-

Solutions

- Solutions

- Individuals

-

Retirement Plan Sponsors

- Retirement Plan Sponsors

- Corporations

- Educational Institutions

- Healthcare Organizations

- Nonprofits

- Government Entities

- Endowments & Foundations

- See All Solutions

Comprehensive wealth planning and investment advice, tailored to your unique needs and goals.Investment advisory and co-fiduciary services that help you deliver more effective total retirement solutions.CAPTRUST provides investment, fiduciary, and risk management services for nonprofit organizations. -

About Us

- About Us

- Our People

- Our Story

- Learn About CAPTRUST

-

Locations

-

Resources

- Resources

- Articles

- Podcasts

- Videos

- Webinars

- See All Resources

Fulkerson says her fellow attendees were much like the older adults she regularly counsels on encore careers. “These were very energized people trying to figure out what to do next with their lives.”

There are a lot of gray heads in online and brick-and-mortar classrooms these days, and a lot of adults over the age of 50 are asking the same question: What’s next?

Some are seeking new career skills. Many others are pursuing learning for learning’s sake—for intellectual stimulation, a sense of purpose, and, often, social connection.

And educators are responding by throwing out the welcome mat for mature learners in a bigger way than ever before. There are courses online, including the massive open online courses (MOOCs) that some major universities now offer to anyone with an internet connection. There are also plenty of traditional classrooms in colleges, universities, community centers, and elsewhere that welcome older learners.

Want to get a master’s or doctoral degree decades after you last set foot on a campus? Some universities now have support services just for you. Maybe you want to study the history or literature you missed as an undergrad focused on other things. You can find a no-pressure class for that. Or maybe you want to polish your tech skills, prepare for a new leadership role, or unleash your inner entrepreneur. Opportunities abound—in everything from on-campus fellowships to online micro-credential courses.

Still, “We have so much mind-shifting to do,” says Nancy Morrow-Howell, a professor of social policy who directs the Harvey A. Friedman Center for Aging at Washington University in St. Louis. “When we created all our educational institutions, life expectancy was half as long. Now that we live much longer, we can’t stop our formal education at age 22.”

While not all later learning is career-focused, economic forces are driving the change. “We want to work longer, and the workforce needs us longer,” says Morrow-Howell. “But the shift to multigenerational learning is just getting started.”

University for Life

At age 57, Lynne Johnson, of Dallas, Texas, is a proud recent graduate of Washington University’s master’s degree program in social work. She hopes her degree will help her find a job with an organization that assists older adults and their caregivers.

She started her graduate studies at the university’s Brown School in 2015, a couple years after completing a long-delayed bachelor’s degree at another university. In between degrees, she was the primary caregiver for her mother, who has since passed away. Previously, she had a long career in film production and a shorter stint as an English teacher in Taiwan.

Despite her many life experiences and her clear career goals, Johnson says she did not feel entirely welcome when she showed up at graduate school in her early 50s. “I could tell early on—even in the orientation—that the younger students didn’t want anything to do with the older students,” she says. “It was very awkward, and I had a hard time making friends and fitting in.” Some faculty members were unwelcoming as well, she says.

Eventually, she gained confidence and felt more at home, Johnson says. But she saw a need for more support for students like herself. In fall of 2018, shortly after her graduation, she worked with Morrow-Howell to launch a group for students entering the Brown School at age 30 and over. The student group is part of a support program called Next Move.

The university, like many others, is taking broader steps to nurture learners of all ages. In late 2018, it joined the Age-Friendly University Global Network, a group that includes more than 50 universities in the U.S., Canada, Europe, and Asia.

The network is focused, Morrow-Howell says, on helping universities figure out ways to serve people of all ages and promote multigenerational connections.

“Older and younger students will figure out that they are all just people,” she says. “That could go a long way toward reducing ageism—by the young and old, toward the young and old, in workplaces and elsewhere.”

It’s no coincidence that universities are making these changes as alumni and other older adults, including retirees who move to university towns, are asking for more ways to partake in university life, says Holden Thorp, a former Washington University professor of chemistry and medicine, who was the university’s provost and executive vice chancellor for academic affairs for four years. Thorp is now editor-in-chief of the Science family of journals.

“We are definitely seeing some folks wanting to put together their encore careers, but we also are seeing folks who realize that maybe they could have gotten more out of college the first go-around, and they are coming back to do some of the things they wish they had done,” he says.

Traditional college students in their teens and early 20s “do not always think about how rich the intellectual experience in front of them can be,” says Thorp. “But if we can plant the seeds and they come back 30 years later, we’ve done our job.”

Learning for Learning’s Sake

While career and degree-granting programs are welcoming more older learners, some of the most popular courses for mature adults remain those that offer learning for learning’s sake—with no grades or other expectations attached.

That’s the niche served by the Osher Lifelong Learning Institutes, a network of 124 programs hosted by colleges and universities serving 390 towns and cities in all 50 states, says Steve Thaxton, executive director of Osher’s national resource center at Northwestern University, Chicago. He notes that several hundred additional lifelong learning programs, unaffiliated with Osher, operate in other communities. A comprehensive list can be found at osher.net.

While each institute chooses its own offerings, the most popular courses nationwide fall into a few consistent categories year after year, Thaxton says. The list includes history, fine and creative arts, current affairs, literature, religion, philosophy, spirituality, and health and wellness.

The institutes, launched in 2001, “have grown and grown,” Thaxton says. They now serve about 200,000 members nationwide.

One of the largest programs is at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. The greatest challenge for the program is finding enough classroom space, across four counties, for all the courses attended by its 2,600 members, says Institute Director Chris McLeod. For some popular classes, “we practically have to shoo people out of the classroom, because if we don’t, there will be gridlock in the parking lot” when students arrive for the next session, she says.

McLeod is seeking a new central classroom facility. At the same time, her institute and others like it are weighing the pros and cons of online access to some classes. Such access could expand participation but could also limit the social opportunities that are an important part of the experience, McLeod says. A happy medium might be to set up satellite classrooms—at assisted living centers, for example—where rooms full of people could interact with one another and with an instructor and students in another locale.

In a world where many people want to keep learning longer than they can keep driving, those kinds of accommodations make sense, Thaxton says.

McLeod says there’s also a demand for “more classes around rethinking and reimagining retirement because of longer life spans.” In fact, one of those classes was taught this fall by Fulkerson, the psychologist and career counselor studying online marketing to expand her own options.

According to Fulkerson, “there is a huge unmet need” for helping people past traditional retirement age realize and achieve their full potential. That’s why lifelong learning, for credit or not, for credentials or not, is a growth industry.McLeod agrees. Her members, she says, are “some of the most energetic, highly educated people I’ve met in my life, and they are saying, ‘I’m not done.’”

These stories—based on findings from a study performed by money manager United Income—claim that only 4 percent of retirees are making the financially optimal decision to wait until age 70 to begin receiving benefits. And, while delaying until 70 seems like a stretch, most would benefit by waiting at least until age 65.

As a result of their choices, “they will miss out on a collective $3.4 trillion in benefits before they die,” according to a Bloomberg article on the topic.

That’s a lot of money being left on the table. So much that you must ask yourself: Why is this happening?

As you would expect, that question has many potential answers—some practical and some more esoteric.

Practical Explanations

Practically speaking, there are many partial answers. For example, some of these retirees may not have had access to good software, tools, or advice to help them make this important decision, so they made the only one that made sense to them.

According to Federal Reserve data, the median and most common retirement age in the United States is 62. You know what else it is? It’s also the minimum age at which you can start collecting Social Security benefits.

Arguably, the reduced benefit available at the early eligibility age of 62 is a financial incentive to file. In other words, getting something today—even at a reduced rate—is better than what I could have received yesterday.

This urgency has been fueled by Social Security staffers who have inappropriately told people who make benefit inquiries to “Take your benefits because you could die tomorrow,” says Laurence Kotlikoff, professor of economics at Boston University and author of Get What’s Yours: The Secrets to Maxing Out Your Social Security.

And, of course, with the negative press we periodically see about benefit cuts or the solvency of the Social Security trust fund, it is understandable that some fraction of filers may want to tap into their benefits early to make sure they get out what they put in—even if they aren’t optimizing.

No doubt there is a kernel of truth in these explanations, but that doesn’t explain the overwhelming miscalculation that Social Security filers repeatedly make.

The fact is: There are several aspects of the Social Security filing decision that simply confound the human brain. These behavioral biases, as they are known, can render humans unable to make optimal—or sometimes even OK—decisions about their financial lives. Arguably, there could be numerous biases negatively influencing the Social Security filing decision, but let’s focus on two.

Immediate Gratification

The first of these biases is called present bias. Present bias is the idea that an individual will place greater value on something received in the present moment, rather than waiting to receive it in the future. It suggests that, given the choice between a payoff today and a payoff in the future, we tend to choose the payoff now—otherwise known as immediate gratification. This is true even for decisions that our future selves may regret.

In a nutshell, we see the future self we are delaying gratification for as a separate person from our current self, making the decision in question a choice between doing something for ourselves today or doing something for a stranger tomorrow.

In the case of Social Security, present bias causes millions of Americans to value—and therefore file to receive—benefits today versus benefits later, despite the significantly higher payouts they’d receive if they waited. Of course, present bias is not limited to the Social Security decision. It is—pardon the expression—ever present in our lives.

Present bias is why we splurge on a big vacation or a lavish purchase today and fail to start saving. It’s why we claim we’ll save more later, after we get a raise or bonus, but don’t. It’s why we eagerly commit to dieting or a new exercise regime—so long as we get to start it tomorrow.

We see the certain and immediate costs to these choices and weigh them against murky benefits in the distant future. Immediate gratification wins almost every time.

Fuzzy Math

The other behavioral bias worth mentioning is called exponential-growth bias. Exponential-growth bias is the tendency to undervalue the effects of compound interest, leading to the underestimation of future values. Because we are very bad at these calculations, our underestimation can be massive.

Victor Stango and Jonathan Zinman from Dartmouth College wrote about exponential-growth bias in their 2007 paper, “Fuzzy Math in Household Finance: A Practical Guide.” They point out that exponential-growth bias is relevant to household finances in two ways. Unchecked, exponential-growth bias means that people will get the future value of savings or investments wrong, especially “when the opportunities are relatively long-term and/or high-yielding,” say Stango and Zinman. “They underestimate returns because they underestimate how quickly interest compounds.”

Exponential-growth bias also leads to underestimation of interest costs on borrowing. “This problem is the mirror image of understanding compound interest,” say Stango and Zinman. The net result is that households with a strong exponential-growth bias tend to save less and borrow more—a double-edged sword of bad financial behaviors.

Back to Social Security. Exponential-growth bias is part of why filers are more likely to file for benefits before full retirement age. It causes them to undervalue the benefits of waiting. Further, because many people are cash poor, “they can’t wait until age 70 to collect their retirement benefit when they’d be roughly 70 percent higher, after inflation, than if they started claiming at age 62,” says Social Security expert Laurence Kotlikoff. They can’t grasp the real value of waiting.

The fuzzy math challenge of Social Security is further complicated by the fact that Social Security pays an inflation-adjusted income until you die—and most filers are not capable of valuing the longevity insurance and inflation protection that’s built into benefits. But that’s a story for another day.

Of course, all is not lost. You can, in fact, overcome the challenges of our flawed human wiring when it comes to maximizing Social Security benefits. What can you do?

Here are a few suggestions:

- Estimate your benefits. Through the Social Security Administration’s website at ssa.gov, you can get a personal benefit statement that takes into account your earnings over the years. From there you can model the impact of taking benefits before and after your full retirement age—and clearly see the value of waiting.

- Plan to maximize benefits. Not everyone can afford to delay taking benefits until age 70. A comprehensive retirement plan that looks at your expected retirement spending and potential sources of income can help you understand if it’s possible to delay or when you’ll need to start taking Social Security benefits.

- Shock test your plan. As the saying goes, “No plan survives contact with the enemy.” Make sure your plan includes extreme scenarios, including living to 100 (or older!), a significant market sell-off the year you retire, a Social Security benefit cut, and a sustained increase in spending—whatever you need to test to make sure you’re going to sleep at night.

- Reserve the right to reassess. Retirement is not a set-it-and-forget-it endeavor. It’s an iterative process. Update your plan periodically—every three to five years or whenever you’ve experienced a significant change—and be prepared to adapt. Sustained good or bad markets, a sudden change of health status, or sale of property are all excellent reasons to loop back and reassess your plan.

If you’re reading this, chances are good you have already taken at least one big step and hired a financial advisor. A financial advisor will take the time to understand your individual situation and create a retirement plan and investment strategy tailored to your specific needs, goals, and risk tolerance. As importantly, an advisor can help you keep your emotions and biases in check so that you stay on course.

Erikson says the drive to contribute to another’s positive development using the knowledge and wisdom you’ve accumulated over the years leads to successful completion of the generativity stage and the later “integrity” stage of life in later adulthood, when you look back and review your contributions. His research shows that those who don’t reach out to others and give back risk feeling disconnected and may regret missed opportunities.

One way we can leave a lasting legacy is by mentoring others. Mentoring can occur in all types of environments—anytime and anywhere. Aside from the seminal task of parenting, workplace mentoring can help fulfill Erikson’s generativity task during middle adulthood. Workplace mentoring programs may sustain and improve companies, in part, by powerful effects on both mentor and mentee. For those in retirement, post-career mentoring can lead you in new directions for a more satisfying next chapter.

The Power of Workplace Mentoring

Companies are eager to transmit knowledge from experienced workers to new hires. By teaching young employees about the successes and failures that they have experienced, mentors play a vital role in the making of future leaders. Most C-suite executives—75 percent—say that mentoring helped to propel them to leadership positions.1

Mentoring has many other positive attributes that impact the bottom line. Studies show that mentoring programs help companies recruit quality candidates, increase employee engagement, and boost job retention. When an employee has a mentor, he or she is less likely to be looking at other job options.

Mentoring programs also help increase diversity. Research shows that when managers are paired with mentees of a different race or gender, getting to know the person helps break down stereotypes or bias; the mentor becomes a champion of the mentee through the new relationship.

Those are several good reasons that more than 70 percent of Fortune 500 companies have some variation of a mentoring program, and about 25 percent of small companies do, too.2

Experts say there’s no one best mentoring program; the goals of the company, the culture, and even new technologies, all help shape different types of mentoring approaches.

Essential Advice for Mentors

Top corporate mentoring programs don’t get that way by accident; sponsoring companies evaluate their programs and listen to feedback. First Round, a venture capital firm that creates initial stage funding of tech companies, issued a call for mentees and mentors and received an overwhelming response from both.

The company structured its mentoring approach so that each mentor-mentee pair met every other week for one quarter. The mentees developed an agenda and shared it prior to their meetings, and First Round surveyed how mentees were applying their learning—all good workplace mentoring practices.

First Round then evaluated 100 matches to find what qualities make the most successful mentor-mentee matches and distilled the knowledge into a piece titled “We Studied 100 Mentor-Mentee Matches—Here’s What Makes Mentorship Work.” Here is what they found:

- It’s not just business. Successful mentor-mentee pairs use their time together to form personal connections. Find out who each other is outside of work. Ask about favorite activities, hopes and dreams, and family. This forms the beginnings of real relationships.

- Transparency and self-disclosure. A seminal piece of advice for mentors is to be transparent. When you share a story about a time a project didn’t work out the way you planned or something you regret and why, you’re showing vulnerability. Your mentee is more likely to feel that he or she can bring a problem to you without fear of criticism.

- The ability to listen. Good mentors are also good listeners. Meet in a conference room or nearby coffee shop for more privacy. Mute your phone, and pay attention.

Think about the people in your orbit. To whom have you gone for advice? Most likely, it’s the people who sat back and listened without judgment—who didn’t jump in immediately with all the answers or counterpoints. A poetic essay by Brenda Ueland, “Tell Me More: On the Fine Art of Listening,” points out that simply being able to talk out a problem can help clarify what needs to happen next. Being heard is an important gift you can give your mentee.

Benefits for Both of You

Mentoring not only aids the mentee’s growth and development, it also provides important benefits for the mentor. If your mentee is younger and recently out of school, he or she may show you the latest technology or reveal new practices in your industry.

Mentoring also has the potential to develop leadership skills. A Sun Microsystems study of employee career progress found that those who mentored others were six times more likely to be promoted than employees who didn’t mentor.3

Mentoring also has powerful psychological benefits, both in the workplace and otherwise. When mentoring, you’re giving of yourself to others and the act has a boomerang effect. When you help guide someone’s growth and development, you gain a sense of fulfillment, purpose, and achievement. Research shows that helping others can cause physiological changes in your brain related to feelings of happiness, followed by a sense of well-being, and may stimulate neurochemicals involved in experiencing a reward.

Beyond the Workplace

If you’re approaching retirement, have you thought about life after you’re no longer in the 9-to-5 world? Experts say it’s important to have a plan. Going from operating on all cylinders to a full stop can lead you to question your purpose. Retirement offers tremendous freedom to make a truly meaningful impact in the lives of others.

You don’t need to be a professional expert to be a great mentor. You just need to be able to answer basic questions or know where to find the answers.

There are a multitude of different mentoring opportunities around each and every one of us. For example, if you relate to children well, you could be a welcome addition to a mentoring program helping at-risk youth. In fact, analyses of programs mentoring at-risk youth show that children who have a consistent relationship with a mentor are 52 percent less likely than their peers to skip a day of school and 37 percent less likely to skip a class.4

Another option, faith-based mentoring, is very common. Also known as spiritual mentoring, it is largely about modeling a mature life built on the values of your faith and being there for the mentee when questions arise.

Athletic coaches are in an advantageous position to become mentors. A few minutes during a water break or a quick walk-up to the athlete while heading to the locker room can bring about surprising results. Players become comfortable around coaches and learn to initiate such mentoring moments on their own.

The bottom line is, mentoring opportunities are everywhere. If you’re knowledgeable about things like budgeting from paycheck to paycheck, obtaining employment or improving employment situations, improving your level of education, improving homemaking skills, or establishing a network of people who are reliable, you have plenty of valuable insight that you could pass on to another person through mentoring.

To quote the website of Trusted Mentor, a nonprofit organization in Indianapolis, Indiana, “Whether you are a business professional or formerly homeless, your knowledge and life experiences can help one of our mentees make the positive changes they desire for a more successful future.”

If you want to help an individual who is seeking to be supported by a mentor, you can visit mentoring.org and search the Mentoring Connector database for a variety of programs in your community and connect with them directly about becoming a mentor.

Mentoring can make a lasting difference in someone else’s life. What do you want your legacy to be? Mentoring may play a central role.

1 George, Phil, “Your Next Must-Have Job Benefit: A Mentoring Program,” Recruiter, 2017

2 Jones, Mel, “Why Can’t Companies Get Mentorship Programs Right?” The Atlantic, 2017

3 Richards, Kelli, “The 4 Most Important Reasons You Need to Become a Mentor,” Inc., 2014

4 “Mentoring impact,” Mentor: The National Mentoring Partnership, 2019

In today’s tight labor market, retirement plan sponsors across industries are battling it out for recruitment value, retention of current employees, and a general sense of goodwill among current retirement plan participants.

So how can plan sponsors know if their plans are headed into this competition with a leg up or in need of improvement?

According to James “Jan” Harper, senior vice president and chief human resources officer at Tidelands Health, it’s about setting goals, measuring against those goals, and making that process a habit.

Take Your Plan’s Pulse

Measuring a plan will open plan sponsor’s eyes to a wealth of data that can be used to assess a plan’s health. Metrics like plan utilization, average contribution rate, and diversification of investments within retirement accounts are invaluable inputs for plan providers looking to maximize the value derived from their offerings.

Useful measurements that detail the current state of its plans give Tidelands Health clues on where to focus attention when looking to boost plan performance, according to Harper. Success metrics, such as participation rate, contribution rate, and diversification of account assets are “provided [by our recordkeeper] on a quarterly basis at a minimum,” says Harper.

A metric Harper takes very seriously—and perhaps the most popular metric to gauge plan success—is participation rate. A plan’s participation rate is a good measure of the percentage of their workforce that is actively saving for retirement.

Plan sponsors can calculate participation rate by dividing the number of employees making payroll deduction contributions to the plan by the number of employees eligible to contribute. For example, if an employer has 1,000 eligible employees and 700 are making contributions to the plan, the plan’s participation rate is 70 percent.

Contribution rate can help employers measure plan effectiveness in a different way. By tracking the percentage of income employees dedicate to their retirement plans, plan sponsors can generally measure whether or not their employees are saving enough for their retirement.

Diversification of account assets measures how participant balances are distributed among investment asset classes, such as stocks, bonds, and cash equivalents. This is another important measure because it helps sponsors gauge participants’ general level of investment savvy and how likely they are to react to inevitable market swings.

Looking at Success Ratios

While all of these metrics provide a baseline indication of how well a plan is performing, none of them capture the big-picture view most plan sponsors are trying to see: what percentage of plan participants are on track to meet the suggested income replacement ratio in retirement. This is perhaps the single most insightful piece of data available to plan sponsors.

This calculation takes each participant’s current balance, age, savings rate, assumed rate of return, and retirement age, and projects an account balance at normal retirement age (commonly 65). More complex calculations add the ability for participants to include other retirement assets and retirement income streams.

The calculation then projects the retirement income stream that the account would generate given a set of assumptions, adds in expected Social Security benefits, and provides the result as a percentage of pre-retirement income replaced in retirement. In many cases, like that of Tidelands Health, retirement income replacement ratio calculations are completed by the plan’s recordkeeper.

“Plan sponsors can take this information and compare it with a plan-level goal that represents the income necessary to maintain the same standard of living in retirement as enjoyed while working, typically between 70 percent and 80 percent of an individual’s final year’s salary,” says CAPTRUST Defined Contribution Practice Leader Scott Matheson.

However, Matheson explains that there are a number of challenges in determining the exact percentage of participants who are on track for meeting their retirement income replacement savings goals. “Because replacement income comes from Social Security, the current retirement plan, retirement plans from previous employers, and other savings, plan sponsors cannot capture all potential replacement income for every participant,” he says.

If a recordkeeper does not have all the necessary data to complete the calculation, the plan sponsor can provide a file with the census information to the recordkeeper to generate the projections.

“Because of the unpredictability of financial markets, a recordkeeper should run multiple iterations of these projections,” says Matheson. “Different investment return scenarios, using tools like Monte Carlo simulations, provide a range of potential outcomes for each participant.”

What if plan sponsors aren’t happy with what they find? The metrics provide a GPS to direct their attention and budgets.

Plan sponsors concerned about plan participation rate should consider implementing automatic enrollment. If low plan contribution rates are an area of concern, roll out a new automatic annual increase program.

Or get creative like Tidelands Health. According to Harper, as part of Tidelands Health’s Wellness Program, participants are required, as a free benefit, to contact an appointed financial counselor and complete a retirement needs assessment on a biannual basis. Harper explains that participants in the health plans who fail to do so will forgo up to $1,000 in credits that would otherwise be available to the participant to pay out-of-pocket healthcare expenses such as deductibles, copays, co-insurance, etc.

A Checkup from the Neck Up

How employees feel about their retirement readiness and the benefits offered to them matters, and knowing what employees want can go a long way toward creating an outstanding compensation and benefits package—a tool that can both attract and retain workers.

A full three-quarters of Americans are only “somewhat confident” or are “not confident at all” that they will be financially prepared for retirement, according to a recent PLANSPONSOR article. And, according to U.S. News & World Report, few employers evaluate employee satisfaction with their retirement benefits. Only 34 percent of plan sponsors have conducted an employee survey to gauge how satisfied employees are with the education and support they receive about their retirement plan.

So, what can plan sponsors do to better understand how participants feel about their retirement readiness?

Ask them.

Ask them if they are happy with the benefits. Ask them if they are making use of them, or if they need some additional perks to sweeten the deal. Ask them how confident they feel about their financial preparedness for retirement. Ask them what’s working and what’s not working about the plan offering.

This type of qualitative research approach allows plan sponsors to gain a deeper grasp of the challenges retirees face every day. This data is observed and recorded through the methods of observation, one-to-one interviews, focus groups, and surveys.

A 360-degree survey administered by a third-party vendor can be useful for gauging employee satisfaction with the benefits package and for gathering general feedback. However, it is also possible to use a low-cost survey resource, such as Survey Monkey, to develop a quick and easy retirement confidence survey for employees.

What’s important is not how plan sponsors obtain this essential participant data, but that it is collected and interpreted in a way that can help elevate the benefits offering. Of course, if you’re going to ask the questions, you should also be prepared to act on at least some of the feedback.

Set Your Target

Metrics gleaned from an employee survey are helpful by themselves. They provide plan sponsors with a baseline against which they can measure progress or identify trends—positive or negative. But what do good or bad metrics look like for a particular employee population, industry, or plan design? What are the right targets to shoot for?

Setting the right goals or benchmarks doesn’t have to be guesswork. Once data on the plan’s leading indicators, outcomes, and qualitative measures has been gathered, plan sponsors can compare the plan to plans of similar sizes across their industries on a regular basis.

“This is an area where plan sponsors should lean on their recordkeepers or advisors to give them broad-based industry conventions or benchmarks,” says Matheson. “You can work with them to find out what your competitors’ plans look like based on the metrics that matter to you and the subject matter experts you surround yourself with.”

Tidelands Health sets goals based on what they are hearing and seeing from their industry peers, according to Harper. “When I have the ability to sit among my contemporaries in a national audience, and I hear that the organizations I respect say that their participation rates are 90 percent, I set my sights on a 90 percent participation rate for our plans,” he says.

Many plans determine metric goals based on information provided through the Plan Sponsor Council of America (PSCA), a nonprofit association that provides services, best practice information, and advocacy to defined contribution plan sponsors. The PSCA’s 61st Annual Survey of Profit Sharing and 401(k) Plans reports on the 2018 plan-year experience of more than 500 plans.

Another great reference when setting plan goals is asset manager Vanguard’s How America Saves 2019. Here, you will find data on more than 1,900 defined contribution retirement plans and more than 5 million participants. In this 18th edition of How America Saves, Vanguard updates its analysis of defined contribution plans and participant behavior based on 2018 recordkeeping data. Specifically, plan sponsors will find retirement plan benchmarks and data supplements such as average participation rates, median account balances, typical asset allocations, and much more.

These reports serve as valuable reference tools that will prove very useful as plan sponsors look to measure and benchmark their plans.

Some plan sponsors, like Tidelands Health, utilize services offered by a recordkeeper to get an idea of current plan success ratios. Recordkeepers have access to information on how well—or how poorly—participants within other plans are prepared for post-retirement income needs. According to Matheson, obtaining and interpreting this information is critical to setting appropriate success factor goals for your plan.

In addition to setting quantitative goals, plan sponsors are also setting qualitative goals. “A good starting point for setting goals around qualitative targets is the Employee Job Satisfaction and Engagement research report developed by the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM),” says Matheson. The report covers qualitative benchmarks for stacking up against a retirement plan, such as percentage of employees satisfied with their benefits, how employees rank importance and satisfaction with benefit aspects, what kinds of benefits retain employees, plus loads more research conducted by SHRM.

Measuring Is Not One and Done

Determining the frequency, scope, and specific metrics of these checkups is essential. Gathering plan metrics on a regular basis provides plan sponsors with a way to see how their retirement plans stack up against others within their industry so they can focus their attention on plan design tweaks, promotion opportunities, or employee groups who are failing to take advantage of this important benefit.

Getting started is what’s important. Plan sponsors should understand that their methods and measuring criteria can—and should—evolve over time as plans and goals change. For plan sponsors just beginning this journey, focusing on baseline metrics like participation rate, contribution rate, and diversification of account assets provides a solid step in the right direction. Over time, they may want to consider exploring different areas of measurement to identify new opportunities for improvement or uncover positive and negative trends.Having an effective retirement savings program can come with real rewards for institutions that are able to stay on the right side of metrics that support their goals. While each case is different, there is no doubt that measuring gives plan sponsors key information in making their retirement benefits as competitive as possible.

The millennial generation is now the country’s largest, comprising one in three American adults. In the next decade, it could also become one of the richest, as millennials begin to inherit more than $68 trillion from their baby boomer parents. This marks the largest generational transfer wealth in history.

For nonprofits, millennials represent a tremendous opportunity. And organizations that do the work now to understand this demographic group may be able to better engage them as lifelong partners and donors. In this article, we’ll explore some key characteristics of millennial donors and how nonprofits might shift engagement strategies to reach this unique group.

Let Them Get Their Hands Dirty

At this stage of their lives, millennials are more likely than other generations to donate time instead of money. With lower pay and more student debt than previous generations, millennials are more likely to report limited disposable income.

“They’re dealing with a lot of competing financial priorities, but that doesn’t mean they don’t want to help,” says CAPTRUST Director of the Institutional Portfolios Practice Grant Verhaeghe. “Creating a sense of ownership for millennials around a fundraising activity can be the first building block of an ongoing relationship.”

One positive experience can create a lifelong connection. Therefore, nonprofits might consider offering in-person or virtual fundraising events to help donors feel more deeply connected to their organizations. Charitable races, exercise classes, community improvement days, litter pick-ups, and food- or drink tasting events are a few common examples.

“Millennials tend to enjoy hands-on volunteer experiences, participating in events that allow them simultaneously to give time and raise money in support of their favorite causes,” says Verhaeghe.

One well-known example of an experience-based fundraising challenge was the 2014 water-bucket challenge that raised money for the ALS Association. As part of the challenge, more than 17 million people, including Bill Gates and former President George W. Bush, dumped ice-cold water over themselves. The ALS Ice Bucket Challenge raised $115 million—twice as much as the charity raises in a typical year.

However, raising a windfall that’s equal to double your organization’s annual budget, like the ALS Association did, can present its own unique challenges. For instance, the ALS Association reported running a significant deficit five years after, as they spent down the burst of money from the Ice Bucket Challenge.

The Ice Bucket Challenge also tapped into millennial social media use. Promoted solely through social media platforms, the challenge went viral, with more than 17 million people posting videos online.

Be Tech Savvy

Although Gen Z may give them a run for the money, millennials are still one of the biggest consumer groups of social media. According to The Millennial Impact, 90 percent of millennials use one or more forms of social media daily, and 51 percent use it to engage in causes they care about. This generation also likes to use an array of digital platforms to reach out to their personal networks and ask for help in fundraising. This includes Facebook, Quora, Twitter, Instagram, and LinkedIn, to name just a few.

“By engaging millennials online and through digital media platforms, nonprofits can connect with a much larger network,” says Eric Bailey, a CAPTRUST financial advisor specializing in institutional fiduciary services for endowments and foundations. “This generation uses social media to amplify their voices on issues that matter to them, and nonprofits should be taking full advantage of that.”

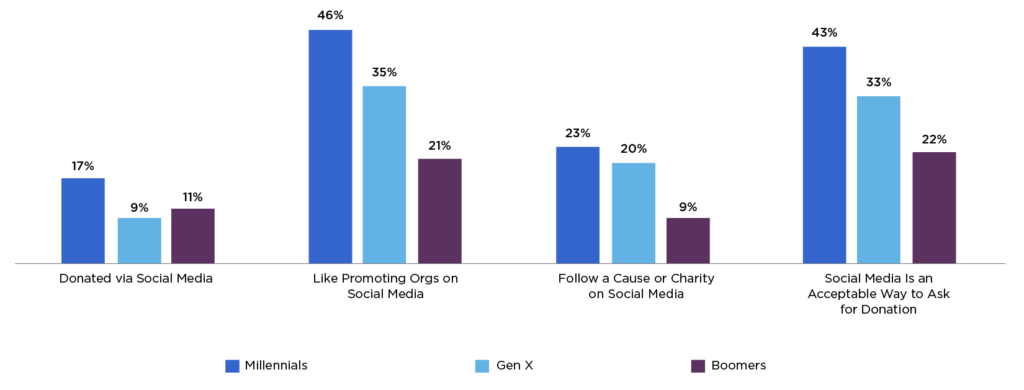

As Figure One shows, almost half of millennials who have given charitably enjoy promoting nonprofit organizations through their social media accounts. Additionally, millennials are twice as likely as baby boomers to follow a cause or charity on social media. And they’re nearly twice as likely to see social media platforms as an acceptable way to ask for donations.

Figure One: Social Media Donor Engagement by Generation

Source: “The Next Generation of American Giving,” Blackbaud Institute, 2018

Peer-to-peer fundraising is another popular technology used by many nonprofit organizations. “It’s a great way to attract new donors and reach new networks of people,” says Bailey. This method of fundraising is a multitiered approach through which individual fundraisers set up a personal fundraising page to accept donations, which are then received by your nonprofit.

“[Individual fundraisers] essentially have their own websites,” says Brad Davis, executive director at the WakeMed Foundation, which uses peer-to-peer fundraising throughout the year. “We give them sort of a template and some boilerplate stuff, and then they personalize it.”

This strategy makes use of a donors’ existing social network, encouraging supporters to collect donations from their peers, friends, coworkers, family members, and neighbors on behalf of the nonprofit. “Peer-to-peer campaigns are effective because they build on relationships, make use of your existing donor base to reach new audiences, and help build social proof,” says Bailey. “Nonprofits absolutely need to use digital platforms to make connections with millennials and to clearly communicate their mission and needs,” says Bailey. “But that’s certainly not the only way to meaningfully connect with millennials. We’re also finding that millennials are active participants in corporate giving programs.”

Get Them Where They Work

Of working charitable givers, more millennials than any other generation are interested in workplace giving, and 40 percent have already participated in a workplace fundraiser, according to the Blackbaud Institute. These facts speak to an emerging opportunity for nonprofits to reach present and future donors where they are.

Workplace donations dramatically reduce administrative costs for charities. And automatic payroll deductions are one of the few opportunities for your organization to secure an ongoing, predictable source of revenue. In fact, almost half of survey respondents identified workplace giving as a major growth strategy for their organization, according to Nonprofits Source.

Davis says charitable payroll deductions have been a successful strategy for the WakeMed Foundation in Raleigh, North Carolina. “We raised about $800,000 last year from WakeMed employees at all levels, and they pay through payroll deductions, which is really cool,” he says.

However, according to Bailey, the options for employee giving may be limited to a preset list that would vary by company. The challenge for each nonprofit is figuring out how to be included on those lists of eligible charities.

Nonprofits can get started by joining one or all the organizations that set up payroll deduction giving campaigns at corporations. Some of these organizations are America’s Charities, EarthShare, and Community Shares USA.

Many corporations also offer paid time off for employees to volunteer, offering yet another means for nonprofits to connect with millennial givers. Bailey recommends nonprofits reach out to individual corporations’ human resources departments to explore partnership opportunities.

Of course, there are a variety of ways nonprofits can team up with corporations to effectively structure an employee volunteer program, including day-of-service events, skills giving, and pro bono services. But organizations who want to engage millennials successfully and consistently in workplace giving or volunteering will also need a reputation of transparency and integrity.

Be Crystal Clear

Millennials have higher expectations for organizations whose missions are to do good. And 60 percent say they are more inclined to give if they can see the impact of their gift.

“Today, people want to know more about a nonprofit’s goals, its impact, and the outcomes it produced. Donors want access to detailed financial reporting, too,” says Verhaeghe. “Millennials want to know about the differences a charitable organization is making before they contribute to its cause,” he adds.

Trust is a big deal to today’s donors. If a nonprofit organization doesn’t live up to certain standards of transparency, it will receive less in contributions than organizations that proactively provide data to the public.

It should come as no surprise that the characteristics of true nonprofit transparency are important to all charitable givers, not just millennials. For a deeper dive into the importance of transparency, see our corresponding article, “Transparent Reputations and Nonprofit Organizations.”

Nonprofits that evolve alongside—and effectively engage—the millennial generation will reap the benefits. Like their baby boomer parents, millennials are charitably inclined, and they believe strongly that they can change the world. But this can only happen if nonprofits them where they are—online, at work, in-person, and with transparency.

When CAPTRUST Chief Executive Officer Fielding Miller decided it was time for CAPTRUST to retool the way it communicates with clients, he knew what direction he wanted things to go. And exactly who to call on to get there.

Enter Chief Marketing Officer John Curry.

Curry’s signature salt-and-pepper coif of long, wavy hair stands out among CAPTRUST senior leadership, but he pulls it off. Curry compensates, in part, with his slant toward impeccable dress. Perhaps his colleagues would expect no less from him. He is, quite possibly, a double agent.

This 30-year industry veteran is not only CAPTRUST’s head of marketing, he is also the rhythm guitarist in the company’s in-house garage rock band, The Rollovers.

Like Curry, VESTED magazine—his brainchild and ongoing passion project—stands out among financial firms’ cookie-cutter newsletters and stock market updates.

Four years since inception, VESTED is undeniably making a difference in the lives of its more than 20,000 print and digital readers. Its Second Act heroes are lighting a path for those seeking new directions; its planning and lifestyle features, Passion Pursuits, Expert Angle, and Lasting Legacy columns (among others) explore nontraditional aspects of retirement—often told through the stories of those who have been there and done that.

I’ve got this marketing ninja for a lunchtime interview and deep dive on the magazine: what it’s all about, why we love it, and where it’s going next.

Let’s start with the basics. What is VESTED about? What is CAPTRUST trying to do with VESTED?

When we started VESTED, it was helpful to know that we didn’t want it to be about money and markets. You can get that in lots of places. We also believed—and still do—that that kind of information is not very helpful, and it’s not going to help anyone live a better life. In fact, it may fuel bad behaviors, like knee-jerk reactions to market moves, market timing, or chasing what’s hot.

That freed us up to go elsewhere. We decided that VESTED’s mission would be to inform and inspire what’s next for our readers. With all the doom and gloom we hear in the retirement industry about the looming retirement crisis, we liked the idea of an aspirational mission. We also wanted it to be full of people.

CAPTRUST is a financial services firm. Why create a magazine?

I get this question a lot.

We wanted to do something different. In a world that is moving increasingly digital, we thought there was an opportunity to put something in the hands of our clients and friends that is tangible and beautiful. The tactile aspect of VESTED is very important. It’s the weight of the paper and the coating on the cover. People always comment on the quality of the magazine itself.

VESTED’s content is different, too. We wanted to write about topics relevant to our clients’ lives. Topics that are helpful to them. We use VESTED as a way to put new ideas and possibilities for what’s next in front of them.

What’s next could be noncareer work, a new career, travel, exploring passions, learning, coping with aging, downsizing, a big family project, or thinking about legacy, to name just a few. These are hot topics for our readers, and there are not many good sources for perspective on them. A lot of our articles pull together resources from multiple sources—books, the web, TED Talks, subject matter experts—to help frame an issue or topic and provide tips for getting started if the topic resonates with them.

We spend a lot of time writing about retirement—if that’s the right word for it. We hear from clients that it’s an intimidating process, and it’s something they are uncertain about. We want to help. CAPTRUST has the experience and expertise to give our readers tips to help them achieve a more successful retirement. Often, VESTED tries to do that through the stories and lessons of people who have paved the way.

What did it take to make the magazine go from an idea to a reality?

[CEO] Fielding [Miller] and I were in the car on the way to a meeting. We got to talking about the state of our client communications—what they were and what they could be. We both wanted CAPTRUST’s brand to be more aspirational, more evergreen, and more focused on helping people realize their potential as they enter retirement.

We came up with the idea to make a magazine. When we got back to the office, I immediately went up the elevator, called everybody in marketing into a conference room, and basically said, “Holy crap! Fielding wants us to create a magazine. What do we do now?”

That was August 2014. The first issue came out in January of 2015. So you can imagine that, during those five months, we were doing everything from trying to conceive what this magazine should be, what it should look like, the paper size, the paper weight, the coatings, the regular columns and features, who the writers would be, printing, shipping, editorial voice, and featured talent. You name it. We had to decide on literally every aspect of what it takes to make a magazine. It was a lot of fun.

Tell me about VESTED’s target audience and how you landed on this demographic.

Our readers tend to be in their mid-to-late 50s or early 60s, around retirement age—maybe a few years before or a few years into retirement—who have saved and invested well. They are thinking about what’s next for their lives. We want to help this group understand what they need to know to retire successfully. We can show them some of the path forward and provide an opportunity to think differently about it.

What do you see for the future of VESTED?

So much. The magazine has really caught fire. I think there is an opportunity to extend VESTED into video, which is something we have experimented with in the past.

We also want to create a live, in-person VESTED event, in the form of a symposium that we can execute around the country. We’re interested in what we can do that will put us in touch with people in and around the markets we serve. VESTED is really becoming the CAPTRUST brand when it comes to value-added content for wealth management clients.

Where do you see yourself 10 years from now?

VESTED is the single most interesting and exciting project I’ve worked on in my 30-plus-year career. I’m in no rush to go anywhere. I’d love to still be working on VESTED 10 years from now. Maybe they’ll let me stay on as an editor and weigh in on art direction. If Fielding doesn’t mind me working out of my home in Spain, I don’t see a reason to stop.

What about your work inspires you?

Three decades in the financial services industry—mostly focused on retirement issues—and I’ve become very passionate about helping America retire successfully. And, of course, my wife, Marcela, is also in the industry, so it’s a team effort.

I also think about the work we do on a very personal basis. I always think about our clients, who, if they take our advice, can find themselves in a comfortable financial position. When they get to the point of retirement—or time to do something different—I want them to be excited about the possibilities and ready to explore the world. It would be a real shame if they didn’t get to enjoy the fruits of their financial success. And it’s easy to see why they wouldn’t.

If you’re a good saver, you may not know how to spend your money in retirement. Or you may not know where to start to engage in that conversation. One of the goals of VESTED is to give our readers a little jumpstart and show them how to think about it. We present ideas we hope readers will explore. I like to imagine that we are seeding interesting dinner-table conversations they will be having with their spouses or friends about their futures.

When did you realize you had an interest in writing?

When I got to CAPTRUST, I thought I was a pretty good writer. But I quickly found out I was in over my head. And I realized that, as head of the marketing department, the buck stopped with me. And so, I needed to get serious about it. I needed to become a student of the game. I needed to practice, and I needed to own it.

I don’t know if I’ve gotten better, but it certainly has gotten easier. In the process, I’ve come to enjoy it, and that’s why I obsess over things like grammar, writing standards, tone, and voice.

What is your favorite thing about being editor in chief for VESTED?

The people I work with on the VESTED editorial and design teams are great. And I love challenging them to think big, to make sure that the magazine is as great as it can be. Making sure it fulfills our vision is hard. Great stuff doesn’t happen by accident.

But I also love meeting the people who are featured in our magazine. They are world-class, fascinating people. By the time we do our photoshoots, I have looked at everything I can find on them. I have read all their books, read every magazine article about them, listened to podcasts they are featured on—you name it. By then, I’ve turned into a complete fanboy. It’s a bit embarrassing.

Meeting Jamal Joseph—the Second Act subject of the last issue—is definitely a highlight. I had been editing the story while reading his book, Panther Baby. Then we went to Harlem for the photoshoot. My job at a photoshoot is mostly to make the person we are photographing feel at ease and to stay out of the way. I have to admit I was a little awestruck. When I finally got going, it was great. He is a super-warm and engaging guy.

What advice would you give someone embarking on a big professional project?

Challenge yourself. The only thing that’s ever standing in your way is your preconceptions about yourself.

One day your boss’s boss is going to walk into your office and tell you to put a man on the moon. When that happens, don’t come up with 20 reasons why you can’t put a man on the moon, or why it’s scary to put a man on the moon, or why you might fail. Embrace it and put a man on the moon! How many of those opportunities do you get? So, run with it. That’s what I would tell them.

A big thank you to John Curry for spending some time with me. He is a cerebral gentleman, a pleasure to interview, and proof that rock-and-roll hair has a place in a pinstriped suit.

The billboard, sponsored by the Greater Boston Food Bank, said, “One in six Americans are hungry.” Rauch’s first thought was, “That just can’t be right.” As former national president of the Trader Joe’s grocery chain who guided its expansion from nine stores in Southern California to more than 400 stores nationwide, he knew we were in a land of plenty. In fact, from farm to fridge, we waste up to 40 percent of the food we produce, enough to fill the Rose Bowl every day. So why do nearly 50 million Americans struggle to put meals on the table?

“Having spent my career in the food industry, I knew that America had more than enough food to feed everyone,” Rauch says. “So why weren’t we? This started me down the road of discovery about the real nature of hunger in America and what we can do about it.”

That road led him to create the Daily Table grocery stores in the Dorchester and Roxbury neighborhoods of Boston. Daily Table addresses the paradoxical dual challenges of hunger and obesity by providing convenient, healthy, and surprisingly affordable food. “Think of us like a T.J. Maxx or Marshalls for food,” states the nonprofit’s website.

The food is donated or deeply discounted from well-known brands and local growers, national distributors, and nearby retailers. The food could be surplus, approaching expiration date, or imperfect in appearance. It’s food that would otherwise be destined for a landfill.

Now in its fourth year, Daily Table moves about a million nutritional servings a month into the community. That’s a million servings not coming from a vending machine, a convenience store, or a burger griddle. It’s a million steps toward a community’s healthier living, at fast food prices or less.

“Our intention wasn’t to be just a grocery store,” said Rauch. “We are a 501(c)(3) nonprofit because we are dedicated to relieving hunger and food insecurity and raising the community’s health. And we do that by masquerading as a food market.”

The Accidental Grocer

After earning a Bachelor of Arts degree in history and then waiting to hear back about graduate school, Rauch was at a crossroads. A friend who was general manager of the natural food store Erewhon tried to persuade him to come work in his company’s distribution center.

“That didn’t sound very appealing to me,” Rauch recalls. “But this was the ’70s, and the company was filled with bright-eyed, idealistic, optimistic people who were excited about food systems in the world. I thought, wow, this is an interesting group of people.” A stint with this pioneering company would fill the gap until grad school.

But he stayed and became vice president and general manager. “In the process, I started selling Erewhon products through this funny retail chain in Southern California called Trader Joe’s Pronto Market.” At the time, the markets looked like any 7-Eleven, the shelves lined with Wonder Bread, Hostess snacks, Campbell’s soup, soda, and cigarettes.

When Erewhon’s West Coast division was sold, Rauch thought about Trader Joe’s. “I had always loved interacting with the company. They were incredibly available. When I called Trader Joe’s, no one screened the call, asking who’s calling, what’s this in regard to, or is he expecting the call. If [founder] Joe Coulombe was around, someone found him and put him on the phone. I really liked that.”

This was 1977, and Trader Joe’s needed a new raison d’être. Competing with 7-Eleven was not the way forward. One differentiator was that Trader Joe’s had a successful private-label wine business, offering its own Charles Shaw wines for $1.99—“two-buck Chuck”—compared to other popular wines at $5, $6, or $7 a bottle. That model was working. Alcohol sales far surpassed food sales.

Why not do the same for food? “I spent the next year or two working with Joe to formulate the private-label program at Trader Joe’s, basically reinventing how customers think about store brands,” said Rauch. “Up until that point, ‘private label’ was just a price point, cheaper and lower quality than national brands. We turned that around and started creating destination products that were distinctive, unique, or priced significantly lower than the national brand.” The concept worked. Within 10 years, food revenues surpassed alcohol, and Trader Joe’s was poised to become a wildly successful grocery chain.

“I woke up one morning, and I had been with the company about 12 years, and I suddenly realized this is my career,” Rauch recalls with a chuckle. “I was kind of doing this while waiting to figure out what to do with my life. Suddenly I realized, I’m a grocer. How did that happen? It is a great place, with great people, very entrepreneurial, very innovative. It was a really fun, engaging, exciting place to work. Still is.”

Nudged by Coulombe, who was a big fan of business guru Peter Drucker, Rauch got his Executive Master of Business Administration degree at nearby Claremont Graduate University. “When I graduated from Drucker School of Management, the executive team at Trader Joe’s said, ‘You’re the new smarty pants business guy. You’re going to write the business plan for how we’ll grow outside of California.’”

The rest is a case study of which MBA students dream. Between 1990 and 2001, the number of stores quintupled, and profits soared tenfold. In 2008, Trader Joe’s had the highest sales per square foot of any grocer in the country, according to BusinessWeek. At the same time, Ethisphere magazine listed Trader Joe’s among its most ethical companies in the U.S.

But for Rauch, it was the right time for a change.

Graduating, Not Retiring

“It was 2008; I was 56, soon to be 57, and I had been traveling extensively with Trader Joe’s, particularly with all the expansions, opening up all the new stores,” said Rauch. “And, frankly, I wasn’t having the fun I was having before. It was a very different business. I remember going to Minneapolis in January, when it was minus 10 degrees, to look at a patch of dirt that was going to be a new store. I thought, ‘This isn’t fun.’ The ceaseless travel and the management side of the business lost its appeal for me.”

According to Rauch, the puzzles and challenges of creating a private-label program, nurturing a distinctive culture and product portfolio, scaling a nine-store chain to compete with behemoths such as Ralphs and Vons—those things were heady, but now it was time for something else.

“I didn’t know what that looked like. I had no idea what I was going to do,” said Rauch. “But I wasn’t going to call it retirement.”

Rauch spent the next year and a half doing some consulting, serving on boards and as a trustee for the top-ranked Olin College of Engineering. “Pretty quickly, I determined I wasn’t going to be satisfied just sitting on boards. A lot of it is just not as operationally satisfying for someone who had spent his life as an operator.”

An Encore Career for Social Good

A colleague at Olin told Rauch about a new Advanced Leadership Initiative at Harvard. Distinguished business professor and author Rosabeth Moss Kanter had created a program to help leaders at the top of their fields apply their skills to national and global social issues in their next life stage, particularly relating to health and welfare, children, and the environment. The first session was underway. A Boston Globe article sealed the deal for Rauch. This was the next step.

“What attracted me was the concept of taking people who had completed their primary careers but still had gas in the tank—10 to 15 years or longer to still be actively engaged—and let them have the use of the college, all the schools, working with faculty and students—to figure out how to tackle some major social ills,” said Rauch. “Then it hit me. This isn’t about learning, this is about doing. This is about taking your lifetime experience and adding some knowledge and information to social enterprise.”

Then came the billboard—one in six Americans hungry in a land of plenty, including plenty of waste. Rauch reflected on our dysfunctional food culture.

Earlier generations had experienced food scarcity through economic depressions, wartimes, and crop failures in the era before electricity and refrigeration. Baby boomers could be the first generation that took abundance for granted.

“At first I was thinking, it’s just a distribution issue, a logistical question. I thought I could help with that, but it turned out it wasn’t that. You’d better really understand what the problem is if you’re trying to solve it. Otherwise you’re going to come up with some elegant and beautiful solutions to the wrong problem,” says Rauch.

Nutrition with Dignity

“Generally speaking, people who are struggling economically can’t afford fresh fruit and vegetables, so they end up eating high-sugar, highly processed empty calories—junk food, if you will,” says Rauch. “So, the solution isn’t what I thought it was. It isn’t about distribution bottlenecks. They’ve already got a full stomach. We’ve got to get them a healthy meal.”

“That turns out to be complicated, because low-value calories such as corn and high fructose corn syrup are cheap. Nutrients are expensive. So, the question became, how can we afford to provide fruits and vegetables in an economically viable manner?”

Why not launch a massive fundraising effort and create another food bank? Food banks fill a critical need. For instance, Feeding America—the third-largest U.S. charity—feeds more than 46 million people through its vast network of food pantries, soup kitchens, shelters, and other community-based agencies.

However, a Feeding America leader told Rauch that many people who qualify for food charities don’t use them. Why? Is it transportation, immigration concerns, or language barriers?

“It turns out it’s much simpler than that. They’re ashamed, embarrassed. They don’t want a handout. That was a big awakening. Many people would rather keep their dignity than their health. I realized if we’re going to solve this problem at scale, we had to come up with a way that the person in need has a dignified exchange,” says Rauch.

“A handout sets up an imbalance,” says Rauch. “If we’re selling the product, even if it’s for pennies on the dollar, people are going to interact with us in a very different way. In that dynamic, they hold the power of the purse; they end up, by definition, having a sense of agency and dignity.”

Friendly Retail Stores

The Dorchester Daily Table store opened in June 2015, followed by a second location in nearby Roxbury. Membership is free, and Daily Table currently has 42,000 members. Rauch is scouting for third and fourth locations—and eyeing expansion into other states.

The stores offer an upbeat, clean, and friendly retail environment. Hand-lettered signs add a vintage market feel. The aisles and crates are brimming with fresh, healthy food options at budget-friendly prices: a pound of bananas for 29 cents, a can of tuna for 55 cents, or a dozen eggs for $1.19.

Instead of a burger and fries, busy customers can choose a nutritionist-approved dinner of two pieces of chicken, brown rice, and vegetables for $1.99 or pick up ready-to-cook and grab-n-go prepared meals. A teaching kitchen offers free cooking classes several days a week. More than 100 educational modules show members how to have food be tasty, nutritious, and healing.

“I don’t think you’ll find any place in Massachusetts where you can get a prepared meal with the recommended nutritional values for $1.99,” said Rauch. “It’s made possible because Daily Table works with a broad network of suppliers who offer donations and special buying opportunities. Food that might otherwise go to waste is now crafted into meal options that compete with unhealthy fast food options.”

Nutrition by Design

Rauch worked with a task force of nutritionists to quantify “healthy” to guide food decisions. For the last four years, Daily Table has met or exceeded these guidelines in food prepared in-house and purchased and donated food items. The stores do not even sell soda.

In 2017, the head of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) visited Daily Table along with an entourage of U.S. Department of Agriculture representatives. He declared Daily Table to be one of the only stores where food stamp recipients can get the 2,000 calories a day of nutritious food they should be eating and still have money in their pockets at the end of the month.

“We’re very proud of that, because for us, it’s the litmus test of how well we are meeting our mission of delivering nutrition at an affordable value,” says Rauch.

The Bottom Line

While Rauch would love for Daily Table to be self-sustaining, it does rely on monetary and in-kind donations. “I don’t care if you’re Walmart or Costco, you can’t bend the cost curve enough to have nutritious food compete with junk food. You can’t get fruits and vegetables to be as cheap as sugary, processed food,” says Rauch.

About 20 to 30 percent of merchandise is donated; the rest is purchased at discounts. Daily Table also relies on 200 to 300 hours a week from volunteers working alongside 60 employees hired from the local community who are paid 25 percent more than local minimum wage.

“We cover about two-thirds of our expenses from our own generated revenue, but we hope with more stores—and we are fundraising to open additional stores—we can come close to breaking even,” says Rauch. When the economics are viable, the hope is to expand the mission across the country.

For Jane Ehrman, now 68, a life-defining crisis came when she was a 37-year-old mother diagnosed with aggressive breast cancer. Ann Kaiser Stearns, 76, says her life was rocked by a long-ago divorce and a close friend’s suicide. Charly Jaffe, 29, endured a series of crises, including sexual assault, a severe sports injury, and a near-death experience when she was just a young college student.

All of these women say they are stronger today for the trials they’ve faced—and have dedicated their lives to helping others find that strength.

Ehrman, who lives in Cleveland, is a stress relief coach for first responders and people facing medical crises. Stearns, a professor at the Community College of Baltimore County, is a psychologist and author of several books, including Living Through Personal Crisis. Jaffe left a job at Google to help run a yoga school in Australia and now works as a crisis counselor, while finishing a master’s degree in psychology and education at Columbia University. She also helped her father, entrepreneur Richard Jaffe, write a book called Turning Crisis into Success.

Crisis changes all of our lives, says cognitive scientist Art Markman, a professor of psychology at the University of Texas at Austin.

“Those kinds of events create a tear in the fabric of your life story. Your life was one way before the event and another way afterward,” he says. Once a crisis recedes, Markman says, “Your job is to reweave the story of your life.” Most of us manage to do that, eventually.

But along the way, many of us make a few very human mistakes.

This Is Your Brain on Crisis

The first stage of a crisis is often an emergency—the moment you see your spouse collapse from a heart attack, smell the smoke coming from your kitchen, or hear the roar of an approaching tornado.

At such moments, Markman says, our bodies and brains prepare for action: “You breathe in a way that brings a lot of oxygen in; your heart rate goes up. Your focus of attention narrows so you can pay attention to what is going on in that situation.”

It’s the classic fight or flight response, and, when it works well, it helps us do the things we immediately need to do—calling 911 and getting an aspirin for the heart attack victim or gathering family members to escape the fire or reach the basement before the tornado hits. People in this state famously find the strength to lift heavy objects and fight off wild animals.

But people in danger also make baffling errors of judgment. They stand on the beach after a tsunami warning or run back into a burning house for a wallet. They convince themselves that their drooping face can’t possibly be a sign of stroke and take a nap instead of going to a hospital. That’s why we have drills and awareness campaigns to teach us what to do in such emergencies. Practice and a script can help us overcome denial and shock, Markman says.

That means, he says, that many of us stumble around in a state in which our thinking and emotional skills are dulled.

Missteps During Crisis

Here are some common mistakes people make while in that fog, according to the experts.

- They make big, irreversible decisions. Widows sell the family home. Angry ex-spouses burn old photos. Hurricane survivors flee their communities, leaving lifelong support systems behind. Stearns, the Baltimore psychology professor, says her rule of thumb for anyone in crisis is “don’t destroy it, don’t give it away, and don’t sell it.” Markman agrees: “Whenever possible, kick the can down the road,” and save big decisions for later.

- They isolate themselves. “Social interactions are a wonderful salve,” Markman says. Stearns says our need for social support in times of distress goes deep. “We were made to be pack animals. We are made to survive with others.”

- They confide in the wrong people. “It’s really important to avoid negative people,” Stearns says. “There are people who will judge us, people who will not keep confidences, people who will try to fix us, and some of those wrong people are our own family members, unfortunately.”

- They pretend to be fine. When Jaffe returned to college after a serious injury and life-threatening complications, she was suffering symptoms of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. “But I didn’t want to share it with anyone because I was afraid people would think I was crazy,” she says. “Instead, I would have a panic attack, wash my face, and go back to class and ask for the notes I had missed.”

- They reject professional help. “It’s not a bad thing to have someone to talk to who has some training and has no vested interest in how things come out,” Markman says. It’s especially urgent to reach out if you suffer symptoms of post-traumatic stress, such as flashbacks, nightmares, severe anxiety, or symptoms of depression, such as hopelessness, lack of interest in life, or thoughts of suicide.

- They beat themselves up. Too many people listen to a harsh inner judge at times of distress, says Ehrman, the Cleveland stress relief coach. “We tell ourselves we are stupid, we are incapable, or we never do anything right.” Many ruminate on upsetting events, looking for where they went wrong, Markman says. “They keep asking, ‘Did I miss the signs? Is there something I could have done?’”

What Happens When a Crisis Lasts?

When disaster leads to an ongoing crisis—a long hospital stay, a ruined home, the aftermath of a death—our brains and bodies often stay in stress mode. We may not have a script for what to do then.

That’s the position many people find themselves in when they become caregivers for a loved one with dementia or another serious long-lasting condition.

Stearns says too many people in that difficult situation succumb to what some social scientists call John Henryism—the affliction of the legendary steel-driving man who worked so hard at a seemingly impossible task that he died.

In her book Redefining Aging: A Caregiver’s Guide to Living Your Best Life, Stearns urges caregivers to find other role models. While we often express admiration for apparently tireless caregivers, those who never take a break risk their own health, she says.

Caregivers who find and use outside support are more likely to find meaning in their caregiving journeys, Stearns says. Those who go it alone are more likely to feel overwhelmed and spent.

Finding a Way Through

Most people are more resilient in a crisis than they think they will be, the experts say.

“Bear in mind that every life is ultimately touched by something that we consider tragedy,” Markman says. “Human psychology is fairly well designed to withstand those crises.”

While there is no single correct path to healing, “hope is looking at your situation realistically and finding a way through,” Ehrman says.

In her case, finding a way through a mastectomy and chemotherapy meant going to a therapist who taught her how to take her mind to better places—through a technique called guided imagery. Once she was healthy, she went back to school to get a master’s degree in education, with a focus on mind and body medicine. Today, she teaches guided imagery and self-hypnosis to others in distress.

Stearns also responded to crisis, a divorce at age 27, by going back to school. Seven years later, she had a doctorate degree in psychology. Later, she adopted two daughters and went on to write four books. She has faced other crises such as the suicide death of a friend and the deaths of family members, including her mother.

Losses never get easy, she says, but you do learn from them. “One of the most important things to understand from the beginning is that you have to be kind to yourself, because healing takes time, and you are going to feel bad before you feel better,” says Stearns.

Here are some things you can do to ease the pain: