-

Solutions

- Solutions

-

Individuals & Families

- Individuals & Families

- Individual Investors

- Executives & Business Owners

- Families with Complex Needs

- Professional Athletes

-

Retirement Plan Sponsors

- Retirement Plan Sponsors

- Corporations

- Educational Institutions

- Healthcare Organizations

- Nonprofits

- Government Entities

- Endowment & Foundation Leaders

- See All Solutions

Comprehensive wealth planning and investment advice, tailored to your unique needs and goals.Investment advisory and co-fiduciary services that help you deliver more effective total retirement solutions.CAPTRUST provides investment, fiduciary, and risk management services for nonprofit organizations. -

About Us

- About Us

- Our People

- Our Story

- Learn About CAPTRUST

-

Locations

-

Resources

- Resources

- Articles

- Podcasts

- Videos

- Webinars

- See All Resources

Becoming a parent is a life-changing adventure, one that can be fun, fulfilling, nerve-wracking, exciting, and overwhelming all at the same time. New babies often make us dream about the future, and we feel encouraged to make plans that will help ensure the best possible outcomes.

As you consider what your family’s future could look like, take time to evaluate your financial health. This financial checklist for new parents may be a helpful resource.

Health Care

- Review your deductible, co-pay, and maximum spending amounts for health insurance.

- Look to see what your policy year is (i.e., the 12-month period before your deductible, maximum spending, and other key metrics reset). If pregnancy and the child’s birth will occur in separate policy years, the timing could impact your out-of-pocket costs.

- Check if pregnancy and birth are covered under your existing insurance policy. If not, reach out to your insurance company to explore your options.

Tax Planning for the Year after Birth

- Learn about new tax deductions and credits and ensure your tax professional knows you had a child.

- Consider the child tax credit, dependent care tax credit, dependency exemption, flexible spending account (FSA), and medical expense deductions.

Foundational Planning (101)

- Edit your budget to include new monthly expenses that could be anywhere from a few hundred to a few thousand dollars. Beyond the universal pieces, such as diapers, clothing, food, and toys, some families may also need to account for childcare, increased doctor visits, medical expenses, and more.

- Consider setting up a savings account specifically for unexpected expenses, such as car repairs or home maintenance, with three to six months’ living expenses.

- Make a list of all your debts and put them in order of importance.

- Review insurance coverage to ensure you have adequate protection for your family, including insurance for your home, vehicles, potential disabilities, and long-term care.

- Review your retirement savings and make sure you are on track to meet your goals.

Next-Step Planning (201)

- Create or revise your estate planning documents, including a will to outline financial and parental guardianship if you and your spouse die prematurely.

- Set up a financial power of attorney to designate someone who can manage your financial affairs if you become incapacitated.

- Review your life insurance coverage to ensure your family has sufficient financial resources if something should happen to you.

- Consider an umbrella insurance policy to provide additional coverage for things like hosting large gatherings or having a pool or trampoline.

Education Savings

- Start saving for your child’s education as early as possible. There are several options for education savings, including a 529 plan, a Coverdell Education Savings Account, or a custodial account.

- Consider having family members and friends help fund the plan with regular gifts.

- Be aware of annual contribution limits.

- Remember that the primary benefit of education savings programs comes from their investment returns, so the earlier you start, the more opportunity for those returns to accrue.

Consult with your financial advisor for additional resources and help with planning.

According to a survey by the Funeral and Memorial Information Council, while 69 percent of American adults want to arrange their own funerals, only 17 percent have put plans in place. Regardless of your age, health, or financial circumstances, CAPTRUST Financial Advisor Christeen Reeg says, “creating a sketch for your own funeral is a smart decision.”

Yet most people don’t.

This inaction is likely because planning for death—or even talking about it with family and loved ones—is uncomfortable for most people. Brit Guerin, co-founder of Current Wellness and a licensed mental health counselor, says talking about death brings up emotions people don’t want to feel. “Talking about a loved one dying often feels taboo, in part because we don’t know what to say. It can bring up intense grief and sadness that are difficult to put words to.” Planning a funeral means accepting death.

But planning also makes death easier for your loved ones to navigate. And, it ensures your life will be celebrated according to your own thoughtful decisions, not the emotional and often rushed decisions of your grieving family.

Plan the Funeral You Want

“It’s important to know in advance what your loved one’s desires are,” says Guerin’s colleague and professional grief counselor, Monica Money. “Many times, family members want to do something different, even if the one who is dying has expressed their plans. That is why it is so important to have your wants and desires put in writing and kept in a safe place.”

When making arrangements, plans can be as general or specific as you like. Things like burial plots, service music, reception locations, and pallbearers can be finalized ahead of time. If you are fond of certain jewelry or clothing items, you can even choose what you will wear in advance.

Financial Advisor Christeen Reeg has personal experience with meticulous funeral planning. “When my husband became terminally ill, we were more comfortable talking about plans,” she says. “We selected a burial plot for both of us, and he planned things like service music, scripture, and even what the pallbearers would wear.”

One easy way to get started is to work with your local funeral home to decide what you want. Having a plan ensures your wishes are honored after you are gone.

A few practical questions to consider when you start planning are:

- What are your main concerns when it comes to your funeral?

- How much do you want to spend?

- Do you want to be buried or cremated?

- What would you like to happen to your remains?

- Where will your service be? What is the décor?

- What type of music do you want played?

- Who would you like to be involved in the service?

Keep the Peace

Having a clear plan to follow eliminates a few of the many difficult decisions your loved ones will have to make after you pass. Instead of having to sort through the details of where your service will be, how you will be buried, and what the ceremony will look like, they can simply follow the plan you have left them.

When Reeg’s husband died, she and her extended family viewed his pre-arranged funeral plans as a gift. “We had been married a long time, but we both had children from different families,” says Reeg. “At the time of his passing, we all met together. Not everyone was thinking the same. But I was able, as the surviving spouse, to pull out the document and say, ‘Well, this is what we agreed to and is already paid for. This is what your dad wanted.’ And so we didn’t have any fighting.”

It’s a natural human tendency to avoid the inevitable, and funeral planning can be an emotional process. But planning now reduces emotional flare-ups later. “It’s emotion that drives us, and it drives people to argue and fight,” says Reeg. “The greatest reason that I tell my clients to engage in funeral planning and put their plans in writing is that it’s going to reduce emotional conflict.”

Talking with your loved ones about these plans might feel awkward at first, but you will grow more comfortable discussing the topic over time. And they’ll most likely thank you when the time comes to put your plans in action.

While you don’t necessarily need to share funeral specifics with your family up front, it’s a good idea to disclose the fact that you’ve made plans, who you have left them with, and how to access them when you pass away. “Albeit challenging, openly sharing end-of-life plans can help normalize death and make it feel less scary,” says Guerin. “Grief is never easy, but knowing your loved one’s wishes can be very meaningful and special.”

Planning also helps prevent family members from overspending out of guilt or grief. “For example,” says Reeg, “what if all you want is a basic casket, but when your loved ones are emotional and grieving, they feel guilty and buy the $20,000 one?”

Marta Warren worked in the funeral insurance industry for decades. She says planning is a gift to yourself as well, and it’s never too early to start. “If you believe that you’re going to die at some point in your life,” she says, smiling, “then that’s the time to prearrange. I planned my funeral at a very early age, and I can modify it whenever I want to.”

Leave Plans with an Advocate

For safekeeping, Reeg says, in addition to your children or beneficiaries, it’s best to share your plans with your banker or financial advisor. “They are some of the first people your family will call when you pass,” she says. “I’ve been working with some of my clients for so long. I’ve been there for weddings and other milestones. And I’m there when someone in the family passes.”

Grief Counselor Megan Money says it’s also a good idea to have an appointed family liaison who will execute your plans. “Designate someone in the family who will follow through with your desires,” she says. The person you choose should be someone who will advocate for your plans and be able to separate their own emotions from the process as much as possible.

Warren equates funeral planning with estate planning. “It’s kind of like your will or your trust,” she says. Just as you manage your assets and plan for their distribution after you die, this is another step in the planning process. “When you’re doing your estate planning, it’s one of the things that your financial advisor should bring up.”

Peace of mind is the greatest benefit. “In my case, there was no fighting because all the decisions had been made,” says Reeg. “Making these arrangements in advance is such a gift that you can give your children. It’s so much more than a financial decision.”

If you give away money or property during your life, those transfers may be subject to federal gift and estate tax and perhaps state gift tax laws. The money and property you own when you die—also known as your estate—may also be subject to federal gift and estate tax and some form of state death tax. Additionally, these property transfers may be subject to generation-skipping transfer taxes.

To make the best financial decisions, it’s important to understand each of these taxes, which are governed by a handful of tax laws, including these four: the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001 (the 2001 Tax Act); the Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act of 2010 (the 2010 Tax Act); the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (the 2012 Tax Act); and the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. Recent Acts contain several changes that make estate planning easier.

The Federal Gift and Estate Tax: Background Information

Under pre-2001 tax law, no federal gift and estate tax was imposed on the first $675,000 of combined transfers. The term combined transfers refers to all transfers made both during life and at death. At that point, the tax rate tables were unified so that the same tax rates applied to gifts made and property owned by people who died.

Like current income tax rates, gift and estate tax rates at this time were graduated. Under this unified system, the recipient of a lifetime gift received a carryover basis in the property received, while the recipient of a bequest—a gift made at death—received a step-up in basis: an adjustment in the cost basis of the inherited asset to its fair market value on the date of the gift-giver’s death.

The 2001 Tax Act, the 2010 Tax Act, the 2012 Tax Act, and the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act substantially changed this tax regime.

The 2001 Tax Act increased the applicable exclusion amount for gift tax purposes to $1 million through 2010. The applicable exclusion amount for estate tax purposes gradually increased over the years until it reached $3.5 million in 2009. The 2010 Tax Act repealed the estate tax for 2010 and taxpayers received a carryover income tax basis in the property transferred at death, or taxpayers could elect to pay the estate tax and get the step-up in basis.

The 2010 Tax Act also re-unified the gift and estate tax and increased the applicable exclusion amount to $5,120,000 in 2012. The top gift and estate tax rate was 35 percent in 2012. The 2012 Tax Act increased the applicable exclusion amount to $5,490,000 in 2017 and the top gift and estate tax rate to 40 percent in 2013 and later. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, signed into law in December 2017, doubled the gift and estate tax exclusion amount and increased the gift and estate tax exemption to $11,180,000 in 2018.

The Current Federal Gift and Estate Tax

In 2023, the gift and estate tax exemption—also known as the unified credit—is $12,920,000, up from $12,060,000 in 2022. After 2025, the gift and estate tax exemption rate and gift and estate tax exclusion amounts are both scheduled to revert to pre-2018 levels, cutting the amount in half to roughly $6 million.

However, many transfers can still be made gift-tax free, including:

- Gifts to your U.S. citizen spouse

- Gifts up to $175,000 to a noncitizen spouse

- Gifts to qualified charities

- Gifts totaling up to $17,000 to any one person or entity during the tax year, or $34,000 if the gift is made by both you and your spouse and you are both U.S. citizens

- Amounts paid on behalf of any individual as tuition to an educational organization, or to any person who provides medical care for an individual

Federal Generation-Skipping Transfer Tax

The federal generation-skipping transfer tax imposes tax on transfers of property you make during life or at death to someone who is two or more generations behind you, such as a grandchild. It is important to note that the GST tax is imposed in addition to, not instead of, federal gift and estate tax.

You will need to be aware of the GST tax if you make cumulative generation-skipping transfers in excess of the GST tax exemption of $12,920,000 in 2023. A flat tax equal to the highest estate tax bracket in effect in the year you make the transfer (40 percent in 2021 and 2022) is imposed on every transfer you make after your exemption has been exhausted.

State Transfer Taxes

Currently, some states impose a gift tax, and others impose a generation-skipping transfer tax. Some states also impose a separate death tax, which could be in the form of estate tax, inheritance tax, or credit estate tax (also known as a sponge tax or pickup tax). Contact an attorney or your state’s department of revenue to find out more information.

Source: Broadridge Investor Communication Solutions, Inc.

If someone shouts at you to “stay out of the kitchen,” it either means they’re cooking a nice meal for you or—more than likely in 2023—you’ve joined the throngs of Americans having a smashing time on the pickleball court.

Pickleball, the whimsically named paddle game, is fast becoming everyone’s favorite addiction, er, pastime. In fact, it’s the fastest-growing sport in the country, with the total number of picklers reaching more than 5 million at the end of 2022—an increase of 40 percent since 2019, according to the Sports and Fitness Industry Association (SFIA).

Lately, pickleball has gotten lots of buzz from famous folks who love the game, including George Clooney, Leonardo DiCaprio, Bill Gates, and Kim Kardashian, and the pandemic-driven need to find outdoor activities didn’t hurt its popularity either.

Football legend Tom Brady is such a fan that, in 2022, he joined a bevy of superstar athlete-investors buying stakes in professional pickleball teams. High-profile names like LeBron James, Kevin Durant, and Maverick Carter are among those funding the expansion of Major League Pickleball (MLP). The budding MLP launched in 2021 with eight teams and has plans to grow to 24, with six professional tournaments scheduled for 2023.

A Mixing Pot

One of pickleball’s defining charms is its ability to bring people of different abilities and ages together for a fast-paced good time. It was this high fun factor that impressed David Damare, a mortgage lender and a former tennis player from Raleigh, North Carolina.

Damare says he has gotten into a habit of playing pickleball two or three times a week when he’s not traveling. He says the sport is silly yet serious, easy yet competitive, and highly accessible for all levels of players from professional athletes to octogenarians.

It’s a winning mix of attributes that draws the crowds. A park in Damare’s area recently converted two tennis courts to eight pickleball courts. Since then, he says, the courts are packed at all hours. “It’s all types of people, from couples in their early 20s and late teens all the way up to literally 80-year-olds that are playing,” he says. “That’s why you have to get there at 7:30 in the morning—because the retirees come at 8:00.”

“It’s a very equalizing type of game. Older and younger people can easily play together, and it can be competitive because you’re not trying to hit the ball as fast [as tennis],” Damare says. “It’s less about power and more about eye-hand coordination, which makes it more open to all ages.”

Once they tried it, Damare and many of his tennis buddies couldn’t stop playing, quickly accumulating a pickleball text group of 30 to 40 guys. “It’s not as hard on your body as tennis, but you do get a pretty good workout,” he says. “The ball is zinging back and forth, so your hand-eye coordination and keeping your head in the game are really imperative.” The community of picklers is welcoming to newcomers, and the mental focus the game requires seems to get people hooked.

Not So Serious

Pickleball hails from the Pacific Northwest. It was invented in 1965 by three friends—Congressman Joel Pritchard, Barney McCallum, and Bill Bell—on Bainbridge Island in Washington State. To entertain their kids, they patched together the first games with an assortment of paddleball, ping-pong, and badminton equipment and played on a badminton court with a hard plastic Wiffle ball.

With their families, they made up silly rules and terminology as they went along and took the name from one of their families’ pet dogs, Pickles.

Although pickleball is mostly a social game that doesn’t take itself too seriously, it can also be intense and competitive. Another thing that makes it highly accessible is that pickleball doesn’t require high levels of strength or athleticism since the 44-by-20-foot courts are much smaller than standard tennis courts. Also, the ball is surprisingly lightweight and is only served underhand, which requires less force.

Pickleball’s kitchen rule sets it apart from other racquet sports. Players get a fault if they step into the 7-foot rectangle next to the net, a zone called the kitchen or the non-volley zone, when volleying, which means hitting the ball without letting it bounce.

When serving, the ball is required to bounce once on the return and then bounce once again when it is hit back to the other side. After that, players can choose either to volley or hit the ball after a bounce. When volleying, they must stay out of the kitchen. Since players can’t play close to the net and keep smashing the ball from there, pickleball becomes more about placing the ball skillfully into intentional zones, rather than hitting it forcefully.

That makes pickleball the rare sport that can put a grandma in her 60s on a level playing field with elite athletes. And that’s not a metaphor—it’s a real-life event.

Last summer, Meg Burkardt, an attorney from Lawrenceville, Pennsylvania, joined a pickup game in the park with three young men she did not know. She could tell they were pickleball beginners and lent one of them her racquet.

After partnering with “the guy in the green shirt” and beating the pants off the other two, she learned that they were T.J. Watt, Minkah Fitzpatrick, and Alex Highsmith of the Pittsburgh Steelers defense. It was the crowd of spectators that had gathered that eventually tipped her off. The funny encounter went viral on social media after Burkardt’s daughter posted that “my mom whooped some Steelers in pickleball today lol.”

“These guys are so fast and so athletic and have really quick hands,” Burkardt told triblive.com. “Each game, they were getting exponentially better.”

Give It a Try

You don’t need much to get started in pickleball, just some paddles, some indoor or outdoor Wiffle balls, and a pickleball court. Any loose-fitting, comfortable clothing will do. Online vendors such as pickleballcentral.com, totalpickleball.com, and Amazon sell many inexpensive wooden or composite racquets that are suitable for beginners.

There are pickleball venues in every state. They’re often located in schools, parks, YMCAs, and community recreation centers. You can easily locate a court in your area by entering your zip code in the appropriate form on USA Pickleball’s places2play.org or by searching the Places2Play mobile app. Its database lists over 38,000 indoor and outdoor courts at nearly 10,000 locations.

The official rules are available online through USA Pickleball, but the best way to learn is just to visit a local court and give it a try. You can connect with potential practice partners by searching “pickleball groups near me” or joining Facebook pickleball groups. Soon enough, you’ll be the one yelling about the kitchen.

Pickleball Patter

A sampling of pickleball terms that may sound silly, but picklers take seriously.

- Kitchen: The non-volley zone, a 7-foot rectangle next to the net on both sides

- Pickled: Losing the game without scoring any points

- Dill ball: A ball in play that has bounced once and is inbounds

- Dink: A soft hit that lands just beyond the net, often in the kitchen

- Flapjack: A shot that must bounce once before it can be hit

- Erne: An advanced and often surprising shot that is hit from outside the court and usually close to the net (pronounced “Ernie”)

- Bert: Same as an Erne but on your partner’s side of the court instead of your own

- Volley llama: Illegally hitting a volley from the kitchen

On December 29, 2022, as a part of the government’s year-end spending bill, President Biden signed into law the SECURE 2.0 Act of 2022 (SECURE 2.0). SECURE 2.0 builds on the reforms included in the Setting Every Community Up for Retirement Enhancement (SECURE) Act of 2019, the most comprehensive changes to the U.S. private retirement system in over a decade.

On its way to the President’s desk, SECURE 2.0 carried support from both major political parties and both houses of Congress. This Act makes it easier for employers to sponsor retirement plans for their employees and easier for employees to save more for retirement.

Key provisions of SECURE 2.0 that affect retirement plans include the following:

- A mandatory increase in the required minimum distribution (RMD) age to 73 for those who attain age 72 between January 1, 2023, and December 31, 2032, and to age 75 for those who reach age 74 after December 31, 2032. The current RMD age is 72 for those who turned 70 1/2 after January 1, 2020.

- Increased catch-up contribution limit to the greater of $10,000 or 50 percent more than the regular catch-up amount for those ages 60 through 63. This is effective for taxable years beginning after December 31, 2024.

- Requirement that all catch-up contributions made after December 31, 2023, must be made as Roth contributions, with an exception for employees with compensation of $145,000 or less. The dollar amount is indexed.

- Removal of pre-death RMDs for Roth money held in employer plans, effective for 2024 RMDs.

- Modification of the Saver’s Credit to a Saver’s Match program. Taxpayers with qualified retirement contributions and who meet certain gross income requirements will be eligible to receive a government matching contribution of up to $2,000 to an eligible individual retirement account or retirement plan. Matching amounts will not count toward any annual plan contribution limits. This provision applies to taxable years beginning after December 31, 2026.

- An optional provision for employers to treat student loan repayments as elective deferrals for purposes of matching contributions. This allows participants to self-certify and receive a matching contribution to their retirement plan for qualifying student loan repayments made for plan years beginning after December 31, 2023.

- An optional provision for employers to offer an emergency savings account linked to a defined contribution plan for non-highly compensated employees beginning in 2024. Employers may enroll participants automatically into an emergency savings account at up to 3 percent of salary, up to a total contribution amount of $2,500. Contributions are made as Roth contributions, and employees participating may take tax-free and penalty-free distributions at least once per calendar month.

- An optional provision to offer an emergency savings distribution option of $1,000 per year that can be repaid to the plan, beginning in 2024.

- An increased small-balance automatic cash-out amount from $5,000 to $7,000, effective for distributions made after December 31, 2023.

- An optional provision for the employer to allow participants the option of receiving matching contributions on a Roth basis, effective immediately.

- A required reduction in the long-term, part-time required years of service from three years to two years. The SECURE Act of 2019 previously required an employer with a 401(k) plan to permit employees with at least 500 hours of service in three consecutive years to participate in the plan. This provision would be extended to ERISA-covered 403(b) plans as well. It will be effective for plan years beginning after December 31, 2024.

- Creation of a new Retirement Savings Lost and Found database within two years to collect information on missing, lost, or nonresponsive participants and beneficiaries and to assist savers in locating their benefits.

Specific to 403(b) qualified retirement plans, SECURE 2.0 includes:

- Expansion of available investments to include collective investment trusts; however, this provision is not yet practicable without additional changes to U.S. securities laws.

- The option for 403(b) plans to join a Pooled Employer Plan (PEP) or a Multiple Employer Plan (MEP) beginning in 2023.

- Expansion of the contribution sources that can be used for a 403(b) hardship withdrawal to match those available to a 401(k) plan, effective for plan years beginning after December 31, 2023.

Specific to new qualified retirement plans, SECURE 2.0 includes:

- The requirement that all new 401(k) and 403(b) plans established after December 31, 2024, offer automatic enrollment and auto-escalation starting at a 3 percent minimum with a maximum increase to 15 percent. Governmental plans and church plans are exempt from this requirement, as are new businesses for the first three years in business and small businesses with fewer than 10 employees.

- Increased start-up plan credits for small employers. It increases existing credit from 50 percent to 100 percent of qualified start-up costs for employers with up to 50 employees for the first three years after a plan is established. This includes an additional employer credit for employers with up to 100 employees based on eligible employer contributions. It also applies to new plans that join an existing plan, such as an MEP or a PEP. It is effective for taxable years beginning after December 31, 2022.

- A new Starter-K retirement plan option available to small employers that offers a safe harbor from nondiscrimination and top-heavy testing requirements. Employers are not required to make contributions, and annual contributions would be limited to $6,000. Employees must be automatically enrolled at 3 percent of pay. This is effective for plan years beginning after December 31, 2023.

Specific to defined benefit retirement plans, SECURE 2.0 includes:

- Direction to the Treasury Department to update the mortality tables used to determine minimum funding rules for valuations, beginning with valuation dates in 2024, within statutory limits.

- Updates to the notice and disclosure requirements with respect to lump-sum distributions.

- Clarification that the projected interest crediting rate for cash balance plans shall not exceed 6 percent.

- An extension of the ability of an employer of an overfunded pension plan to use assets to pay for retiree health and life insurance benefits to December 31, 2032. This permits transfers to pay retiree health and life insurance benefits provided the transfer is no more than 1.75 percent of plan assets and the plan is at least 110 percent funded.

Plan amendments made pursuant to SECURE 2.0 must be made on or before the last day of the first plan year beginning on January 1, 2025 (or 2027 for governmental plans). Plan amendments made pursuant to the SECURE Act of 2019 and the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES) are also updated to match these dates.

Should you have immediate questions, or for more information, please contact your CAPTRUST financial advisor at 1.800.216.0645.

On December 29, 2022, as a part of the government’s year-end spending bill, President Biden signed into law the SECURE 2.0 Act of 2022 (SECURE 2.0). You may have heard about this Act in the news. SECURE 2.0 builds on the reforms included in The Setting Every Community Up for Retirement Enhancement (SECURE) Act of 2019.

With support from both major political parties and both houses of Congress, SECURE 2.0 makes it easier for employers to sponsor retirement plans for their employees and easier for investors to save more for retirement.

Of note, there are several changes related to required minimum distributions (RMDs), some of which can impact distribution requirements as soon as next year:

- The required minimum distribution (RMD) age will be increased to 73 for those who attain age 72 between January 1, 2023, and December 31, 2032, and to age 75 for those who reach age 74 after December 31, 2032. (The current RMD age is 72 for those who turned 70 1/2 after January 1, 2020.)

- All catch-up contributions made after December 31, 2023, must be made as Roth contributions (with an exception for employees with annual compensation of $145,000 or less). The dollar amount is indexed.

- Pre-death RMDs for Roth money held in employer plans will be removed, effective for 2024 RMDs.

- Roth 401(k) RMDs will go away beginning in 2024.

- Penalties for missing a RMD will be cut in half beginning in 2023. The penalty will be reduced from 50 percent to 25 percent and, if the omission is corrected in a timely fashion, reduced to 10 percent.

Additional key provisions of SECURE 2.0 that may impact individual retirement savers include the following:

- The catch-up contribution limit will be increased from $6,500 to $7,500 for those between the ages of 50 and 59 and to the greater of either $10,000 or 50 percent more than the regular catch-up amount for those aged 60 through 63. This is effective for taxable years beginning after December 31, 2024.

- The allowance for tax- and penalty-free rollovers from 529 education saving plans to Roth IRAs is limited to $35,000, and beneficiaries must move the funds to a Roth IRA in their name. The 529 must have been opened for more than 15 years.

- Qualified charitable distribution limits will increase. The current $100,000 limit will be indexed for inflation starting in 2023, and the Act will also permit one-time gifts of up to $50,000 via a charitable trust or gift annuity.

- Employers will have the option of treating student loan repayments as elective deferrals for purposes of matching contributions. This allows participants to self-certify and receive a matching contribution to their retirement plan for qualifying student loan repayments made for plan years beginning after December 31, 2023.

- A new Retirement Savings Lost and Found database will be created within two years to collect information on missing, lost, or nonresponsive participants and beneficiaries, and to assist savers in locating their benefits.

- The small-balance automatic cash-out amount will increase from $5,000 to $7,000, effective for distributions made after December 31, 2023.

- Employers will have the option of allowing participants to receive matching contributions on a Roth basis, effective immediately.

- All new 401(k) and 403(b) plans established after December 31, 2024, must offer automatic enrollment and auto-escalation starting at 3 percent minimum, with a maximum increase to 15 percent. Governmental plans and church plans are exempt from this requirement, as are new businesses for the first three years in business and small businesses with fewer than 10 employees.

- The Saver’s Credit will be modified to a Saver’s Match program. Taxpayers with qualified retirement contributions and who meet certain gross income requirements will be eligible to receive a government matching contribution of up to $2,000 to an eligible individual retirement account (IRA) or retirement plan. Matching amounts will not count toward any annual plan contribution limits. This provision applies to taxable years beginning after December 31, 2026.

Some of these changes will begin to impact retirement plan participants in 2023.

Should you have immediate questions, or for more information, please contact your CAPTRUST financial advisor at 800.216.0645.

On November 22, the Department of Labor (DOL) released its final rule designed to clarify a path forward for retirement plan fiduciaries wishing to incorporate environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors into their investment selection and monitoring process. The long-awaited rule, titled “Prudence and Loyalty in Selecting Plan Investments and Exercising Shareholder Rights” was originally proposed in October of 2021, months after an announced non-enforcement policy to the rule issued on October 30, 2020.

Once effective, this final rule will modify and reverse certain amendments to the Investment Duties regulation under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA). An early read of the final rule should allay the fears of many commenters to the 2021 proposed rule, as the DOL makes clear that fiduciaries may consider climate change and other collateral benefits when making investment decisions and exercising shareholder rights. However, there is no requirement to incorporate such considerations, as was the concern by many readers of the proposed rule.

Over the last approximately 40 years, the DOL has periodically provided plan sponsors with interpretive guidance on how ERISA’s fiduciary duties of prudence and loyalty apply to the selecting and monitoring of investments that promote ESG goals. The DOL’s use of non-regulatory guidance recognized that, under the appropriate circumstances, ERISA did not preclude fiduciaries from making investment decisions that took ESG goals into consideration in connection with an investment’s risk and return.

As discussed in a previous Plan Sponsor e.Brief, the October 2020 rule aimed to address perceived confusion about the implications of that guidance. However, in confirming that fiduciaries may only select investments based solely on the consideration of pecuniary factors, it discouraged many sponsors’ desires to integrate ESG goals.

In its final ruling, the DOL has aimed to reverse what the Assistant Secretary of Labor Lisa Gomez called the “chilling effects” from the previous ruling by creating space for the consideration of relevant collateral factors without tilting the scales in favor of ESG factors.

Among the many modifications and changes to the Investment Duties regulation, this final rule includes the following:

- A restated expression of ERISA’s duty of loyalty in the context of investment decisions, removing the previous rule’s standard of pecuniary factors only;

- A broader description of what factors a fiduciary may deem as relevant to a risk-return analysis, such as climate change and other ESG factors;

- Changes to the tie-breaker test, replacing previous provisions with ERISA’s statutory duty to act prudently;

- Clarification, with caveats, that fiduciaries of participant-directed plans do not violate the duty of loyalty because the fiduciary takes into account participant preferences;

- Removal of restrictions that disallowed a fund to serve as a QDIA if it included or considered the use of any non-pecuniary factors in its investment objective; and

- Removal of two previous proxy voting safe harbors that allowed sponsors to refrain from voting if they deemed the item to be immaterial or their plan’s position to be below a quantitative threshold.

With the exception of the rule’s proxy voting provisions, the amendments set forth will go into effect 60 days after its publication in the Federal Register.

Should you have immediate questions, or for more information, please contact your CAPTRUST Financial Advisor at 800.216.0645.

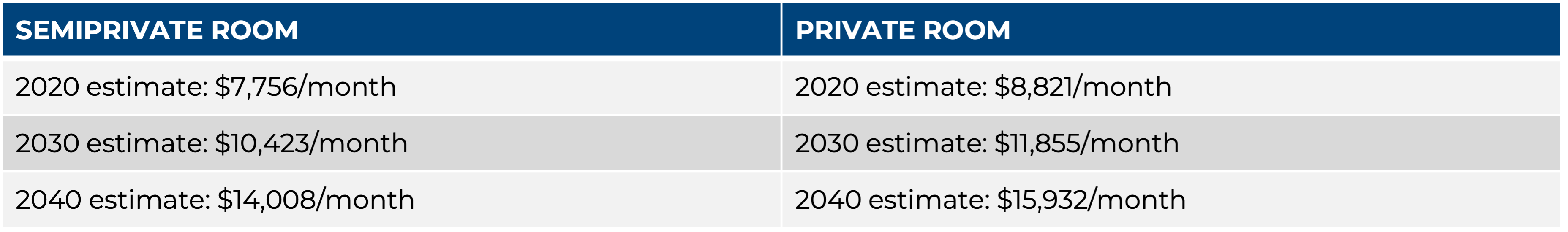

Long-term care typically refers to support that is required for an individual to perform the regular activities of daily living, such as dressing and bathing, due to a medical or mental condition. According to data from the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), 70 percent of Americans today will require some type of long-term care, and the average person will pay roughly $138,000 for their long-term care. Public programs and insurance will cover about half of these costs, but one in six people will still pay more than $100,000 out of pocket for long-term care expenses.

Almost everyone will qualify for Medicare coverage, and most people assume that it will cover all their health needs. But the truth is that Medicare covers health issues a person could possibly recover from or manage the severity of, like a broken bone, diabetes, or cancer. Medicare does not cover long-term care for permanent physical or mental limitations. In those cases, the individual is responsible for payment using their own resources. Another option is to purchase long-term care insurance.

Sources: 2020 Cost of Care Survey, Genworth Financial

What Types of Long-Term Care Exist?

There are three types of long-term care. All three types can be provided at home or in a dedicated facility, such as an assisted living center or continuing-care retirement center.

The first and most-used type of long-term care is custodial care. With custodial care, you receive help with daily living activities like eating, dressing, bathing, or getting around town. Custodial care is generally considered to be non-medical in nature. It can be provided by unpaid family caregivers or can be part of a paid service provided by home health workers or nurse aides.

One step up from custodial care is intermediate care. This is the term for health care that is provided by a skilled professional at regular intervals but usually on an infrequent basis. One example is weekly rehabilitative services.

The third type, called skilled care, involves 24-hour professional health care. Although many people associate skilled care with nursing homes, it may be provided at your own home, in an assisted living facility, in a hospital, or in other locations.

DHHS data shows that the average American will need three years of long-term care, including one year of paid care in-home and one year in a healthcare facility. Whether you plan to age in place or move to a retirement community, planning for the cost of your long-term care should be part of your larger financial plan.

How Will You Pay for It?

Medicare provides healthcare benefits for medical needs, including a percentage of some types of intermediate care and skilled care. It does not cover custodial care—the type of long-term health care that most individuals will need—even if a paid professional provides that care.

Medicaid, which is often confused with Medicare, is a joint federal and state healthcare program open to people with limited income and assets. Medicaid covers some long-term care but provides only limited coverage, and because of the income limit, the majority of Americans do not qualify for this program.

That means most people have two true options to fund their long-term care: pay out of pocket or buy long-term care insurance.

Is Self-Insurance a Good Option?

Paying out of pocket—also called self-insurance—is the most common way to pay for long-term care expenses. Self-insurance gives you the freedom and flexibility of full control over your long-term care decisions without having to consider what is covered or not covered by your insurance policy. When choosing this option, it’s important to understand the rising costs of long-term care and be sure you are making an intentional decision as part of your financial plan.

According to data from Genworth Financial:

- Home health aides currently cost $4,576 per month on average but may increase to $6,150 per month by 2030.

- Adult day care currently costs $1,603 per month on average but may increase to $2,154 per month by 2030.

- Assisted living currently costs $4,300 per month on average but may increase to $5,779 per month by 2030.

Note that the cost of long-term care will vary depending on the level of care you need and your location. You’ll find the least expensive long-term care in the country in Louisiana, West Virginia, Missouri, and Oklahoma. The most expensive markets for long-term care are in Connecticut, Alaska, New York, and New Jersey. The average cost of a private room in a nursing home in the Bridgeport-Stamford-Norwalk area of Connecticut, for instance, is nearly $160,000 a year. Equivalent care in Baton Rouge, Louisiana will cost around $57,000.

If you choose to self-insure, you’ll want to be confident that you have sufficient assets to pay the costs of care, no matter what. You may need to reallocate liquid assets, and you may face corresponding tax consequences. A financial advisor can help you plan and prepare for these moves.

What is Long-Term Care Insurance?

Long-term care insurance (LTCI) is specifically designed to pay for long-term healthcare in settings like nursing homes or in your own home. Essentially, LTCI enables you to transfer a portion of the financial liability of long-term care to an insurance company in exchange for regular premiums. But policies vary widely, so it is important to know what you want and choose a policy that aligns with your needs.

Most LTCI policies cover all three levels of care—custodial, intermediate, and skilled—so long as you are receiving them in a licensed nursing home. Some policies will limit or exclude additional settings, like home health care. Generally, long-term care insurance will also cover adult day-care centers, respite care, and other forms of health care provided by licensed and registered professionals, like physical therapists and nurses.

Comprehensive policies are more likely to cover home care services and assisted living, but also come with a heftier premium. Some comprehensive policies will cover the cost of personal care consultants and caregiver training for a family member or friend.

Before you can use your benefits, insurance companies typically require that you meet certain physical, social, or mental conditions. For example, you may need to provide proof that you can no longer independently perform regular daily activities, like bathing or dressing. All these requirements will be explained in your policy documents at enrollment.

According to 2020 data from the American Association for Long-Term Care Insurance, the average annual long-term care insurance premium for a 55-year-old couple was $3,050. Single males of the same age paid $1,700 a year, and single, 55-year-old females paid $2,650 a year. But prices for virtually identical insurance policies varied from $3,000 to $6,300 a month, which is why it’s important to do your research and make an informed decision. You might also consider working with an insurance professional who can help you compare multiple insurers and policies.

One benefit to LTCI is that it may help you minimize the financial impact of an extreme medical event or condition. As part of your financial plan, LTCI may be a piece of portfolio risk management or estate and legacy planning.

While there is no one-size-fits-all answer or obvious net-worth threshold that makes one option better than the other, there is a clear first step. Talk with your financial advisor about your needs, concerns, and desires. Having a plan in place will help you evaluate potential scenarios, stress-test your choices, and feel confident in your long-term care decisions.

Since health savings accounts (HSAs) first became available in 2003, they have been helping individuals covered under a compatible health plan, known as a high-deductible health plan (HDHP), become more engaged healthcare consumers who are better prepared for their healthcare expenses both now and in retirement.

HSAs can be used in a variety of ways to help manage current qualified medical expenses and also future qualified medical expenses even after employees retire. Unlike flexible spending accounts (FSAs), HSAs are not subject to the use-it-or-lose-it rule. And employees can actually sock away quite a bit of money annually in an HSA.

For 2022, the annual cap on HSAs is $3,650 for self-only and $7,300 for family coverage. Also, employees who don’t use the money can keep saving it in their HSA accounts. Once employees establish a cash cushion within their HSA to pay for short-term, unanticipated, qualified medical expenses and out-of-pocket maximum deductible limits, many have a large enough balance to begin investing in mutual funds, stocks, or bonds.

Ultimately, these programs empower employees as healthcare consumers. Because they are contributing more of their own money when they’re using an HDHP and an HSA, they are more involved in the cost of healthcare services, says CAPTRUST defined contribution practice leader Jennifer Doss. “Employees may be more inclined to consider the necessity of high-cost health care in certain circumstances; for example, an urgent care visit versus a visit to the emergency room.”

By enabling employees to choose when and how their healthcare dollars are spent, HSAs allow participants to decide what’s best for their unique situations. What’s more: HSAs offer savings and tax advantages that traditional health plans can’t duplicate.

HSAs are the only type of retirement account that is triple tax free. The money employees put in is tax free; the money employees take out for qualified medical expenses is tax free; and earnings on account balances are tax free. Further, because an HSA stays with the employee, not the employer, it’s very attractive to employees who are worried about paying for healthcare costs if they are furloughed, laid off, or simply want to move to a different organization.

Also, HSAs are growing. In recent years, enrollment has increased significantly with over 30 percent of workers covered under these plans, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. And, by some estimates, HSA-eligible health plan enrollment is projected to continue to grow by nearly 25 percent annually and is on pace to exceed 36 million enrolled in HSAs by 2023. In 2022, 63 percent of large employers offered an HSAs: a rise of 20 percent since 2018.

While the rapidly evolving HSA market undoubtedly points to improved spending and saving experiences for the employee, it also shows meaningful value for employers.

HSA Advantages for Employers

Since 2008, there has been a significant increase in employers offering HDHPs and HSAs. In 2020 alone, the percentage of employers that offer HSAs grew at a rate of more than 50 percent. According to the experts, the reasons are clear.

From reduced taxes and lower insurance premium rates to employee retention and increased flexibility for plan sponsors, the HSA is as much a savings gem for employers as it is for employees.

HSAs reduce taxes. When employers contribute money to their employees’ HSAs, 100 percent of those contributions are tax-deductible, Doss says. “A lot of employers contribute between $500 and $1,000 to the HSA for a participant to start out with.” Some employers choose to contribute a lump-sum payment, while others opt for periodic deposits.

When employees contribute to HSAs through payroll deductions, the contribution is made pre-tax, which saves both employees and employers on Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) taxes (7.65 percent each).

In other words, while employees are able to leverage the triple tax advantage HSAs offer, employers are also able to benefit from HSA tax advantages. Experts say the FICA tax savings for employers alone can be so substantial that many employers choose to increase their employer HSA contributions in order to maximize those tax savings.

HSAs reduce insurance premium rates. Used in conjunction with HDHPs, HSAs help employers save on health insurance premiums, says Doss. “As employees take ownership over their health and become more involved healthcare consumers, that often spills over to lower increases on annual premiums.”

Even with an employer contribution to employees’ HSAs, the overall cost for healthcare coverage is usually less because the premium rates on HDHPs are considerably lower than traditional health plans. In fact, the National Bureau of Economic Research indicates that employers who switched from non-HDHPs to an HDHP paired with an HSA saw a 10 to 12 percent decrease in firm-wide health spending in just two years.

HSAs improve employee retention. An employer contribution to = an HSA is a visible, valuable, and welcome addition to an employee’s total compensation package. “Because HDHPs and HSAs can help your employees save money and invest for the future in a way they can see, they’re a great addition to any benefits package,” Doss says.

In a survey of 1,200 employers, 50 percent said employee recruitment was a big part of their decision to offer an HSA, and 57 percent indicated employee retention as a driver. What’s more, those numbers increased by 100 percent from the year prior.

Garry Simmons, practice leader of health and group benefits consulting at Milliman says that uptick makes sense. “There’s such a war for talent right now. It’s so hard to find anybody who’s willing to work, for one thing. And then beyond that, it’s how do you keep them?” Simmons says offering an HSA helps employers “maintain a market competitive position and can aid in attracting and retaining top talent.”

Although not all employees will embrace HSAs, savvy employees who understand the benefits will value a program that includes an HSA. And employees appear to be getting more comfortable with the combination of an HDHP and HSA–especially younger employees.

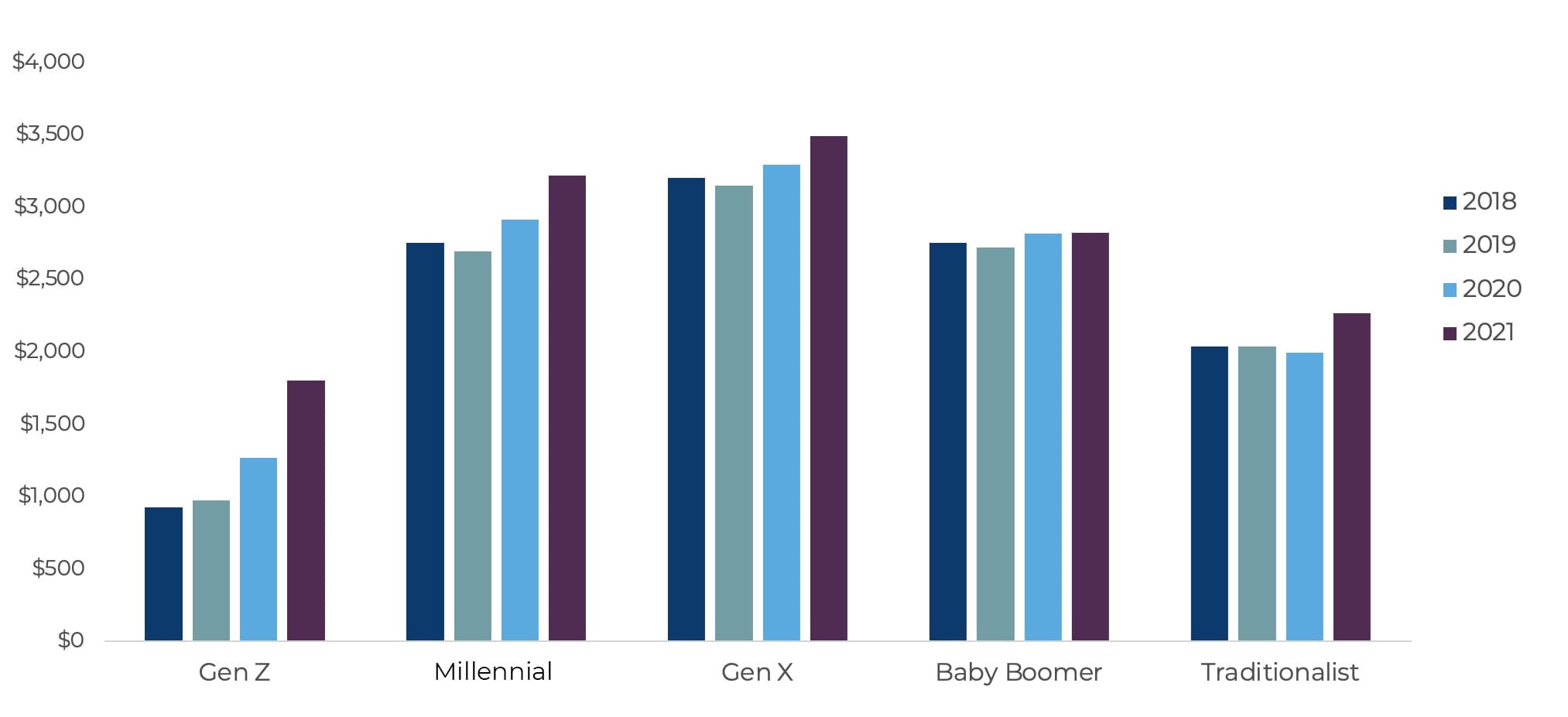

It’s these younger generations—Generation z, the millennials, and Generation x, which make up a combined 68 percent of the current labor force—who are responsible for the highest growth in HSA contributions since 2018, as shown in Figure One. Additionally, gen z employees nearly doubled their family HSA contributions since 2018, increasing contributions by 42 percent in 2021 alone.

Figure One: HSA Contribution Trends by Generation

Age groups used in this report: Generation z (born 1997 and after), millennials (born 1981-1996), Generation x (born 1965-1980), baby boomers (born 1946-1964), and traditionalists (born 1945 or before).

Source: “2” benefitfocus.com, 2022

HSAs support overall employee wellness. Fifteen months after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, a study by MetLife discovered even more reason for employers and plan sponsors to offer HSAs: They make a positive impact on workers who are shaken by the pandemic’s resulting financial uncertainties.

Simmons agrees. “An HSA certainly can help employees manage their medical finances and avoid what could be a catastrophic financial situation,” he says. If employees are stressing or they’re distracted by finances, they’re not as productive to the employer, he says. “As part of an overall financial well-being package, HSAs ultimately improve the productivity of a workforce, and [the employer] benefits from that.”

The study indicates that employees who owned an HSA felt significantly better about their financial wellness and were better able to manage stress related to their personal finances compared with employees without an HSA. Based on MetLife’s research, employees who owned an HSA were 22 percent more likely to say they felt better in general—physically, financially, mentally, and socially.

Additionally, companies offering HSAs find that employee healthcare choices and behaviors change dramatically, Doss says. “HSAs create a powerful reason for employees to want to stay healthy.” It’s the concept of consumer-driven healthcare, Doss says. “That means, with HSAs, employees tend to be more careful and inquisitive into their healthcare purchases because this is their money.”

HSAs improve employee retirement readiness. According to a recent report, healthcare costs have risen by 40 percent since 2015 and 5 percent in 2022 alone. In fact, according to HVS Financial, for a healthy, 65-year-old couple retiring in 2022, total costs for premiums and out-of-pocket expenses will average $683,306. Moreover, if this couple starts receiving Social Security payments at 65, healthcare expenses will consume 71 percent of their benefits, leaving far less than many might expect for other living expenses such as housing.

Sound stressful? It is. John Hancock’s 6th annual financial stress survey reports that saving for retirement is the most prominent cause of financial anxiety for employees. Specifically, respondents’ top retirement-related financial concern was putting enough funds away to cover the healthcare costs they’ll incur.

This stress doesn’t take a toll only on individuals, Doss says. “Employees struggling to effectively prepare for retirement can have a real impact on the health of a business through reduced productivity and increased employee absences.” Moreover, when workers are extending their employment into their senior years out of necessity, they can slow the promotion pipeline and consume a disproportionate share of the organization’s resources, Doss says.

Luckily, employers have a powerful tool at their disposal to help address these issues and give their employees peace of mind.

With its triple tax advantage, the HSA is a great way for employees of all ages to supplement their retirement savings while covering out-of-pocket health expenses, Doss says. “HSAs’ unique ability to avoid paying taxes on both contributions and earnings if used for qualifying medical expenses sets them apart from 401(k)s and IRAs and puts them at the top of the list for tax-efficient investment options for retirement.”

Better yet, at the age of 65, employees can use their HSAs to pay for any nonqualified medical expenses. As Simmons says, there’s always the long-term HSA advantage. “You’ve got money to pay for the expenses that Medicare doesn’t cover, or even premiums for Medicare supplement plans.”

Plan flexibility. A major strength of offering an HSA is program flexibility. “Like any other benefit, employers have the ability to go out and shop to decide what kind of HSA platform they want to offer,” Doss says.

HSA platforms differ in the types of investments offered, minimums required for investment, account accessibility, and overall fees, Doss says. Some platforms also offer education for employees and assistance with creating model portfolios. “Education here is key. Employers should consider offering resources to help employees look at ways to invest their money and reduce the difference between what they should have in short-term savings for everyday medical expenses versus that long-term retirement medical expense,” Doss says.

Another flexibility: The two cost components of HDHPs and HSAs—the HDHP premium and the employer contribution to employees’ HSA accounts—are independent and can be changed as needed. Flexible plan design means employers can adapt the plan options according to their changing business needs. For example, employers can partially fund their employees’ HSAs or pay for a percentage of HDHP coverage. They can also fully fund an HSA and pay for the HDHP coverage. Employers are using the flexibility of the HSA to reduce their involvement in benefits and share more responsibility with the employee.

Low administrative burden. Speaking of sharing more responsibility with the employee, given the individual account nature of HSAs, much of the administrative burden is switched from the employer (or paid third-party administrator) to the employee and the HSA provider.

From the employer standpoint, you’re engaging with an HSA provider to do the administration for you, Doss says. “Once the money goes into these individual HSAs, it belongs to the individual. The employer is not administering anything from the HSA perspective at that point.”

Experts agree: Employees are not the only ones who benefit from having an HSA. Employers can also realize savings through lower medical premiums, tax-deductible contributions to employees’ HSAs, plan flexibility, and more.

Employers not yet offering these accounts may want to explore their health plan offerings and consider incorporating an HDHP paired with an HSA. As offerings continue to expand, employers that are already offering HSAs may think about comparing terms of their current accounts with other industry offerings to ensure they are taking advantage of plans with minimal fees and the best investment performance.

Indexed Target Date Funds Challenged in 401(k) Litigation for Too Low Returns

In an interesting twist, the focus of attacks on 401(k) plan fiduciaries has expanded to include challenges to the use of low-cost indexed target date funds. Approximately 10 lawsuits have been filed against plan fiduciaries for using the BlackRock LifePath indexed target date funds. The challenge claims the BlackRock funds have had consistently lower returns than the most-used and best-performing, (mostly) actively managed target date funds. The T. Rowe Price Retirement Funds and Fidelity Freedom Funds were cited as examples, among others.

Different from the all-too-familiar claims in nearly 200 recent lawsuits that challenged 401(k) plan fees, expenses, and sometimes investment performance, these lawsuits challenge only investment performance.

They allege that investment returns were sacrificed in favor of low costs. However, there are two critical differences in the BlackRock funds versus the funds they are being compared with that are likely major contributors to performance differences.

- To-retirement versus through-retirement. A key element of target date fund design and construction is whether the gradual shift along the glidepath from more equities and fewer bonds to fewer equities and more bonds stops at a target retirement age (65, for example) or continues past it. Target date funds that stop the glidepath shift upon reaching the target retirement age are referred to as to-retirement strategies, while those that continue to grow more conservative after a target retirement age is reached are called through-retirement strategies. It can be expected that to-retirement strategies will generally have lower equity exposure than their through-retirement counterparts. This can lead to higher long-term returns for through-retirement funds than for to-retirement funds in certain market cycles. The BlackRock LifePath funds are to-retirement strategies, but they are being compared to through-retirement strategies.

- Active versus passive. The BlackRock LifePath funds are made up of passively managed underlying funds, while most of the higher-returning comparison funds are constructed with actively managed underlying funds. Passively managed investments are designed to match their target indexes, while actively managed funds are designed to outperform their benchmark indexes. The comparison funds are all funds that have successfully outperformed their benchmark indexes.

There are legitimate and prudent reasons for plan fiduciaries to select target date funds with either a to-retirement or a through-retirement strategy, and with either actively managed or passively managed underlying fund components. It’s also paramount that plan fiduciaries understand they have no responsibility, per ERISA, to select the best-performing investment options or the cheapest. However, in a familiar refrain from prior Fiduciary Updates, it is essential that those choices be made through a thoughtful evaluation and selection process. It is equally important that those decisions be well documented.

UnitedHealth Group CFO Added as an Individual Defendant in Lawsuit Challenging the Retention of Underperforming Target Date Funds

UnitedHealth Group (UnitedHealth) is the subject of another lawsuit challenging fiduciaries’ use of target date funds. The complaint, filed in 2021, alleges that the company’s retirement plan continued to offer Wells Fargo target date funds from 2015 to 2021, even though they consistently and significantly underperformed. Snyder v. UnitedHealth Group (D. Minn. 2021).

Through the litigation discovery process, the plaintiffs claim to have found evidence that although the UnitedHealth fiduciary committee had determined to remove the Wells Fargo funds, the CFO interceded to keep those funds in place. An amended complaint was filed in August 2022, adding the CFO as an individually named defendant. The amended complaint alleges that the CFO directed a comparison of UnitedHealth’s business relationships with Wells Fargo and the firms whose funds were candidates to replace Wells Fargo. Upon determining that Wells Fargo was a significant business partner, the decision was made to retain the Wells Fargo funds. Soon after, the plan’s fiduciary committee was restructured to include the CFO, who had not previously been a member. The complaint contends that UnitedHealth’s business success took precedence over the interests of plan participants, thereby violating ERISA’s exclusive benefit rule and causing losses for plan participants.

So far, only the plaintiff’s allegations are known. Counsel for the defendants issued a statement noting that lawyers may choose to pursue baseless claims and stating that allegations against the CFO are completely without merit.

This case and the multiple lawsuits challenging the BlackRock LifePath funds (reviewed earlier in this Fiduciary Update) underscore the importance of carefully selecting and monitoring target date funds—along with a plan’s other investments.

Recent Decision in CommonSpirit Supports Fee Case Dismissals by Two Other Circuit Courts of Appeal

Last quarter, we reported on a decision from the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals affirming the dismissal of a 401(k) plan fees case in CommonSpirit. Relying on the reasoning in that case, dismissals have also been upheld in the Seventh and Eighth Circuits. These cases and other recent dismissals at the district court level are a departure from a recent trend of allowing these cases to proceed. This may indicate that courts are developing a more complete understanding of this area.

In Albert v. Oshkosh Corp. (7th Cir. 2022), now-familiar claims were filed, alleging too-high fees among other complaints. Affirming dismissal, the court said the following:

- Regarding an allegation that recordkeeping fees were too high: “We previously rejected the notion that a failure to regularly solicit quotes or competitive bids from services providers breaches the duty of prudence.”

CAPTRUST comment: Even though this statement provides some breathing room for fiduciaries, it is a fiduciary duty to pay only reasonable fees for plan services. We believe it is a best practice to periodically benchmark fees against similar plans and services.

- Regarding the use of the least expensive share classes—that is, net of revenue sharing that is allocated back to participants’ accounts that use the revenue-share-producing investments—the court rejected this argument, saying, “This is a novel theory.”

CAPTRUST comment: While this particular court may view this as a novel approach, a significant number of plans utilize it, and one recently filed fees case directly alleges a fiduciary breach in not using it. There is no one right way to pay for plan fees, but a full understanding of all plan fees is required.

- Regarding mutual fund investment expenses, “The fact that actively managed funds charged higher fees than passively managed (index) funds is ordinarily not enough to state a claim.”

In Matousek v. MidAmerica Energy Company (8th Cir. 2022), again, familiar claims were made. Affirming dismissal, the court said the following:

- Regarding an allegation that recordkeeping fees were too high: “After all, we have been clear that the key to stating a plausible excessive-fee claim is to make a like-for-like comparison.” The court rejected the use of general industry benchmarks that did not demonstrate an apples-to-apples comparison.

CAPTRUST comment: Periodic like-to-like benchmarking is a best practice.

- Regarding a claim that underperforming funds were retained, the court determined that the complaint was not sufficient because it did not include a meaningful comparison to demonstrate that the currently used funds actually underperformed. However, “in one earlier case a combination of a market index and other shares of the same fund did the trick, but there is no one-size-fits-all approach.”

CAPTRUST comment: It is a best practice to periodically review and evaluate plan investments relative to appropriate benchmark and peer group data—and document those reviews.

Two District Courts Conclude Plan-Related Data is Not a Plan Asset

A wide-ranging lawsuit was brought against Automatic Data Processing, Inc, making the usual allegations of overpaying fees and retaining underperforming investments. This suit also included the claim that plan data is a plan asset and that plan fiduciaries breached their responsibility by allowing the plan recordkeeper, Voya, to use participant data to solicit plan rollovers and sell other products. The court decided that plan data is not a plan asset and dismissed that claim. The court did note that it is possible that plan fiduciaries should have limited Voya’s use of plan data, but nothing in the complaint supported a finding that failure to do so caused losses or harm. Berkelhammer v. Automatic Data Processing Inc. (D. N.J. 2022).

In the second case, TIAA-CREF was challenged for using plan data to encourage plan rollovers and sell other services. The judge stated in his opinion that due to TIAA’s lagging market share in the retirement plan space it took action to support its business and implemented a multi-step approach. This strategy included offering free financial planning services to plan participants so the company could decide whom to target for other services. The company also implemented processes to encourage internal advisors to sell other services. The court concluded that plan data was not a plan asset that could give rise to TIAA being a fiduciary or committing a fiduciary breach for the data’s misuse. Carfora v. Teachers Insurance Annuity Association of America (S.D. N.Y. 2022).

Although these cases do not find a fiduciary responsibility for the use of plan assets, plan fiduciaries will likely want to be aware of any cross-selling and ancillary services provided to their employee/participants by plan recordkeepers. Also, this is a developing area and not all courts will necessarily reach a similar conclusion, depending on the facts and circumstances.

Independent Fiduciary Provides Shield to Plan Fiduciaries in Employer Stock Case

Boeing’s 401(k) plan permits plan participants to invest in Boeing stock. For more than 15 years, the Boeing Investment Committee has retained an independent fiduciary who has both independent and exclusive responsibility for monitoring Boeing stock as a plan investment. After two fatal crashes of Boeing’s 737 MAX aircraft, the company’s stock lost considerable value. In the wake of the second crash, plan participants sued Boeing and its fiduciary committees, alleging that—after the first crash and the subsequent recovery of the flight data recorder—Boeing knew and concealed the risks of the 737 MAX aircraft. They argued that Boeing stock should have been eliminated from the plan. A lawsuit was not brought against the independent fiduciary.

The court evaluated the respective roles of Boeing, its fiduciary committees, and the independent fiduciary. It concluded that with the appointment and delegation of exclusive responsibility for the Boeing stock to the independent fiduciary, neither Boeing nor its committees had a fiduciary role or responsibility with respect to the Boeing stock. As a result, the case was dismissed. Dismissal was appealed to the Seventh Circuit, which affirmed dismissal. Burke v. Boeing Co. (7th Cir. 2022).

This case illustrates a potential benefit of retaining an independent fiduciary in employer stock situations that may warrant it.