-

Solutions

- Solutions

-

Individuals & Families

- Individuals & Families

- Individual Investors

- Executives & Business Owners

- Families with Complex Needs

- Professional Athletes

-

Retirement Plan Sponsors

- Retirement Plan Sponsors

- Corporations

- Educational Institutions

- Healthcare Organizations

- Nonprofits

- Government Entities

- Endowment & Foundation Leaders

- See All Solutions

Comprehensive wealth planning and investment advice, tailored to your unique needs and goals.Investment advisory and co-fiduciary services that help you deliver more effective total retirement solutions.CAPTRUST provides investment, fiduciary, and risk management services for nonprofit organizations. -

About Us

- About Us

- Our People

- Our Story

- Learn About CAPTRUST

-

Locations

-

Resources

- Resources

- Articles

- Podcasts

- Videos

- Webinars

- See All Resources

If you sponsor a retirement plan, you likely know there is no uniform set of fiduciary rules that apply to all plan sponsors. Instead, fiduciary responsibilities for each institution depend on the type of organization and the state in which it operates. Since state laws vary, fiduciary responsibilities can range from nonexistent to comprehensive, or fall somewhere in between. With so much variation, it makes sense that plan sponsors may feel confused or overwhelmed by their legal duties.

Those who sponsor 403(b), 401(a), or 457(b) plans have additional reason to be puzzled: some of these plans are covered by the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974, also known as ERISA, and others are not. ERISA is a federal tax and labor law, governed by the Department of Labor (DOL), that sets minimum standards for retirement plans and health plans in the private sector. The law does not cover retirement plans set up and administered by churches or government entities, such as tax-exempt healthcare organizations, local governments, or public school systems.

This means organizations that sponsor non-ERISA retirement plans are not subject to the law’s fiduciary standards. “But following ERISA best practices is generally still a good idea,” says Mike Webb, senior financial advisor at CAPTRUST. After all, Webb says, it’s not only the DOL that governs retirement plans; the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and Security and Exchange Commission (SEC) also have jurisdiction. “The IRS does not have any fiduciary rules, but the SEC has many,” says Webb. In other words, organizations that sponsor non-ERISA plans are not governed by the DOL but are still subject to SEC regulations for fiduciary behavior.

As an example, Webb points to the SEC’s regulation best interest (BI) rule, which requires that financial professionals act in the best interest of their clients—similar to ERISA’s exclusive benefit rule, which says fiduciaries must act solely in the interest of participants and their beneficiaries. To comply with varied regulations from this patchwork of governing entities, many organizations opt to adhere to ERISA standards to ensure they are following best practices.

Why Follow ERISA Standards?

For organizations that are not subject to ERISA but choose to follow its standards, risk management is typically one part of the decision. Organizations can mitigate the risk of litigation by implementing due diligence processes in accordance with a written investment policy statement (IPS).

But another, perhaps bigger part of that decision is that ERISA best practices are designed to help create optimal outcomes for employees, says CAPTRUST Financial Advisor Michael Sanders. Nonprofit organizations, like many private sector organizations, feel a moral and ethical responsibility to be good stewards. They want to do the right thing for plan participants, and ERISA standards help them define what the right things are.

“ERISA standards are just good, healthy practices,” says Sanders. “Think about things like benchmarking your plan and not leaving investments in the plan that are no longer relevant or are underperforming. If these things are done right—if these best practices are followed—they’re going to lead to better results for your employees, whether you’re in the public sector or the private sector.”

ERISA standards help plan sponsors focus on their unique employee populations and work backwards to understand what participants will need to retire successfully. “First responders are a good example,” says Sanders. “People who work in police forces or in fire departments tend to retire about 10 years earlier than the average American because those are such physically demanding jobs. If you sponsor a retirement plan for first responders, you need to be set up to provide the best outcomes for this unique group, knowing they may need to retire long before the usual retirement age.”

Do ERISA standards help organizations protect themselves from legal risk? “They can,” says Sanders, “but that isn’t really the point. The point is to create the best possible outcomes for the people in your plan. Whether or not you are legally defined as a fiduciary, you are still responsible for and accountable to participants.”

Best Practices to Consider

Webb and Sanders offer six best practices for non-ERISA retirement plan sponsors to consider. These practices can help optimize outcomes for plan participants while also improving operational efficiency.

- Enroll in regular fiduciary training. “Look for ongoing training that is similar to ERISA training but also accounts for your state’s unique rules and regulations,” says Webb.

- Have written policies in place. This includes an IPS, a summary plan document, and an investment committee charter. A written charter gives your investment committee the power to make decisions about plan investments, service providers, and more.

- Implement regular investment committee meetings. Typically, this means once per quarter. Take minutes to document all decisions and the reasoning behind them.

- Commit to annual fee benchmarking. “You want to make sure that people are paying the right amount of money for each plan service,” says Sanders. “Reviewing fees on an annual basis will help you be sure that things aren’t drifting away from what’s reasonable and fair.”

- Do your investment due diligence. “Plan committees should be monitoring investments against certain benchmarks,” says Webb. For instance, you may choose to measure large-cap stock fund performance against the S&P 500 Index and core bond fund performance against the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index, two widely followed and representative indexes.

- Communicate and educate. “Participants should be notified any time you make changes to the plan, whether that means swapping out an investment or changing your processes to account for evolving rules and regulations,” says Sanders. “Remember that you are a trustee of participants’ assets, so it’s always a good idea to make sure they know what’s going on.”

Consolidation of recordkeepers is also a good idea, although some state laws require nonprofits to have more than one recordkeeper in place. “One recordkeeper is the best practice,” says Sanders. “Having two will often lead to additional work and can complicate plan administration and communication. And to the best of my knowledge, there is no data that says having more than one recordkeeper creates better results.” If your financial advisor is performing regular fee benchmarking, one recordkeeper is all you need.

However, Webb cautions, you’ll want to be aware of any applicable state laws that mandate additional service providers. For instance, “California and a few other states have any willing provider laws that say 403(b) plan sponsors have to enter into contracts with all qualified providers that are willing to accept their plan’s terms and rates.”

Depending on the state in which your institution operates, you may be required to adopt state laws that seem to contradict fiduciary best practices, including those listed here. Webb’s advice: “Wherever state law allows, follow the ERISA standard.”

Partnering with a financial advisor who has experience with nonprofit retirement plans can also be a huge help. “If you don’t have anyone in your organization whose job is to manage employee benefits, operating a retirement plan becomes even harder,” says Sanders. “You don’t necessarily need an advisor who specializes in non-ERISA plans, but you will want someone who understands the public market and how it differs from the private sector.”

Plan sponsors can hire service providers as prudent experts to handle fiduciary functions, but they cannot outsource responsibility completely. “The fiduciary retains the responsibility of monitoring the service provider itself,” says Webb. That’s why it’s critical for plan sponsors to stay familiar with evolving federal and state laws where they operate.

To be sure you’re fulfilling your fiduciary responsibilities, stay focused on employee needs and tap into expert help when you need it. Even if your organization’s retirement plan is not subject to ERISA regulations, following ERISA best practices may be prudent.

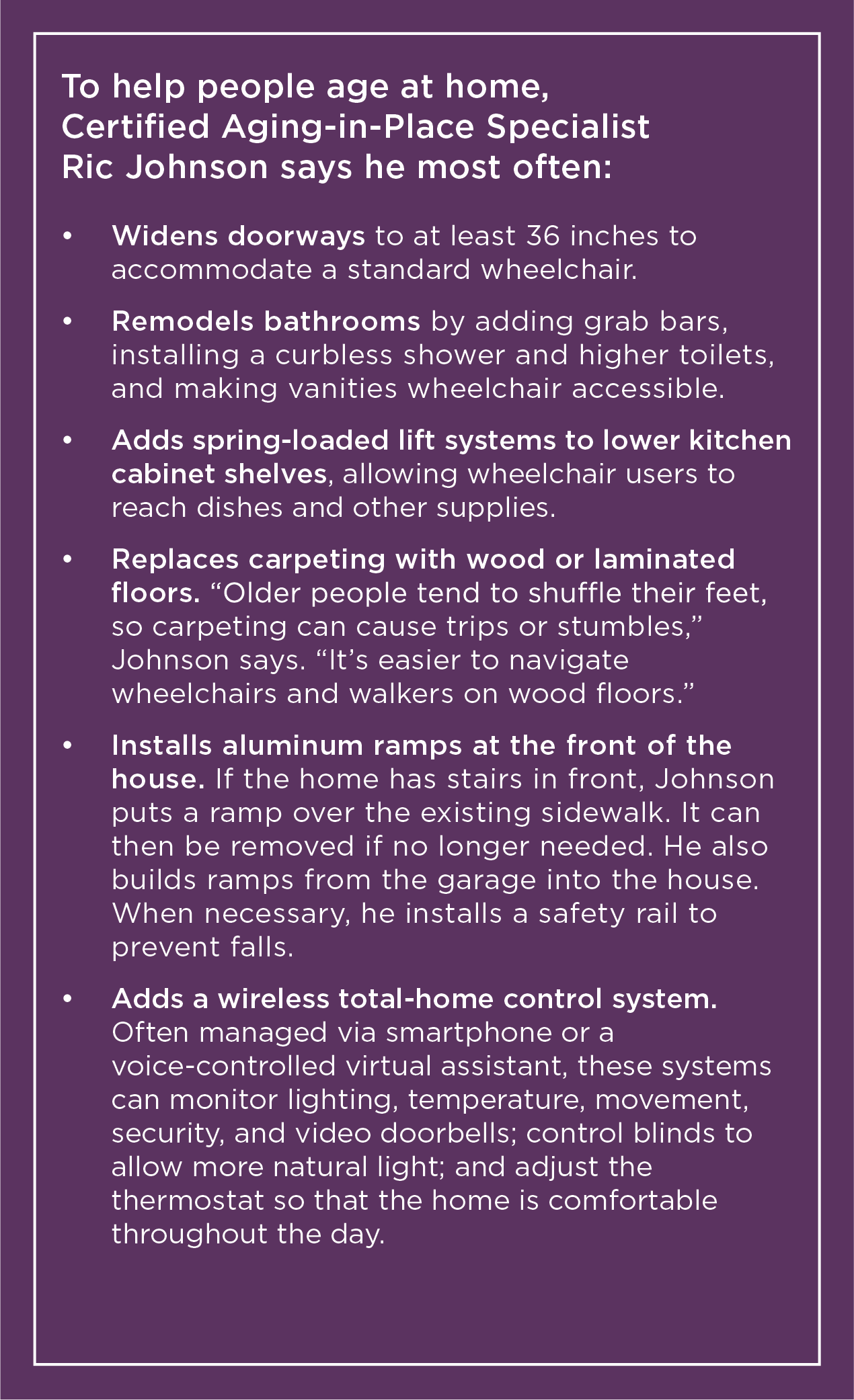

Next, they plan to expand the width of the inside doorways and renovate the bathrooms to install curbless showers in case they ever need a walker or wheelchair.

Like many Americans, the Johnsons plan to age in place. Almost 90 percent of people 65 and over want to age in their current homes or communities, and 77 percent of those 50 and older want to remain in their current homes as they age, according to AARP surveys.

“Most people want to stay where they are comfortable and familiar,” says Ric Johnson. “They want to remain in the neighborhood where they have friends and know the stores and services. Many times, there are a lot of memories in their house.”

Johnson has given this subject a lot of thought. He’s CEO and president of CAPS Builder, which specializes in making renovations and building custom homes that allow for long-term living. He’s also a trustee for the National Association of Home Builders’ 55+ Housing Industry Council.

“If your home is comfortable and doesn’t have a lot of major underlying problems, then it’s probably worth remodeling,” says Johnson, who is a Certified Aging-in- Place Specialist (CAPS), a designation awarded to those who have completed the CAPS training program developed by the building association and AARP.

“It boils down to whether it’s a home where you can live mostly on one level,” he says. “Then the other levels can be used for storage or as a place where the kids and grandkids can stay when they come to visit.”

Weigh the Options

At some point, most people must decide if they want to remodel their current home and stay there, build a new home, move to a more accessible place, relocate to a retirement facility, or transition to a continuing-care retirement community (also called a life plan community) that offers independent living residences and access to graduated levels of care, says Ryan Jantzen, a CAPTRUST financial advisor in Folsom, California.

“This is something we’re all going to have to think about—whether for ourselves or our parents,” Jantzen says. He advises clients to start considering options when they’re in their 50s so they can be “proactive instead of reactive if there’s an emergency or their life circumstances change.”

Jantzen’s own parents were able to remain in their home, which was one level and needed only a few modifications, such as grab bars in the bathrooms. However, the couple’s mountain retreat had stairs, so they added a chairlift to reach the second-floor bedroom.

His mother, who had Parkinson’s disease, lived at home until she passed away eight years ago. His father, 80, is still on his own. “He is happy to be independent,” Jantzen says.

Evaluate and Prepare

If you or your parents want to age in place, have the home evaluated and modified for safety and accessibility, says occupational therapist Lynda Shrager, a CAPS in Slingerlands, New York, and author of Age in Place: A Guide to Modifying, Organizing, and Decluttering Mom and Dad’s Home.

Shrager often gets calls from adult children who want her to assess their parents’ living situation. Most of the time, she goes to the residence, but she can also do an evaluation virtually.

She starts by watching the homeowner go in and out of the front and back doors. Then, she observes them in every room as they get on and off the furniture and toilet and in and out of the shower. “I watch them reach for their favorite cup and saucer in the cabinet,” she says. “By observing them navigate their homes, I can see where they are having trouble and what’s causing the trouble.”

After the assessment, she recommends modifications. “I have never done an evaluation that didn’t require adding grab bars,” Shrager says. They’re often added outside and inside the shower, as well as near the toilet and other areas of the house. Some products double as towel racks or toilet paper dispensers, she says.

Johnson says most of his clients remodel a section of the first floor to accommodate their needs or those of an aging parent. Some choose to add an in-law or caregiver suite to the main levels of their homes. Renovations are usually done in the kitchen, bath, and hallways. Plumbing and lighting may also need updates.

The goal is to make changes to the home without making it look like an institution or hospital, Johnson says. For instance, if a client needs handrails in the hallways, he adds a wainscotting rail that matches the decor of the house. “It looks elegant, not utilitarian.”

Johnson encourages people to try to live on one level, but if necessary, he installs chairlifts. “We seldom add an elevator to an existing home,” he says, because an elevator needs an engineering study and drawing and requires quite a bit more research and planning.

Every project is different, but typically, Johnson’s clients spend $80,000 to $200,000 to remodel their homes. Most people recoup their investment when they sell the home because it now has a universal design, which makes the house accessible to anyone at any age, he says.

Build a New Home

Rather than remodeling, some people decide that starting fresh is the best solution. Max and Kelly Fregoso, 56, of El Dorado Hills, California, sold their 6,500-square-foot home last spring when the market was hot and are now custom-building a home where they can age in place, as well as care for Kelly’s mother, who is 79.

Their new 4,200-square-foot, one-story home will have wide hallways, wide doorways, no step-ups, and bathrooms that are wheelchair accessible. It will also have a bedroom with an ensuite bathroom for Kelly’s mother, who has poor eyesight. The bathroom has grab bars and a bench inside the shower. “Her bedroom is near ours, so we can hear her and keep an eye on her,” Kelly says.

They’re excited to remain in the community where they raised their two girls—staying close to their adult children as well as to extended family and friends. “This is our forever home,” Max says.

Analyze the Costs

Whether you’re inclined to remodel or build something new, when weighing the pros and cons of aging at home, you should factor in the costs of in-home care. Many older adults can stay in their homes with intermittent help from a caregiver, Shrager says. For instance, they may have someone come in for two hours in the morning and two hours in the evening to help with bathing, dressing, taking medications, and preparing meals.

Costs will vary depending on where you live and the level of care you need, but the median cost of home care in the U.S. is about $26 an hour. In West Virginia or Louisiana, the average price is $19 an hour. In Minnesota and Washington— the most expensive states for home care—prices hover closer to $35 an hour.

The same variation exists in prices for residential facilities, but near Albany, New York, a high-end nursing home is about $130,000 a year, and assisted living facilities cost around $75,000 or more, Shrager says.

Calculate the Bottom Line

In addition to traditional financial planning services, Oliver Norman, a CAPTRUST financial advisor in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, helps some clients compare projected costs associated with long-term care options with the costs of renovating their current home.

“We model and plan around lots of different situations,” he says. “We give a lot of thought to where clients are going to live for the next five to 10 years.”

In the end, it’s a personal decision, says Fred Sloan, a CAPTRUST financial advisor in Lake Success, New York. “Remodeling to stay in your home is a gift to yourself,” he says. “You have the right to spend your money the way you want.”

Sloan, 64, and his wife chose to downsize from their house on Long Island to a condo in the same area. They also bought a one-story, age-accessible home in Florida. They made the changes to simplify their lives and make things easier as they grow older.

“When we can no longer climb the stairs in our condo in New York, we can hole up in Florida,” he says.

Johnson also downsized. In 2017, he and his wife moved from their two-story 1890s farmhouse, where the couple had raised their three children, to their current one-story 1957 home in a nearby town. He’d had hip replacement surgery, which made them rethink living in a home with stairs.

“I have a better understanding of what clients go through due to the medical issues I have had,” he says. “When we’re finished remodeling this home, my wife and I will have a comfortable, safe, and accessible home that we can use well into the future.”

Jim Morgan, Fall 2015

Serial CEO Jim Morgan, now 75, appeared on our cover in fall 2015, near the start of his second try at retirement. The first try didn’t go so well—a common theme among turnaround leaders like him, who often find themselves drawn back into the workforce.

After a long and impactful career in financial services, Morgan came out of retirement to work as CEO and board chair of Krispy Kreme. By all accounts, it was the right decision for both Morgan and the doughnut brand, but this second time, he wanted to make sure his retirement decision would stick.

To reset his habits after retiring from Krispy Kreme, Morgan instituted a self-imposed gap year, saying no to all recurring commitments that didn’t align with his top three priorities: faith, family, and friends. He says this gap year gave him time and permission to be more selective about what he said yes to.

“I get to pick and choose what I’m busy with and then go out there and try to make a difference,” says Morgan. “That’s why the time I took off was so helpful, because it made sure I didn’t rush into anything.”

Since then, he has stayed on a few corporate boards but spends most of his time volunteering at church and checking in with people he loves and admires. “I lead a young couples’ class at church, which is one of the great joys of my life now,” says Morgan. “And I spend a little of every day reaching out to some of the people who made a difference in my life.”

Sometimes, that means good friends or colleagues who shifted his trajectory. Other times, it might mean someone he met just a few times but who made a big impact. “It could be a schoolteacher or the widow of a friend or somebody I let go of at work but not in the right way,” says Morgan. “Contacting those people brings me all the joy in the world. It’s something I didn’t take the time to do often enough when I was working.”

Morgan and his wife, Peggy, also made the big decision to move away from Charlotte, North Carolina, landing on the South Carolina coast. “That was not an easy decision, to leave our church and our friends, but we felt called to a quieter place,” he says. Has it worked out as he expected? Yes and no.

“I came down here with the intention of being somewhat antisocial,” he says. “But I can’t help it! I meet people here, and the next thing I know, I’ve discovered that there are wonderful friends all around me. You meet some very special people just walking their dogs on the beach.”

Morgan says he’s still amazed at how busy retirement can be. “I don’t mean busy in a bad sense, but I’m surprised at how many opportunities come up to give you wonderful things to do.”

Retirement has helped him realign his passions with his calendar. “Time is too precious not to be passionate about what you’re doing,” he says. “But that doesn’t have to mean everything you do has to be something big.” For Morgan, walking on the beach at sunrise, spending a few hours volunteering at church, having dinner with his family, and taking time to write a thank-you card are all passion projects.

Nancy Volpe-Beringer, Fall 2020

“If I were young again, what would I want to learn?” That’s the question that launched Nancy Volpe-Beringer into a new career at almost 60, turning from education to the unknown world of fashion design. At face value, her story sounds like reinvention. But it’s more of an expansion—a way to grow outside the boundaries of her tried-and- true, familiar self.

“It’s not a second act. It’s a continuing act,” she says. “I really believe there’s a reason for everything. Everything I’ve done leads me to the next step.”

At 64, Volpe-Beringer made history on Bravo’s Project Runway as the oldest designer to compete in the reality TV series. Since then, she has founded an eponymous high-fashion brand (NVB), launched the world’s first luxury resale platform for people with disabilities, and earned high praise for her work in sustainable and adaptive fashion.

Her newest project—The Vault by Volpe-Beringer— is a pandemic brainchild. After a 2020 fire in the basement of her building rendered her homeless and displaced, Volpe-Beringer and her team found temporary studio space outside Philadelphia.

They moved her belongings, including her personal consignment collection, to the new space in trash bags. “I had so many clothes stored in closets,” she says. “It was like in a cartoon. You’d open a closet, and everything would fall out.”

Seeing her collection in a heap spawned an important aha moment. “I wanted to be an adaptive designer because I know what it feels like to be excluded, and people with disabilities are typically shut out of high fashion,” says Volpe-Beringer.

“One morning, we’re doing inventory, and I just thought, Why am I waiting? So I did the research, and nowhere in the world is there an online luxury consignment store that adapts for the disabled,” she says. “I thought, I’ll just start by selling my own clothes!” And the Vault was born.

Vault shoppers choose from couture items and then name the custom adaptations they want and need—a novel approach in an already creative industry.

So far, the platform has gained major accolades, including a 2022 Fashion Group International award for Rising Star New Retail Concept. And throughout New York Fashion Week, Volpe-Beringer, now 68, was featured on a Times Square billboard as one of 10 women entrepreneurs reshaping sustainable fashion, an experience she describes as humbling and surreal.

But those accolades haven’t translated to sales, which is frustrating for Volpe-Beringer. “Fortunately, because of my age and having some investments and my pension and a place to live, I can keep this going,” she says. “But I would like it to become financially sustainable.”

When asked what she’s planning for the next five years, Volpe-Beringer gives an unconventional answer: “I hope I get knocked off! I mean, I hope somebody copies my idea,” she says. “I want to be a voice in fashion for those who are not heard. But I don’t want to be the only voice. It’s time for more people to jump on board.”

Jamal Joseph, Winter 2019

In his 70 years, Jamal Joseph has earned more than a dozen remarkable titles, including poet, playwright, producer, teacher, activist, advocate, convict, father, husband, Black Panther, and Academy Award nominee. Now approaching his 25th year at Columbia University’s School of the Arts, he’s also the co-founder of IMPACT Repertory Theatre (IMPACT), a New York City community group of youth activists who use creative arts and leadership training to improve the world.

Since his Second Act story appeared in VESTED, Joseph says IMPACT has shifted how it thinks about and implements its body of work. “The pandemic meant we had to start pushing out more often into the community,” he says. “There were still in-person classes, but a lot of the work shifted to outreach in schools and community centers.” In addition to its usual leadership training, IMPACT teaches students how to improve their positive thinking skills.

Joseph believes in the power of positive thinking. “When times become uncertain or frightening, it’s even more necessary to make the choice to think positive, but that’s hard to do alone,” he says. “It’s hard enough when you have a group to turn to or a place like IMPACT where you can go two or three times a week. But when you’re in isolation with the uncertainty of the pandemic, you really need your positive posse around you to reinforce that you can make a choice to be happy.”

Joseph doesn’t just teach these skills; he practices them too, reminding himself that the law of conservation of energy is a scientific fact. Through it, we can reenergize ourselves by sharing energy with others.

“Energy can’t be destroyed. It can only be transformed,” says Joseph. “If we remember that, then even when negative energy comes our way, we have the ability—through positive thinking, through love, and through activism—to transform it. I tell the students: ‘When times get tough, keep a positive thought, because a positive thought cannot be denied.’”

What else is he working on outside of IMPACT? The list includes a TV show based on his autobiography, Panther Baby; a docuseries called Dear Mama about Afeni Shakur and her son, the rapper Tupac, who was Joseph’s godson; a documentary called Black Law, which looks at how the legal system has affected Black people, from enslavement to the installment of Supreme Court Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson; and another documentary that tells the story of the Greater Harlem Chamber of Commerce, in celebration of its 125th year.

In other words, he’s keeping busy but also making time for renewal. When he starts to feel depleted, Joseph says, he reminds himself to prioritize rest and dreams.

“Part of it is just getting extra sleep or taking that little bit of a power nap. When you close your eyes, take time to dream, by which I mean conscious dreaming,” he says. “Take time to remember all the great things that have happened. Remember all the possibilities. Remember that you’re not in it alone.”

Cindy Eckert, Fall 2018

Cindy Eckert is unapologetically and relentlessly for women. After fighting the Food and Drug Administration to approve what’s often called the female version of Viagra (Addyi), then selling her business for $1 billion and buying it back for next to nothing, Eckert says she “had a front-row lesson in what it means for women to advocate for themselves and each other.” Now she’s on a mission to make more women billionaires.

Through The Pink Ceiling, her venture capital fund, and the Pinkubator, her start-up incubator, Eckert leverages her expertise, money, and network to improve outcomes for other women founders. Two projects she has invested in recently include Bobbie, the only U.S.-made, European-style organic infant formula, and uMethod, the world’s first personalized prevention plan for Alzheimer’s and cognitive decline.

“What I want for all women, whether entrepreneurs or not, is prosperity on their own terms,” says Eckert. “The pandemic gave so many women this sense of if not now, when? My greatest joy in running the Pinkubator is that I get to see how many women left the workforce and started companies for themselves. Now, they have ownership of their own financial and personal freedom,” she says.

What’s changed for Eckert since her cover story in 2018 is that she has become more aware of—and intentional about—how she interacts with people. She’s become a better communicator, both personally and professionally.

“We went from having conversations about the business fundamentals to conversations about the emotional toll of building a business,” says Eckert. “I watched founders who were trying to keep teams together, keep culture intact, and raise money, and it forced me to have conversations I wouldn’t have had before about how founders are taking care of themselves and whom they can lean on in their networks.”

Eckert also noticed a trend among the most successful companies—something she calls customer and employee distancing. “So many companies blamed resource constraints and used them as an excuse to push people away,” she says. “But the winners on a go-forward basis will be the folks and businesses who recognize that connection is critical, whether that means connecting with your employees, your customers, your neighbors, or your friends.

“You can only win loyalty with attention, and ultimately, attention translates to sales and employee retention,” says Eckert.

How does she encourage people who want to start their own second acts? “I tell them, ‘The best bet you’ll ever make is on yourself,’” she says. “We often hesitate because we’re worried we will jeopardize all the things we’ve already earned. But that is your backup plan! Your backup plan is what you’re doing today! The greatest risk is not taking the risk and seeing what the upside potential might be.”

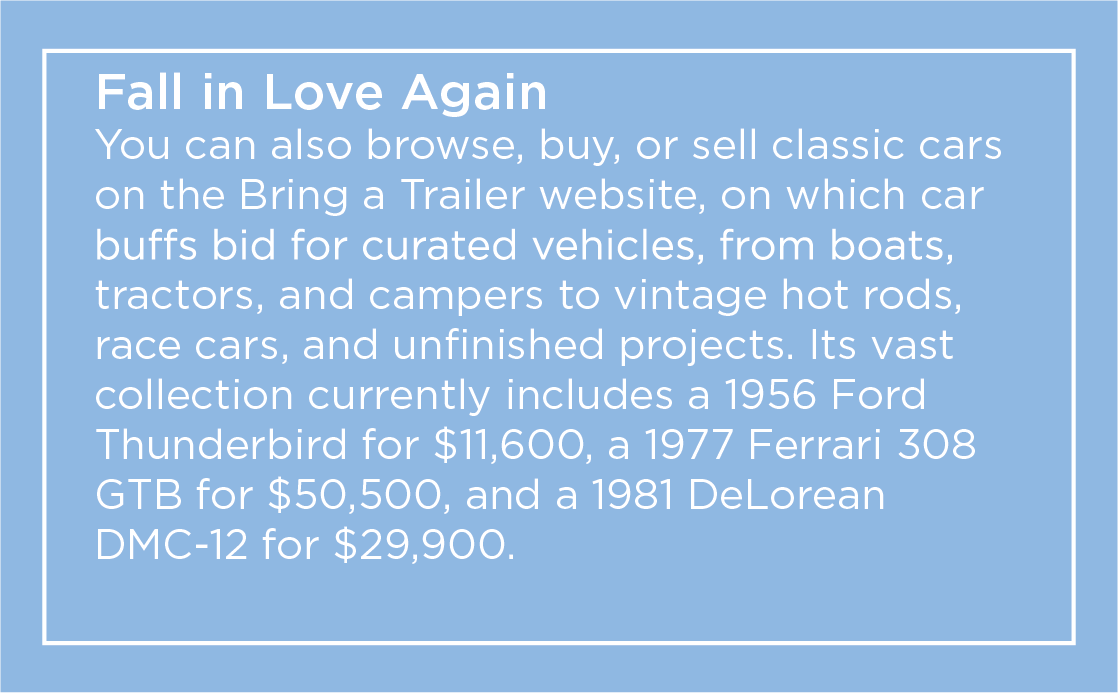

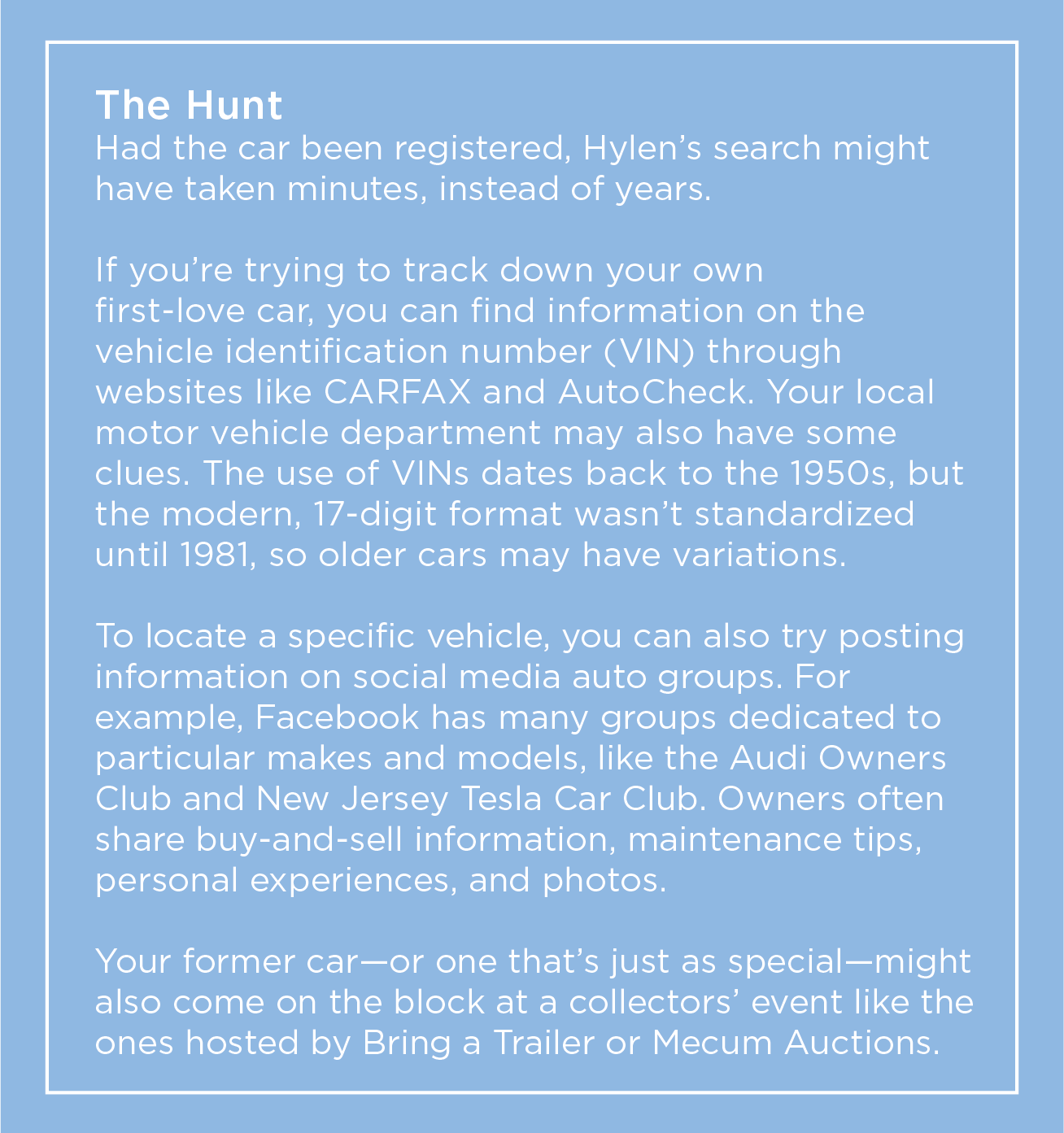

At work one day, a co-worker told Hylen that he knew just the place to find a vintage car. He’d seen a house in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountain range with about 30 junk cars scattered throughout the property— including a 1969 Firebird. “This old guy has one parked under a tree that’s been there for 10 years,” Hylen recalls the co-worker saying. So he drove out to take a look.

First Sight

White with a blue vinyl top, the Firebird was in terrible condition, but that made no difference. Hylen loved it anyway. He knocked on the owner’s door and offered all his money for it. His offer was accepted.

With his dad’s help, Hylen hauled the Firebird home on a trailer and devoted hours of work to get it running, rebuilding the car’s motor and transmission. He drove it everywhere through his junior and senior years of high school. “Once, I hit a tree in our driveway and had to put a different fender on it,” he says. It was a black fender that someone had lying around, so the car developed a multicolored look.

After the accident, Hylen wanted badly to do a proper restoration of the Firebird, but he figured he’d never have the $30,000 or $40,000 it would cost to do things right. Plus, after graduation, he was leaving town to join the Marines. So he bid a sad goodbye and sold his beloved car.

Love and Loss

Cars, especially vintage cars, have their unique personalities. It’s hard not to smile and sigh when remembering the loyal, if flawed, rust bucket that shuttled a fresh, enthusiastic, and younger you to dates, dances, jobs, and adventures. Even when it broke down on occasion or you got into that first accident, those difficult moments became memories of growing up.

A first-love car isn’t just a machine. It’s a trusty sidekick, a partner in crime, a taste of freedom, and a gentle reminder of responsibility, usually at a time when life feels like an open road ahead of you.

For many people, a first-love car isn’t the first car they ever drove or owned but one they spent time dreaming about, saving for, or fixing up. Because they feel a close connection, losing that car can feel like losing a friend or family member, like it did for Hylen.

A Reunion

Hylen kept the Firebird in the back of his mind as the years went by. He served in the military; returned home to the Sacramento, California, area; got married; and became a sergeant in the Sutter County Sheriff ’s Office. Six years ago, he dug up the number of the guy he’d sold the Firebird to and called, asking hopefully, “Do you still have it?”

He didn’t, but referred Hylen to someone else, who gave him yet another contact. Hylen doggedly left messages and followed up on leads. He searched online for clues to its whereabouts using the Firebird’s vehicle identification number, but it didn’t appear. Hylen figured it was likely off the road, parked somewhere in a yard or garage.

Nearly two years later, he finally reached someone who had information. “I heard that it got torn apart,” he says. “I found it in a field. It was open, with no windshield— rotting away. It was in worse condition than the first time I bought it.”

Again, Hylen knocked on a door. When the owner learned of the car’s special meaning, he initially asked for $5,000, despite the car’s dilapidated state. Hylen managed to talk him down. “I’ve bought it twice, for a total of $1,900,” he laughs.

The Second Act

Since reuniting with his first-love Firebird, Hylen has taken great pleasure in a painstaking part-by-part restoration. “This time, I’m writing the checks to get the restoration done perfectly,” Hylen says. “That was the money I couldn’t spend to fix it up back when I was a teenager.”

“I’m not restoring it to factory condition,” he says. “I’m modernizing it to a pro-touring car, with updated brakes, tires, engine, suspension, heat, and air conditioning. Each body panel has been replaced. It has a modern motor and transmission: an all-aluminum LS3 from a Corvette.” So far, he’s spent well over $10,000 on the interior and ordered specially cut rims for $8,000.

The mismatched blue-white-black color scheme is gone, replaced by a custom gunmetal gray paint job he has wanted since his high school days. He drove from dealership to dealership—Audi, Porsche, Land Rover—to compare different finishes and get just the right shade. “I love that it’s tough looking but still sleek,” he says. “It’s actually a Porsche color.”

The restoration and modernization, or restomod, is on track to be completed in 2023. “It’s been a 25-year journey with this car,” says Hylen. “I’m 41, and I’m finally getting the car I wanted when I was 14, except it’s so much better. This car is going to drive like a new Corvette or Camaro.” He’s spent $100,000 altogether and plans to insure it for $140,000.

During the nearly five-year restoration, Hylen has connected with an active community of classic-car buffs in his area. Friends frequently bring their own rehabbed or restored vehicles to local auto shows, but Hylen hasn’t gone to any yet. He is biding his time for his car to be finished to debut it at a huge car show. “This summer, I’m going to drive it up to Reno for Hot August Nights,” he says. “I’m so excited.”

Frank blames herself, she says, for not knowing enough about her finances or divorce law and then rushing to complete the painful and costly process.

“I gave him free rein,” says Frank. “He did nothing wrong.” Frank lives in Hollywood, Florida, and has written two books: Divorced After 56 Years: Why Am I So Happy? and Life Has No Expiration Date: Misadventures of a Single Senior.

Divorce, at any age, comes with emotional costs. But, as Frank learned the hard way, a so-called gray divorce—a marital breakup after age 50—can also cost a lot of money, as years or decades of interrelated finances and acquired assets typically require extensive work to sort out.

“Divorce is definitely a financial hit for almost everyone,” and older couples face some extra challenges, says Randi Albert, an attorney who is a divorce mediator in Scotch Plains, New Jersey. The costs can be especially steep, experts say, for people who go into the process with too little information or planning.

Regardless of marital status, “it’s important to be aware of all your financial ins and outs, whether you are the money person in a relationship or not,” says Karl Eggerss, a CAPTRUST financial advisor in Boerne, Texas.

Even those who are happily married need to understand their personal finances to make good financial decisions. Yet Eggerss says he often sees couples rely on one person for financial management while the other partner remains disengaged.

CAPTRUST Financial Advisor Catherine Seeber, from Lewes, Delaware, agrees: “It’s common for one person to make all the financial decisions. I strongly encourage anyone who’s going through or considering divorce to talk to a financial advisor and understand all the things they need to gather to educate themselves. Otherwise, it can turn into a very emotional and reactive situation. Remember, a lot of irrevocable decisions are going to be made during this time.”

The Gray Divorce Trend

Gray divorce is much more common than it once was. Even as the overall U.S. divorce rate fell, the rate of divorce at age 50 and over doubled between 1990 and 2010, according to researchers at Bowling Green State University (BGSU). Since 2010, divorce rates over age 65 have continued to rise. Someone over age 65 was three times more likely to get a divorce in 2019 than in 1990.

More than one-third of all U.S. divorces now occur among people over age 50, researchers say. What’s causing all this later-life divorce?

Conventional wisdom says such divorces happen when a suddenly empty nest, a retirement, or a health crisis puts a rocky marriage to a test it simply can’t pass. But a recent study found no link between those transitions and post-50 divorce, says I-Fen Lin, a professor of sociology at BGSU.

Instead, Lin says, the trend is driven by generational shifts. Because baby boomers—now ages 58 to 76—entered adulthood just as divorce gained wide acceptance, they’ve remained more likely to divorce than generations before or after them. This is a generation that believes “it’s better to be alone than to be in an unhappy marriage,” she says. There’s also a snowball effect because remarriages are two and a half times more likely to end in divorce than first marriages. So remarried baby boomers often end up divorcing again. Today’s aging couples also live longer, giving them more time to divorce.

Another factor may be financial. According to Lin’s research, the odds of gray divorce are 38 percent lower for those with more than $250,000 in assets than those with $50,000 or less.

Lin and her colleague, Susan Brown, looked at the financial fallout of gray divorce and found a sobering picture, especially for women. Divorced women over age 50 see an average 45 percent drop in their standards of living after divorce, and men see a 21 percent drop. Men and women each lose about half of their wealth, including real estate, investments, savings, and other property, most likely as a direct result of divorce settlements.

If they remarry within a decade, most women regain their living standards and some of their wealth. But three-quarters stay single, Lin says. Remarriage does not help men regain their living standards or wealth. And because of their ages, gray divorcees have limited time to rebuild wealth in the future.

Do Your Homework

Fortunately, experts say, there are things you can do to soften such financial blows.

Eggerss says his first piece of advice is to take it slow unless there are strong reasons for haste. He likens the period around a marital breakup to the period around a death, when it’s wise to delay major life changes. “When people are under stress, they’re going to make really bad financial decisions,” he says.

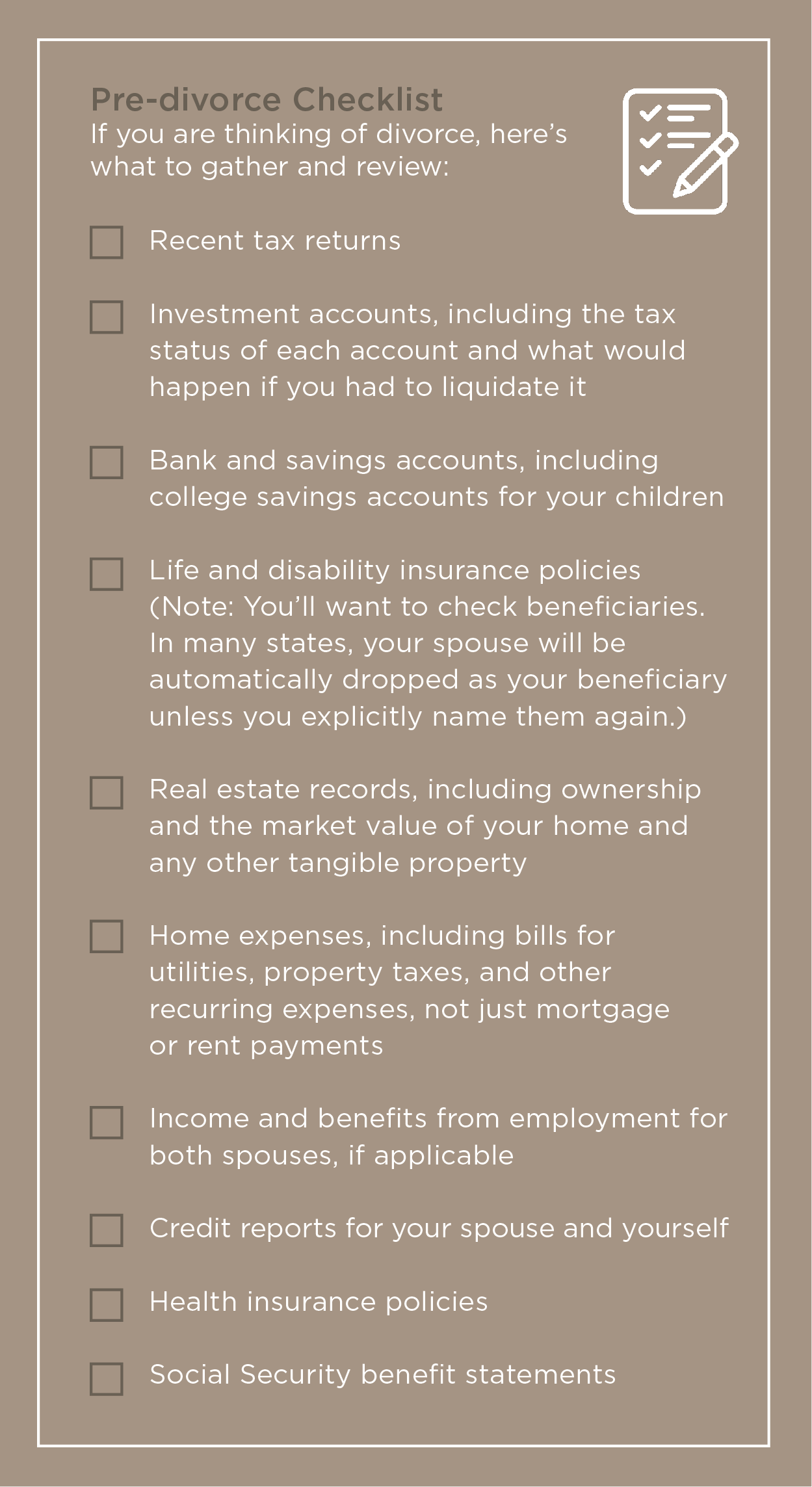

That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t think about money. On the contrary, it’s crucial to do your homework on what assets, debts, income, and expenses you and your spouse have—and how a divorce might affect your bottom line, Eggerss and other experts say.

“I think a lot of people are putting finances on the back burner,” Eggerss says, “and then make this decision before they have really thought through whether they can afford to do it.”

If you haven’t paid close attention to family finances in the past, it’s especially crucial to get up to speed. Start by gathering account passwords, Seeber says: “Ensure you have online access to anything and everything financial.” You will want to see everything from your spouse’s credit report to their Social Security statements.

Keeping communication open and civil will make information exchanges easier, Eggerss says. Whatever you do, he says, don’t try dirty financial tricks, like funneling money into new accounts you hope to hide from your spouse. Such maneuvers are likely to be uncovered, he says: “You are not going to get away with it.”

Negotiate a Settlement

If you decide to move forward with a divorce, you and your spouse might hire separate divorce lawyers and battle over details or hire a mediator and work together on an agreement. Randi Albert, the New Jersey mediator, says some couples litigate part of their settlement and use a mediator to work through less contentious issues.

Also important to know: Nine states—Arizona, California, Idaho, Louisiana, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin— have community property laws that dictate an even split of all assets and debts built up during the marriage. Other states call for a fair and equitable split that considers factors like each spouse’s earning potential and contributions, such as child-rearing. Those rules apply if a couple hasn’t worked out their own property agreement before getting to court.

“People are more likely to follow an agreement that they’ve developed on their own, as opposed to one that was foisted upon them by the court,” Albert says. “So if you have the kind of relationship dynamic that allows you to work together, it’s definitely the way to go.”

Fairly dividing assets isn’t easy though. “It’s really not advisable to just put numbers on paper,” Seeber says, and decide, for example, that one spouse will take a house valued at $1 million and another will take investments valued at $1 million. You need to consider home maintenance costs and the tax hit you might take after an eventual sale, she says. If your money is tied up in a home, will you have cash available when you need it? Will you have enough credit to borrow in the future? If you are receiving an investment account, are proceeds taxable, or not? “You have to run the long-term projection to be able to say that, in 10 years, you really still are equal,” Seeber says.

Albert and her partner, family therapist Michele Weinberg, say they encourage divorcing spouses to run draft property agreements past separate financial advisors as well as separate attorneys.

Weinberg cautions that some gray divorcees will need to work years longer or go back to work after retirement to pay alimony or cover new living costs. “Sometimes, people who have never worked or have worked in a limited way now have to find a full-time job,” she says.

Couples who own a business together will face additional challenges. Will the business be sold, bought out by one spouse, or reorganized with two ex-spouse owners? The last is a fraught situation most people reject, Weinberg notes.

Divorce typically also means reconsidering everything from wills to plans for long-term care. Someone who expected a spouse to care for them in their later years will now need other options. That might mean moving in with a friend or jump- starting a move to an over-55 or assisted living community, says Eggerss.

Frank, the Florida divorcee and author, says she’s been able to stay happily single in her own apartment. She’s doing just fine now, she says. But she does share this advice for anyone going through a late-life divorce: “A second pair of eyes and ears, even from a trusted friend, can save you time, money, and grief. Don’t sign or agree to anything without having someone else review it.”

An ancient art form around the world, calligraphy has stood the test of time. What began as a way to preserve historical and religious texts has become a form of personal expression now used in everyday life.

From diplomas on sheepskin to elaborate wedding invitations on heavy card stock, calligraphy has elevated the look and feel of documents and paper products for centuries.

The precision of calligraphy’s nib-to-ink process is part of its allure. “The basic definition of calligraphy is just beautiful writing,” says Carole Murray. Murray owns and operates a custom calligraphy business, Calligraphy by Carole, based in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. In recent years, demand for calligraphy services has grown rapidly across the country, with thousands of professional calligraphers now creating art and products in their own distinct styles.

Murray’s interest in calligraphy was first sparked in the 1980s when she wanted to address the envelopes for her wedding invitations. But it wasn’t until 2008 that she turned her hobby into a full-time job, focusing on the wedding industry. Murray offers products ranging from table numbers and place cards to invitations and large signage. Her work is based on the copperplate style, a method of writing that has existed for centuries.

If you’re learning calligraphy today, it is likely based on the copperplate script. The writing instrument—a nib—is dipped in ink and then whisked, dragged, or flicked across the page as necessary to achieve the desired effect. The fundamental techniques are upstrokes and downstrokes, which work together to create the shape and width of each letter.

Murray describes her process: “I use a pointed pen nib that fits into an oblique holder. I dip the nib into calligraphy ink. When I apply pressure on my downstrokes, the slit in the nib will open and separate the two tines, allowing the ink to flow out thicker. When I don’t apply much pressure— typically on the upstrokes—the lines are thinner.”

Something for Everyone

Another, perhaps more approachable, style is modern calligraphy, which some say requires less precision. Modern calligraphy can also be described as loopy calligraphy. Jess Perelle, owner of Letter and Ink in Los Angeles, California, uses this style in her full- service design studio. “Modern calligraphy is a more casual, free-form version of calligraphy,” she says.

Perelle has always been an artist and dates her interest in calligraphy all the way back to middle school. “I started a little business, writing people’s names in Crayola marker,” she says. “I do that now, but the fancy version.”

Today, her design work includes custom drawings, wax seals, and letterpress designs. Perelle is self-taught from the comfort of her coffee table through a combination of online videos, classes, and ample practice.

A Sense of Nostalgia

In part, calligraphy’s growing popularity may be attributed to a sense of nostalgia and society’s enduring feelings of delight around physical objects. In an increasingly digital world, it still feels good to turn the pages of a book or receive a handwritten note.

“When you get your mail, aren’t you looking for something that’s handwritten first?” says Murray. “People still like anything handwritten. If it’s written in calligraphy, that is even better.” Handwritten items carry a sense of human connection that printed materials cannot emulate.

Maghon Taylor of All She Wrote Notes, a calligraphy studio and classroom in Gibsonville, North Carolina, felt a similar connection when she inherited a calligraphy set from her grandmother. “I had always loved doodling and handwriting, so I wondered if I could learn. I signed up for a calligraphy class, and I was not good at all!” she says.

Taylor strayed away from the traditional copperplate style and practiced at home in her own way. She found the most joy and success in hand lettering, a whimsical style she has coined faux-ligraphy. With hand lettering, there’s flexibility to use pointed-tip markers in lieu of the traditional nib and ink, plus options to write on unconventional materials—like chalkboards, holiday ornaments, or signage—in addition to paper.

Handwriting and lettering can be just as much of an heirloom as jewelry or other possessions. “In a world where everything is text and email and digital, handwriting is such a legacy,” says Taylor. The market for reprinting and preserving the handwriting of loved ones has expanded rapidly in recent years. On sites like Etsy, you’ll find custom products that can include your loved one’s handwriting etched into jewelry; printed on tea towels; burned into cutting boards; or featured prominently on scrapbooks, ornaments, bags, coffee cups, and more.

“If I could have anything of my grandmother’s, it would be something with her handwriting,” says Taylor.

Just Put Pen to Paper

Taylor turned her interest in handwriting into a career. She now teaches classes in person and virtually, has written four books about calligraphy, and sells products of her own design through Walmart stores nationwide.

But calligraphy doesn’t have to be your passion to be fun and impactful, Taylor says. She encourages her students to simply start somewhere and get back to handwriting. “Don’t worry about perfection; just start writing again,” she says.

Especially for those who may be worried about shaky hands or handwriting changes that sometimes come with aging, hand lettering can be a more forgiving technique than the nib-and-ink approach. After all, a handwritten note is a treasure no matter what the writing looks like.

Also, handwriting is good for the brain. A study from the University of Tokyo suggests, “The act of physically writing things down on paper is associated with more robust brain activation in multiple areas and better memory recall.”

Murray agrees. “Your hand, after all these years, still knows what to do,” she says. Sometimes, the action of handwriting and modern calligraphy can even feel meditative.

“It’s really not like writing; it’s like drawing letters,” Murray says. “You get into a rhythm when you write, and it’s very therapeutic.”

These days, there are thousands of online classes available across the country, and most major cities have calligraphy groups that meet in person to practice together. Writing place cards for a dinner party and addressing an envelope to a friend are two simple ways to get started.

“Who doesn’t love to see their name written beautifully? It’s just a special touch,” says Murray. And it’s one that has endured for centuries.

At the heart of this détente was the concept of mutually assured destruction, otherwise known as MAD, an appropriate acronym for the idea that should one of the then-superpowers launch a military attack or invade a sovereign nation, the other would retaliate with an all-out nuclear strike. And, of course, that strike would be followed by another retaliation, creating a cycle of destruction so dire that neither side would dare to start it.

The Day After

Thankfully, the Cold War came and went without MAD. Nonetheless, growing up during the Cold War meant that you lived with the constant overhang of nuclear war. This was made real to American citizens by duck-and-cover air raid drills at school, signs denoting fallout shelters intended to house survivors in the event of nuclear war, and myriad science fiction dramas, such as Dr. Strangelove, A Boy and His Dog, and the made-for-TV movie The Day After.

The Day After portrays a superpower skirmish over Germany that escalates into a full-scale nuclear war. The story is told through the eyes of regular Americans as they experience the bleak aftermath of a nuclear exchange. More than 100 million people watched the film during its initial broadcast on November 20, 1983, which made it the highest-rated television film in history, a record it held for more than 25 years.

Of course, we no longer have the Cold War in its original format, but we have since written or produced the end of the world countless times via movies, television series, and books. Let’s face it; humans are good at catastrophic thinking.

No Nukes Needed

Catastrophic thinking—or catastrophizing—occurs when you imagine that the worst possible outcome will occur in a situation with little basis in fact or reason, according to the American Psychological Association (APA). Sometimes, that imagined outcome results from a choice you have made. It’s a type of cognitive distortion we all experience at one time or another. Catastrophic thinking is part of being human.

It doesn’t take the threat of nuclear holocaust to set us off. It can start with a small thought that escalates rapidly, leading to stress and anxiety. In turn, this anxiety may cause you to react impulsively or keep you from reacting when action is required. At the very least, it creates worry.

Catastrophic thinking takes many forms. It happens in small ways when we are hours from home and wonder if we closed the garage door, when we text a friend and don’t get an immediate reply, or when we make a mistake at work. It happens in big ways as we absorb the news of the day: the 9/11 attacks, the financial crisis, or war in Ukraine.

In any case, thanks to our ancient ancestors, our brains are experts at extrapolating inputs into their worst-case outcomes. When early humans were wandering the savannas, underestimating what was rustling in the bushes ahead could be deadly. As a result, evolution has endowed us with survival instincts when faced with uncertainties, big and small. Sadly, some of these instincts are ill-suited to modern life.

Time Traveling

The financial version of catastrophic thinking comes in many flavors. A recent economic downturn may fuel fears of being laid off. Loss of a big client may make you feel like your job is in jeopardy. A market pullback or concerns about the future of Social Security may make you question if you’ll ever be able to retire. Worry and fear about money issues like these can lead to stress, insomnia, and depression.

A common theme is time travel—these catastrophes exist in the future—so the first step to heading off catastrophic thinking is to stop leaping ahead and focus on what is true right now. Here are four tips to help you manage your catastrophic thinking when it arises.

Replace fears with facts. It’s impossible to be reasonable when you’re in a state of fear, so shift your thinking to your rational brain. “Ignore the mass media,” says CAPTRUST Senior Director and Portfolio Manager Jim Underwood. “You can always find what you’re looking for, so you’ll likely find plenty to support your fears there. Instead, engage experts, read up on the topic, or talk to a trusted friend about your fears.”

Look at the worst-case scenario using data from the past to inform what you think might actually happen in the future. You should quickly find that, while possible, your worst fears are highly improbable. “The fact is, and history supports this, the worst outcome we think about is also the least likely to occur,” says Underwood.

Explore the in-between. Catastrophizing is a form of binary— that is, either/or—thinking. And human nature inclines us to focus on and worry about the negative possible outcomes more than we relish the positive ones. Instead, explore all possible outcomes: bad (but informed by facts!), good, and in-between.

Ask yourself: Is this what I really think will happen? While the worst case could happen, what is most likely to happen? When you dig into the most likely outcome, you may be relieved to find there is much to like about it. It may be much closer to the best-case than the worst-case scenario.

Take appropriate action. We don’t rule the world around us, so catastrophic thinking is often enhanced by a fear that we might end up as victims of forces that are beyond our control. This fear can drive us to take action as a way to feel better and regain a sense of control.

“When and if you feel this urge, make sure that you are not acting rashly,” says Underwood. “Make sure that your actions are based on facts rather than emotion. In reacting to the worst case, you don’t want to make an all-or-nothing decision that closes you off to the best-case or most likely scenarios.”

Live and learn. While you may worry or engage in catastrophic thinking, you are not alone. It’s part of the human condition, not a mental disorder. Our brains are unique tools that have given us many advantages. They also carry baggage from a simpler but much more dangerous time. When you feel yourself slipping into a mental catastrophe, take note, call a time-out, and let yourself off the hook.

“In the end, rather than catastrophizing, it’s important to focus on controlling the variables we can control,” says Underwood. “That includes using data to inform our thinking and trying to manage our emotional state. Things rarely turn out as bad as we fear, so it doesn’t make sense to lose sleep over them.”

How bad could it be, after all? It’s not like the world is going to end.

“I did not have any intention to foster,” says Sanders, an independent consultant in Raleigh, North Carolina. “It was not on my radar at all.” She had never been a parent, foster or otherwise.

But some friends had encouraged her to volunteer with a youth group. Some of the kids were from unstable family situations, and the activities provided them with a respite. “They needed me, and the people steering me to it thought I needed it too,” she says.

Immediately, she felt a sense of purpose, helping teenagers and finding out about their circumstances. In particular, she hit it off with one boy, Mark, a teen who seemed to have adult-sized burdens on his shoulders. He was staying in a temporary foster home with his younger sister, Maddie, and was also trying his best to look out for his mother, who was struggling with issues of her own.

Sanders saw quickly that this young man deserved to have some lightness and joy and a chance to act his age. On a long drive to a camp in the mountains, “he just talked my ear off,” she says. “It was unusual that he had so much fun with me, and that was noticed. That’s how this whole thing started.”

Later, the group leaders asked Sanders if she would consider taking the siblings into her home, just for a couple of weeks, to help relieve pressure at their temporary living situation. More than that, if she was willing, these weeks could be a trial run to becoming their foster parent.

“It was a new endeavor to work with youth,” Sanders says. “I have been my own person for a long time. Now, helping teens become their own person is fascinating.”

Multiple Entry Points

People don’t often think of midlife and beyond as prime parenting years. But older folks, empty nesters, and retirees have a lot to offer to kids in need. Also, many baby boomers and generation xers feel a strong desire to give back. They may have more time, patience, and resources at their disposal than in the earlier stages of their lives. The idea of channeling some of that energy to help nurture children in distress can be appealing.

Sanders agreed to the trial period. She felt herself already falling for Mark and Maddie (not their real names)—and seriously considering turning her life upside down for them. She reasoned, “I’m in my late 50s, widowed,” she says. “I have no kids. I have means—not endless means—but it’s not going to hurt me. It’ll stretch me mightily, but these are good kids, and they don’t have any good options. They were going to be split up, and I couldn’t bear it. I didn’t want them stretched.” She soon realized she would take them.

Sanders attended many Saturdays of foster training conducted by county social workers, who also visited her home and checked personal references as part of their process. Since she already had a relationship with the kids through the youth group—what social workers call a kinship—the teens were able to live with her during her training period. “I’d mostly heard about people fostering who already had kids, raised and grown, but that ain’t the only way! There is no one path to all of this,” she says.

Where to Start

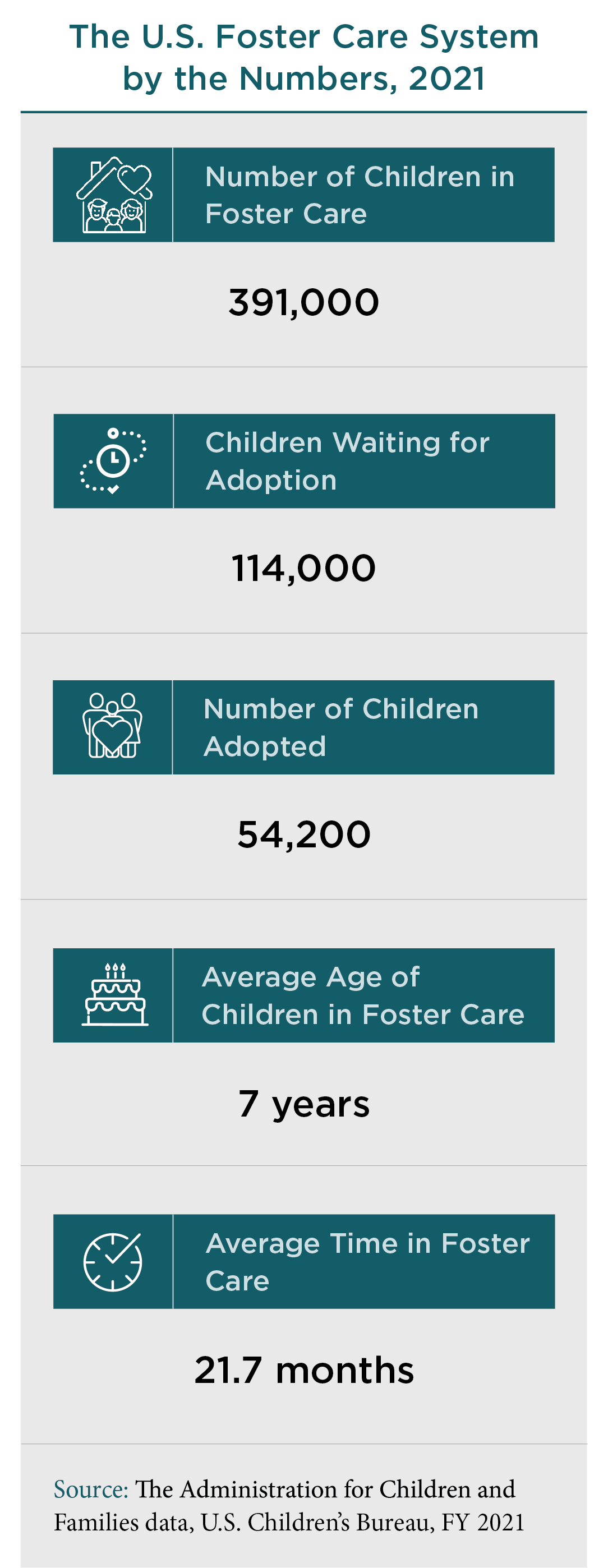

The U.S. child welfare system is notoriously complicated, and there is a perennial shortage of foster families. The need is great. In 2021, there were 391,000 U.S. children in foster care, according to the Department of Health and Human Services. At year-end, 54,200 children had been adopted out of the system, and another 114,000 children were awaiting adoption.

For parents and non-parents alike, fostering later in life has both challenges and rewards, especially considering that many kids enter the system after experiencing neglect or abuse in their youngest years.

The foster process varies by state and sometimes by county. Anyone who is exploring the idea of fostering can learn about the steps required in their community by reaching out to a local foster care agency.

A directory of state and local agencies is available on childwelfare.gov, the federal Child Welfare Information Gateway. There are also national agencies, such as AdoptUSKids, Casey Family Programs, and Kidsave.

The National Foster Parent Association has resources for online education and training. Generally, to become licensed, foster parents undergo 10 to 30 hours of training and complete interviews, a home inspection, medical exams, background checks, and financial assessments.

Sanders and the kids have been together ever since, including throughout the COVID-19 lockdown, when their world shrank to only three. It sometimes feels strange to her how deeply connected they became—and how quickly—in the house she had once planned to sell. Now there are dings on the walls, but she’s in no hurry to fix them. After all, she recently became legal guardian to the siblings, so “we will be here for a while.”

Sometimes, Sanders says she wonders what her late wife would think about her life now, her new family, and her role as a foster mom to two teens. It’s not a path that the two of them would have chosen together, she is certain. Her wife had a child already, one who is now a 32-year-old adult. “She’d been there, done that,” says Sanders. “This is my adventure, but I think she had a hand in it. I think she’s laughing.”

How would her wife have responded to the two teens? “I think she sent them,” Sanders says.

Q: What are digital assets, and what role do they play in estate planning?

A digital asset is any item or information that is stored electronically. Most commonly, this means your logins, passwords, PINs, and anything contained within an online account. What happens to these accounts when you die? The answer depends on the type of account and whether you have included its assets as part of your estate plan.

To add digital assets to your estate plan, start by making a list of all accounts. If you are already using a password management application, such as 1Password, LastPass, NordPass, or Keeper, a master list will be included as part of the service. Internet browsers can also show a list of saved logins and passwords. Check under settings and search for passwords.

Next, determine which accounts are valuable to you. Even if the asset has no financial value, its emotional significance might mean it’s worth saving. For instance, you may save your photo storage accounts and movie or music collections. In general, don’t bother creating plans for online shopping accounts, since these are likely to be deactivated on their own after a certain period of inactivity.

Most social media and email accounts have end-of-life provisions that can automatically transfer the account to a designated person after a specific number of days without access. But you must make sure you set these up.

For cryptocurrency, there are various digital asset inheritance services, such as Inheriti by Safe Haven and Covenant by Casa, that will guide your beneficiary through the transfer process.

Financial institutions do not recommend letting anyone else access your account using your credentials, whether you are dead or alive. Usually, your spouse or executor will simply need to contact the company and let them know you are deceased to begin the closure process. All financial accounts, including credit and debit cards, should be shut down soon after death to prevent fraud.

One digital asset worth preserving: Your frequent flyer accounts. Most airlines will transfer miles to a spouse or child.

As part of your estate planning, you will want to designate a specific person and provide them with authority to manage your digital assets. However, this does not mean you should include your passcodes or other access information in your will. When you die, your will becomes a public document, which means anyone can read it.

One solution is to reference an outside document in your will that contains all the necessary information to settle your digital estate. This way, you can continue to revise and update the outside document without having to either change your will or put your digital assets at risk.

By including digital assets as part of your estate plan, you make things easier for your loved ones, who would otherwise be responsible for tracking down and managing these accounts.

Yes, it means getting organized now, but doing so will protect you both in the short term and long after you are gone.

Q: Last year was challenging for my fixed income investments, but I hear 2023 might be a good time to buy bonds, specifically municipal bonds. Is that true?

From an investment perspective, 2022 was a wild ride. Just as quickly as interest rates rose, bond prices fell. You probably saw the headlines that said fixed income isn’t working anymore. Now, the same media outlets are saying it’s a good time to invest in bonds. At first, those comments may seem at odds, but the truth is that they’re intertwined because 2022 market conditions created an attractive environment for future returns on bonds.

As with most areas of investing, deciding if tax-exempt municipal bonds are a good fit for your portfolio will depend on your unique circumstances. However, for those who are considering buying bonds, it may be helpful to understand what makes an attractive municipal bond environment. In 2023, tax-exempt bonds, such as municipal bonds, may offer a compelling opportunity for four reasons:

- Attractive yields. The yield on any bond is the expected return on investment over its remaining life. Today, both tax-equivalent yields and overall yields on core municipal bonds are near decade highs.

- Improved financial conditions. Historically, credit defaults on investment-grade municipal bonds are exceptionally low. In the past few years, many municipalities have further strengthened their financial positions, accumulating cash reserves through federal stimulus programs and robust tax collections.

- Increased demand. With a divided Congress, significant changes to individual tax rates are unlikely. The combination of stable tax rates and improved credit fundamentals is likely to increase investor demand for tax-exempt municipal bonds.

- Limited supply. Typically, the supply of new municipal bonds is driven by entities that are refinancing existing debt. With the recent surge in bond yields, refinancing is significantly more expensive, thereby limiting the overall supply of bonds. Also, with increased cash reserves, municipalities may choose to delay additional capital raises in hopes of lower future rates. While there will always be exceptions to every rule, in this case, most investors are likely to be rewarded for locking in decade- high yields for the foreseeable future, even if the journey remains a little bumpy.

Q: I am the primary financial decision maker in my household. How do I encourage my spouse to be more engaged in our finances?

When it comes to financial matters, having two informed and active partners is almost always better than one. You’ll make stronger decisions, and you can ensure that neither of you ends up lost or overwhelmed with financial business when the other partner is disabled, is incapacitated, or dies.

It is common for spouses to have different financial personalities—for instance, different perspectives on spending, philanthropy, or risk. You don’t need to be completely aligned to have a unified financial life. What’s more important is that both people participate in reaching decisions. Here are a few steps you might consider to get your partner more engaged.

First, let them know why you want their involvement and perspective. Think of your financial life as a road trip. You will only need one driver at a time, but it’s helpful when the person in the passenger’s seat knows where you are headed and can be excited about it. If your partner can also help you navigate the turns, that’s even better.

If you don’t have a will, this can be a great first step to take together. Developing a will and an estate plan often involves dozens of decisions that will jump-start conversations about financial goals and desires. For instance, do you both have contact information for your tax, legal, and financial advisors? Does your spouse know the access code for your phone and where the keys to your safe are located?

It’s common for the less-engaged spouse to feel embarrassed, frustrated, or overwhelmed at first. Be patient as your partner learns the ropes.

You may also want to consider a similar process with your adult children and parents. By handing over financial knowledge before it is truly necessary, you can minimize emotional decision-making and avoid traditional pitfalls in the generational transfer of wealth.

It may be helpful to create a visual map of your financial life—including assets, accounts, and advisors—to illustrate how your money moves around and who else is involved in the process. Connecting family members with professional advisors is a critical piece of the puzzle, even if only by email.

And remember: Working as a financial team is like dancing together. For your partner to take a step forward, you’ll need to take at least a small step back.

SECURE 2.0: Investment and Fiduciary Issues

The widely reported SECURE 2.0 law includes more than 90 provisions, most of which pertain to retirement plan design and operation. As a point of reference, the first SECURE Act included only 31 provisions. A few provisions of the new law relate directly to fiduciary and investment issues.

- 403(b) plans, which are a close cousin to 401(k) plans, have not been permitted to use collective investment trusts (CITs). CITs have long been used in 401(k) plans for stable value investments, and CIT versions of traditional mutual funds are increasingly used in 401(k) plans to reduce investment expenses. The new law permits 403(b) plans to use CITs. Although the rule is effective as of December 29, 2022, this provision will not be available until corresponding changes are made in securities laws.

- Under current fiduciary law, when a plan participant is overpaid from plan assets, plan fiduciaries must take reasonable steps to recover the overpayment. SECURE 2.0 leaves recovery of overpayments to the discretion of plan fiduciaries. Under tax law, if the exact terms of a retirement plan are not followed, including overpayments to participants, the plan’s tax-preferred status can be challenged by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). The IRS has previously issued guidance providing some relief if overpayments are not recovered, and SECURE 2.0 codifies preservation of a plan’s tax-preferred status if overpayments are not recovered. Plan sponsors experiencing a situation like this should consult with their ERISA attorneys for guidance.

A few other aspects of SECURE 2.0 touch on topics that have been covered in earlier Fiduciary Updates.

- The penalty for not taking required minimum distributions (RMDs) has been reduced from 50 percent of the late distribution amount to 25 percent of the late distribution amount. This penalty is further reduced to 10 percent if the corrective distribution is made during a two-year correction window.

- The 10 percent withdrawal penalty for early retirement plan distributions will be waived for individuals with an illness that is reasonably expected to result in death within 7 years, per a doctor’s certification.

401(k) and 403(b) Fee Cases Continue

The flow of cases alleging fiduciary breaches through the overpayment of fees and the retention of underperforming investments in 401(k) and 403(b) plans continues but without significant new developments. Here are a few updates.

- Two of the approximately 10 cases alleging that it was a fiduciary breach to retain the BlackRock LifePath Index Funds have been dismissed and amended complaints have been filed. The challenged funds are an indexed target date series with a to-retirement design. Tullgren v. Booz Allen Hamilton v. Hall (E.D. Va. 2022); Hall v. Capital One Financial Group (E.D. Va. 2022).

- We previously reported on three Court of Appeals decisions dismissing fees suits because the initial claims did not sufficiently make a case that plan fiduciaries had breached their duties. District courts have applied the reasoning of these cases and dismissed other cases early in the litigation process. Nohara v. Prevea Clinic (E.D. Wis. 2022); Glick v. Thedacare (E.D. Wis. 2022).

- In a rare victory for a plaintiff in an ERISA fiduciary breach case, a judge in Connecticut has permitted a jury trial on some claims. Garthwait v. Evercore Energy Co. (D. Conn. 2022). Over the years, judges have written many pages on whether a jury trial is available in ERISA cases, with virtually all concluding no. Juries decide cases where the resolution would be legal, such as resolving an alleged breach of contract, and judges decide cases where the resolution would be equitable in nature. This is generally understood to be the situation with issues involving trusts, which fund retirement plans.

$750,000 Cybersecurity Loss Case Progresses with One Defendant Out

We have previously reported on a participant’s lawsuit attempting to recover more than $750,000 taken from her 401(k) account through cyber-fraud. The suit was filed against the recordkeeper, the plan fiduciaries, and the asset custodian/trustee, alleging various fiduciary breaches in making or allowing the fraudulent distribution. All three defendants filed motions to dismiss.

The asset custodian/trustee was released from the case, but the recordkeeper and plan fiduciaries were not. The court concluded that the asset custodian/trustee was not a fiduciary because it did not exercise any discretion or independent control over the plan or its assets. Its role was exclusively to follow the directions of others. This directed trustee role is different from the role discretionary common law trustees play in retirement plans, such as deciding which investments to offer in a 401(k) plan.

The judge noted that plan fiduciaries could be liable for the loss if they failed to reasonably select or monitor the recordkeeper. However, he observed that, “ERISA’s duty of care requires prudence not prescience. [Fiduciaries] must adopt reasonable procedures, but not absolutely air-tight procedures, to protect against the possibility of what happened here, which was a heinous crime.”

With respect to the recordkeeper, Alight, the court found that it may be considered a functional fiduciary but cautioned that it might not be. Under ERISA, a person or institution is a fiduciary if they exercise discretion or control over plan assets, regardless of whether they have been appointed as a fiduciary. The judge took the unusual step of recommending that the participant file a negligence suit against Alight. He went on to point out that the statute of limitations would run out in March 2023, concluding with, “the clock is ticking.” Disberry v. Employee Relations Committee of The Colgate-Palmolive Company (S.D. NY 2022).

Surprise! Ex-husband Inherits 401(k) Account Balance

A plan participant was divorced in 2002, and it was agreed that her ex-husband would have no claim to her 401(k) account. At that time, the ex-husband was the sole beneficiary. In 2008, the participant changed her 401(k) plan beneficiary from her ex-husband to her three siblings, with each to receive 33 1/3 percent. Unfortunately, the beneficiary designation form required that the allocation be in whole percentages. As a result, the beneficiary change was rejected.

In 2019, when the participant died, her $600,000 401(k) benefit was paid to her ex-husband. The participant’s estate sued the plan sponsor for breach of fiduciary duty in failing to correct the beneficiary designation form. At trial, it was revealed that, soon after the erroneous beneficiary designation form was submitted, the plan sponsor telephoned the participant and left a message notifying her of the error. The participant also received 11 annual account statements showing her ex-husband as the sole beneficiary. Award of the 401(k) account to the ex-husband was upheld at trial and on appeal. Gelschus v. Hogen (8th Cir. 2022).

Surprise! $24,000 Payment Resolves $2 Million Claim

An insurance company determined that it had overpaid a healthcare provider in Texas by more than $2 million through the payment of participant claims. The insurance company demanded repayment and months of discussions and correspondence ensued, but no agreement was reached. The provider eventually sent a letter and refund check for $24,000 to the insurance company.

The check included a notation saying it was in “full and final payment” of the repayment claim. Copies of the letter and check were sent to seven different addresses and individuals at the insurance company who had been involved in the negotiations. The physical check was sent to the insurance company’s lockbox where payments were received.

Five days after the letters were received by individuals at the insurance company, the check was deposited by the lockbox provider, and copies of the check and letter were scanned into the insurer’s tracking system. The next day, upon seeing the letter and check in the tracking system, an insurance company representative emailed the healthcare provider’s general counsel to reject the settlement offer.