long-term goals.

This seems simple on paper, but it can be tricky in real life. For example, let’s say you’ve defined your values as family, faith, and self-care. A friend asks you to help organize a community litter pickup event on an upcoming weekend. You have nothing planned for those days. It’s a worthy cause, and volunteering is important to you. But it isn’t one of your essentials.

By saying no, you could create time to do things that better align with your essential values: taking a long walk with your grandchildren, for instance, or simply writing a letter to a friend. Or you could say yes, bring your grandchildren along, and use the physical activity that litter pickup entails as a form of exercise and self-care for the day.

How do you know which is the correct response? “If it isn’t a clear yes, then it’s a clear no,” says McKeown. In other words, follow your gut.

“Nonessentialists get excited by virtually everything and thus react to everything,” McKeown says. “But because they are so busy pursuing every opportunity and idea, they actually explore less.” Essentialists commit to deep exploration of what McKeown calls “the vital few” versus “the trivial many.”

By Design, Not Default

However, McKeown warns, because social expectations encourage busyness, multitasking, and hyperproductivity, even people who know their vital few can get distracted over time by exciting but nonessential opportunities. That’s why the next step is so important.

Essentialists don’t just commit to the essentials. They structure their daily lives around them.

“To get it right, we have to build essentialism into the design of our lives so that we make it easy for ourselves to prioritize what matters to us, instead of having somebody else decide what we will prioritize,” says McKeown. This means breaking ingrained patterns to live by design, not by default.

For McKeown, play and sleep are two key examples. While the nonessentialist often gives up play and may sacrifice a few hours of sleep to be more productive, essentialists know that play and sleep are necessary to reach their highest potential. So they set aside time each day for both.

“Routine is one of the most powerful tools for removing obstacles,” says McKeown. “Without routine, the pull of nonessential distractions will overpower us. But if we create a routine that enshrines the essentials, we will begin to execute them on autopilot.”

Regardless of what your essentials are—work, travel, fitness, time outside, improving your community, learning a new skill, or more— building your schedule around these priorities will help you keep focused and accomplish what really matters to you. “Almost everything is noise,” McKeown says. “Only a few things really matter.”

For today’s plan sponsors, retirement savings disparities between different demographic groups have become a significant concern.

According to the National Institute on Retirement, White employees are significantly more likely to have access to an employer-sponsored retirement plan than their racially diverse counterparts. And those who do have access end up saving roughly four times as much money for retirement. People of Latin American descent are the most likely to be left behind.

A separate report published by the U.S. Government Accountability Office shows that women contribute an average 30 percent less to their retirement accounts than men do. And for women of color, the disparity is even more pronounced.

Black Americans are also less likely to have the same earning and spending power as their White colleagues, which further affects their lifelong ability to save enough for retirement.

Moreover, it seems savings behavior has a significant impact on a person’s sense of financial wellness. So, people with less access to retirement savings vehicles or less money to save also tend to have lower financial wellness scores. A survey conducted by Greenwald and Associates investigated this connection. Of White employees with access to a workplace retirement savings plan, approximately 10 percent had financial wellness scores that needed attention. Among Latino employees, the number doubled. And among Black employees, it more than tripled. These disparities can feel alarming, and certainly, they will require consistent commitment to overcome. However, there is some good news. Over the past few years, plan sponsors have found new ways to level the playing field when it comes to retirement savings. And for today’s workforce—the most diverse in American history—change cannot come fast enough.

Evaluate Financial Needs for Your Workforce

Many employers want to craft benefit packages that account for a wide range of employee needs, desires, and demographics. And for good reason. Today, five generations of people from various cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds are working side by side. This includes baby boomers and Gen Z. Born between 1997 and 2012, Gen Z is the most racially diverse American age group ever. Figure One illustrates the racial breakdown of the American workforce by generation.

Figure One: The U.S. Workforce Is Becoming More Diverse

For employers looking to establish more inclusive benefit packages, one of the first things to consider is analyzing existing workforce demographics, says CAPTRUST Financial Advisor Mike Webb.

“A needs assessment can help plan sponsors determine which benefits and features may best meet the needs of a diverse range of employees,” says Webb. These assessments usually include questions that try to discern employee perceptions of current benefit packages. For example, an initial survey might ask: Are you aware of the company’s financial wellness and advice program? Are there additional retirement benefits you’d like to see the company offer? And, if you do not participate in the company’s retirement plan, please tell us why.

Many organizations use a combination of organization-wide surveys, listening sessions, and participant data from recordkeepers to assess usage trends by demographic groups. Recordkeeper data can help plan sponsors understand variations in plan use by age group, gender, and racial identity. Depending on the depth of data available, it may also help tease out differences between employees of different socioeconomic origins, education histories, disabilities, veteran statuses, family structures, and more.

Another option for employers is to review how employees are using current financial wellness programs, then look for usage gaps. Knowing how often a particular benefit is being used, by whom, and to what extent can help inform necessary changes. For instance, if participants are asking frequent questions about healthcare spending, the employer might consider offering a health savings account, also known as an HSA.

Design for Inclusion

Although every employer and plan will be unique, there are a few common features that have been proven to reduce retirement savings and financial wellness gaps between demographic groups. Webb says many employers start by focusing on plan design features that benefit women and people of color by encouraging retirement savings.

“Specifically, I’d say there’s strong data to show the positive impact of auto-enrollment and auto-escalation features,” Webb says. Auto-enrollment is particularly effective for low-income workers of color. According to a recent Vanguard study, when offered only voluntary enrollment, Black and Hispanic workers participate in a defined contribution plan at 35 percent and 36 percent respectively. But with auto-enrollment, participation jumps all the way to 93 percent and 94 percent.

Coupling auto-enrollment with auto-escalation can move the needle even farther. Because auto-escalation increases the default deferral amount each year, up to a predetermined maximum, “it can help mitigate demographic differences in savings rates over time,” Webb says.

Employers may also want to reexamine loan provisions and lending policies. According to the U.S. Government Accountability Office, 401(k) plans that offer loans have higher participation rates, and their participants tend to contribute more.

Furthermore, research shows that extending the allowed period when a terminated employee is allowed to repay their loan may improve overall retirement savings. “Instead of requiring departing employees to pay off loans within 60 days of termination, they could be given a longer time, perhaps up to six months,” Webb says.

Some plan sponsors also use stretch matches to encourage higher savings rates. With a stretch match, employers withhold the full amount of their matching contribution until employees reach a certain savings threshold, which is typically higher than the employee average. Those who do not save to this threshold do not receive the full match. However, determining the right threshold is key because participants who do not have the ability to save to a higher threshold may fall farther behind.

For plans with vesting schedules, sponsors may want to consider shortening vesting periods to allow more widespread access to employer contributions. Another option is to allow for immediate eligibility.

Reap the Benefits

Providing financial wellness support that is inclusive of various backgrounds, genders, ages, sexual orientations, cultures, and religions can also help to leveling the playing field, Webb says. “Employers who prioritize inclusion and diversity in their financial wellness offerings are the most likely to attract and retain candidates with a variety of perspectives and knowledge of diverse markets.”

Moreover, a study from Boston Consulting Group found the revenues of companies that attract and retain a diverse workforce were 19 percent higher than those of companies that didn’t prioritize diversity. Financial wellness programs can go a long way toward helping people feel welcome, respected, and empowered at work. But only if those programs account for their individual differences and use an inclusive lens when viewing each worker’s unique financial picture.

When considering financial wellness services from multiple vendors, plan sponsors should consider asking specifically about each firm’s perspective on diversity and inclusion and whether its frontline workers have received ample training on these topics. Relationships with money change by culture, and so, providing personalized advice means understanding cultural influence. But it also means staying sensitive to individual differences within those cultures.

Today’s retirement savings playing field is certainly uneven. But it can also be leveled. While there is no quick fix in place, evaluating the identities and financial needs of employees, finding gaps in current offerings, and working to address them are three great first steps.

Living longer should mean more time to spend with your loved ones, doing things you enjoy, making memories, and cementing your legacy. Not just more time juggling the chronic and progressive ailments of older age.

“One of the greatest challenges facing older adults is preventing physical disability and extending what we call ‘active life expectancy,’” says geriatric specialist Ami Hall, DO.

That is to say spending older age living life to its fullest. They call that successful aging. It’s the difference between getting older (which we all do) and getting frailer (which we don’t necessarily all do).

Your genetics play a big role in how well you age. But your genes aren’t your destiny. Fortunately, there are steps you can take throughout your life that can help you maintain your physical, mental, and cognitive health as you age. And it’s never too late to start.

Illnesses like diabetes, congestive heart failure, and some forms of dementia can be delayed or even prevented. Even loss of muscle strength with aging is at least partly preventable. And maintaining a positive outlook can help you stay mentally strong as you face illness and personal losses.

Dr. Hall shared with us advice for successful aging that can help you retain your mobility, independence, and overall well-being longer.

Maintain Your Physical Health

Your physical health is one of the most important factors of successful aging. A healthy body will allow you more opportunities to do the things you enjoy.

“A lot of people look forward to things like traveling, volunteering, or caring for their grandchildren after they retire. Those goals are going to be easier to meet and more enjoyable if your body is physically up to the task,” Dr. Hall notes. “The longer you can keep your body healthy and strong, the longer you can expect to live life on your own terms.”

Dr. Hall recommends these top tips for keeping healthy as you age:

- Avoid cigarette smoking.

- Limit your alcohol consumption to no more than one beverage per day.

- Exercise regularly, being sure to incorporate weight-training, aerobic and balance activities.

- Eat a healthy diet that limits packaged and processed foods and prioritizes plant-based foods, lean protein and healthy fats.

- Maintain a weight that’s healthy for you.

- Get enough sleep.

- Practice stress management techniques.

- Get regular medical checkups.

- Play attention to any physical limitations, such as difficulty walking or problems with balance. Seek care before issues severely affect your life.

Keep Your Mind Engaged

An important part of successful aging is keeping your brain active. In fact, the National Institute on Aging explains that keeping your brain engaged in stimulating activities may help compensate for some of the changes that lead to things like dementia and memory loss.

“I like to recommend that people try new hobbies and practice learning new skills throughout their lives,” Dr. Hall says. “In some ways, our brains are much like our muscles—the more you work it, the better your chances of keeping it strong.”

In other words, that whole “can’t-teach-old-dogs-new-tricks” thing? Forget it. Exercising your brain can help prevent cognitive decline and ward off conditions like Alzheimer’s disease.

Try these methods to boost your brain health:

- Participate regularly in hobbies that interest you.

- Try new activities and build new skills. (Maybe try playing a new instrument. Or how about chess?)

- Take part in physically active interests — like dancing, swimming, running or walking. These can keep your body active and can elevate your mood. What’s more, physical activity helps increase blood flow and oxygen to your brain to help keep you mentally sharp.

- Keep an active social life and engage regularly with others.

- Try brain-training games to challenge your mind.

- Talk with your provider about how your health conditions or medications may affect your memory or contribute to confusion.

Share Your Wishes and Goals

Working toward a goal requires some planning. And a goal to age successfully is no different.

What do you want your life to look like in your 60s, 70s, and beyond? What do you want to achieve? How do you want to be remembered?

Those are big questions. Some of the biggest ones. And you don’t need to have all the exact answers.

But knowing what you want from your life can inform how you care for yourself and how you plan for the future you want.

“Maintaining dignity in older age is important to a lot of people,” Dr. Hall explains. “Consider what you want your future to look like and work backward from there. Share your wishes with others. That way you can live with peace of mind knowing that your desires are understood.”

For example, if your goal is to age at home, as opposed to an assisted living facility, consider what modifications you’ll need to make it safe. Can you move to a first-floor bedroom if you have mobility concerns in the future? Who will help maintain your yard and your home if you’re unable to?

No one knows what their future holds. But preparing for the future you want is important to successful aging. You can start now with steps like:

- Considering what you’d like for your future living arrangements. Depending on your desires, that may mean acquiring long-term care insurance or managing investments and assets to cover costs.

- Choosing a caregiver who’s knowledgeable in the medical care of older adults, like a geriatrician.

- Communicating your care goals to your family and your healthcare provider.

- Creating an advance directive — a legally binding document that outlines your healthcare wishes if you can’t. That may also include naming a healthcare power of attorney — a person to make decisions on your behalf if needed.

Some people don’t like to think about getting older. Others look forward to their older years with gusto—as an opportunity to finally have the future they’ve worked their whole lives for. Either way, people are living longer than ever before.

And by caring for your health now, you can help make sure your older years are more active. More independent. And, frankly, more fun.

This article was originally published by the Cleveland Clinic and is republished here with permission. © July 5, 2023 Cleveland Clinic. All rights reserved. The content has not been modified and is provided for informational purposes only. Neither CAPTRUST nor Cleveland Clinic endorse or assume responsibility for any third-party websites, products, or services that may be linked or referenced herein. Cleveland Clinic is a nonprofit multispecialty academic medical center that integrates clinical and hospital care with research and education. For more information, please visit https://my.clevelandclinic.org.

Battlefields to Ballfields (B2B) is a nonprofit organization Pereira founded with his sister in 2016 to address two problems he is passionate about: the plight of many veterans and the ongoing dearth of sports officials.

B2B provides scholarships for former members of the military to train as officiants for youth sports leagues, where referees and umpires are in short supply. Recruiting quality officiants has been especially challenging in recent years, in large part due to the negativity that sports officiants often face from spectators.

“I’ve been involved in officiating practically my entire life, and I can tell you, this shortage is nationwide,” says Pereira. As older officials retire and few young people join the field, school sports in many districts have been forced to schedule fewer games, eliminate intramural and junior varsity teams, or eliminate some sports altogether.

Being a referee requires thick skin, plus a number of hard-to-teach qualities, including communication, commitment, teamwork, courage, and an unwavering sense of mission.

“These are characteristics most veterans already have and that make them good candidates for officiants,” says Pereira. “The intangibles have already been taught.” Knowing that many veterans have a hard time finding their place as civilians, Pereira felt strongly that each problem offered a solution for the other.

Watch this VESTED Voices video featuring Mike Pereira to learn what inspired him to launch Battlefields to Ballfields and how he hopes it will grow in the future.

Healing with Purpose

B2B was a lifeline for Jamaison Pilgreen, a U.S. Army veteran who served for 18 years, including six tours of duty in Afghanistan and Iraq. Pilgreen’s story of trying to cope with life after retirement is all too familiar.

Pilgreen wrestled with post-traumatic stress, depression, and unstable employment, and he was self-medicating with pain prescriptions and alcohol. He felt little hope until the day he learned about B2B. The organization offered him help but also needed his help. He jumped at the chance to participate and soon received a B2B scholarship. This included a uniform starter kit, money for local officiating dues, and membership in the National Association of Sports Officials, through which officiants can receive comprehensive liability insurance.

Pilgreen says his military training equipped him well for the role, which requires split-second judgment, coolness under pressure, an eye for detail, and the ability to take complex situations in stride. He also says working with young people gave him a sense of purpose and drive that was instrumental in helping him heal and rebuild his life in a productive way.

Passion Meets Business

Stories like Pilgreen’s fuel Pereira’s drive for his work. He says founding B2B was part passion project, part small business. “It started out with just me and my sister,” says Pereira. One of their first steps was hiring a web designer to create a website with an online application.

“The day we launched the website, we sat in anticipation. Would anyone apply?” says Pereira. “The first day, no one did. Day two, nothing again! But on day three, we got our first applicant, and we were euphoric.”

A few weeks later, someone in Sacramento heard about the scholarships, and things began to take off. “I did an interview on the local sports news telecast, and almost immediately, we got 10 more applications,” he says.

One applicant came from Omaha, Nebraska. “The newspaper in Omaha did a story on it, and the story got picked up by The Military Times,” says Pereira. After that, applications flowed in at a rate of 30 per day.

“It overwhelmed my sister and me administratively and financially,” he says. “We hadn’t expected such a big response. So then we had our first Sacramento golf tournament to fundraise.”

Later, the brother-sister duo was joined by their first volunteer, Melissa Washington, who now serves as B2B’s executive director. “Today, the two of us are running it together, after my sister moved away,” says Pereira. “We work out of our homes. We want every dollar we raise to go toward the scholarships, the vets’ officiant uniforms, dues, background checks, and so on.”

To date, B2B has awarded 900 three-year scholarships for vets to be trained as officiants. “We have 400 active participants right now, and we want 1,000 as a next step,” says Pereira. “After three years, our hope is that they continue officiating, although at that point, they no longer receive financial support from B2B.”

The organization continues to grow, now guided by a board of directors that includes people who are experienced in business, military service, and officiating. “We restructured our board and have a finance committee now,” says Pereira. “Today, I met with a tech organization that will allow us to track everything in real time and respond very quickly to our applicants.”

Launch Your Own

If there is a cause that is close to your heart, starting a nonprofit is one way to make it part of the legacy you’ll leave behind. Like starting a small business, one of the first exploratory steps is to do market research to find out what similar efforts are already underway in your area.

“At a nonprofit, everything you do is a labor of love,” says Pereira. “It may be hard, but it doesn’t feel like a burden because you’re doing something that makes some part of life a little bit better. The beauty of Battlefields to Ballfields is that it connects veterans who are looking to serve again with kids and communities, and each does the other good.”

However, unlike with a for-profit company, other organizations you find that share your goals aren’t necessarily going to be competitors. Instead, these like-minded organizations could offer you a route to volunteering, serving on a board, or working on initiatives that further your common objective.

When considering whether to launch your own nonprofit organization, here are four key questions to consider from the National Council of Nonprofits:

- What problems will the nonprofit solve?

- Who will it serve?

- Are there similar nonprofits fulfilling the same needs? Are they financially stable?

- What will make your nonprofit different and better?

If you find that a demonstrated need exists for your idea, the next step would be to consider who might join your initial board of directors. A board of directors is legally required and will typically consist of three members, though specific rules vary by state.

Choose people who are as passionate as you are, since these individuals will be instrumental in crafting your organization’s mission statement, recruiting volunteers, and fundraising for your cause. Board members should be energetic and committed to do the heavy lifting of creating a business plan, registering the nonprofit, and filing the articles of incorporation. These same people will be responsible for opening a bank account, applying for insurance, and filing with the IRS for tax-exempt status.

Like small businesses, nonprofit organizations are typically created under state law. To find resources specific to your state, visit the website for the National Council of Nonprofits, and click on the map to find your state association. In California, for example, the basic steps for starting a nonprofit include selecting a suitable name, filing articles of incorporation, appointing a board of directors, and drafting the bylaws of the organization, according to the California Association of Nonprofits.

After that, the board must officially adopt the bylaws, set the number of directors, adopt a fiscal year, and establish a bank account. For tax purposes, an officer of the organization can apply online to get an employer identification number (EIN).

Once incorporated, the next step is to apply to become a 501(c)(3), a type of nonprofit that is tax-exempt under IRS rules because of its charitable programs and initiatives. On an ongoing basis, organizations must continually stay on top of required tax filings and compliance.

While there is a lot of work involved in founding a nonprofit, the reward lies in knowing that your contributions can live on as part of your legacy through the organization’s programs and initiatives.

“I love my job, but it’s not even a comparison as to how you feel when you influence someone in a positive way like this,” says Pereira. “People deny it, but really, we all think about what our legacies will be. If you go on my Wikipedia page and read the section about when I was working for the NFL, it says I changed the officials’ uniforms from white knickers to long white pants. That’s not what I want my legacy to be. I want to know that I made a difference in people’s lives.”

Additional Resources for Launching a Nonprofit

- State-by-state resources from the National Council of Nonprofits

- National Association of State Charity Officials

- Information on choosing your board of directors

- IRS information on gaining tax-exempt status

As the retirement plan landscape has evolved, so have the investment menu options offered to participants. The Pension Protection Act of 2006 (PPA) marked a turning point in this history, creating a path to plan sponsor safe harbor regarding automatic features and qualified default investment alternatives (QDIAs). After the passage of PPA, DC plan investment menus expanded exponentially. Now the industry is seeing a trend toward condensed lineups as plan sponsors learn to craft more thoughtful menus that still allow for customization with fewer investment vehicles. While the lineup of the past centered around participant choice, the lineup of the future will likely center around participant needs.

“The key pieces of any DC plan menu are the QDIA and the core lineup,” says Peter Ruffel, a manager in CAPTRUST’s defined contribution practice. “The QDIA provides a prudent, diversified option for less engaged participants, and the core lineup lets more engaged employees cater to their own risk and time horizon needs.”

Section 404(c) of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) provides a safe harbor for fiduciaries related to participants’ investment actions. One of the requirements of 404(c) is to offer a broad range of investment options consisting of at least three diversified fund options. But the average plan typically offers much more than that.

According to the Plan Sponsor Council of America’s (PSCA) 65th Annual Survey of Proft-Sharing and 401(k) Plans, the average 401(k) plan now offers 21 investment options. “This is down from the average of 25-30 funds we were seeing a decade ago,” says Ruffel. By providing so many investment choices, sponsors were hoping to invite customization, yet many funds saw minimal uptake.

“There is no right or wrong number of investment options,” says John Hays, a manager in CAPTRUST’s defined contribution practice. “In fact, there are studies on both sides of the debate that seem to present conflicting results.” Some say too many funds can create negative outcomes. Others say that, with additional options, participants will diversify more.

In other words, although there is a trend toward condensed menus, fewer does not necessarily mean better. “There are a lot of right ways to build a DC investment menu,” says Ruffel. “What matters is that investment lineups are aligned with participant needs.”

Thoughtful Responses

Designing the optimal investment menu to meet participant needs requires being both proactive and flexible. For example, market conditions or industry trends may influence sponsors to pursue reactive menu changes, like adding multiple bond portfolios to balance stock market declines.

“Sometimes, sponsors need to react quickly, but they also need to think through the potential inertia of reactive decisions to make sure they can effectively unwind things if unwinding becomes necessary,” says Hays.

Ruffel points to the global financial crisis of 2008 and 2009. In the years following, many asset managers were touting low-volatility investment products that appealed to people’s desire for security and stability. “In the wake of chaos, low volatility sounds comforting, but as the market improved, those investors missed out on a significant amount of growth,” he says.

When evaluating reactive moves in response to market volatility, economic headwinds, or inflation, plan sponsors should consider whether each new investment will still be prudent and desirable as the market and economy evolve. Investment performance is likely to fluctuate but should meet a baseline of growth to continue earning its spot on the plan’s investment menu.

Trend following is another area where sponsors would do well to balance reactivity with a long-term view. Benchmarking investment menus against industry standards is a recommended practice, but deciding which trends to follow—and which ones may not be a good fit—will depend on each sponsor’s unique participant base. For example, a manufacturing company with 5,000 working-class employees will need to meet very different investor needs than a healthcare organization of 200 highly compensated surgeons.

“The question to ask is: ‘Will this actually benefit my participants’ accounts?’” says Hays. “The answer will depend on the organization’s goals and objectives, employee demographics, and existing participant usage data.”

It’s also important to remember that not all trends will be relevant for all organizations. “Benchmarking can’t tell you what to do,” says Ruffel. “It just helps you understand what other people are doing.” Most organizations want to be evolutionary over time—not revolutionary.”

However, some sponsors will need to break with industry trends to meet participant needs. In that case, Ruffel says, “Documenting the process you’ve used to make that decision can be just as important as the decision made.”

Another way to fine-tune investment menus is by analyzing participant behavior. “Usage data can be a good starting point when making decisions about paring things down or adding new options,” says Hays. “A low participant count or low asset total can be a strong indicator that an offering may not be meeting participant needs.” By tuning in to data, sponsors can make informed changes.

Pushing Ahead of the Pack

Proactive changes are equally important. Recently, Ruffel and Hays say they have witnessed an increase in conversations about retirement income solutions, a sustained interest in managed accounts, and detailed questions about the benefits of dynamic QDIAs, also called dual QDIAs.

Although sponsors are interested in learning more about decumulation strategies and through-retirement glidepaths for participants, Ruffel says that most plan sponsors are still early in their journeys toward providing total retirement income solutions. “Many sponsors are already offering target-date funds designed to manage assets through retirement, sometimes up to 30 years.” According to CAPTRUST data, 87 percent of 401(k) plan sponsors use target-date funds as part of their investment menus, and nearly 47 percent of total participant assets are allocated to these funds.

“Now, some sponsors are exploring evolved target-date strategies with a built-in retirement income feature or annuity option that can provide participants with a steady stream of income during retirement,” Ruffel says, but this is still a very small percentage of plans.

Although target-date funds are now an essential part of designing a DC menu, they are still a relatively recent development. “Before the PPA, it was a novel idea to use target-date funds in a retirement plan,” says Ruffel. “PSCA didn’t even start surveying plan sponsors on the use of these funds until 2012. That means there are almost certainly other aspects of menu design that we’re talking about today as proactive or future-focused but that, in 10 years, will be expected table stakes.” Managed accounts are one investment solution likely to make that list.

Ruffel and Hays anticipate an increase in managed accounts going forward. These are accounts owned by individual investors but managed by a professional investment manager that makes discretionary decisions on the investor’s behalf. Now easier than ever for participants to use and access, managed accounts allow participants to have personalized portfolios built using their individual financial situation and goals. This can be especially useful as the participant approaches retirement.

“However, these accounts may not be right for everyone,” says Hays. “For participants in their 20s and 30s, a target-date fund may be more appropriate. But for those who are 10 or 20 years from retirement, a managed account can be a helpful option to help them reach their personal retirement goals.” Hays says one important piece to consider is cost relative to the value and services received.

Plan sponsors who want to combine the benefits of target-date funds with managed accounts may choose to explore a new generation of QDIAs: those that utilize target-date funds for younger participants, but transition to managed accounts as participants approach retirement.

These dynamic or dual QDIAs can automatically adjust participants’ investment allocations based on factors beyond just age and market conditions. Instead, they look at salary, account balance, pension or other savings plans, savings rates, sponsor match, and more to provide a more tailored investment experience across the participant’s lifespan. Typically, participants will be transitioned into a managed account at a specified age when additional factors outside of risk and retirement horizon can be impactful to a tailored asset allocation.

This means even disengaged participants can receive personalized advice to optimize their retirement savings. And the more engaged participants are, the more customized the portfolios can become by adding assets outside the retirement plan and specific investment goals and objectives.

The Investment Lineup of the Future

As part of their fiduciary responsibility, plan sponsors should revisit investment menus periodically. “Otherwise, it’s easy to get stuck in the habit of scoring each underlying investment and its performance outcome only, without taking a 10,000-foot view of the lineup itself,” says Ruffel.

When evaluating which investments to add or subtract, the following questions can be helpful:

- Which investment options have the lowest engagement, either by number of participants or by total assets? Where are new contributions going?

- Do any pieces of the menu overlap with each other?

- Is the menu overly focused on one asset class or investment area?

- Are there any gaps that an additional offering could help to fill?

- What are other plan sponsors doing?

- Is a self-directed brokerage account (SDBA) option available to participants? If so, what investment options are available to them through that service?

Although the investment menus of the future will vary by sponsor, it seems increasingly likely that their core purpose will be to home in on and provide for diverse participant needs. The next decade of this evolution will likely involve a rapid development of tools, services, and products that nudge participants in the right direction in terms of how they are saving, how much they are saving, and—when they are finished saving—how they can withdraw money from the plan.

As data-analysis and money-management technologies converge, plan sponsors will be able to make better reactive and proactive decisions, informed by both internal and external data. But they’re also likely to be reminded that investment menus are only one piece of the puzzle.

“A big part of retiring well means feeling confident in your retirement savings,” says Ruffel. “Sometimes, that’s not about investments at all. It’s about tools, resources, and education. The investment menu isn’t everything. It’s just one component.”

Hays agrees. “A huge part of this has nothing to do with the plan lineup in and of itself. It has more to do with the participants’ ability to understand the lineup, use it well, and feel confident in it, so that they don’t make knee-jerk reactions every time the market declines or the economy contracts.”

Adapting to meet participant needs goes far beyond the design of retirement plan menus. It’s a shift in mindset that is likely to sweep across the broad swath of employee benefits, from financial wellness and advice programs, to health savings accounts and retirement plan design changes that can help employees pay for college and meet emergency needs.

As a lawyer advising sponsors of employee benefit plans that are subject to the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA), I am often asked to help address questions of fiduciary governance. Over the years, I have learned that identifying plan decision-makers and assigning fiduciary responsibilities—which is the heart of good fiduciary governance—requires a robust understanding of both the culture of that organization and the people who drive it.

Put simply, in order for legal best practices to actually reduce liability, increase efficiency, and encourage (or at least not stifle) innovation, the fiduciary structure put in place has to work with the organization, not against it.

In connection with fiduciary governance, I am frequently asked whether it is better for a plan sponsor to hire a third-party fiduciary to advise on plan investment or to manage those investments directly. These two types of fiduciary relationships are often described using shorthand versions of statutory citations. A 3(21) fiduciary is an investment advisor and 3(38) fiduciary is an investment manager.

Below, I briefly outline the legal differences and similarities of these two approaches and discuss some additional considerations relevant to selecting an investment fiduciary for your company’s retirement plan.

What the Numbers Mean

While it is common to label fiduciaries who provide advice as 3(21) fiduciaries and those who exercise investment discretion as 3(38) fiduciaries, both types of fiduciaries are actually described in section 3(21) of ERISA. This section defines a fiduciary as both:

- a person who has or exercises discretionary authority over the assets or administration of the plan (that is, the actual decisionmakers); and

- a person who provides investment advice for a fee with respect to the assets of the plan (that is, people who are not decision-makers but who recommend investments to decisionmakers).

One important distinction between the two types of fiduciaries is that they do different things—one advises a plan decisionmaker, and the other is the plan decisionmaker.

Another distinction arises from the way ERISA apportions legal liability. ERISA permits a named fiduciary to appoint an investment manager (as defined in section 3(38) of ERISA) to manage plan assets. This investment manager must be a discretionary fiduciary who is also registered as an investment advisor, is a bank or insurance company, and who has acknowledged in writing that it is a fiduciary with respect to the plan.

The appointment of an investment manager is advantageous for the named fiduciary because it relieves them and the plan’s trustee of fiduciary responsibilities for the investment of all assets that are under management of the investment manager, and for the manager’s acts or omissions in doing so. However, as discussed below, knowing the differences does not end the analysis.

There Is No Right Answer

While the additional liability relief that comes along with the appointment of a named fiduciary can be important, the specific needs of the plan and the services that the fiduciary is expected to provide are critical to the selection decision. For instance, appointing a 3(38) investment manager won’t be effective to relieve the appointing fiduciary of liability, unless the manager is actually given the power to manage the plan’s assets.

Any person who provides advice to a plan but does not exercise investment discretion is a fiduciary by reason of providing investment advice but is not considered that plan’s investment manager, regardless of how the parties decide to privately characterize their relationship). Status as an ERISA investment manager is functional. It is possible that certain activities such as monitoring of investment options and performance reporting may not be viewed as part of that fiduciary’s power to manage assets and thus not viewed as investment manager responsibilities.

Additionally, while fiduciary advisors and discretionary investment managers have different roles, the standards of care and loyalty that are imposed by ERISA on the two types of fiduciaries are identical—and exacting. For instance, each type of fiduciary must act in accordance with ERISA’s prudent expert standard and must avoid prohibited transactions.

And the plan sponsor that is appointing an investment manager or hiring a fiduciary advisor must monitor the fiduciary to ensure that the plan’s needs continue to be met.

In my practice, I find that like any other fiduciary governance decision, deciding how to structure a plan’s relationship with an outside fiduciary works best if informed by both legal and practical considerations. In selecting an outside fiduciary, the plan sponsor should understand the legal differences and similarities between 3(21) and 3(38) fiduciaries. But they must also consider the particular needs of the plan, its participants best interests, and the plan’s existing fiduciary governance structure.

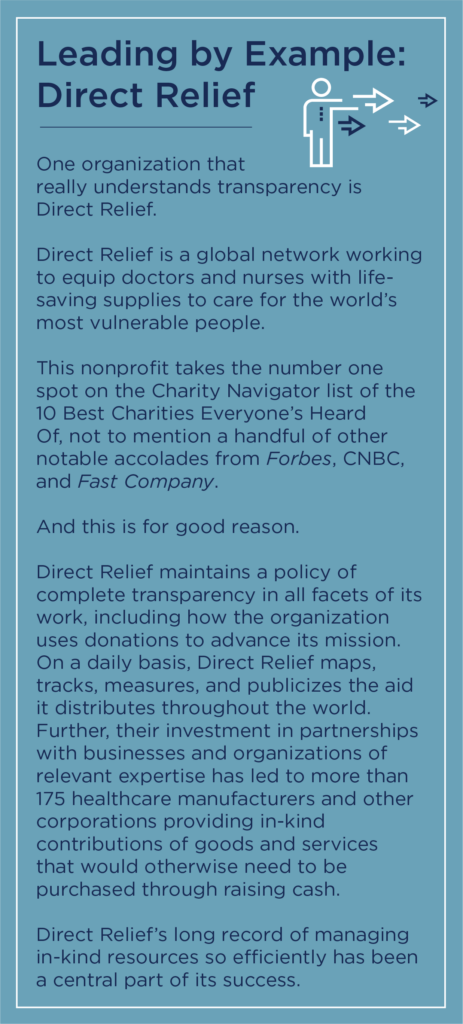

When donors give money to nonprofit organizations, they typically do not expect a tangible product or service in return. What they do expect is responsible governance. In fact, research shows that donor confidence relies directly on an organization’s governance practices. Specifically, major donations and government grants strongly correlate with formal written policies, independent audits, board independence, and accessible financial information, according to a study from The Accounting Review.

Although there is no one-size-fits-all formula for effective governance, time and experience have revealed a common set of practices that may improve board efficiency and effectiveness, thereby increasing donors’ confidence in the organization. Transparency, for instance, is especially important, with astute donors relying on sources such as Charity Navigator to assess an organization’s fiduciary management, governance practices, and administrative costs. This article explores four additional best practices for nonprofit governance that can improve fundraising outcomes by increasing donor confidence.

Committee Overlap

Consider overlapping committee members. Organizations that consider finance and investment committee perspectives when they are making governance decisions typically experience better alignment between spending, fundraising, and investing. “However, we still see plenty of organizations with investment committees that are operating separately from their finance and development committees,” says Heather Shanahan, CAPTRUST director of endowments and foundations.

“This is not a recommended practice,” says Shanahan. “When committees are siloed, it means people with insight into the organization’s investment objectives—and its outcomes—are not participating in spending decisions, and vice versa.”

“The disconnect can create significant potential for declining asset values,” says CAPTRUST Senior Director Grant Verhaeghe. To mitigate this risk, many organizations create a unified finance committee that handles budgets, investments, fundraising, and spending. Others choose to keep committees separate but create overlap through governance structures, for instance via regular finance meetings that include at least one member from each related committee.

“Ideally, spending decisions will be tied to asset performance, and multiple board members will take part in discussions about both,” says Verhaeghe. When everyone has at least a basic understanding of the organization’s assets, investment goals, current spending, and budget limitations, the board can make more informed decisions. This includes decisions related to fundraising, debt, and development. Regardless of how the organization chooses to do things, clear and frequent communication is key because it helps ensure alignment between financial objectives and results.

Continuity Through Documentation

Robust documentation is another best practice that may improve fundraising outcomes by demonstrating trustworthiness. And it’s especially important considering board member turnover.

CAPTRUST Vice President and Financial Advisor Will Chitwood says he has seen a significant uptick in board turnover since the pandemic, attributing the trend, in part, to exhaustion and burnout over that time. “We’ve witnessed board member turnover varying from regular, predictable succession to organizations that are in the process of transitioning their entire boards,” says Chitwood. “Some of that turnover was expected for board members with longer tenures. But some was certainly a surprise.”

Documentation helps new board members get up to speed faster. “The more information they can easily access about past decisions and policies, the better informed they can be and the faster they can begin focusing on the organizational initiatives that really matter,” says Chitwood. Otherwise, new members can easily get stuck trying to figure out the organization’s policies and procedures.

Shanahan suggests a few key documents every nonprofit should develop. The list includes an investment policy; a spending policy; governance policies; board and committee charters; conflict-of-interest policies; portfolio monitoring records; and, among the most important but also often overlooked, board reports and meeting minutes. She says minutes are important because “they document both the final decision and the reasoning behind it.”

Verhaeghe says documentation can also demonstrate fiduciary prudence. “Over time, the organization will inevitably make changes to its investment portfolio or spending policy. To mitigate the risk of litigation, it’s important to record the rationale behind those changes and any work that was done to back up a course of action.”

For example, a board might conduct an analysis to assess the appropriateness of a portfolio’s investment objectives. This analysis would consider time horizons, withdrawal needs, and risk tolerance—all of which should be documented to demonstrate that the organization has fulfilled its fiduciary duties.

CAPTRUST’s 2022 Endowment and Foundation Survey showed that the vast majority of nonprofit respondents had formal conflict-of-interest policies (96 percent), investment policies (95 percent), committee roles and responsibilities (90 percent), and spending policies (80 percent). However, few organizations had all four of these documents, and only 21 percent reported having a documented policy for debt. “Without a formal debt policy, among other things, it’s hard to know if an organization’s assets are going to last relative to its goals and objectives,” Verhaeghe says.

Shanahan says another common problem is that organizations are operating with outdated or incomplete governing documents. “Sustainable governance requires that all these policies are kept up to date,” she says. “Especially if board members leave unexpectedly, the only way to ensure a complete transfer of knowledge is through documentation.”

Building a Board Pipeline

Succession plans and term limits also help to ensure continuity. And they keep board members focused on the need for continued recruitment.

Nonprofit leaders can guard against the loss of institutional knowledge by intentionally crafting their governance structures with staggered term limits and by developing a board member pipeline. As Shanahan says, “Continuity starts with recruitment at the board level. And it almost never happens accidentally.”

Most boards know why succession plans are important. Yet only 12.5 percent of nonprofits report having a formal succession policy for board members, and slightly less than 30 percent currently have a succession plan in place, according to the 2021 Leading with Intent survey.

Committees are one way to manage turnover and create connections between new and veteran board members. A formal mentor-mentee relationship is another helpful tool. “Creating a matrix of current members, their term lengths, and their professional experience can help to keep board needs top of mind,” says Shanahan.

Bylaws typically limit the number of board members an organization can have, and this can create tricky issues if board members aren’t thoughtful about recruitment. “It’s easy to give a seat to an enthusiastic community member who has ample capacity to support the organization,” says Shanahan. “However, sometimes when organizations do this, they suddenly find themselves landlocked with headcount. They wake up one day to realize that, because of attrition, their investment committee is now made up of only tax professionals and attorneys. No one has investment expertise, and they can’t add new board members.” A board member matrix can help current members remember to keep a long-term view.

Education and Training

The final piece is board education and training. Verhaeghe says nonprofit boards can benefit greatly from board-level investment in fiduciary training and new board member orientation. “Sometimes, we find that board members have good intentions and a deep passion for the organization, but they lack the training, depth of knowledge, and correct understanding of their role to help their organizations succeed,” he says.

In 2022, CAPTRUST data showed that only 46 percent of nonprofits reported conducting fiduciary training for their board, finance, or investment committee members in the last three years.

Chitwood says he recommends annual fiduciary training to keep board members in the loop on new legislation, regulations, and trends. However, he admits that it can be difficult for certain boards to gather all the necessary people for additional training time, since most nonprofit board members are volunteers who have full-time day jobs. “At first, most fiduciary training focuses on the roles and responsibilities of the investment committee,” says Chitwood. “Once all board members or committee members have a solid understanding of their fiduciary duties, then training and education can be more granular.” For instance, committees might look for training on certain investment topics or on spending policy design. Regular training can also be a way to recruit future board members, make industry connections, and vet potential vendors.

Governance Considerations

In an environment of great competition for charitable donations, nonprofits with well-structured governance may be more attractive to donors. Boards that are considering making changes may want to consider the following:

- Does your organization have an overlap between the committees responsible for overseeing finance and investment?

- Does your organization tie a documented spending policy and formal investment policy together when making spending and investment policy decisions?

- Could more documentation help your board strengthen its fiduciary oversight?

- Does your organization have a succession plan for the current executive director, chief executive officer, and all key board positions?

- Do current board members have access to meeting minutes that document board decisions and their reasoning?

- Does your organization have a formal process for training new board and committee members?

Although these questions may not have easy answers, discussing them can help nonprofit board members uncover areas where they can improve their current governance processes and structures. It helps to remember that governance is a tool for ensuring organizational foresight and hindsight. With best practices in place, board members can better understand past decisions and keep focused to meet future challenges.

The Puritans required adulterers to wear a scarlet letter A as a penance for their wrongdoing. It was a visible symbol of misconduct meant to stigmatize the wearer and warn off others. For nonprofit organizations, a reputation lacking honesty, integrity, and transparency is a similar penance. It marks them as untrustworthy and limits their ability to successfully engage donors.

No longer is the word charity synonymous with virtue and integrity. Nonprofits beware. Comply, or wear a scarlet letter for lacking the ethical principles and accountability engrained in true nonprofit transparency.

Trust Issues

There is a thread that exists between transparency and profit, and that delicate strand is made of trust. Unfortunately, scandals around the mismanagement of donors’ gifts—including bloated executive salaries, board mismanagement, corruption, and massive amounts of money paid out to third-party fundraising outfits—have left today’s donors questioning the authenticity of benevolent organizations.

“When an endowment or a foundation is less than forthright, it puts a blemish on the entire nonprofit community,” says Eric Bailey, head of the endowments and foundations practice at CAPTRUST. “Sometimes it’s out-and-out fraud. Other times, it’s a lack of leadership, misalignment, or lack of mission. Nonetheless, it’s damaging.”

According to the give.org “Donor Trust Report,” 32 percent of respondents trust charities less today than they did five years ago. And 73 percent of respondents to a separate survey rated the importance of trust as nine or 10 on a 10-point scale, with only 20 percent of those respondents indicating a high level of trust in charities.

Further, about a third of Americans don’t trust charities to spend their money well, and more than 60 percent of people around the globe say they don’t have faith that nonprofits can accomplish their missions, Fast Company reports.

The public has higher expectations for organizations whose missions are to do good. “Today, people want to know more about a nonprofit’s mission, its goals, its impact, and the outcomes produced. Donors want access to detailed financial reporting, too,” says Bailey.

The fact is, donors are doing their homework before making gifts. And, according to data from The NonProfit Times, if a nonprofit organization doesn’t live up to a certain standard of transparency, it receives 47 percent less in contributions than organizations that proactively provide data to the public.

“By committing your agency to a donor bill of rights, those donors have the opportunity for transparency,” says Kristye Brackett, vice president of philanthropy at Transitions LifeCare.

Created by the Association of Fundraising Professionals, the Association for Healthcare Philanthropy, the Council for Advancement and Support of Education, and the Giving Institute: Leading Consultants to Non-Profits, the Donor Bill of Rights assures that a nonprofit organization deserves the respect and trust of the general public, and that donors and prospective donors can have confidence in the charities and causes they support.

“[At Transitions LifeCare], we are constantly having conversations about what does the donor bill of rights look like, and what are we doing to really adhere to that donor bill of rights,” says Brackett.

The More You Give, the More You Get

Don’t give donors reason to distrust your organization. Safeguard against this by making your organization’s financials easy for the public to find.

Nonprofits that are more transparent and share things publicly, like audited financial reporting, goals, strategies, capabilities, and metrics demonstrating progress and results, received 53 percent more in contributions compared with organizations that are less transparent. This is also according to The NonProfit Times.

A separate study published by the Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance, titled “Determinants and Consequences of Nonprofit Transparency,” hypothesized and found to be true that the decision to be transparent equates greater future contributions.

“When an organization provides insight into how donations are used, it adds depth and breadth to the mission that could not be gained in any other way,” says Bailey.

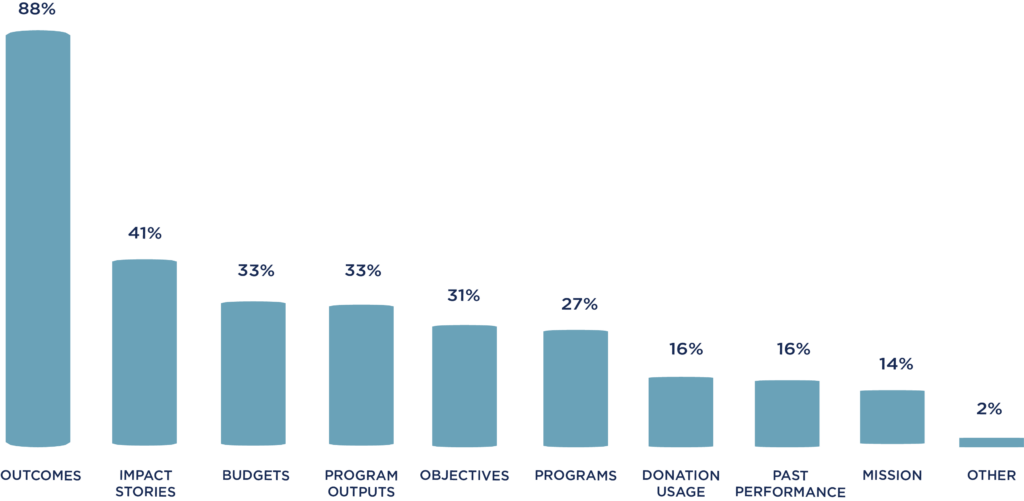

Current reporting provided by nonprofits detailing how donations are being used is expected to stay about the same or increase over the next five years. As shown in Figure One, however, donors are most interested in hearing about program outcomes (88 percent) and impact stories (41 percent).

Figure One: What Areas of Nonprofits Are Donors Interested in Learning About?

Source: “Foundation Reporting Study,” Social Solutions, 2019

Make Your Impact Known

Donors are motivated to understand who, where, and what their charitable gifts will support. Understanding how an organization demonstrates its impact is important to donors. In other words, they want to know who a nonprofit is helping, how the organization is helping them, and exactly how their gift was used.

“We know savvy people are doing their due diligence before they come to the table,” says Brackett. “Donors expect to see low administrative costs per dollar raised, with the greatest impact going back to service needs.”

As shown in Figure Two, 98 percent of donors ranked impact as the most important factor when considering making a charitable donation, followed by mission (49 percent) and legal nonprofit status (37 percent).

“In every donor conversation, we tie it back to what their dollar is impacting in the service line. We do that in not only our larger gift asks but also in our annual appeals and our thank-you notes. And we hold to the standard that the [IRS Form] 990 reflects back on that. It is spelled out in all of our materials,” says Brackett.

Figure Two: Impact Is the Most Important Consideration Among Donors

Big Brother is Watching

Fortunately for donors, there are watchdog organizations like the Better Business Bureau Wise Giving Alliance, the American Institute of Philanthropy, CharityWatch, and GuideStar, whose goal is to help inform donors by grading, monitoring, and measuring how donations flow into and out of nonprofits in relation to the goal they report. These organizations are in the business of advancing nonprofit transparency by gathering, organizing, and distributing information about U.S. nonprofits. Donors leverage these organizations to help them consider various aspects of a nonprofit’s transparency.

In a report examining if the GuideStar Seal of Transparency had an effect on fundraising, organizations with the seal were shown to be more likely to receive donations than those that had only claimed their profiles and opted to receive contributions through GuideStar. And 78 percent of the organizations that received a donation through GuideStar’s website last year were seal holders.

Depending on how much information a nonprofit provides in its GuideStar profile, the organization is identified by a specific seal that indicates its level of commitment to transparency. There are four levels; the more information provided, the higher the level Seal of Transparency awarded.

Bronze is for basic information, silver indicates full financial information has been shared, and gold means that the organization has shared all of these plus its goals and strategy. Finally, the highest seal is platinum, which indicates everything aforementioned, in addition to proven progress and results.

“Having that GuideStar Platinum Seal of Transparency is something each endowment or foundation should strive for. Donors are definitely reassured by it,” says Bailey.

Which seal an organization earns is incredibly important to potential donors. GuideStar reports that, in general, profiles with gold or platinum seals receive twice the views of other profiles. And the average donation for gold and platinum seal holders is roughly 11 percent higher than the combined average donation for non-seal holders or organizations with bronze and silver seals. Additionally, the combined average donation for all seal holders was 7 percent higher than that for non-seal holders.

Transparency Drives Traction

Charitable organizations are not powerless in shaping public perceptions about the nonprofit sector. Luckily, the dynamic nature of trust suggests the third sector can make changes that positively impact public opinion.

Transparency is not just about releasing a box of documents for public consumption. It can be a real tool for nonprofits to increase their impact through more accurate self-assessments and public engagement, leading to increased donations, more volunteers, and more positive press.

Another key piece to understand: Transparency is not a one-size-fits-all equation. What is comfortable for one organization may not be comfortable, realistic, or appropriate for another. The best transparency policy will be one guided by an organization’s mission, catered to its supporters and potential supporters, and considerate of the organization’s needs, policies, and legal issues.

“Establish great mission work that’s held accountable back to philanthropic investments. Rely on that philanthropic investment as an up-lifter of your mission and treat it very seriously,” shares Brackett. “And with that treatment and transparency, there will be more. People want to give. They are generous.”

But, with only four holes to go, Scott played disastrously, ultimately losing to Ernie Els by a single stroke in what is widely considered one of the greatest chokes in professional sports history.

The loss had a profound effect on Scott. With his confidence wounded, he began playing much more cautiously. In subsequent tournaments, he fell further and further behind, even finishing 45th at the World Golf Championships.

He hadn’t lost his skill, of course, but he stopped taking the necessary amount of risk that was required to push ahead of the pack.

The Snake-Bite Effect

Losing confidence and making overly conservative decisions in the wake of a negative experience is common and normal. Psychologists call this the snake-bite effect, and it’s deeply rooted in human evolution. Before venom antidotes were invented, a knee-jerk and overly cautious reaction was an important survival instinct.

But it may not serve us well in modern times, when unnecessarily cautious decision-making can stifle our experiences and opportunities for success. For instance, someone who gave up flying after just one turbulent flight would have limited chances to see the world.

Similarly, someone who refused to invest in technology stocks in the decade after the dot-com bubble burst would have missed out on the best-performing sector, thereby limiting their portfolio’s growth.

“The hard part about cognitive biases is that they are often unconscious and automatic,” says CAPTRUST Chief Investment Officer Mike Vogelzang. “To make prudent decisions, we have to retrain our thinking to mitigate these knee-jerk responses and be more thoughtful instead.”

Automatic Thinking

The snake-bite effect is a combination of two emotional responses: recency bias and loss aversion. Recency bias weights our decisions more heavily toward events of the recent past, while loss aversion, simply put, is the idea that people hate losing about twice as much as they like winning. Psychologist Daniel Kahneman, who coined the term, said that people feel the negative impact of a loss twice as deeply as they feel the positive impact of an equal gain. This makes people avoid losing by avoiding risk.

Put recency bias and loss aversion together and investors are primed to be overly cautious following a market downturn, such as the one experienced in 2022, or an unexpected banking event, like the one the country witnessed in March 2023.

But this type of thinking could cause investors to miss out on opportunities for growth and potentially hinder their ability to achieve long-term financial goals.

Usually, cognitive biases are buried deep in our mental mapping—a legacy from our cave-dwelling days when quick decisions and mental shortcuts could mean the difference between survival and extinction. While useful in a historic context, these biases create more problems than solutions when it comes to successful investing. Nevertheless, academic research repeatedly shows that they impact our financial decisions regardless of investment experience, age, employment history, or net worth.

Homo Economicus vs. Real People

Economic models are built on the assumption that Homo economicus—that is, the average person—will absolutely always act rationally and make decisions based on perfect information, not emotion or past experience.

Do you know anyone like that? Probably not.

In fact, Homo economicus doesn’t exist. It is merely a stylized representation of how investors should make decisions. And when we base economic models around this theoretical person, we are ignoring the behavior of real people, who almost always allow past experiences to influence future decisions.

Homo economicus is immune to the snake-bite effect—and hundreds of other behavioral biases. But the rest of us are not.

“I see the snake-bite effect most often when establishing an initial risk tolerance with a client,” says CAPTRUST Senior Director and Portfolio Manager Jim Underwood. “If a person is beginning their investment journey in the depths of a bear market, they are much more likely to enter cautiously, just when the market is most likely to reward those who take risks.”

Underwood says snake-bitten investors can be overly concerned about the potential for short-term corrections and therefore lose sight of the long-term potential wealth generation that comes from compound growth in stocks. “This bias could permanently lower the investor’s long-term wealth ceiling,” he says.

This is a critical point. While short-term investment results are somewhat random, the probability of compounding wealth in stock investments is skewed heavily in our favor if we stay invested for at least five years.

In fact, when we look at probabilities of investment success, using the S&P 500 Index as a measure, we find that trailing one-year returns have been down only a handful of times. Five-year returns have been down even less. And if we zoom out to investigate the 15-year trailing average, the S&P 500 has never been down in its history: a reminder of why time in the market is better than timing the market.

Winning the Game

Although we cannot change our past experiences, we can take actions today to overcome biases like the snake-bite effect and make better investment decisions.

One effective method is to keep a record of your major investment decisions, including rationales. By tracking the investment’s performance and your reasons for choosing that investment, you can learn to separate emotion from investing.

Remember: Every asset class goes through periods of poor performance and periods of great performance. Don’t let one bad experience limit your investment options.

Diversification is also a powerful tool. Creating a portfolio that contains assets from many different classes, industries, and geographies can help reduce the impact of negative events in any one area. While a diversified portfolio will never perform as well as the best-performing sector, more important for long-term investors is that it will likely never decline as much as the worst-performing sector.

Another antidote to the snake-bite effect is staying focused on your long-term investment goals by sticking to your personal financial plan. Financial markets move around, sometimes in unexpected and extreme ways, but a financial plan can provide comfort during those uncertain periods and help you stay focused on future goals.

Finally, you can get outside help, which is what Adam Scott did. Within a few months of his British Open meltdown, Scott began working with a sports psychologist on the mental aspect of his game. That work paid off when, less than a year later, he became the first Australian to win the tournament in a dramatic playoff.

When it comes to financial issues, we often find ourselves in the role of money coach for clients. As Vogelzang says, “It’s the advisor’s responsibility—and often, the advisor’s highest calling—to help clients manage emotional reactions and stay focused on long-term goals.” Blunting a client’s worst instincts, however they’ve been formed, and helping them avoid impulsive mistakes is one of the most important ways advisors can add value.

Unlike Homo economicus, no real person is immune from emotional biases like the snake-bite effect. As Warren Buffet said, “Once you have ordinary intelligence, what you need is the temperament to control the urges that get other people into trouble in investing.”

Using the tips above will help you avoid the negative implications of the snake-bite effect. It can also help improve the odds of winning your personal version of the game, whatever that may be.

The U.S. is one of only two industrialized nations that separate the government’s ability to spend from its ability to borrow (the other is Denmark). In 1917, Congress instituted a maximum debt limit—often referred to as the debt ceiling—to protect the government and its citizens against a blank-check mentality that could lead to unbridled spending.

While the debt ceiling worked well as a fiscal balancing tool for nearly 100 years, it has recently become a point of contention.

What is clear is that the U.S. government has experienced unsustainable debt growth, accumulating debt far greater than what it earns in any given year. And, while most people agree that the government needs to bring its budget deficit under control, building consensus behind the best approach seems full of political potholes.

The result has been a series of emotional debt-ceiling showdowns and warnings that the country may soon default on its debt. While the past few days have brought signs of optimism, a solution remains elusive. However, it is worth noting that there is an enormous gap between reaching the debt ceiling and defaulting on our debts.

When will the Treasury’s coffers run out? Answering that question is not so easy. As Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen told Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy, “It is impossible to predict with certainty the exact date when [the] Treasury will be unable to pay the government’s bills.”

But the truth is that the timing doesn’t matter. The core of the issue is that while a debt-ceiling resolution this week might delay the need to face debt problems, it does not solve the larger issue.

For a moment, let’s imagine what could happen if the debt ceiling is not raised in time. In that case, the U.S. Treasury would continue to collect tax revenue and, of course, roll over the nation’s existing debt, keeping total debt under the debt ceiling. But if access to new debt is cut off, the U.S.—like any other consumer—would be forced to reprioritize its expenses and find items to eliminate to ensure that costs do not exceed the collected revenue amounts.

We are confident that paying the interest on national debt and fulfilling Social Security obligations are at the top of the government’s priority list. These payments will be maintained, even if other, lower-priority programs are cut.

Consequently, even if the debt ceiling is not raised, the odds of default are exceedingly low. While this logic avoids a technical debt default by the federal government, it does nothing to provide job or income security for most federal employees.

But the U.S. does not need an actual default to undermine investor confidence. Following the first debt-ceiling tug-of-war in 2011, S&P Global Ratings downgraded U.S. government debt. It’s important to understand that this downgrade was not a reflection of the government’s true ability to service its debt, but rather a reflection of concerns about the government and its ability to service debt.

As former Federal Reserve Chair Alan Greenspan stated, “This is not an issue of credit rating. The United States can pay any debt it has because we can always print money to do that.” In other words, it is a matter of will.

The U.S. has the enormous privilege and responsibility of maintaining the reserve currency for most global trade. This brings an unrivaled level of stability to the U.S. economic landscape, insulating us from sudden swings in currency valuations—but exposing other countries to those same swings. As John Connolly, former U.S. Treasury Secretary under Richard Nixon, said in 1971 to his international counterparts, “The dollar is our currency and your problem.”

While losing this reserve status would require many more years of reckless federal spending behavior, the status is being targeted by our economic competitors and potential enemies. Any decline in confidence in the dollar or the government’s ability to service its debt adds fuel to this competitive fire.

With that in mind, should investors look for ways to reduce risk as the country approaches its debt-ceiling deadline?

There is no doubt that the market could experience heightened volatility as this debate intensifies and the media weighs in at an increasingly high pitch. However, this is not a short-term issue that can be solved by holding additional cash.

There are four key points to consider in deciding how to prepare.