-

Solutions

- Solutions

- Individuals

-

Retirement Plan Sponsors

- Retirement Plan Sponsors

- Corporations

- Educational Institutions

- Healthcare Organizations

- Nonprofits

- Government Entities

- Endowments & Foundations

- See All Solutions

Comprehensive wealth planning and investment advice, tailored to your unique needs and goals.Investment advisory and co-fiduciary services that help you deliver more effective total retirement solutions.CAPTRUST provides investment, fiduciary, and risk management services for nonprofit organizations. -

About Us

- About Us

- Our People

- Our Story

- Learn About CAPTRUST

-

Locations

-

Resources

- Resources

- Articles

- Podcasts

- Videos

- Webinars

- See All Resources

The Biden-Sanders Unity Task Force Recommendations on the Biden campaign website say that estate taxes should be raised back to the historical norm. In other words, if Biden has his way, estate taxes would increase. That means more of a person’s estate would go toward federal taxes, leaving less for heirs and other beneficiaries.

Even if such a plan were to fail in Congress, there’s another issue to consider: The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. That law, enacted in December 2017, more than doubled the amount of assets that can be shielded from the federal estate tax and its companion, the federal gift tax. But those provisions apply only for estates of decedents dying (and gifts made) before January 1, 2026. After that, the old, less-generous provisions return.

Then there’s the coronavirus. Much of the money the federal government has spent fighting the coronavirus—and stimulating the economy—has been borrowed. At some point, the debt must be repaid—and the federal estate tax is an easy target for raising revenue, says Financial Advisor Brodie Barnes, who works in CAPTRUST’s Salt Lake City, Utah, office.

If you have a sizeable estate, consider taking advantage of current law by reducing the size of your estate to minimize how much may be eaten up in federal taxes later on, Barnes says. “Make moves now, because things are going to change one way or the other,” he adds.

Background

When a person dies, that person’s estate may be subject to federal estate tax. The federal gift tax operates alongside the estate tax to prevent individuals from avoiding the estate tax by transferring property to heirs before dying, according to a Congressional Research Service report.

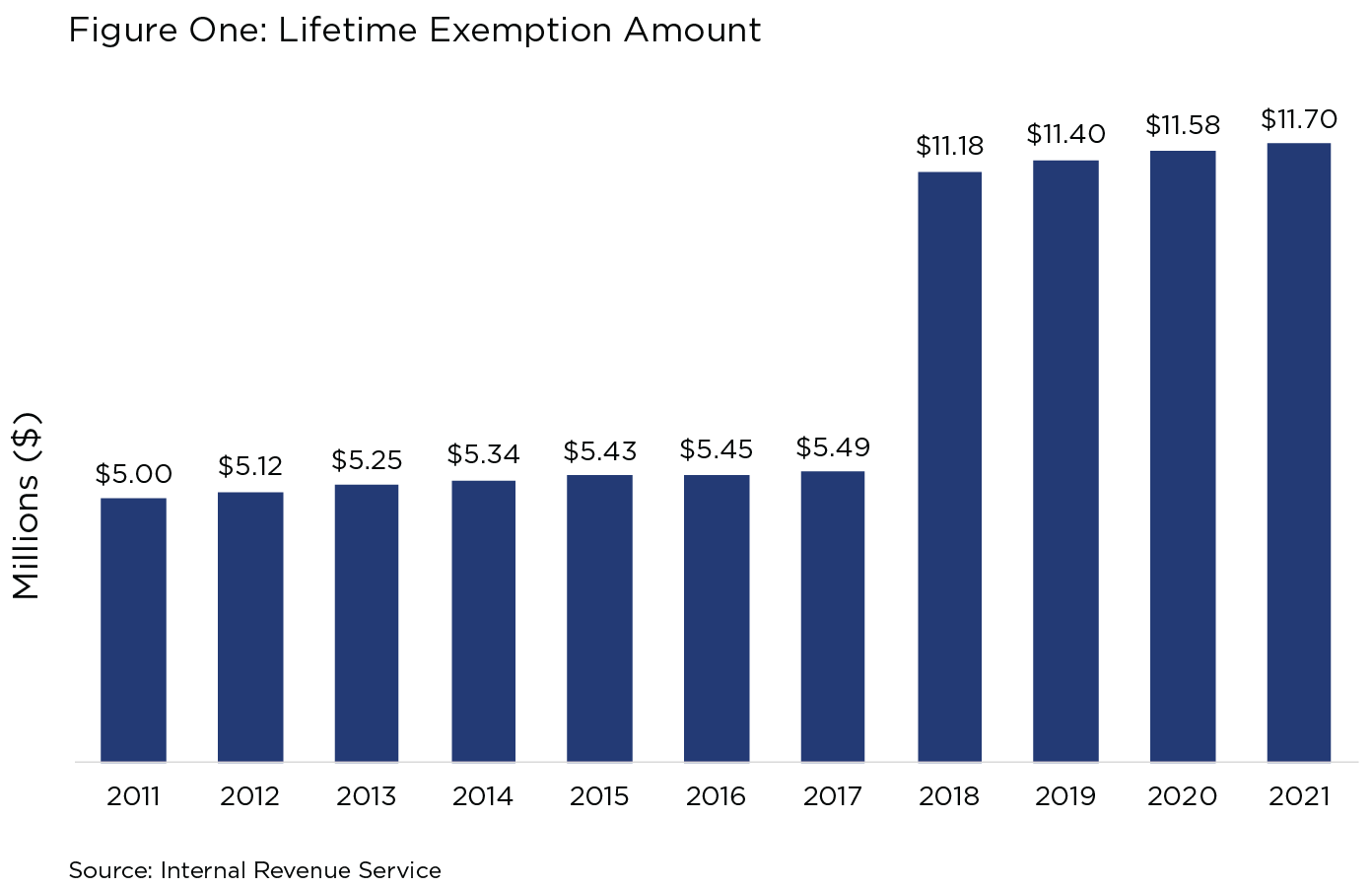

There is, however, a lifetime exemption amount. It serves to shield a certain amount of assets from both the federal gift tax and the federal estate tax. That lifetime limit, which is subject to an annual inflation adjustment, is $11.7 million for 2021, as shown in Figure One.

And there’s the rub. Under Biden’s plan, the lifetime limit would be reduced to what it was under the old law—somewhere around $5 million. Even if Congress were to reject such a plan, the lifetime limit, under current law, is scheduled to drop to an inflation-adjusted $6.5 million starting in 2026, Barnes estimates.

That’s why he recommends taking advantage of today’s higher lifetime limit. By giving away up to $11.7 million now, you move that amount out of your estate, perhaps transferring it to your children or other beneficiaries. Neither that amount, nor any future appreciation, will be subject to federal estate and gift taxes.

Suppose you do this now. When the lifetime limit drops in 2026 to about $6.5 million, will you be penalized for gifts you previously made? No. The Internal Revenue Service has officially stated that individuals taking advantage of the higher lifetime limit in effect until 2025 will not be adversely impacted after 2025 when the limit drops to prior-law levels.

Basic Steps

Before considering more complicated maneuvers, remember that you can give away a certain amount each year with no federal gift or estate tax consequences—and without even touching your lifetime limit. It’s technically known as the annual exclusion for gifts, and it’s subject to an annual adjustment for inflation. For 2021, the annual exclusion amount is $15,000, says Patricia A. Thompson, former chair of the Tax Executive Committee of the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants and tax partner at Piccerelli Gilstein & Company, LLP, of Providence, Rhode Island.

That means, for example, in 2021, you can give $15,000 to your son, $15,000 to your daughter, $15,000 to your longtime friend, and $15,000 to your helpful neighbor—for a combined total of $60,000.

If you’re married, each spouse may give up to $15,000, says Thompson. So you and your spouse can give a total of $30,000 to your nephew and a total of $30,000 to your niece for an overall total of $60,000, she says.

In each example, you’d move $60,000 out of your estate, legally sidestepping federal estate- and gift-tax consequences.

Another basic technique involves paying for someone’s education or medical expenses. There’s no dollar limit, and the beneficiary need not be related to you. But it’s important to make sure that you make the payment directly to the educational institution or healthcare provider, Thompson says.

For example, you can pay for your grandson’s law school tuition, no matter how much that is, and pay for your old friend’s medical expenses, no matter how much that is. In both instances, you would reduce the size of your estate; there would be no federal gift-tax and no federal estate-tax consequences, and you would preserve your lifetime limit of $11.7 million.

Other Options

Beyond the basic steps, consider making outright gifts to family members or others, up to the amount of your lifetime limit. This will reduce the amount of your estate that will eventually be subject to the federal estate tax—and its tax rate of 40 percent or more.

Suppose a widow has $50.3 million in assets. If she gives away an amount equal to her lifetime limit ($11.7 million in 2021), no federal gift taxes or estate taxes would apply, and she’d be left with $38.6 million to live on, Barnes says.

Some of his clients have no problem giving away large sums, he says. Others are reluctant, perhaps concerned that they may need the money later on. For them, Barnes recommends other options with more flexibility.

For example, you could make a gift to a spousal lifetime access trust, he says. That would let you move money out of your estate—taking advantage of your lifetime limit—but the assets in the trust would still be available to your spouse and other beneficiaries, such as your children, he says. To maximize this strategy and avoid certain pitfalls, he says, you could establish such a trust one year, to benefit your spouse and others; your spouse could establish such a trust the next year, to benefit you and others; and each trust would hold different kinds of assets.

Another option: Put some of your assets into a family partnership or family limited liability company, Barnes says. You could give your children an ownership stake in the entity, while you maintain overall control. The assets’ value and any associated appreciation would be removed from your estate.

The Right Fit

There are charitable options to consider, too, Thompson says, “but the client has to be comfortable giving his or her money away,” she says.

Any strategy should be part of an overall plan, and “it really needs to be customized to a client’s specific objectives and comfort level,” Barnes says. When considering such steps for clients, he says he looks at the client’s need for cash flow, the client’s charitable objectives, the type of assets the client holds, the client’s tolerance for complexity (and ongoing costs), and family dynamics. As always, before you implement any of these strategies, you should consult a tax advisor who can help you understand how they work and how they might best work for you.

While the global COVID-19 pandemic hasn’t brought us much good news, it has edged us a little further down the road to our digital health future, and many experts think that’s good. Dr. Euan A. Ashley, director of the Stanford Center for Digital Health, says the pandemic bulldozed over one big obstacle to advances in telemedicine—insurance payments—and as soon as the pandemic hit, Medicare and Medicaid began providing full reimbursement for telehealth visits.

Telehealth

Though a Zoom call might appear to keep the doctor at arm’s length from the patient, Ashley sees it differently. He says meeting with patients over Zoom during the pandemic reminds him of his childhood, when he would go with his physician father or midwife mother to make house calls. “You actually see [patients] in their home environments,” says Ashley.

He says this kind of information can really provide insight into someone’s lifestyle so he can give better recommendations on how to stay healthy. “The person who is most important is the patient, and we really have the technology to bring the medicine to them,” says Ashley.

Dr. Michael Blum, chief digital transformation officer at the University of California, San Francisco, and a practicing cardiologist, says technological advances are only one part of the equation. The technology needs social acceptance, and the pandemic has helped that along.

“The pandemic has changed the mind space about how health care is delivered,” says Blum. “Patients are now more comfortable with telehealth visits.”

Wearables

Telemedicine is just a small part of the way in which digital technology is transforming health care. Wearables are the start of being able to monitor health between visits to the doctor and detect health problems sooner. Google, Apple, and Amazon are investing heavily in the market.

Google is acquiring Fitbit, Apple has its Watch, and Amazon just released the Halo. Fitbit and the Apple Watch have Food and Drug Administration clearance for an electrocardiogram (ECG) monitor, and they can detect and notify a user of an irregular heartbeat.

Blum says he now has patients who tell him, “I have this device that is measuring my heart rate, or my Apple Watch is telling me I have atrial fibrillation.” Atrial fibrillation, or a-fib, is an irregular heartbeat that, if untreated, can be a warning sign that you are at risk for a heart attack, have an increased risk of stroke, or have another kind of heart disease.

Blum says these devices provide more than sufficient quality and amounts of data for use in making health and lifestyle decisions. However, he and other medical experts caution that any reading on these devices must be confirmed by professional-grade equipment.

There are also medical-grade wearables. For example, wearable glucose monitors and insulin pumps for diabetics can monitor 24 hours a day, seven days a week, and send data directly to your physician over the Internet. “That’s one of the chronic disease spaces that is really going to benefit [from wearables], or is already benefiting,” says Blum.

One thing both consumer-and professional-grade wearables are doing is collecting data—lots and lots of individualized data. Ashley, who is also a consultant for Apple, says that as wearables become more sensitive to changes in gait and motion, they will be used to detect early warning signs of neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s.

“It is very characteristic for a person with Parkinson’s disease to walk with a shuffling gait. People you live with don’t notice small changes. But now … we’ll be wearing devices that know us electronically over many years and recognize how we walk,” says Ashley.

Artificial Intelligence and Deep Learning

The rapidly advancing field of artificial intelligence and deep learning will help medical professionals predict who might be more vulnerable to a disease.

AI is able to sort through massive amounts of data and find patterns in a way that the human mind cannot. Data collected in hospitals and from healthcare providers can be fed into an AI system to predict the best treatment for allowing a particular individual to recover faster from surgery.

AI will be used to analyze individual DNA and protein-to-protein interactions to detect which traits are manifesting in an individual patient—an important part of the equation, since not everything in a gene sequence shows up. Blum says this will allow physicians to tailor health recommendations to the individual.

Barriers and Risks

While there is great promise and optimism about how new technologies will transform health care, there are also some barriers and risks ahead. AI and deep learning find patterns in the data. But data can reflect class differences, racial divisions, and other biases.

In his private practice, Ashley sees higher-income patients with good jobs in Silicon Valley tech firms, as well as patients from the lower-income communities of California’s Central Valley. It’s the richer patients who have a Fitbit or an Apple Watch, so it’s their data that’s getting collected. “That’s teaching the AI to begin with,” says Ashley.

There are also complex privacy and security issues that need to be sorted out as we move into the digital health age. Healthcare data is extremely valuable on the black market because it holds personal information that can be used for blackmail or identity theft. There have been numerous attacks on hospitals by hackers who have held data hostage for a price.

All the big tech companies are now looking to disrupt the healthcare industry. But their effort does raise questions about who owns the data these companies collect about you. In fact, the approval of Google’s acquisition of Fitbit has faced hurdles in Europe and elsewhere because of concerns over how the company might use the data it collects, especially when that data is combined with what Google already gathers from YouTube and its search engine.

Most physicians are moving or have moved over to electronic health records. However, you may have noticed that different doctors and health systems choose different electronic record systems, making it harder for each individual provider to get a complete picture of your medical history.

The different companies that digitize medical records have proprietary software. Blum says that for many of his patients, “I still don’t know … what happened to them previously or what’s happening now, if they go to see multiple different doctors.” In this respect, countries like the UK that have a single nationalized healthcare system are able to make better use of digital records.

Despite the hurdles, Blum says, “I’m highly confident [health care] is going to look dramatically different from the prior decade.” As Microsoft co-founder and philanthropist Bill Gates once said about the computer revolution, “You ain’t seen nothing yet.”

As he wound down a career in public relations, Tedino actively searched for ways to turn his passion for the sport into a fulfilling second act. He became a certified tennis pro and got increasingly involved with his local club.

“For me, any day on the tennis courts is a great day,” Tedino says. “I love tennis.”

These days, Tedino spends pleasant afternoons helping high school athletes improve their games as head tennis coach at St. Ignatius College Prep, a private school in downtown Chicago. He also keeps his communications skills honed as an advisor to the Chicago District Tennis Association, a board member at Lincoln Park Tennis Association, and a published tennis writer.

Tedino firmly believes people of all ages and abilities can get into the game and reap its many rewards, just as he does. “It’s such a great sport in terms of health benefits, socialization, and the ability to learn and continually improve,” says Tedino. “There is no prior experience or skill that’s needed, just the desire to learn the sport. And it’s fun to be out there playing.”

Stay Strong as You Get Older

Unlike, say, tackle football or ice hockey, tennis is truly an activity that can be enjoyed for a lifetime—and it pays enormous dividends in physical fitness as you get older. Tennis involves vigorous use of the upper body and core as much as the lower body. Working out the full range of muscle groups is vital for staving off age-related muscle loss.

Playing tennis regularly is associated with heart-healthy factors like lower body fat, better cholesterol levels, and aerobic fitness. Tennis players tend to have stronger cardiovascular, metabolic, and bone health. They also often exhibit more agility, balance, and coordination than nonplayers.

Keep Your Brain Sharp

Concentrating intensely on that fast-flying ball forces your brain to quickly size up a multitude of different variables. “In addition to the physicality of it, your mind is constantly working,” says Tedino. “If you’re playing singles, it’s just you, figuring out how to win points against your opponent. Tennis teaches people how to problem solve.”

It’s a feat to simultaneously consider the angle of the bounce, speed, and physics so you can line up your body in the right way to direct the ball where it should go. “You have to develop resilience and have a really good mental attitude,” says Tedino. “You have to be able to shake off the errors, get them out of your mind, and keep going.”

Promote Longevity

Tennis has been called the single best sport for a longer life. A 2017 British study found that regular players of tennis and other racket sports tended to live longer, not only compared to sedentary people, but also compared to people who exercised solo through jogging, swimming, or biking, The New York Times reported.

Another study followed in 2018, in which Danish researchers observed over 8,000 participants for about 25 years to compare the effects of a variety of sports on longevity. Again, tennis was a clear winner, associated with an astonishing 9.7-year-longer life span. By comparison, badminton was shown to add an average of 6.2 years to life expectancy; soccer, 4.7 years; cycling; 3.7 years; swimming, 3.4 years; and jogging, 3.2 years.

One possible explanation the researchers offered was that tennis mimics interval training, an especially efficient form of exercise characterized by a mix of high- and low-intensity bursts of exertion. This type of physical workout is believed to improve health more than moderately paced efforts like walking or jogging.

Foster Friendships

Another reason tennis may pack an extra wallop for health is that it involves being with other people. Humans thrive on social interaction and companionship. Getting outside, talking, and bonding with friends provides nourishment for the soul and an all-important sense of belonging. Supportive relationships naturally arise when you play tennis with friends, join a club, or organize a regular tennis meet-up with a partner.

Over the summer, Tedino was at a mixed-doubles event when he met a woman in her 70s. “She had picked up tennis in her 40s,” he says. “She’d gotten remarried, and her new husband played a lot of tennis. She said that as a kid, she couldn’t throw, couldn’t catch, and had always been picked last in all sports, so her goal was just to learn enough tennis to be able to say yes to someone if they asked her to play.”

She practiced, took lessons, and eventually became a solid player, making a lot of friends along the way. Years later, “She’s actually now a widow,” Tedino says. “She’s been able to maintain her social connections through tennis. Tennis is something that brings you together. You’ve got this activity, and then you go out for lunch or a drink afterward. It’s not just for older people—it’s for everybody.”

Relatively COVID-19 Safe

While the COVID-19 crisis has put a damper on people’s ability to stay active or get to the gym, tennis is particularly well suited to play during a global pandemic. When you’re outdoors on a court that measures 36 feet by 78 feet, it’s easy to stay a healthy 60 feet apart in a singles game. Doubles is often played with a spouse or a household member, though you can still keep well apart without much effort.

“Tennis is a sport where you can maintain social distancing without being socially distant,” says Tedino. “With [COVID-19], we’ve had an outpouring of people wanting to play. At my tennis club, we have bookings sunup to sundown every single day of the week.” Many people are working from home, so “they can steal an hour or two with a friend and head back in time for the next Zoom meeting.”

The United States Tennis Association (USTA) has a set of recommendations and guidelines on its website for playing tennis as safely as possible, including wearing masks appropriately, avoiding high fives, observing distancing rules, and leaving the area as soon as possible after your game is over.

Anyone Can Play

People of any age can play, and even play competitively. “Anyone with reasonably good mobility and eye-hand coordination can play,” says Tedino. “You don’t have to be particularly athletic, although fitness from other activities will serve you well on the court.”

The International Tennis Federation sponsors world competitions for seniors age 50 to 64 and super-seniors 65 and up. (In competitive tennis, players in their mid-30s and 40s are categorized as young seniors.)

Even if you’re mobility-impaired, don’t rule out tennis. “An area that has taken off is wheelchair tennis for adults or kids,” says Tedino. “It’s the exact same game, except wheelchair tennis players are allowed to have the ball bounce up to twice before they hit it.” There are wheelchair tennis programs around the U.S., and wheelchair tennis players have competed in the Paralympic Games since 1992.

To get started, all you need is a racket, a good pair of shoes, and some tennis balls. To find an appropriate racket, “Go to your local tennis or sporting goods store and get a mid-priced racket with the right-sized grip for your hand,” Tedino says.

No special clothing is required—just comfortable tops and bottoms that are breathable. Pockets are helpful for holding a tennis ball. If you’re older, investing in a good pair of supportive shoes is essential.

“I’d start out spending more money on shoes than a tennis racket,” says Tedino. “Don’t try to play tennis in running shoes, because you do a lot of side-to-side movement on the tennis courts.” Running shoes aren’t made for that.

To find beginner lessons and to find people with similar skill levels to play with, “Most people can find a way to get into tennis through a local parks and recreation department,” says Tedino. “Many cities offer instruction on weekends or in the evening. Tennis clubs do the same thing.”

The USTA website also has helpful information on its local chapters around the country. So, it might be time to consider picking up a tennis racket and trying out your swing. It’s a hobby that could add years—and years of fun times—to your life.

Historically Disconcerting

With all that happened last year, it’s easy to miss the fact that the major stock market indexes—the S&P 500 Index of large U.S. companies among them—reached record levels last February. Up to that point, things seemed to be going well, with the markets set for another solid year of gains. Just a few weeks later, as news of the novel coronavirus crept into the headlines, the tone began to change.

On Monday, March 9, the markets experienced a tsunami of selling, resulting in a 7.6 percent drop in the S&P 500 Index. At the time, that was the largest single-day point drop in the index’s history. Not to be outdone, March 12 and March 16 both set new records, with the index falling 9.51 and 11.98 percent, respectively. In fact, eight of the 20 largest point declines in the S&P 500’s nearly 100-year history happened last March.

Of course, the market didn’t go straight down. March also witnessed eight of the top 20 largest single-day point increases in S&P 500 history, including big bounces on the days after those historic drops.

While investors fret less about big gains than big losses, they count as volatility too and can be equally confusing. In the fog of war, it’s tough to see clearly.

Different This Time?

Last year proved to be a very bumpy ride that challenged the patience of even the most seasoned investors. The fact that all of this market turmoil happened amid—and perhaps because of—stay-at-home orders, rising virus case counts, skyrocketing unemployment, and social and political tensions made it seem like it really would be different this time. But it wasn’t.

While the details change, the story is always the same. Markets don’t like uncertainty. This is true of all markets—stock and bond markets around the world and currency and commodity markets. When a new uncertainty rears its ugly head, markets react. The uncertainty could be political (e.g., an election outcome or federal budget impasse), geopolitical (e.g., trade negotiations or terrorist attacks), economic (e.g., pandemic lockdown or Federal Reserve policy change), or natural (e.g., hurricanes or earthquakes).

It’s the surprise that matters. Markets need time to recalibrate, finding new levels as they seek to understand the practical impacts of a new reality. In the beginning, when little is known, different investors or analysts may have wildly different views—or they may just be reacting to take risk off the table—resulting in significant levels of volatility. The bigger and more complex the uncertainty, the more volatility.

Over time, views converge as more information becomes known, or, as the range of possible outcomes starts to narrow, volatility subsides. If you need an example, just recall how little we knew about the virus and its effects on society and the economy last spring versus what we knew at year-end.

Of course, realizing this doesn’t make it easier. Even normal levels of volatility—a 10 percent pullback every year or two—can be disturbing and cause investors to question their strategies, especially as they get older. The thought of a major market pullback in the last few years before retirement is enough to cause many to move to the sidelines. And yet that’s a very bad idea.

Boring for the Win

Even as you approach retirement age, you still need to think like a long-term investor. A 65-year-old woman has a life expectancy of 86.6 years; a man the same age has a life expectancy of 84.1 years. That’s a minimum of 20 years to plan for. And remember: Life expectancy is an average. There is a very good chance that you will live longer than that. Perhaps a lot longer.

With interest rates at or near 0 percent, riding out a couple decades in cash is not viable. So how exactly can you get comfortable investing in stocks, knowing that volatility is inevitable? The answers to this question will sound like clichés. They are boring, but that does not mean that they lack merit or are untrue.

Spread It Around

Diversification, investing in a variety of asset classes, is both the single biggest investing cliché and single best way to preserve and grow wealth. True, diversification means that you will never hit it out of the park, but it will help dampen risk and reduce the impact of a stock market pullback on your portfolio. Bonds, in particular, have historically been a powerful portfolio stabilizer and continue to add value, even at today’s low interest rates.

There is also a behavioral trick here. Any individual investment or asset class may be volatile at a given moment. However, viewing your portfolio in aggregate—rather than focusing on a single component—will help moderate your fight-or-flight instinct when volatility rises.

Make a Plan

Investing for your major life goals without a financial plan is like going on a road trip without a map—or, these days, your smartphone. You might get there, but it will probably take a lot longer than you expected.

A solid plan will help you understand the income, expenses, and portfolio mix that will get you where you want to go and help you understand best-case, worst-case, and expected outcomes given a range of portfolio returns and market conditions. Done properly, a financial plan will provide you with a sense of purpose—you know where you’re going and what you need to do to get there. When the markets get rocky, revisiting your plan can provide a sense of confidence that the goals you have set remain achievable.

Find Your Sweet Spot

Putting it bluntly, if your money is keeping you up at night, you should consider how aggressively you’re invested. An investment strategy that is too exciting may be difficult to stick to for the long haul. And that’s important because staying invested in the stock market is how you generate returns.

Missing even a few days can drastically reduce your return. For example, in 2020, stocks (as measured by the S&P 500 Index) returned 16.3 percent. If you missed the best day of the year, that return falls to 6.3 percent. It falls to -19.3 percent if you missed the best five days.

Put It on Autopilot

Our aversion to losses means that, for most people, investing is fraught with angst and emotion. A couple of rules-based strategies that keep your emotions from getting in the way might help.

Knowing when to put money to work is always a difficult question. Is this the bottom? Should I wait for the inevitable pullback? Dollar-cost averaging is a popular strategy for investing cash by splitting it up into a series of installments over a predetermined period, typically months or quarters. While studies report that investing via a single lump sum can be just as effective, systematically investing via dollar-cost averaging can both be efficient and assuage fears of getting in at the wrong time.

Over time, a portfolio can stray from its original risk level. For example, if stocks outperform bonds over time, they become a larger relative portion of your portfolio, and it becomes riskier; if bonds outperform stocks, it becomes less risky. This is completely normal because different investments will perform better or worse in different markets or economic conditions. That’s when rebalancing—a process of systematically selling some of your outperformers to invest in the underperformers—comes in. There are many ways to implement rebalancing that have merit, but they are all designed to keep your portfolio risk on target over time via small, incremental moves.

Scratch the Itch

When the markets get volatile—as they are certain to do from time to time—it’s OK to spring into action. Focus on facts, and don’t act rashly or out of emotion. Ask your financial advisor to rerun your financial plan to make sure you’re still on track for your goals. Take a look at your portfolio’s risk level, and dial it in, as appropriate. Use a pullback as a time to rebalance. Put some of your sideline cash to work in the most beaten-up asset class. Taking action to exert some control over your situation will make you feel better and can turn a crisis into an opportunity.

As the saying goes, “May you live in interesting times.” At first blush, that sounds exciting—a blessing even. But, ideally, your life is more interesting than your money. In fact, when it comes to long-term investing, boring is vastly underrated.

Q: Why hasn’t the explosion in government debt caused a problem for the market? When will it?

A: If the skyrocketing national debt level keeps you up at night, you’re not alone. Many investors have been concerned about elevated debt levels and their effects on the economy, especially since the two pandemic-related stimulus bills have caused it to soar by more than 25 percent.

In the U.S., fiscal stimulus and relief programs in 2020 are estimated to exceed $4 trillion, or nearly 20 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). With an expansion of unemployment benefits, monetary support going directly to households, grants and forgivable loans going out to small businesses, and support to hospitals and health agencies combating COVID-19, the relief programs are targeted at limiting economic damage while supporting virus containment efforts until widespread vaccination is available.

During a crisis, there is no alternative to acting quickly to limit the damage—and markets have so far cheered the actions of policymakers. However, government spending on this scale raises questions about the long-term effects of a growing national debt. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that the federal budget deficit will reach $3.3 trillion in 2020, a level (as a percentage of GDP) that has not been seen since World War II. This follows on the heels of a $1 trillion budget deficit in 2019.

One risk of our swelling national debt is higher interest rates. If investors were to become less comfortable lending money to the U.S. government to finance its deficits, they would require more compensation in the form of higher interest rates. Higher rates, in turn, would increase the cost of carrying such high levels of debt and serve as an impediment to growth that leads to even more borrowing and so on.

Fortunately, this scenario is less likely to occur in the U.S. than in other parts of the world, because of the U.S. dollar’s enviable position as the world’s reserve currency. Global demand for dollar-denominated assets serves as a steady source of demand for Treasury bonds, keeping interest rates—and therefore borrowing costs—low.

Another consequence of higher debt levels is the risk that servicing the debt reduces our country’s ability to invest in other important areas, such as education, research, infrastructure, defense, and combating climate change, which could harm our competitiveness on the world stage.

Finally, there is the risk of inflation. Policy tools can be imprecise, sometimes with delayed effects—leading to the risk of an overshoot if stimulus that is applied with the intent of limiting economic damage winds up overheating the economy.

The same concerns were expressed in 2008 when a collapse in housing prices triggered a global financial crisis. During that time, we saw (albeit smaller in scale) similar monetary stimulus but no inflation. Also noteworthy, despite decades of large deficits and low or negative interest rates, inflation has not become a problem for Japan.

Economists are divided on the severity of these risks. Some believe that debt concerns are overblown, while others claim that increased debt places our privileged global position at risk. Either way, the debt issue (and this debate) is likely to extend well into the future, as an economy that continues to recover would be less tolerant of higher taxes or reduced spending.

Q: My spouse and I are talking about divorce. What kind of changes should I anticipate around insurance coverage?

A: Few life changes are more consequential than a divorce. In addition to the financial and emotional challenges of ironing out a settlement, attending court hearings, and dealing with competing attorneys, you’ll also face special concerns about your insurance coverage. Since there’s a lot going on during a divorce, insurance may not be top of mind, but it’s important to be aware of how you and your family will be impacted.

Planning for these changes should begin long before the divorce is final. And because it’s common for one spouse to maintain employer-provided insurance for the family, the breakup of a marriage can have serious insurance consequences for the other spouse and young children in the family, especially if he or she was not employed outside the home.

Health Insurance

Often, one spouse participates in a group health insurance plan at work that provides coverage for both spouses. When a divorce occurs, coverage for the other spouse will often end, unless the divorce decree requires continuation of coverage.

If there is no such requirement, temporary protection may be provided by the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (COBRA). This federal law protects employees of companies with 20 or more workers and their dependents from losing group insurance coverage as a result of job loss or other life changes like a divorce. Certain governmental and nonprofit enterprises are exempt.

If your ex-spouse maintained family health coverage through work, you may, at your own expense, continue this group coverage for up to 36 months, or until you remarry or get coverage under another group health plan.

If you are eligible for health insurance through your own employer, talk to your human resources department about your options. This can be more cost efficient than COBRA and keeps you out of your ex’s company plan. Although you generally have to wait for certain times of the year to join employer health insurance, losing your previous coverage due to a divorce launches a special enrollment period for you to sign up for your employer’s plan.

Life Insurance

If you’re a custodial parent, make sure the life of the noncustodial parent is insured. You don’t want to end up in a position in which child support payments suddenly end because an ex-spouse dies. The same principle applies to alimony payments. Life insurance can protect you and your children in case of untimely death. If you have trouble paying the policy premiums, you can petition the court to have alimony and child support payments increased to cover the cost.

If you don’t have custody of your children, you’ll still want to insure the life of your ex-spouse. If he or she were to die, you would likely gain custody of your children, increasing your expenses dramatically. If you can’t get new insurance on your ex-spouse, have his or her existing policies transferred to you as the new policyowner and beneficiary. This can be planned as part of the divorce agreement.

Disability Income Insurance

If you receive alimony or child support, another risk to your income may arise if your former spouse becomes disabled. If he or she has no disability insurance and is unable to work, the court may modify the alimony and child support obligation, reducing or eliminating payments to you.

With a disability policy, your ex-spouse will receive benefits each month and may be capable of paying the same amount of alimony and child support. Planning for disability insurance should be completed before the divorce is final. Unlike life insurance, you can’t own a disability policy on someone else. So, the divorce decree may require that your ex-spouse pay the premiums on a policy and that you are entitled to regularly receive proof that the policy is in force.

Property Insurance

At a high level, you’re going to have three options when changing your home insurance after a divorce: You can cancel your joint policy, you can take a person off of your shared policy, or, if you’re ordered to stay in the same dwelling, you can keep the coverage the way it is. However, there are a few different things that you’ll have to do to for each scenario.

Canceling your joint policy will be a group effort—your insurance agent will require consent in writing from both ex-spouses. This method will probably work best if you are both leaving the house and going your separate ways.

If you’re the primary policyholder, you can remove your ex-spouse from the policy by giving your insurance carrier a copy of your divorce decree. If you’re not sure who the primary policyholder is, it’s usually the person who called in to set up the policy (even if you’ve both signed the deed, loan, or policy). If you are not the policyholder, the options you’ll have are to prove that you have insurable interest, remove yourself from the policy, or arrange to be the responsible party for the insurance payments.

Insurance Beneficiaries

During or after a divorce, your choices on beneficiaries may be somewhat limited. For example, if a court ordered that you must continue an existing policy with your ex-spouse as beneficiary, you cannot change it. If you’re under no such constraints, however, your choice usually boils down to either your estate, your ex-spouse, or your children.

Designating your estate as beneficiary will tie up the insurance proceeds in probate. And unless you need to protect alimony or child support payments, you probably have no need or desire to name your ex-spouse as beneficiary. Designating your children as beneficiaries may be your best course but doing so can be very complicated if they are minors. One solution is to create a trust for the children and name the trust as beneficiary.

Remember: Divorce laws may differ from one state to the next, so consult an experienced legal professional before proceeding. Your situation is unique, so make sure that you also sit down with your financial and tax advisors to make sure that your plan is right for you.

Many life insurance policies may not be funded with adequate premiums to keep coverage in force until death. In recent years, the risk of underperformance for many policies has been shifted from the life insurance carrier to the policy owner and the trustee as fiduciary.

Investment returns and non-guaranteed expenses are often not clear from the annual policy statements provided by the insurance carrier. This is particularly a problem for trust-owned life insurance where the professional or amateur trustee is under a fiduciary duty to manage the risks and monitor the performance of the trust policies.

Trustees of trust-owned life insurance policies are guided by the Prudent Investor Act, which requires those who have control over another’s assets to acquire investments or manage the funds in such a way that the holdings are only exposed to risks that a reasonably intelligent and cautious person would consider worthwhile. They must, in other words, have a low probability of permanent or long-term loss.

A fiduciary that breaches the Prudent Investor Act can be held responsible for damages and recovery of losses incurred by inadequate life insurance acquisition processes, ineffective ongoing management, or inappropriate investment strategies. If a policy lapses before the insured’s death, the trustee may be held responsible for, among other things, not properly reviewing and managing the policies.

For trusts that own policies, annual life insurance reviews that include in-force illustrations and appropriate benchmarking are essential. The trustee should follow appropriate guidelines and procedures for managing the policies, including keeping detailed records, illustrations, notes, and actions taken at review meetings.

Financial advisors who have expertise in managing life insurance can assist with providing a comprehensive review. Insurance carriers do not provide comprehensive reviews or advice.

Without professional management, the policy owner may be required to pay substantially higher future premiums and may be at increased risk of the policy lapsing prior to the insured’s death. A life insurance portfolio review can identify policies that are underperforming and that may lapse or require dramatically higher premiums in the future.

In many cases, improvements can be made to an existing policy. Alternatively, improvements may be achieved by comparing to policies offered by the other insurance carriers. This can result in lower premiums for the same amount of coverage, more coverage for the same premium, or more predictable premiums with less risk.

On October 30, the Department of Labor (DOL) released a final rule under the name Financial Factors in Selecting Plan Investments. This rule amends certain provisions of the investment duties regulation applicable to plans covered by the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) by providing guidance for fiduciaries to follow when selecting and monitoring investments. The rule makes it clear that plan sponsors must never subordinate investment returns or increase investment risk due to nonfinancial factors.

The proposed rule, originally issued in June, garnered a lot of attention from asset managers and plan sponsors. While the final text of the rule does not specifically identify environmental, social, and governance (ESG) investments in ERISA-covered plans and instead focuses only on nonpecuniary factors, the DOL’s preamble to the final rule makes it clear the intent is to clarify long-standing confusion regarding how fiduciaries can incorporate ESG into their plans and respond to a rise in popularity of ESG-themed investments.

Historically, plan sponsors have relied on numerous pieces of subregulatory guidance on this subject, dating back to 1994. However, the historical guidance became ambiguous and changed with presidential administrations.

The final rule includes the following core additions to the current investment duties regulation:

- A specific provision to confirm that ERISA fiduciaries must evaluate investments and investment courses of action based solely on factors that the responsible fiduciary prudently determines are expected to have a material effect on risk and/or return of an investment based on appropriate investment horizons consistent with the plan’s investment objectives and the funding policy.

- This provision also states that the duty of loyalty prohibits fiduciaries from subordinating the interests of participants to unrelated objectives and bars them from sacrificing investment return or taking on additional investment risk to promote nonpecuniary goals.

- Explicitly requires fiduciaries to consider reasonably available alternatives to meet their prudence duties under ERISA.

- New regulations on required investment analysis and documentation requirements for those limited circumstances in which plan fiduciaries may use nonpecuniary factors to choose between or among investments that the fiduciary cannot distinguish based on pecuniary factors alone.

- States that the prudence and loyalty standards set forth in ERISA apply to a fiduciary’s selection of a designated investment alternative to be offered to plan participants and beneficiaries in a defined contribution plan. The rule does not categorically prohibit the fiduciaries of such plans from considering or including, as designated investment alternatives, investment funds, products, or model portfolios that support nonpecuniary goals if the plans allow participants and beneficiaries to choose from a broad range of investment alternatives, as defined in 29 C.F.R. § 2550.404c-1(b)(3). However, the rule makes clear that the fiduciaries must first satisfy the prudence and loyalty provisions in ERISA and the final rule, including the overarching requirement to evaluate investments solely based on pecuniary factors when selecting any such investment fund, product, or model portfolio.

- Prohibits plans from adding or retaining any investment fund, product, or model portfolio as a QDIA (as described in 29 C.F.R. § 2550.404c-5), or as a component of such a default investment alternative, if its objectives or goals or its principal investment strategies include, consider, or indicate the use of one or more nonpecuniary factors.

The final rule will become law 60 days after publishing in the Federal Register. However, the new rule remains subject to the Congressional Review Act, which allows Congress to strike down federal regulations within 60 legislative days.

Importantly, the rule will apply only on a prospective basis, meaning fiduciaries will not have to divest or cease any current investment, even if originally selected using non-pecuniary factors in a manner prohibited by the final rule (with the exception of the prohibition of QDIA investments that use nonpecuniary factors as a primary investment objective, which must be removed from plans by April 30, 2022). However, plan sponsors still maintain responsibility for any actions or decisions made prior to the enactment of this rule and subject to their fiduciary duties of prudence and loyalty in effect at the time.

For more information, please contact your CAPTRUST Financial Advisor at 800.216.0645.

The movie opens with this pithy and prescient quote (erroneously attributed to Mark Twain): “It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.”

No doubt Adam McKay, the film’s director, was making a statement about the massive financial risks hiding in plain sight in the mid-2000s while the rest of the world remained oblivious to the imminent collapse. In hindsight, a growing housing bubble, lax bank lending standards, and risky mortgage products were obvious warning signs.

But if these risks were there to be seen by everyone, why did so few people notice and sound the alarm? Why were the rest of us caught off guard?

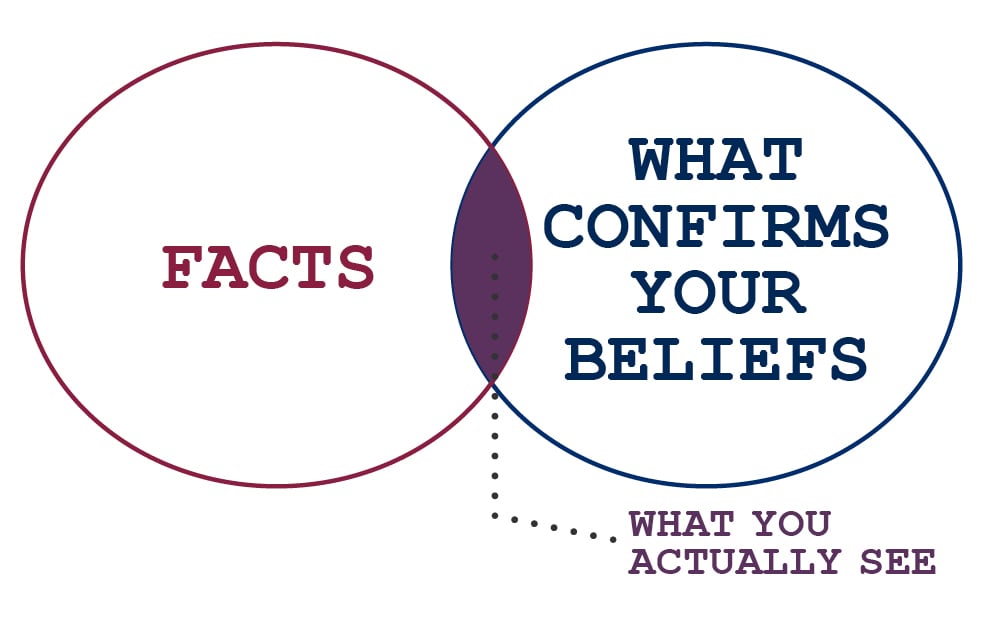

The answer: The rest of us saw what we wanted to see, a growing economy with rising stock prices and real estate values. This phenomenon is known as confirmation bias, one of several behavioral biases that affect us all.

Confirmation bias is at work when we look for, interpret, and remember information in a way that confirms our existing ideas. No matter how impartial we believe ourselves to be, we cannot help but favor information that supports what we already believe (or want) to be true. It contributes to overconfidence in personal beliefs and can support or strengthen beliefs—even in the face of contrary evidence.

For it is a habit of humanity to entrust to careless hope what they long for, and to use sovereign reason to thrust aside what they do not fancy.

Thucydides, Greek historian

Find What You’re Looking For

Many examples of confirmation bias’s influence exist in our day-to-day activities. For example, if you decide to buy a car and fall in love with the look of a particular model, you will certainly find ample evidence—reviews, videos, celebrity endorsements, whatever—to confirm your desire. Conversely, if your dinner date suggests a restaurant that you’re not wild about, you can easily find ample evidence of poor service and bad food.

Confirmation bias can also create costly mistakes for investors. Imagine talking to a friend at a party. He shares with you his latest money-making stock idea and suggests that you check it out—but don’t wait too long, he says, or you might miss out on a big move. Because you are a savvy investor, you jump on the Internet and do your own due diligence.

Unfortunately, confirmation bias causes your brain to latch on to information that supports your friend’s suggestion. Meanwhile, it rejects data that goes against your beliefs. Your research complete, you make your trade the next day. A week later, the stock tanks on a disappointing earnings release.

We’ve all done it, and it’s not our fault. Confirmation bias is tricky to detect in ourselves.

While the Internet certainly enables it, social media has amplified confirmation bias in recent years. Social media platforms like Facebook use algorithms to target users with content that they will agree with—and exclude content they are likely to oppose. The content presented strengthens one’s views, resulting in what experts call filter bubbles, where an individual becomes closed off to new ideas, subjects, and information.

But confirmation bias is not all bad and, like many behavioral biases, likely developed to help our ancient ancestors cope with the world. It drives us to surround ourselves with people who share our values, traditions, religious beliefs, and political leanings. The upside is that this behavior leads to more enjoyable and fulfilling lives as we surround ourselves with like-minded people who validate the way we live.

But how can we know the difference between a positive effect and a negative effect? And what can we do to make sure we are making better decisions?

What the human being is best at doing is interpreting all new information so that their prior conclusions remain intact.

Warren Buffett, American investor and philanthropist

Hold on Loosely

The best cure for confirmation bias’s negative effects is to hold onto your opinions less tightly. But that, of course, is easier said than done. Here are a few tips and tricks that might help:

Stew on it. Don’t act immediately. Giving yourself time to conduct research, talk to experts, and seek out different or opposing points of view can reduce the risk of confirmation bias. Take it all in and refuse to jump to conclusions. Put it in the stew, let it simmer for a while, and draw your own conclusions.

Be humble and open to change. Recognize that you don’t know everything and practice humility when listening to others. As the saying goes, “We have two ears and one mouth so that we can listen twice as much as we speak.” Give yourself permission to change your mind as you encounter new information on a topic.

Challenge your thinking. Confirmation bias partly explains why two people can see the same information or fact pattern and come to opposite conclusions—and neither will be completely correct. Make it a personal policy to seek opposing views or other possible explanations to problems or topics you’re exploring. The more viewpoints the better. This will add nuance to your thinking and help you draw richer conclusions.

Find a sparring partner. Whether it’s your spouse, best friend, or a trusted colleague, find someone to become your thinking partner. Authorize him or her to challenge your views by playing devil’s advocate—and return the favor. Many people process their thinking by speaking, so having a trusted sparring partner to debate—one who won’t judge you—can be a helpful way to expand your thinking.

In our role as financial advisors, we often act as thinking partner with our clients when they find themselves in a filter bubble.

Most recently, during the depths of the COVID-19-related market sell-off in March, we found ourselves helping clients manage fight-or-flight responses induced by their fears of lost money and stoked by an inflammatory news media. The fire was further fueled by the virus’s then-unknown impact on lives and our healthcare system.

In most cases, our counsel and long-term perspective on the markets and investing helped expand clients’ thinking enough to stifle their knee-jerk reactions. And time has brought new information—on the virus, economy, and markets—to the discussion that has tempered reactions.

Whether you are hoping to become a better investor, a better businessperson, or just a better thinker, overcoming behavioral biases is a challenge—but one worth accepting. If philosophers, astronomers, and scientists had been closed to new information, we would still believe the world is flat and that the sun revolves around the Earth.

Thinking for yourself doesn’t require you to follow every new idea that comes along. It simply means being humble enough to realize that no matter how much you know, a fair amount of what you know for sure just ain’t so.

“There’s no question we all do not age at the same rate—just go to a high school reunion and look around,” says S. Jay Olshansky, a professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Slow biological aging is what we perceive in a friend who looks younger than her chronological age. Fast biological aging is what we fear when we say stress has taken years off our lives.

In 2020, biological age is more than just a feeling—it’s a science. Researchers are developing new ways to measure it. They also are working on ways to slow it down with drugs, dietary regimens, and other approaches. They don’t expect to cure aging, “but what we’d like to do is change the rate at which that happens so that, in 20 years, you might age 10 years,” says Steven N. Austad, a distinguished professor and biology department chair at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

We aren’t there yet, he and other researchers say. But we already know enough for all of us to take biological aging seriously and to try to do something about it while the scientists keep working on better braking systems.

Differences Start Early

Young adults often live like they are invincible, and most are outwardly pretty healthy. They are free of deep wrinkles and gray hair and have yet to develop any chronic ailments. But researchers have discovered something that might startle many young people. By their late 30s, some will be biological 60-year-olds.

That was the conclusion of a study of nearly 1,000 people born in the same New Zealand hospital in the same year. Using 18 different biomarkers—measurements that included cardiorespiratory fitness, body mass index, cholesterol counts, liver and kidney tests, immune status, and even gum health—researchers compared participants at ages 26, 32, and 38.

While most people aged about 1 year biologically for each calendar year, some aged more than twice as fast and some aged barely at all. At 38, their biological ages ranged from 28 to 61. Rapid agers felt older, according to their own health reports, and looked older, according to strangers asked to guess their ages. They also did worse on tests of physical and mental agility.

Those striking results upended the view that aging differences begin much later in life, says researcher Daniel Belsky, assistant professor of epidemiology at Columbia University.

There are a lot of studies that show about 25 percent of how healthy you remain and how long you live is due to genetics, which you can’t control. The rest is due to environment, much of which you can control.

Steven N. Austad

The differences that start in young adulthood accelerate from there. By their mid-70s, “some people are bedridden, while others are active and working,” says Eric Verdin, president and chief executive officer of the Buck Institute for Research on Aging.

“What happens when you are 70 is a reflection of things that have been happening to you throughout your life,” says Verdin.

Our bodies “are constantly subjected to stress and damage,” Verdin says. Mental and physical trauma, gravity, radiation, and other forces take a daily, invisible toll. Still, most of us manage to function well and recover from illness and injury for many decades, thanks to repair mechanisms built into our cells.

“What happens is that the repair mechanisms eventually become damaged and we get into trouble,” Verdin says.

Trouble tends to begin sooner in people with a history of stressful childhood experiences, such as poverty and abuse, according to research by Belsky and others.

Well-known health risks, such as smoking, obesity, and poor diets also speed up aging, research shows. Genes matter, but maybe not as much as people assume.

“There are a lot of studies that show about 25 percent of how healthy you remain and how long you live is due to genetics, which you can’t control,” says Austad, the Alabama researcher. “The rest is due to environment, much of which you can control.”

We can affect our aging rates, even in our 60s and beyond, Austad says, with basic healthy habits and, perhaps, some still-experimental interventions. Belsky agrees but adds, “It can be true that it’s never too late, but also be true that to get the best response, it’s best to start early.”

Testing, Testing—How Old Are You Really?

Of course, most of us don’t know our biological ages. That suggests there’s both a scientific need and a commercial market for more streamlined tests. Several have been developed.

For example, consumers have long been able to buy blood or cheek-swab tests that estimate biological age based on the length of telomeres, the protective caps at the ends of chromosomes. In studies of large groups of people, short telomeres are associated with short lives. But the measure has never been shown to accurately track individual aging rates.

“The telomere length thing was a bit of a fad,” says David Stewart, founder of a media company called Ageist. Stewart recently tried a newer kind of test.

He sent off a saliva sample to a company called Elysium Health. The company is one of several that sell tests to consumers based on epigenetic markers—chemical tags that attach to the DNA in our cells, turning genes on and off. While our genes do not change as we age, these epigenetic markers do. Certain epigenetic patterns are thought to reflect not only the ravages of time but the cumulative effects of our habits and environments. Scientists have developed aging trackers, dubbed epigenetic clocks, based on these patterns.

According to the Elysium test called Index, the 61-year-old Stewart is biologically 54. “I thought I was doing OK, but I didn’t know,” says Stewart, who swears by a low-glycemic diet, intense exercise, and plenty of sleep. “Now I know I’m doing OK. That’s a good data point.”

But consumers considering shelling out $499 should know that the test has not been reviewed or approved by the Food and Drug Administration and can’t predict longevity or the risk of any disease. The same is true of other aging tests on the market.

The test is intended to give you a snapshot of how quickly you’ve aged so far, says Morgan Levine, bioinformatics advisor for Elysium.

“It’s a readout of how you are doing, almost a report card for your health,” she says. While Levine hopes users will be inspired to maintain or add healthy habits (and take follow-up tests to track their progress), she does not have data showing that changes in health habits can alter future results.

Several other aging tests are under study. Some, used in research labs, look at blood proteins that change with age. One experimental test uses a scanner to look for signs of molecular aging in the lenses of your eyes.

Another idea: Using a computer program to analyze facial features that change with age. Olshansky, the Illinois aging researcher, is a leading promoter of that concept.

Verdin, of the Buck Institute, says he’s tried a variety of lab and photographic tests and, at age 63, consistently tests about five years younger. “I take it as a sign that I might be doing something right.”

Doing the Right Thing—and Wondering What’s Next

We all want to do the right things to slow down aging. So, what are they?

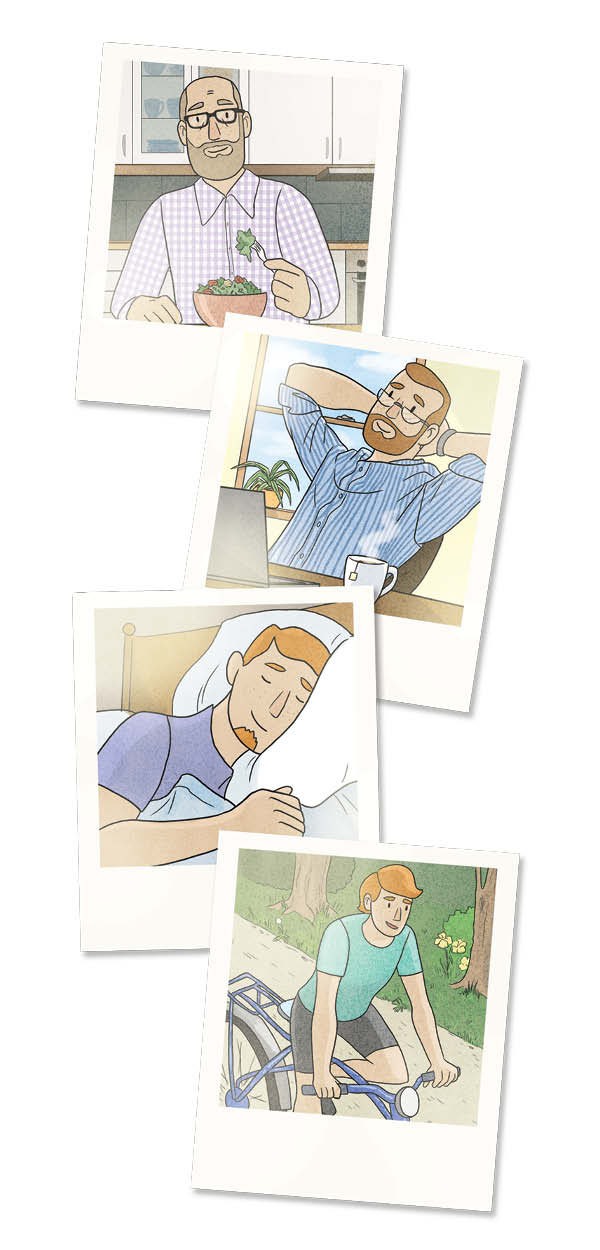

“I always tell people that we know what to do,” Verdin says. “We could gain ten years of life expectancy if everyone would start exercising, eating well, sleeping well, and managing their stress.”

Belsky agrees that such lifestyle changes “are the best prescription for healthy aging that science has today.”

Olshansky concurs, and says that exercise, in particular, is like an “oil, lube, and filter change” for your body and brain, better than any theoretical fountain of youth.

That’s not to say that scientists are not looking for new interventions. Studies of eating patterns, medications, and supplements that might affect the pace of aging are underway.

Among the experimental approaches:

Calorie restriction. Mice and worms put on very low-calorie, nutrient-dense diets have been shown to live longer, healthier lives. But humans are not mice or worms, and studies in people have yet to show longevity benefits, according the National Institute on Aging (NIA).

Fasting (also known as time-restricted eating). Some preliminary studies suggest that people who limit eating to a few hours a day or limit calories on some days each week might get some protection from age-related decline. But the evidence is not strong enough to recommend such practices, the NIA says.

Medication. Several medications appear to extend the lives of animals. One that has shown some promise in humans is an inexpensive, already-available diabetes drug called metformin. A large human trial that will look at whether metformin can delay the onset or slow the course of heart disease, cancer, and dementia in older adults without diabetes is getting underway.

Supplements. No supplement has been proven to slow down aging. That includes resveratrol, a substance found in red wine that some people take in concentrated pill form, despite a lack of safety or effectiveness data. And it includes newer supplements that promise to increase levels of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD), a molecule important to energy metabolism that declines with age. Supplements that increase your NAD levels have not been proven to affect health or longevity.

For now, the best advice, Levine says, is “doing everything your mother told you to do.”

As many people nearing or past their 65th birthdays can attest, you haven’t really experienced the byzantine nature of the nation’s health insurance system until you face signing up for Medicare, the federal insurance program for seniors.

The complexity of a system that contains an alphabet soup of parts may come as no surprise. But the costs of health care in retirement might come as a shock.

“A lot of people think that, once they retire, they are going to go on Medicare and they’ll pay nothing out of pocket,” says Ted Lew, a CAPTRUST vice president and financial advisor based in San Ramon, California.

The truth: Healthcare costs in retirement are significant and should be a major part of your financial planning, Lew and other experts say.

Yet, a survey from the Insured Retirement Institute found that just 25 percent of people aged 56 to 72 in 2019 had factored healthcare costs into their retirement savings plans. The number was a little better, 48 percent, among those consulting with financial advisors.

The number one reason for leaving health care out of planning was the misperception that Medicare would cover everything, the survey found. And the number two reason for lack of planning was uncertainty about how much health care might cost.

How Expensive Is It?

Cost estimates vary. One calculation, from Fidelity Investments, found that a 65-year-old couple retiring in 2020 could, over their lifetimes, expect to pay $295,000 in current dollars for insurance premiums, co-pays, and out-of-pocket expenses, not including non-prescription drugs or most dental services.

HealthView Services put the lifetime bill for the same couple at $387,644 in 2019, with a calculation that included some additional expenses, such as hearing, dental, and vision care. Neither estimate included the costs of long-term care, which can be substantial and are not covered by Medicare.

As of 2019, a private room in a nursing home cost a median of $8,500 a month, and a home health aide cost more than $4,000 a month, according to Genworth, an insurance company.

“People can experience a bit of sticker shock” when they read such numbers, says Matthew Rutledge, a researcher at the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

In a paper published in 2019, Rutledge and a colleague reported that people over age 75 spend an average of 20 percent of their annual incomes on out-of-pocket healthcare costs. They concluded that, while most people can manage those costs, the picture becomes more worrisome when long-term care is included—and when those with the greatest healthcare needs are considered.

Using data that included long-term care, they found that, at ages 75 to 84, the top 10 percent of spenders needed more than half of their incomes for health care; at ages 85 and over, the top 10 percent needed 142 percent of their incomes to cover health costs.

“It gets scary when you are in the top five to ten percent,” Rutledge says.

Of course, no one knows whether they will end up as a big spender, needing years of support after developing dementia, frailty, or other costly problems.

But here’s an important consideration: If you are quite healthy in your mid-life and early retirement years, you are likely to spend more than your unhealthy peers.

“It’s a surprising fact,” Rutledge says. “We tend to think that the unhealthy ones will be the big spenders, but they tend to die sooner, so they don’t spend as much.”

HealthView Services provides this example: A healthy 55-year-old woman can expect to live to age 89, paying $13,165 a year for health care, while a 55-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes can expect to live to age 80, spending $16,635 a year. That nine-year gap in life expectancy means the healthy woman will spend $424,875, while the woman with diabetes spends $266,163.

Such calculations are no reason to give up healthy habits. But they are a reminder that even the healthiest among us need to plan for substantial costs.

The Medicare Decision

Ready or not, at age 65, most people face a decision: whether to sign up for Medicare. Usually, the answer should be yes, says Sarah Murdoch, director of client services at the Medicare Rights Center, a nonprofit advocacy and education group.

That’s because you could face costly penalties and gaps in coverage if you do not sign up when you become eligible for Medicare Part B, the part that covers most routine care and requires premiums, she says. That initial eligibility period spans the three months before and three months after your 65th birthday.

If you are working for and insured by a large employer, you don’t have to sign up for any part of Medicare until you leave your job. That also goes for your covered spouse.

Just about everyone else needs to take action. That includes people without health insurance, but also those with individual policies, retiree coverage, COBRA policies, or coverage from an employer with fewer than 20 workers, Murdoch says. Those policies no longer have to act as your primary insurance once you are eligible for Medicare, meaning they could stop covering your bills.

That’s not all. If you sign up for Medicare Part B late, you pay higher premiums for the rest of your life. You also can expect to wait months for coverage to kick in.

“It is really important for people to know their timelines,” Murdoch says. “We see people making truly innocent mistakes all the time, and it can have sad consequences.”

When you do sign up, you face another choice. Your first option is to stick with traditional Medicare, with its core Part A (hospital) and Part B (doctor and outpatient) coverage. The alternative is Medicare Advantage, coverage from a private insurer that combines Parts A and B, often with additional benefits. Medicare Advantage typically restricts you to a network of providers.

The best choice varies, Lew says. He says some clients go for traditional Medicare because they have doctors who don’t participate in an Advantage plan or because they are retiring in an area with few or no network providers. Others like the one-stop shopping of a network plan.

If you do choose traditional Medicare, be sure to add a supplemental Medigap plan. That’s because traditional Medicare puts no cap on out-of-pocket costs, but all supplemental policies do.

Ted Lew, Financial Advisor

But buyer beware: While your mailbox may overflow with pitches from supplemental insurers, you can get better information at medicare.gov, Lew says.

Tailoring a Plan for You

When Doug and Teresa Wright started retirement planning a few years ago, the couple realized they would face some new costs when Doug left his job that provided health insurance for both of them. They would have to pay Medicare premiums for Doug and buy individual coverage for Teresa, who is a decade younger.

“When I worked, I didn’t pay anything,” says Doug, 65, now retired from his job as vice president of a Silicon Valley manufacturing company. The couple now pays about $1,000 a month just for premiums, mostly for Teresa, “but we planned for that,” Teresa says.

Planning for such individual circumstances is crucial, Lew says. How much you need for health costs can vary widely, depending on factors ranging from your health history to where you plan to live. For example, if you live outside the country, you won’t be able to use Medicare while abroad.

How you save for retirement healthcare expenses can also vary. One increasingly popular choice is to fund a health savings account (HSA) while you are still working. The accounts are not available to everyone—you can only contribute if you are enrolled in a high-deductible health insurance plan. But, if you are eligible, it’s smart to open an HSA as soon as possible, Lew says, because the accounts “have a triple tax advantage.” Contributions, earnings, and withdrawals for eligible health expenses are all tax-free.

Many people also consider buying long-term care insurance, but that can be a difficult decision, Lew says. Generous, affordable policies available years ago turned out to be a bad deal for insurers, who “lost their shirts,” he says. As a result, “the current policies tend to be very pricey,” but some people will find them worthwhile, he says.

An alternative is to set apart some money as a self-insurance pot for long-term care, says Lew.

In the end, he says, health isn’t just one more thing to consider in your retirement planning—it may be the most important thing.

“If you don’t have your health,” he says, “nothing else really matters.”

Ready for Medicare?

If so, you need to know your ABCs and D—the major parts of the government health insurance plan for people over age 65 (and for some younger disabled people).

PART A | Hospital Coverage

This covers hospital stays, hospice care, and some short-term skilled nursing care—such as when you need a rehabilitation center after you’ve been hospitalized for an illness or injury.

Most people don’t pay premiums for Part A because they’ve already paid for it through payroll taxes. But you still pay deductibles and co-pays for certain services. The 2020 deductible for a hospital stay is a hefty $1,408. Many people buy supplemental Medigap policies to help cover such costs.

PART B | Doctor and Outpatient Services

This covers doctors’ bills, outpatient lab tests, preventative services, mental health visits, ambulance transport, and some medical supplies.

You pay a premium for Part B. The 2020 rate is $144.60 for people with individual annual incomes up to $87,000. Those with higher incomes pay more—as much as $491.60. There’s also a modest annual deductible and a 20 percent co-pay for many services.

PART C | Medicare Advantage

This is not really a third part of Medicare. It’s private insurance that covers everything in Medicare’s Parts A and B. These plans often cover services, such as routine vision, hearing, and dental care and fold in prescription drug coverage. You may pay an added premium on top of your Part B premium.

These plans are generally run by health maintenance organizations (HMOs) or preferred provider organizations (PPOs) that restrict you to network providers. Costs and coverage vary. Some rural areas have no Medicare Advantage providers; some urban areas have dozens.

PART D | Prescription Drug Coverage

You buy this coverage through a private insurer, as part of a Medicare Advantage plan or in addition to traditional Medicare Parts A and B.

These plans generally come with premiums and other out-of-pocket costs, which can include deductibles and co-pays. Different plans cover different medications, so it’s crucial to check their drug lists—called formularies—through medicare.gov for any medications you take regularly. This coverage can be invaluable given the high prices of many medications.

To Learn More: In addition to medicare.gov, you can get free counseling from the Medicare Rights Center at 800.333.4114. The center also offers Medicare Interactive, a free online reference tool for consumers, and Medicare Interactive Pro, paid online courses for professionals.