-

Solutions

- Solutions

-

Individuals & Families

- Individuals & Families

- Individual Investors

- Executives & Business Owners

- Families with Complex Needs

- Professional Athletes

-

Retirement Plan Sponsors

- Retirement Plan Sponsors

- Corporations

- Educational Institutions

- Healthcare Organizations

- Nonprofits

- Government Entities

- Endowment & Foundation Leaders

- See All Solutions

Comprehensive wealth planning and investment advice, tailored to your unique needs and goals.Investment advisory and co-fiduciary services that help you deliver more effective total retirement solutions.CAPTRUST provides investment, fiduciary, and risk management services for nonprofit organizations. -

About Us

- About Us

- Our People

- Our Story

- Learn About CAPTRUST

-

Locations

-

Resources

- Resources

- Articles

- Podcasts

- Videos

- Webinars

- See All Resources

Non-Liquid Diversification Strategies

- Private Real Assets: Investing in private real assets, such as real estate, expands your portfolio beyond your business. Real assets can offer steady income, potential tax advantages, a hedge against market volatility, and capital appreciation. A well-rounded real estate strategy should balance core, value-add, and opportunistic investments to align with your goals.

- Private Debt: Private debt offers a wide range of opportunities, including direct and enhanced lending. Direct lending means loans primarily to private-equity-backed companies, often featuring floating rates, rate floors, covenants, and first lien or unitranche structures. Enhanced lending refers to less correlated strategies, typically backed by non-corporate assets, such as asset-based lending, royalty streams, structured credit, infrastructure debt, real estate debt, and venture debt. Choosing the right mix of these options can help ensure alignment with your portfolio’s objectives.

- Private Equity: Private equity investments should reflect your risk tolerance and goals. Three options for private equity investments include buyout opportunities, venture or growth opportunities, and opportunistic strategies, which include diversification through secondaries, distressed-for-control deals, sports investing, or GP stakes.

Liquidity Events

Events such as IPOs, mergers, or acquisitions offer opportunities to liquidate holdings and diversify. Conducting thorough due diligence and scenario modeling can show how each option may impact your long-term financial plan.

Enhancing Diversification Through Tax and Charitable Strategies

Managing the tax impact of diversification is critical. Coordinating with all professional advisors will help ensure tax efficiencies are fully identified and captured. Potential strategies include:

- Spreading the sale of private shares over several years;

- Using tax-advantaged accounts; and

- Leveraging private placement life insurance.

Another option for diversification is to donate private company shares to a charitable trust or foundation. This can diversify holdings while providing tax benefits and supporting causes that are important to you.

Structures such as donor-advised funds, charitable remainder trusts, and charitable lead trusts may be appropriate. We recommend working closely with advisors who specialize in charitable planning to select the right approach.

Five Key Tenets of a Private Investment Program

- Vintage-Year Diversification: Committing a set amount annually helps mitigate risks tied to any one investment cycle.

- Strategy Diversification: Complementary strategies enhance risk-adjusted returns. Flexibility is key to capitalizing on opportunities.

- Robust Manager Due Diligence: Thorough investment, organizational, and operational due diligence is critical due to the illiquidity of private assets.

- Global Asset Allocation: Incorporate your business, real estate, and alternative investments into a unified global portfolio view.

- Long-Term Focus: Building a mature private investment program typically takes five to seven years. Patience is essential.

Remember, diversification isn’t just a financial tactic—it’s a foundation for wealth preservation and growth. By spreading investments across different asset classes, industries, and geographies, private company owners can reduce risk and unlock opportunities for long-term prosperity.

In today’s evolving markets, diversification is a powerful strategy to protect and grow your wealth, ensuring your legacy endures for generations.

Partnering with a trusted financial advisor can help tailor these strategies to your unique financial circumstances.

The information provided is for educational purposes only and does not constitute an offer, solicitation, or recommendation to sell, or an offer to buy, securities, investment products, or investment advisory services. Nothing contained herein constitutes financial, legal, tax, or other advice. Consult your tax and legal professional for details on your situation. Investing involves risk, including the risk of loss. Investment advisory services are offered by CapFinancial Partners, LLC (“CAPTRUST” or “CAPTRUST Financial Advisors”), an investment advisor registered with the SEC under The Investment Advisers Act of 1940.

A: Generally, it’s better to consolidate investments into fewer accounts and, ideally, with one advisor or investment manager.

There is a common misconception in financial management that diversification means having several investment accounts at different institutions or with multiple financial advisors. In truth, diversification refers to the variety of investments in your portfolio, not where you hold them. For instance, maintaining multiple 401(k)s with different providers is not diversification, but balancing the quantity of stocks and bonds within your 401(k) is.

Asset consolidation has four main benefits:

- Optimized planning. With investments in one place, it’s easier to see your full financial picture. This helps you make better financial planning decisions.

- User-friendly implementation. Consolidation also makes it easier to implement portfolio changes like buying and selling investments. It can also reduce account administration fees.

- Simplified recordkeeping. Working with fewer institutions means fewer monthly statements and tax documents.

- Reduced fees. Generally, the more assets you hold with one provider, the more opportunities you may have for reducing or eliminating account fees, transaction costs, and other expenses.

For cash accounts, different rules apply, and it can sometimes be a good idea to spread deposits across multiple banks to keep each account balance below $250,000. This is the maximum amount insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC).

Before you make any moves, talk to a financial professional to discuss the best strategy. Asset consolidation will look different for each investor.

AI stocks are garnering a lot of attention lately, and for good reason. In late 2022, the technology sector saw a breakthrough in large language models, allowing AI to learn and respond in conversational language. And in 2023, when Nvidia, which makes processors that power AI technology, delivered second-quarter sales drastically higher than expected, it unleashed a fervor of excitement. In the days after, mega-cap technology stocks rose sharply, pulling the entire S&P 500 Index upward. Since then, AI-related company stocks have seen huge gains, and some huge dips as well.

Although mass adoption is distant, AI has the potential to unlock productivity in a host of different industries, and companies across sectors are now investing heavily in related infrastructure. This means AI also has huge potential to generate wealth.

Despite this potential, it is important to remember that AI is still nascent technology, and investing will be risky. AI stocks are likely to be volatile, it will be difficult to predict winners and losers, and investors could lose everything.

That’s why it’s critical to do your due diligence. Make sure you or someone with AI-specific knowledge is vetting the opportunity set on your behalf, and never invest more than you can afford to lose.

If you do decide to invest in AI, consider a diversified approach: either a portfolio of AI stocks, a mutual fund, or an exchange-traded fund (ETF). These can offer better diversification than individual stocks alone.

As with any investment, risks abound, and AI strategies will not be right for everyone. A financial advisor can help you understand how AI investments may fit into the larger context of your investment portfolio and how much risk might be appropriate.

Supreme Court Opens Doors to More Litigation—Increased Defense Costs and More Settlements Likely

The Supreme Court has issued a decision that will make virtually all retirement plan fiduciaries subject to being sued for committing a prohibited transaction (PT). The Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) provides a host of prohibited transaction exemptions (PTEs) that permit plan fiduciaries who have acted properly to avoid liability. However, to avoid liability, litigation must get underway and plan fiduciaries must establish that an exemption applies. There will be no quick resolutions of these cases with motions to dismiss. Cunningham v. Cornell University (S. Ct. 4.17.25).

The course that any litigation may take—and what may be exposed—is unpredictable. The Cornell decision makes it more important than ever that plan fiduciaries have and follow a thorough governance and documentation process.

ERISA’s definition of a PT is sweeping, including most business transactions that retirement plans engage in as part of their necessary operations. This includes services as basic and essential as 401(k) plan recordkeeping. An extensive list of PTEs permits these necessary services. The issue in Cornell was whether a PT claim must initially allege that no exemptions apply or, alternatively, whether fiduciaries are required to prove that an exemption does apply. Under this decision, once a PT claim is made, the burden is on plan fiduciaries to prove that an exemption applies.

For context, a PT is any transaction between a plan and a party in interest. Parties in interest include those that would likely have a conflict of interest if hired by a plan, such as plan fiduciaries and their family members. The idea is that agreements with retirement plans should be arm’s-length situations and not insider deals. The party-in-interest definition also includes all plan “service providers.” The current consensus among commentators appears to be that paying a plan service provider with plan assets is a PT.

The Supreme Court did not consider the fair-dealing purposes of the law. Rather, its unanimous decision focused on the structure of how the law is written. ERISA first establishes the broad rule against PTs, and then, in a separate section, creates exceptions to the rule.

Applying rules for interpreting laws, the Court reasoned that by being in a separate section of the law, PT exceptions are “affirmative defenses” and must be raised and proved by the plan fiduciaries accused of a PT. The opinion noted that the Court must “read the law the way Congress wrote it.”

Placing the responsibility for raising PT exemptions on fiduciaries dramatically lowers the bar for plaintiffs to make PT claims that will survive motions to dismiss. A concurring opinion in Cornell observes that all a plaintiff must do to file a complaint that will survive a motion to dismiss is allege that the plan fiduciaries did something that, “as a practical matter, [they] are bound to do.” It went on to observe, “In modern civil litigation, getting by a motion to dismiss is often the whole ball game because of the cost of [litigation].”

The Court acknowledged the likely surge of litigation that will flow from its decision and provided coaching to lower courts on judicial management processes that may help to short-circuit meritless claims.

Supreme Court Seeks Executive Branch Input on Who Must Prove Loss Causation in Fiduciary Breach Cases

In Pizarro v. Home Depot, Inc. (11th Cir. 2024), the court of appeals decided that, in fiduciary breach suits, the plaintiffs must prove there was a loss and that the loss was caused by the offending plan fiduciaries. The Home Depot plan fiduciaries allegedly paid excessive fees for investment advice to plan participants and retained underperforming funds. However, the plaintiffs failed to show that the alleged fiduciary breaches caused a financial loss, and the case was decided in favor of the plan’s fiduciaries. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit affirmed. The 10th Circuit has taken the same position: that plaintiffs are responsible for proving a loss. Other appellate courts—the 1st, 4th, 5th, and 8th Circuits—have held that fiduciaries must prove their actions did not cause a loss.

The disappointed plaintiffs in the Home Depot case have asked the Supreme Court to accept an appeal of the 11th Circuit’s decision and resolve the conflicting decisions on the issue among the circuit courts. Pizarro v. Home Depot, Inc. (S. Ct., Pet. for Cert. filed 12.3.24).

Unlike other appellate courts, the U.S. Supreme Court generally decides which cases it will hear. The Court has not decided whether it will accept the appeal. However, indicating its interest in the case, it has asked the solicitor general to “express the views of the United States” on the issue. In the Home Depot circuit court appeal, the Department of Labor (DOL), under the Biden Administration, supported requiring fiduciaries to prove that their actions did not cause a loss.

Executive Action: No Retirement Plan Investments Allowed in “Foreign Adversary Companies”

On February 21, 2025, President Trump issued a presidential action titled “America First Investment Policy.” It is quite broad. With respect to retirement plans, it says, “To protect the savings of United States investors and channel them into American growth and prosperity, my Administration will […] restore the highest fiduciary standard required by the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974, seeking to ensure that foreign adversary companies are ineligible for pension contributions.”

It then directs the Secretary of Labor to “publish updated fiduciary standards under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 for the investment in public market securities of foreign adversary companies.”

The following are identified as “foreign adversaries.”

- The People’s Republic of China, including the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region and the Macau Special Administrative Region

- The Republic of Cuba

- The Islamic Republic of Iran

- The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea

- The Russian Federation

- The Regime of Venezuelan Politician Nicholás Maduro

A definition is not provided for “foreign adversary companies.”

Also, there is no deadline for action by the secretary of labor. Legislation intended to prevent ERISA-covered retirement plans from investing in foreign adversary companies has been introduced in both the House of Representatives and the Senate. We will continue to monitor developments.

DOL Adopts New Process for Self-Correction of Late Contributions

One of the most frequent errors among retirement plans is the late deposit of participant 401(k) contributions. Generally, 401(k) contributions must be deposited with the recordkeeper no later than income tax withholding is due to be deposited with the federal government. When a late deposit happens, the deposit must be made (with lost earnings) and the appropriate excise taxes paid along with an IRS Form 5330 filing.

In the event of a late deposit, plan sponsors may, but are not required to, file with the DOL under the Voluntary Fiduciary Correction Program (VFCP). If accepted, the DOL will issue a no-action letter.

The DOL has recently expanded the VFCP to include a streamlined process for correcting late employer deposits of participant deferrals and some participant loan failures. It is called the Self-Correction Component (SCC). Through this process, documentation of the error is submitted to the DOL online. Then, rather than sending a no-action letter, the DOL sends only an email acknowledging the submission.

To participate in the SCC program, plan sponsors must meet specific recordkeeping requirements. SCC is available only if the amount of lost earnings is less than $1,000 and if late payments and earnings are corrected within 180 days of when salary deferrals were withheld from participants’ compensation.

Jury Awards $38.8 Million for Overpayment of Recordkeeping Fees

In a rare jury trial on an ERISA issue, a New York jury has decided that fiduciaries in the Pentegra multiple employer plan (MEP) paid excessive administrative fees. A verdict of $38.8 million was handed down. Khan v. Bd. of Dirs. of Pentegra Defined Contribution Plan (S.D. N.Y., Jury Verdict 4.23.25). Breaking with most other courts, a few federal courts in the 2nd Circuit (New York, Connecticut, and Vermont) have permitted jury trials.

The Board of Directors of Pentegra Defined Contribution Plan (Board of Directors) is the plan sponsor of an MEP that has been adopted by approximately 250 banks, has approximately $2 billion in assets, and includes approximately 25,000 participants. The Board of Directors retained Pentegra Services Inc. (PSI) to be the plan’s administrator.

PSI took on extremely broad responsibilities, including monitoring its own fees. PSI was selected to serve the Pentegra plan without a competitive bid process or negotiations, and its contract has been renewed without any fee benchmarking since it was retained in 2007. The president and CEO of PSI is a member of the Board of Directors.

The above facts are drawn from a court decision on a motion filed in the case. The basis for the jury’s decision is not known. However, the facts of the case likely gave the plaintiff’s lawyers plenty of scenarios to weave in their presentation to the jury.

Plan Fiduciaries Win Challenges to Retaining Underperforming Investments

This quarter, a number of suits alleging that plan fiduciaries breached their duty of prudence by retaining underperforming investments have been resolved in the fiduciaries’ favor. The following are highlights.

- Enstrom v. SAS Institute. (E.D. N.C. 2025): SAS Institute was challenged for retaining underperforming investments. Deciding for the plan’s fiduciaries, the judge noted:

- The appropriate inquiry focuses on the process that the fiduciary used to make the challenged decision, not the results of the decision.

- Fiduciary duties require prudence, not prescience.

- A plaintiff must plausibly allege that a prudent fiduciary in like circumstance would have acted differently.

- Plaintiffs use a suite of exotic performance metrics to make their point. Even under ERISA, plaintiffs must plead facts that are sufficient to state a claim that is plausible on its face.

- The challenged funds generally provided returns within 1 to 2 percentage points of the plaintiff’s handpicked comparator. Alleged underperformance of between 1 and 4 percent of a benchmark fails to state a plausible ERISA claim.

- Cutrone v. AllState Corp. (N.D. Ill. 2025): AllState was challenged for retaining Northern Trust’s underperforming target-date funds. Deciding for the plan’s fiduciaries, the judge noted:

- The plaintiffs did not provide useful benchmarks against which to judge the allegedly underperforming funds.

- The fund’s own custom benchmark was close to an apples-to-apples comparison and showed a performance variance of only +/- 0.20 percent.

- The plan’s independent investment consultants “consistently blessed” the funds as being suitable for inclusion in the plan.

- Johnson v. Russell Investments Trust Company (S.D. Fla. 2025): Russell and Royal Caribbean Cruises were sued for retaining Russell Investments target-date funds. Deciding for the plan’s fiduciaries, the judge noted:

- Underperformance in a five-year snapshot of a fund that is supposed to grow for 50 years does not show that the fund is objectively imprudent.

- After finding that the Russell funds were not objectively imprudent, the judge rejected challenges to the investment review process, saying, “A fiduciary who relies on prayer, astrology, or just blind luck will be shielded from liability if the beneficiary cannot show that the resulting investment is imprudent.”

- Partida v. Schenker, Inc. (N.D. Cal. 2025):Schenker was sued for retaining the underperforming Wells Fargo Growth Fund. Deciding for the plan’s fiduciaries, the judge noted:

- There is nothing presumptively imprudent about a retirement plan retaining investments through periods of underperformance as part of a long-term strategy.

- A passively managed (index) fund is an inappropriate benchmark against which to evaluate actively managed funds.

- There may be good reasons to use high-cost share classes. Higher-cost share classes may offer revenue sharing that benefits the plan.

What Happened

On April 17, 2025, in a unanimous opinion, the Supreme Court found that, in order to bring a prohibited transaction claim under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA), plaintiffs need only to allege a prohibited transaction occurred.

Why It Matters

Some are concerned this framework could allow plaintiffs to easily move past the motion-to-dismiss stage, which could create costly and time-intensive discovery processes for defendants.

- The Court acknowledged these concerns and was sympathetic to the argument that its ruling could increase litigation.

Weeding Out Meritless Claims

In its decision, the Court highlighted specific tools that district courts could use to dismiss and discourage meritless claims.

- The tools identified are not commonly used today, so it will be interesting to see how the litigation space evolves based on the Court’s recommendations.

What’s Next for Plan Sponsors

If defendants believe the prohibited transaction claimed by a plaintiff falls within one of the stated exemptions, they must show that an exemption applies.

- Going forward, when a PT claim is brought against an ERISA plan’s fiduciaries, those fiduciaries will have to show that a prohibited transaction did not occur, or affirmatively plead that the PT was covered under a prohibited transaction exemption (PTE).

For more information, please contact your CAPTRUST Financial Advisor.

Key Takeaways

• In a rule-shifting world, confidence and clarity come from diversification and sound planning.

• The first quarter marked a turning point, as markets that were priced for perfection met maximum policy disruption.

• Aggressive and unexpected trade policy shifts caught businesses, world leaders, and investors off guard. Market reaction was swift and severe.

What Happened

Over the first months of 2025, the investment landscape radically transformed. A few short months ago, markets were thriving, fueled by confidence in a stable economy, a strong outlook for corporate earnings growth, excitement for an artificial-intelligence-fueled productivity boom, and optimism around pro-growth policies from the new administration.

Today, investors find themselves grappling with the implications of the most significant reshuffling of global trade policy in a century. The networks of global commerce that have contributed to economic growth and prosperity, both here and abroad, have been upended by the Trump administration’s desire to radically rewrite the rules of trade.

The result could be one of the most important economic shifts of our lifetimes—or a short-lived negotiating tactic from a consummate dealmaker—and one that could change with a single social media post.

Either way, markets reacted powerfully as world leaders, business executives, and investors assessed implications for the global economy. U.S. stocks approached bear-market territory from their mid-February highs. Bond investments initially provided stability amid the chaos, before also succumbing to uncertainty. Gold rallied as a safe-haven asset amid the storm.

In such times, it’s important for investors to think clearly, assess the knowns and unknowns, and evaluate the impact to their financial objectives. How did we arrive at this position? What is the range of potential future outcomes? And most importantly, what steps should investors consider next?

How We Got Here

At year-end 2024, investors celebrated their second consecutive year of 25 percent returns for the S&P 500 Index—a rare occurrence in market history. From its low of March 2020, the S&P 500 had risen by 183 percent, with technology stocks surging more than 288 percent. International equities returned 93 percent during the same period, while bonds remained largely flat due to rising interest rates.

This divergence in returns was partly driven by the U.S. government’s fiscal decisions during and after the pandemic. The degree of COVID-19-era stimulus far surpassed that of other nations, fueling consumer spending and corporate profits, while also contributing to inflationary pressures, leading to higher interest rates.

Although optimism persisted as we entered 2025, we also began to see a shift in the familiar return patterns of the past few years. U.S. stocks showed a modest decline as economic indicators began to soften. Previously high-flying technology stocks showed weakness as investors began to worry that the artificial intelligence frenzy had maybe gotten ahead of itself. Meanwhile, international stocks outperformed, fueled by lower valuations and stimulus pledges to offset the tariff threat. Bonds benefitted from falling interest rates driven by rate-cut hopes.

Overall, the first quarter offered a great illustration of the benefits of global, multi-asset-class diversification.

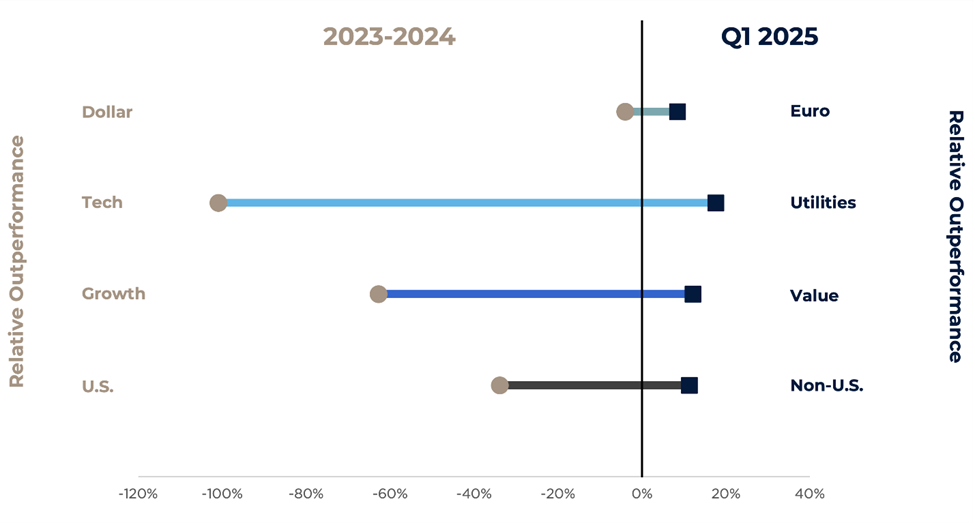

Figure One demonstrates the reversal of recent trends in the first quarter of 2025. In 2023 and 2024, the dollar, the tech sector, growth stocks, and U.S. equity markets showed relative outperformance. Today, however, we see relative outperformance from the euro, utilities, value stocks, and non-U.S. equity markets. Relative performance is a way to compare how two investments performed relative to one another over a specified period. It’s the difference in their returns over the period, and basically answers the question: Which one did better, and by how much?

Figure One: Reversal of Trends, First Quarter 2025

Sources: Federal Reserve Board, Morningstar Direct, CAPTRUST research. Sector returns reflect S&P 500 sector indexes. Growth and value returns reflect Russell 1000 Growth and Value indexes. U.S. and non-U.S. returns reflect S&P 500 and MSCI EAFE indexes.

Trade Takes Center Stage

This landscape shifted radically in late March and early April as the Trump administration moved on its trade agenda. What began as the sequential rollout of targeted policy grew to a crescendo on April 2, when the administration launched a sweeping import-tax program including a universal 10-percent tariff plus reciprocal levies calculated on each nation’s degree of trade imbalance.

If fully implemented, the announced tariff program would have raised approximately $600 billion in revenue—effectively, the largest tax hike in modern U.S. history— while ripping up the script of global commerce.

Market reaction was swift and severe. The S&P 500 suffered a series of days of 4 percent or greater losses, for a total drop of nearly 19 percent from its mid-February high. Global equity markets lost more than $5 trillion of market capitalization in a matter of days.

Meanwhile, the U.S. dollar weakened. Typically, in periods of market stress, investors flock to safe-haven, U.S. dollar-denominated assets, driving the dollar higher. This time, however, because the uncertainty was U.S. policy-driven, investors sought alternative havens, including gold and other major currencies, such as the euro and yen. This unexpected dollar weakness amplified the outperformance of non-U.S. stocks.

Treasury yields fell, suggesting investors were more worried about slower growth than rising prices. On April 4, the 10-year Treasury yield dipped below 4 percent before abruptly rising above 4.5 percent on an intra-day basis on April 9: a worrisome sign of market stress.

More than any other measure, spiking Treasury yields suggested that the market’s tolerance for uncertainty had neared its limit. This, along with rising pressure from businesses, led to the announcement of a 90-day pause on reciprocal tariffs, a move that sent stocks soaring. The S&P 500 rose by 9.5 percent—one of the largest single-day moves in the past 20 years.

Despite the 90-day pause and subsequent temporary exemptions, most of the proposed tariffs remain in place, raising the effective U.S. tariff rate from 2 percent to above 20 percent.

Global policymakers reacted swiftly to counteract the effects of U.S. tariffs. Germany launched an aggressive infrastructure and defense spending package to bolster domestic growth. China ramped up monetary and fiscal support. These measures underscore how profoundly the U.S. trade strategy has coursed through international economic policy.

Manufacturing Exceptionalism

The administration’s trade policy is driven by clear goals: enhancing U.S. prosperity, strengthening supply-chain resilience, reshoring manufacturing jobs, securing fairer trade terms, and funding tax cuts. It’s hard to argue with any of these goals.

What has been debated is the unorthodox approach the administration has taken, forcing parties to the negotiating table by applying maximum pressure. We have already begun to see ripple effects in the form of evolving trade relationships and international alliances. Like water, trade will always find ways to flow. When barriers are erected, new channels form.

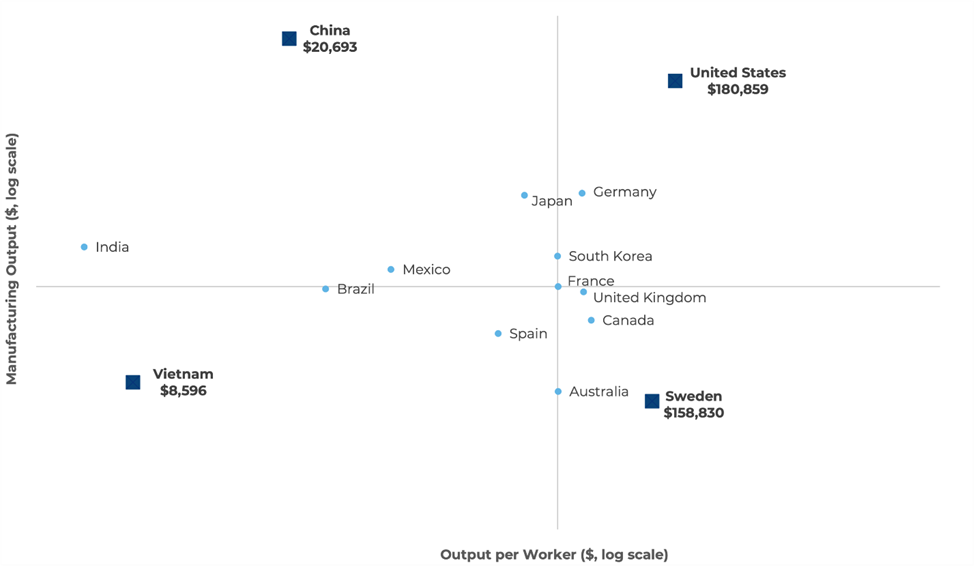

It’s important to recognize that we are starting these negotiations with a U.S. manufacturing sector that is already robust and globally competitive. Despite decades of trade deficits, U.S. manufacturing output approached $3 trillion in 2023, second only to China. As lower-margin production has shifted overseas, the U.S. has retained high-value manufacturing jobs while also becoming more productive.

While China leads the globe in total manufacturing output and employment, the U.S. leads decisively in total output per manufacturing worker. This reflects substantial competitive advantages in productivity, technology, and innovation.

Figure Two: U.S. Manufacturing Leadership, 01.01.2005 through 01.01.2023

Sources: World Bank; International Labour Organization; U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis; Japanese Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry; CAPTRUST research

If the administration’s strategy is successful and manufacturing jobs flood back into the U.S., another practical challenge is finding workers to fill them. Today, there are fewer available workers than job openings. In manufacturing alone, there are an estimated 460,000 job openings: a number expected to grow even before the administration’s recent moves. [1]

Fundamentals Take a Back Seat

With these strategic economic considerations as the backdrop, markets face another challenge: heightened uncertainty driven by opaque and unpredictable policy actions. This type of uncertainty, arising from behind-closed-doors negotiations and rapidly shifting stances, creates an environment particularly disliked by investors—one characterized by ambiguity rather than fundamentals.

This uncertainty is exacerbated by several critical factors.

- Unclear Objectives: The administration’s ultimate goals are ambiguous. Are tariffs intended to level the playing field, boost domestic manufacturing, or raise revenue to fund tax cuts?

- Tariff Trajectory: Almost-daily changes give markets little insight into the policy’s final shape or implementation timeline.

- The Fed’s Tricky Position: The Federal Reserve always faces a delicate balance between managing price pressures and maintaining full employment. Constantly shifting tariff targets make this task Herculean.

Business leaders are beginning to express concern. CEO confidence dropped sharply in April, reaching its lowest level since the pandemic, with two-thirds of survey respondents expressing concern over the potential negative impacts of tariffs. [2] Professional forecasters have also downshifted their economic growth expectations for 2025 while raising their recession odds.[3]

What Should Investors Do?

We clearly remain in a period of elevated uncertainty. There are no historical analogues to help us understand a global trade realignment of this magnitude, and markets are reacting in kind. Such periods of disruption often feel like a time to retreat.

Market volatility, while unsettling, is an important element of investing—not a flaw, but a feature—and precisely why equities offer higher expected returns.

While leading and bleeding headlines intentionally generate fear, and despite today’s volatility, portfolio diversification continues to anchor investor strategy. It is especially important when uncertain policies create the potential for uneven impacts across industries, sectors, asset classes, and regions.

Despite the rocky start, an investor with a balanced portfolio of 60 percent stocks and 40 percent bonds has likely experienced a drawdown in the mid-single digits so far this year. When measured against the degree of volatility and investor angst, losses in diversified portfolios have been relatively contained.

Of course, every investor’s situation is different. Risks, goals, income needs—none of these are one-size-fits-all. This is why we plan. A good plan isn’t knocked off course by periods of volatility; if built well, it can weather storms and help provide clarity in uncertain times. Businesses and markets will adapt. And if investors stay disciplined—diversified, long-term focused, and anchored to a plan—they will, too.

[1] U.S. Manufacturing Could Need as Many as 3.8 Million New Employees by 2033, According to Deloitte and The Manufacturing Institute

[2] Tariffs Push CEO Confidence to Multi-Year Low in April Poll; SBET Report—NFIB

[3] U.S. Economic Outlook Dives Just Three Months into Trump’s Term—WSJ

The information in this article is provided for informational purposes only, and does not constitute an offer, solicitation, or recommendation to sell or an offer to buy securities, investment products, or investment advisory services. Data contained herein from third-party providers is obtained from what are considered reliable sources. However, its accuracy, completeness, or reliability cannot be guaranteed. Nothing contained herein constitutes financial, legal, tax, or other advice. Consult your tax and legal professional for details on your situation. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Investment advisory services offered by CapFinancial Partners, LLC (“CAPTRUST” or “CAPTRUST Financial Advisors”), an investment advisor registered with the SEC under The Investment Advisers Act of 1940.

How Social Security Works

Social Security is funded through payroll taxes, known as the Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA). While working, you contribute a portion of your earnings (7.65 percent) up to the taxable wage base and your employer also contributes (7.65 percent). The taxable wage base is the maximum amount of income subject to Social Security taxes.

There are different benefits that can be accessed through Social Security, the most common of which are retirement benefits, spousal benefits, disability benefits, and survivor benefits.

The amount of benefits you and your family may receive depends on several factors such as your average lifetime earnings, type of Social Security benefit being used, and when you claim at Full Retirement Age. Employers report your wages and tax contributions to the Social Security Administration (SSA). If you’re self-employed, that information is submitted through the IRS via your tax filing.

To get a clearer picture of your personal Social Security outlook, you can create an account at ssa.gov. Through this portal, you can access your Social Security Statement, which includes a record of your past earnings along with estimates for retirement, disability, and survivor benefits. If you’re not enrolled online and are under 60, you’ll receive a mailed statement once you turn 60. The site also offers tools like the Retirement Estimator and other benefit calculators to help you plan more accurately.

Earning Eligibility Through Work Credits

Eligibility for Social Security benefits is determined through a system of credits. You earn these credits by working and paying into the system. Each year, based on your income, you can earn up to four credits. Typically, qualifying for retirement benefits requires 40 credits, equivalent to about 10 years of work. However, for disability or survivor benefits, fewer credits may be sufficient depending on your situation.

Retirement Benefits: Timing and Earnings Matter

Your Social Security retirement benefit is determined by your average indexed monthly earnings (AIME), which is calculated using the average of the highest 35 years of earnings, adjusted for inflation then divided by 720 months. For those born between 1943 and 1954, the full retirement age is 66. That age gradually increases for those born later, capping at 67 for anyone born in 1960 or afterward.

You do have the option to start collecting benefits as early as age 62, but early retirement comes with a trade-off: your monthly benefits will be permanently reduced. On the flip side, if you delay taking benefits past your full retirement age—up to age 70—you’ll earn delayed retirement credits, which increase your monthly benefit by up to eight percent for each year you wait.

Social Security and Disability

If a serious mental or physical health condition prevents you from working for at least 12 months, you may be eligible for disability benefits through Social Security. Keep in mind that the SSA has a strict definition of disability: you must be unable to engage in any substantial work. Temporary or short-term disabilities typically don’t qualify.

Disability benefits don’t start immediately; they begin after a waiting period that includes five full months from the date your disability begins. Because the application and approval process can be time-consuming, it’s recommended to apply as soon as it’s clear your condition will be long-term.

Support for Your Family Members

If you are receiving Social Security retirement or disability benefits, certain members of your family may also be eligible to receive monthly payments based on your earnings record. For example, your spouse—or former spouse—can qualify for benefits at age 62 or older, as long as the marriage lasted at least 10 years (in the case of an ex-spouse). A spouse or former spouse of any age may also qualify if they are caring for your child who is either under the age of 16 or has a disability. Unmarried children under age 18 (or under 19 if still enrolled full-time in high school) may also be eligible. Additionally, children of any age who became severely disabled before turning 22 may qualify for benefits.

Each eligible family member can receive as much as 50 percent of your monthly benefit amount. However, there is a limit to how much Social Security will pay to a family based on the worker’s record. This family maximum typically falls between 150 percent and 180 percent of your full retirement benefit. If the total amount owed to your family exceeds that limit, each family member’s individual payment will be reduced proportionally. Your own benefit, however, will remain unchanged.

Survivor Benefits

Social Security can also provide ongoing support to your family after your death. Survivor benefits may be available to:

- A surviving spouse or ex-spouse age 60 or older (or 50 if disabled)

- A spouse or former spouse caring for your child who is either under 16 or has a disability

- Unmarried children under 18 (or under 19 if still in high school)

- Adult children who were severely disabled before turning 22

- Parents who depended on the deceased financially for at least half of their support

Additionally, your widow(er) or children may receive a one-time lump-sum death payment of $255 shortly after your passing.

How to Apply for Social Security Benefits

When you’re ready to claim your benefits, you have several options: apply online at ssa.gov, call 800.772.1213, or schedule an in-person appointment at your local Social Security office. It’s best to start the process about three months before you want your benefits to begin. However, for disability and survivor benefits, applying as soon as you’re eligible is advisable.

Be prepared to provide documentation such as your birth certificate, W-2 forms, proof of citizenship or lawful immigration status, and your Social Security number. If family members are also applying, similar documents will be required for them. If you don’t have all the necessary papers, an SSA representative can guide you through obtaining certified copies or replacements.

Key Takeaways:

- When markets dip or swell outside normal ranges—reducing or increasing assets in unexpected ways—board members may feel tempted to react and reevaluate the organization’s baseline spending policies. Depending on the circumstances, straying from predefined spending policies may be a good idea for some organizations. What’s key is to understand both the long- and short-term impacts of any potential change, and that can be difficult to do in the moment.

- To better prepare for volatile market behavior, CAPTRUST recommends running stress tests to model different scenarios when establishing spending policies. What will the organization do if a market rally creates a 20 percent asset growth in one year? What will it do if a market pullback reduces asset value by the same amount?

- In these cases, for some organizations, creating conditional spending policies with provisions beyond the core distribution target for each asset pool may make sense.

Click HERE to go directly to a downloadable one-page document about common spending policy types and how to align spending policy with institutional needs.

For those who are involved in making spending policy decisions, here are a few best practices and examples to consider when designing conditional spending policies:

Integrate Conditional Spending Policies into Your IPS, and Review Regularly

A conditional spending policy is designed to encourage an organization to think proactively, not reactively, says Wally Terrell, senior specialist on CAPTRUST’s asset and liability team. “If certain conditions happen in the market, like outsize gains or the recent dip in both stocks and bonds, then spending is adjusted based on pre-planned conversations. This way, board members can be sure they’re not making knee-jerk reactions without considering the long-term perspective.”

Modeling assists decisionmakers in understanding how different events can affect the organization, and how the organization will react. It also helps ensure the team is aware of—and comfortable with—spending policy implications to its portfolio and mission.

It is important to keep in mind that adding conditional spending policies to an investment policy statement (IPS) does not mean the organization will be locked into these provisions. Conditional spending policies simply become another part of the organization’s comprehensive investment strategy, named within the IPS alongside other portfolio parameters and strategic principles, such as the organization’s investment objectives, constraints, and reporting requirements.

As a best practice, the IPS should be reviewed at least annually and any time there is a material change in the organization’s circumstances. As Grant Verhaeghe, institutional portfolios practice leader at CAPTRUST, explains, “When a triggering event occurs, board members can confirm in committee meetings whether the decision made in anticipation of this event is still the one they continue to believe is the right course of action, or not.”

There is nothing suggesting that the organization can’t change course, so long as it follows applicable tax codes, honors donor intent, and aligns with legal compliance in the context of long-term objectives.

Create Overlap Between Spending and Investments

Another best practice is to integrate the organization’s spending and investment policies by creating overlap in the teams that design them. Ideally, the people who are making spending decisions will be some of the same people on the investment committee so that both groups are aware of what is happening in both areas.

“At a minimum, the IPS ought to reference the spending policy, if they are separate documents,” says Verhaeghe. “Organizations might also consider creating a single document that encompasses both policies. Beyond that, it’s even better if an organization can create overlap between the committees that are making these decisions, because overlap creates better information and leads to better financial decisions.”

Terrell agrees: “Allocation decisions should be codified in the organization’s IPS, and everything should revolve around the mission. Spending policy, investment policy, the mission—they should all be in harmony.”

Customize the Plan to Mitigate Your Risks and Meet Your Needs

Although planning itself is a consistent best practice, there is no fixed way to establish a spending policy. Every organization is unique, which means every IPS will be unique, and the conditional spending policies included in that IPS can be infinitely customized. “There is so much flexibility,” says Terrell. “The key is to think about the organization’s unique mission and how its assets support that mission.”

As Verhaeghe explains, “The right spending policies will depend on how the organization utilizes each pool of assets for its ongoing needs.”

In other words, committee members need to understand the organization’s financial vulnerabilities and how different market conditions will impact its mission. For example, some foundations rely heavily on one asset pool, while others depend on grants and donations. The latter will have more flexibility to take investment risks but will also likely see donations decline while markets are down.

Terrell says one widespread practice is to apply different spending policies to each asset pool. For instance, he says, it’s common to have asset pools that function as reserves. Typically, these funds are invested conservatively and may grow slowly over time. In this case, Terrell says, “The foundation may decide to institute a conditional spending policy that says ‘When assets in this pool exceed a certain amount, the organization may institute a simple spending policy. But if assets do not reach the target, there is no spending from this pool whatsoever.’”

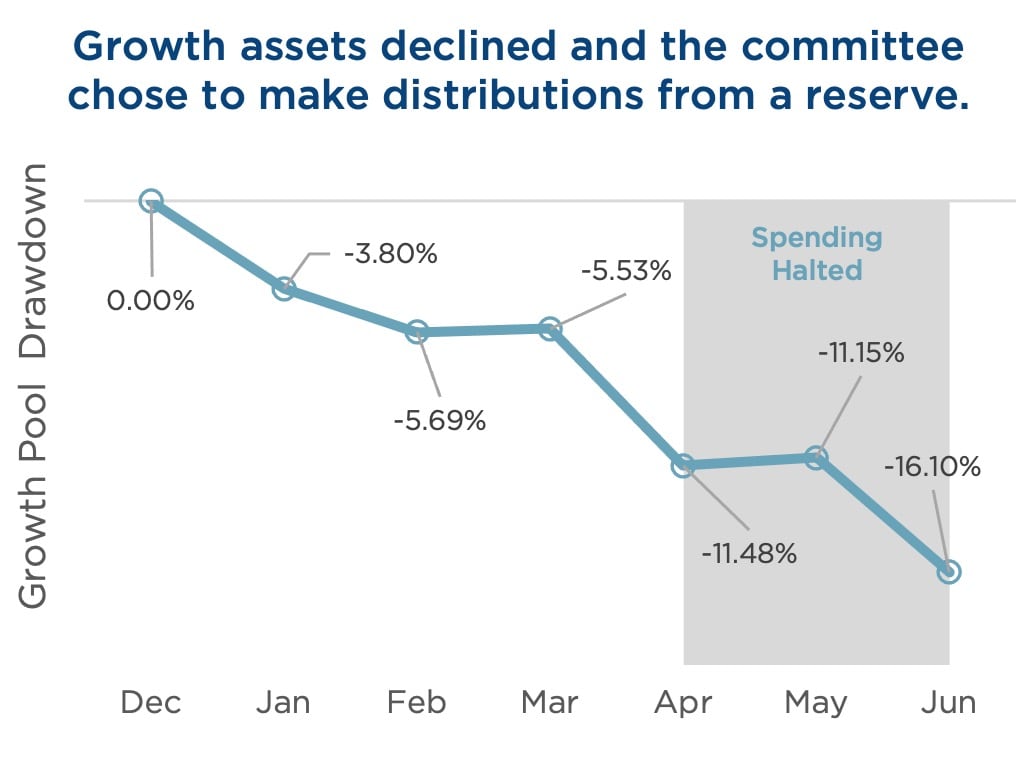

One of the more unusual types of IPS spending policies Terrell has seen is from a client that has, essentially, a growth portfolio and a separate, capital preservation portfolio with a more conservative investment strategy. “Their policy is that if the equity markets decline by more than 10 percent, then instead of distributing from the bigger, growth-focused portfolio, they would instead spend from the more conservative portfolio,” he says. “This way, they don’t unnecessarily deteriorate their equity assets and can use the market downturn as an opportunity to become more tactically aggressive than they otherwise would be under normal spending behaviors.”

Verhaeghe elaborates: “It’s like saying, ‘I don’t want to sell growth assets in a distressed environment.’ Their spending policy means they can hold onto growth assets when market valuation is better.”

As examples of how market conditions may influence mission-centered spending behaviors, Terrell and Verhaeghe offer three case studies for consideration. Note that these examples do not consider regulatory spending requirements that apply to some nonprofits, nor are they meant to serve as ready-made examples for adoption. The right conditional spending policies for each endowment or foundation will depend on that organization’s unique goals and circumstances.

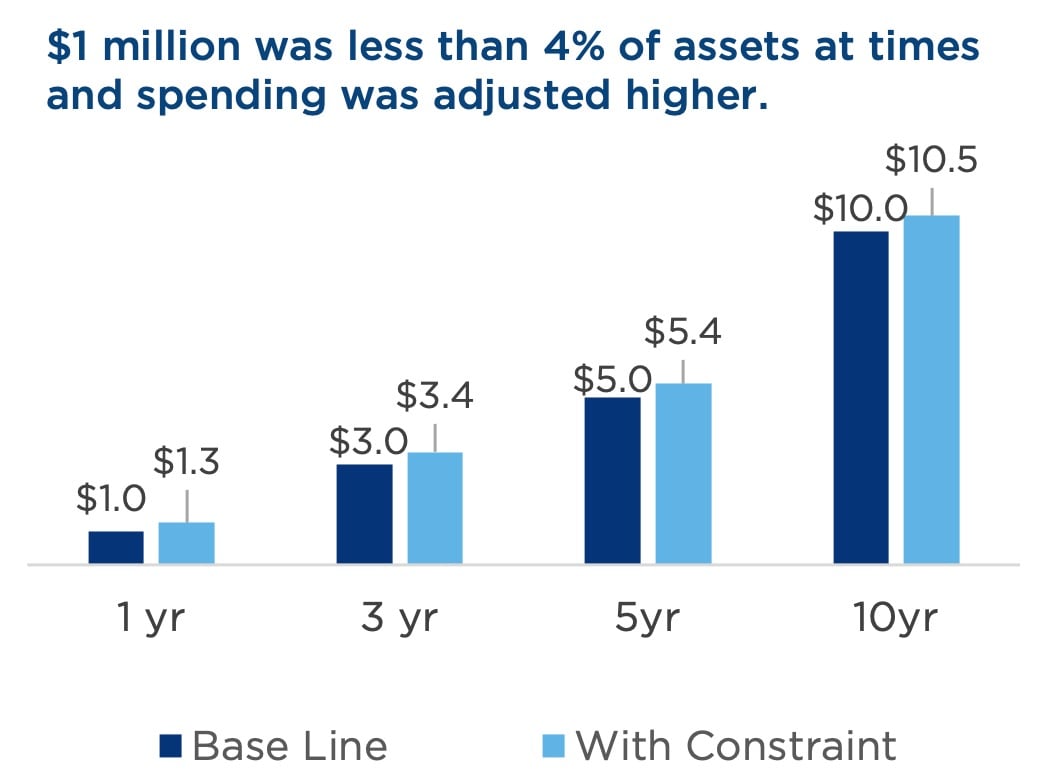

Example A: Spending Floors and Ceilings

An organization may choose a flat dollar spending target, such as $1 million per year, and an additional constraint that restricts the dollar value to a minimum of 4 percent and a maximum of 6 percent of assets. While $1 million is the annual spending goal in this example, if, in a particular year, conditions result in a $1-million spend equaling less than 4 percent of assets, then distributions would be adjusted higher. The inverse would be true for a spending ceiling: If conditions result in $1 million equaling less than 6 percent of assets, then distributions would be adjusted lower.

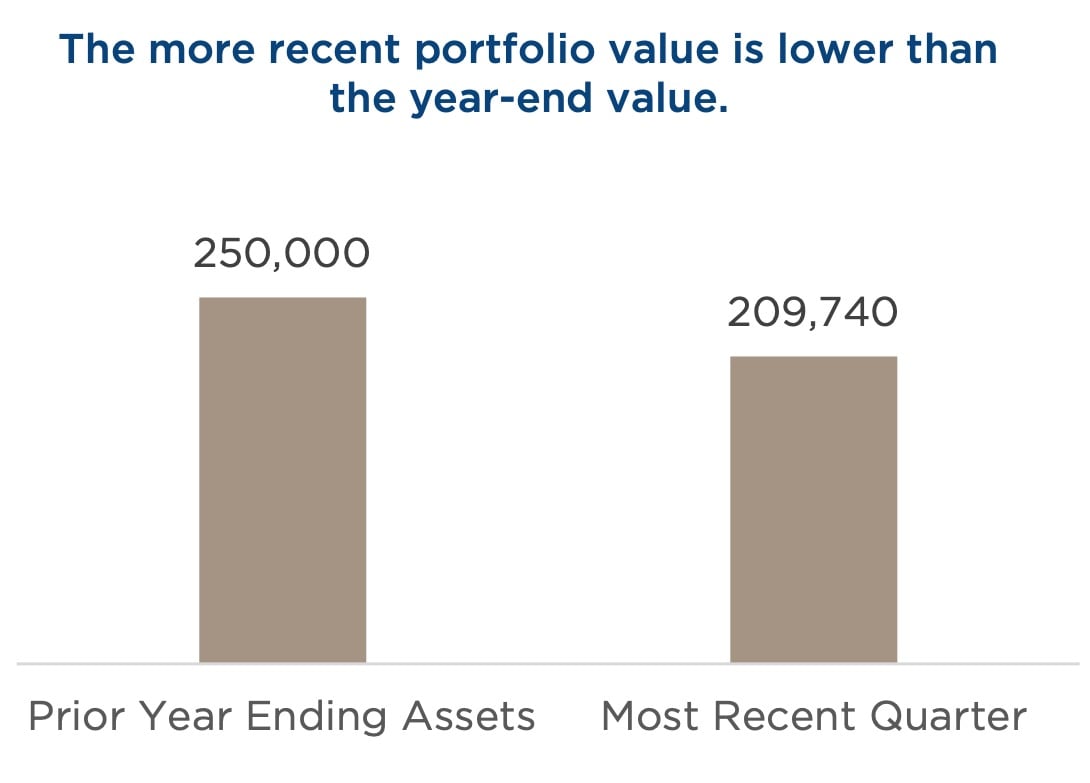

Example B: Portfolio Valuation Date

Another organization may choose a simple 5 percent annual spending policy. Determining the applicable date of market values can impact the sensitivity of spending levels to fast-changing market conditions, Terrell says. For instance, the organization may have targeted spending of $250,000 as of year-end, but the amount would be lowered to $210,000 if an additional rule considers a more recent asset value. The organization may choose to make the inverse true as well, specifying that if asset values on a defined date equal more than $250,000, spending may be raised. This could happen as the result of an unusually large rally or after the receipt of a large gift, for example.

Example C: Market Conditions

Some conditional spending policies may adjust spending levels when market performance meets certain thresholds or when assets rise above—or fall beneath—specific values. Another option is to temporarily halt distributions after a large enough decline in the portfolio, when assets fall below a reserve level. Some organizations will also choose to increase spending over time to address inflation.

When Markets Are Down

“No matter which policies are implemented,” says Verhaeghe, “every organization will have to consider its unique requirements. A private foundation might be subject to IRS rules, while a public foundation might have more flexibility. One organization may rely heavily on an endowment or foundation to cover its operational expenses, and another may have a mission that requires significantly more spending in a tough market.”

This is a common theme. Many endowments and foundations have a greater need for spending when markets are depressed. In fact, for some of these organizations, reducing spending in times of disruption will run contrary to the reason they exist—to support people, institutions, and communities, especially when they need it most.

“It’s not lost on me that telling endowments and foundations to spend less in a difficult economic environment is easy to say and hard to do,” Verhaeghe says. “But this is unlikely to be the only time that markets are volatile or down.”

His advice: “Stay committed to the mission. But also, as a long-term best practice, the more planning an organization can do, the more likely it is that its team will make good financial decisions, because planning helps create balance between immediate spending needs and long-term spending plans.”

Understanding that the organization will almost certainly face another unusual market makes a clear case both for robust planning and for conditional spending policy design. “With a defined spending policy that is formally documented in the organization’s IPS, decision makers are not simply reacting to portfolio growth or decline,” says Verhaeghe. “They’re making proactive decisions that help protect the organization’s ability to achieve its mission, both now and for the long run.”

As you plan for your estate, one important decision you’ll have to make will be your choice of trustee. This is also often one of the most challenging choices.

Your trustee holds legal title to the assets in your trust and has a responsibility to act in the best interests of the trust beneficiaries. They must follow the instructions in the trust document as well as the rules laid out by state and federal laws. Unlike a personal representative or executor who may serve for one to two years, a trustee may serve for a much longer term.

If you have a revocable trust, you will probably serve as trustee during your life, but you will also need to name a successor to take over after you die or if you become incapacitated. Many people wonder if they should choose a family member or close friend, or whether they will be better off with a professional trustee. Each of these options has its advantages and disadvantages.

Choosing Family or Friends as Trustees

A family member or friend may be more likely to understand your wishes and family dynamics. In addition, a family member may charge little or no fee. At the same time, they may lack the skills to carry out this role. If there are disagreements between the trustee and the beneficiaries, family relationships can be strained.

If the trustee is also a beneficiary, then the trust must be carefully drafted to avoid any adverse income or estate tax consequences. Finally, if the trust is intended to last for generations, the trustee will need a successor, or successors, to take over in the event of death or disability.

Choosing a Corporate or Professional Trustee

A corporate or professional trustee will have the expertise to manage the trust and handle the administrative details. In addition, they can deal objectively and unemotionally with the beneficiaries. A corporate trustee will not die, which provides continuity.

One drawback is that a corporate trustee may charge a fee, while a family member may not. Furthermore, the trustee may not know your beneficiaries very well and may act more conservatively than you would have intended. However, this may be less of a factor if you choose a trustee with whom you have a relationship so that they understand your wishes and can carry them out.

Making the Decision

Your decision will depend on a variety of factors. In some cases, especially if the trust is large, grantors will name a family member and a corporate trustee as co-trustees to get the best of both worlds.

It is also important to consider the goals of the trust, along with its size, expected duration, and the types of assets it will hold. For example, a complicated trust that is expected to last for generations may mean that a professional trustee is more suitable. You should also consider whether you have an individual in mind whom you can trust completely, and how they would negotiate family dynamics.

As you make this decision, pay attention to some of the provisions in your trust that relate to your trustees. You may think some of the sections in the back of the trust are unimportant or are standard, boilerplate language, but these sections can have significant consequences. Read them and know what they entail.

You should review who has the power to remove trustees and appoint successors after your death. If you have multiple trustees, the trust should specify how decisions are made when trustees disagree. If you do choose a family member or friend, the trust should give that individual the authority to hire professionals to assist them.

Ultimately, your choice of trustee is a personal decision, and there is no one right answer for everyone. For this reason, it is important that you take the time to make this decision thoughtfully and intentionally. By making your wishes regarding your successor clear, you can help clear the path to a smooth transition for your beneficiaries.

It is common for businesses and nonprofit organizations to have large asset pools, like cash or operating reserves, that aren’t yet designated for a specific goal or need. Often, these asset pools have been set aside as rainy-day funds and have grown over time beyond their necessary size. Properly managed, these pools can swell to be a source of capital growth for an organization, but a surprising number of institutional asset pools (IAPs) remain highly conservative when they could be growing.

Typically, IAPs are managed by either an organization’s internal investment committee or a third-party advisor. In both scenarios, the portfolio manager aims to maximize earning power so that the asset pools are not losing value or simply sitting stagnant without growth.

For example, consider a privately owned business that has recently accumulated quite a bit of cash after two consecutive quarters of strong sales. The owners want to keep the money accessible to the company but are also interested in taking advantage of a current market dip to grow their assets over time. In this case, they may choose to manage the funds themselves, investing in stocks, bonds, and other assets of their own choosing, or assign management to an independent advisor.

Depending on the type of organization and the state in which it operates, each institution may or may not be subject to legal regulations regarding fiduciary responsibilities. But even if the organization falls outside the legal definition of a fiduciary, companies still have an ethical responsibility to their constituents to manage assets prudently, says Grant Verhaeghe, CAPTRUST senior director of institutional portfolios.

“Any person who works as a steward of an organization’s assets should be thinking about and learning best practices for institutional asset pool management,” Verhaeghe says. For institutions that use an internal investment committee for asset management, here are some best practices to consider.

Consider Investment

When considering whether to invest institutional asset pools, there is no one-size-fits-all threshold or standard investment strategy, says Verhaeghe. “Depending on the organization’s unique goals and liquidity needs, each one will use these pools differently and have different objectives,” he says.

Eric Bailey, head of CAPTRUST’s endowment and foundation practice, agrees: “The threshold will be different for every organization, but in general, if you think your organization could be earning a material amount of money through investment, then it’s a good idea to talk about investment strategies so you can put existing IAPs to work.”

For example, Bailey says, imagine a business has something like $10 million sitting on its balance sheet in a variety of places, currently earning zero dollars. Through investment, this business could potentially earn a return on its cash reserves. “Even small amounts can make a material difference to annual profit-and-loss statements,” he says. “The company could then deploy those earnings on a discretionary basis, for instance as bonuses or by hiring more people.”

What’s key is understanding both the upside potential and risks involved in IAP investment so that the organization can make informed decisions with appropriate short- and long-term perspectives.

Account for Time Horizons

Another best practice for IAP management is to consider time horizons for invested assets, or how quickly you might need to deploy the capital. Some asset pools will need to be spent in the next month; others in the next one to three years; and still others can sit in waiting for a longer period. Which asset pools will be good candidates for investment depends on the organization’s cash-flow needs and vulnerabilities.

As Bailey says, “One of the keys to managing IAPs is matching the money to the right time horizon to create the right investment strategy.”

A nonprofit, he says, may need a larger rainy-day fund of liquid assets that are easily accessible and safely stored, just in case donations diminish or the organization doesn’t receive a particular grant they were used to receiving. “These reserves are typically managed conservatively, with capital preservation at center of mind,” says Bailey. “They need to be liquid, safe, and readily available. But asset pools with longer time horizons may be good options for a little more risk, and you may potentially see a higher rate of return.”

Manage Risk

Evaluating how much risk to take with your IAPs depends on how a market decline would affect your organization both now and in the long-term future. Again, each institution will be unique. “The important piece is to fully consider the implications of potential growth or potential loss before you make IAP investment decisions,” says Bailey.

For example, Bailey says, consider a healthcare organization—a hospital that has issued municipal bonds to upgrade its equipment. The bond underwriters give the hospital a credit rating based on its debt, and the hospital will have debt covenants it must meet. “If investments drop too far in value because of a market decline, the hospital can be downgraded by credit rating agencies. This downgrade could cost the organization additional interest expense in future bond issuances or make their bonds less desirable,” he says.

A publicly traded company, on the other hand, will need to consider how investment gains and losses may impact its quarterly earnings statements and, therefore, its stock value.

“Investments on a balance sheet are naturally going to go up and down over time,” Bailey says, “and those changes will flow through to impact other areas of the organization. The critical element is understanding what areas will be impacted and how so that you can make the best possible decisions.”

At times, an investment committee or financial advisor may be managing institutional assets that have liabilities attached. In this case, Verhaeghe recommends organizations create risk models that explain the conditions under which it may be appropriate to take risk, and when it is not. Factors to consider include when the money will be needed, what the expected return will be, and how much risk the organization is able and willing to take.

Document the Process

“Regardless of whether the organization is considered a fiduciary, it’s a good idea to follow a sound process around your investment decisions and document each step,” says Verhaeghe. “That way, if anyone ever asks questions about what you chose or why you chose it, you have the answers.”

These answers may include articulating the organization’s financial needs, goals, and vulnerabilities; documenting practices in an investment policy statement; gathering regular reporting statements; or revisiting goals as the facts and circumstances change over time, Verhaeghe says.

“No two institutions are the same,” says Bailey, “There are dozens of different variables that will impact how each organization should be investing.” For instance, whereas a retirement plan will have a long-term time horizon and specific goal as it relates to each participant or beneficiary, a small, privately owned business may have the goal to maintain purchasing power of its operating reserves and potentially grow that purchasing power over time.

By following these practices, organizations that are independently managing their IAPs can deliver on their fiduciary responsibilities, whether legally mandated or not. However, for organizations that want assistance, managing institutional asset pools is an easy add-on to a trusted relationship with an existing financial advisor. Whichever path these institutions choose, they can be sure they are engaging in healthy financial practices to ensure long-term viability and, potentially, a healthy return as well.