-

Solutions

- Solutions

- Individuals

-

Retirement Plan Sponsors

- Retirement Plan Sponsors

- Corporations

- Educational Institutions

- Healthcare Organizations

- Nonprofits

- Government Entities

- Endowments & Foundations

- See All Solutions

Comprehensive wealth planning and investment advice, tailored to your unique needs and goals.Investment advisory and co-fiduciary services that help you deliver more effective total retirement solutions.CAPTRUST provides investment, fiduciary, and risk management services for nonprofit organizations. -

About Us

- About Us

- Our People

- Our Story

- Learn About CAPTRUST

-

Locations

-

Resources

- Resources

- Articles

- Podcasts

- Videos

- Webinars

- See All Resources

In this issue, we explore the latest Social Security projections and insight on planning for the future of the program, along with a look at the importance of creating and maintaining a home inventory.

Q: I’ve heard recently about financial issues Social Security is facing. Is there reason to be concerned?

A: The financial solvency of Social Security is a long-standing issue, and the media tends to sensationalize it. The latest bout of media hype started at the end of April when the trustees of Social Security released their latest financial projection. While the program’s long-term outlook has not changed much from last year, what the media didn’t tell you is that it is slightly improved from 2018 due to the health of the labor market.

According to the projection, outflows from the retirement program will exceed its income in 2020. The problem stems from people living longer, a smaller working-age population, and an increase in the number of people in retirement. By 2050, the number of Americans age 65 and older will increase from about 48 million today to more than 83 million.1 As a result, more people will be taking money out of the system, and fewer will be paying into Social Security.

What’s going to happen? First, it is important to say that this program is not going away. According to ssa.gov, among elderly Social Security beneficiaries, 48 percent of married couples and

69 percent of unmarried persons receive 50 percent or more of their income from Social Security. Congress will have to fix the program, although the fix may come with changes to contributions and benefits and may require means testing of some kind.

Considering the likelihood of changes, it’s best to make sure your retirement plan accounts for the uncertainty:

- Check your benefits. Estimate your Social Security retirement benefits based on your actual earnings record using the Retirement Estimator calculator on the Social Security website (ssa.gov). You can create different scenarios based on current law that will illustrate how different earnings amounts and retirement ages will affect your benefits.

- Stress test your plan. If you want to make sure your financial plan for retirement will work—even if Congress takes action that may lower Social Security benefits—ask your financial advisor to model multiple retirement income scenarios. For example, see what your retirement plan looks like if Social Security is reduced by 10, 20, or 30 percent.

- Take action, if necessary. If you find that you can survive with the reduced program benefits, anything you actually receive will be a boost to your income. If the analysis shows you need to consider putting aside more money to make up for a cut in benefits, work with your financial advisor to create a plan that supports those needs.

Remember that everyone’s financial circumstances are unique, so work with your financial advisor to come up with a plan that works financially for you and also gives you comfort that you’re on the right track.

Q: What is the point of a home inventory? Do I need one?

A: Many of us have made our homes in areas prone to wildfires, flooding, tornadoes, or hurricanes. But even if your home is not in such an area, you might still find yourself living through the type of disaster that makes the evening news. A home inventory is a simple way to give you and your loved ones a place to start picking up the pieces should your home experience a catastrophic event.

A home inventory is a complete and detailed written list of the property that’s located in your home and stored in other structures like garages and toolsheds. It should include your possessions and those of family members or others living in your home. A home inventory can help substantiate an insurance claim, support a police report when items are stolen, or prove a loss to the Internal Revenue Service.

In the event of a disaster, a home inventory will spare you the headache of having to create a listing of all your possessions based on memory alone.

Here are some tips to get started.

- Tour your property. Look around every room in your home and the spaces where you have items stored, such as a basement, garage, or shed. You can go low-tech and write everything down in a notebook or make a visual record of your belongings by taking videos or pictures. Be sure to open cabinets, closets, and drawers, and pay special attention to valuable and hard-to-replace items.

- Be thorough. Your inventory should be detailed. When practical, include purchase dates, estimated values, and serial and model numbers. Refer to colors, dimensions, manufacturers, and materials whenever you can. If you can locate appraisals for valuables and receipts to support big-ticket items—even better—include copies of those too. Try to identify every item that you would have to box or carry out if you were to move out of your home. Don’t forget tools and outdoor equipment like lawn furniture and barbecue grills. The only things you should leave out of your inventory are the four walls, the ceiling, the floor, and the fixtures.

- Keep it safe. You will need two copies of your home inventory: one at your home where you can easily access it and another copy somewhere else to protect it in the event your home is damaged by a flood, fire, or other disaster. This might mean giving it to a trusted friend or family member for safekeeping. If you’re tech savvy, storing it on an external storage device you can take with you or on a cloud-based service might be a good option. Regardless of whether the inventory is recorded on film, computer software, a sketch pad, or the back of an envelope, keep a copy of it stored somewhere safe, like a safe-deposit box at a bank or your desk at work.

- Update it periodically. As valuable or important items come into your possession, add them to your inventory as soon as possible. For accuracy, you should review your home inventory annually. It’s also a good idea to share an updated annual version with your insurance agent or representative to help determine whether your policy coverage and limits are still adequate.

Hopefully, you’ll never have to use your home inventory, but if you have to deal with a catastrophe, you’ll be happy you took the time to make a permanent record of all your possessions.

1 Ortman, Jennifer; Velkoff, Victoria; and Hogan, Howard, “An Aging Nation: The Older Population in the United States,” Census.gov, 2018.

As people begin to consider end-of-life planning, they often reflect on what type of legacy they will be leaving behind. Discussions about heirlooms and what’s going to be gifted to family members and charities often feature prominently. But what about gifting life?

Making the decision to become an organ donor is a deeply personal one—one that could provide immeasurable lifesaving benefits. Whether donating organs to those in desperate need or donating a whole body to the advancement of medical research, the donor’s gift is a way to give death meaning and to keep the memory of his or her life alive.

One Life Touches Many

Gina Kosla was 18 years old and attending Coastal Carolina College when she started experiencing shortness of breath. A cystic fibrosis sufferer, she had contracted pneumonia. Her family made a decision to fly her to Duke Medical Center in Raleigh, North Carolina.

Thankfully, Gina only had to wait six days to receive a double lung transplant. “We felt elated. In the same thought, there is someone out there who may be passing this world,” said Reyna Kosla, Gina’s mother, when describing the moment they found out an organ was available. “There is also a family and friends grieving. Whoever the donor may be at whatever time God designates this to happen, we all must think of the donor too.”

Gina’s new lungs came from Jillian Koch, a healthy 14-year-old girl, who was dreaming of moving to San Francisco to become a sculptor, when a sinus infection traveled to her brain causing a fatal subdural empyema. Deanne, her mother, describes the reason behind donating her daughter’s organs: “I needed my daughter’s life, no matter how short, to have meaning. But most of all, I wanted a part of her to live on. I simply would not accept that this was all there was, and I refused to let Jillian’s story end there. I never realized the profound impact our decision would have. It has changed my life forever.”

Jillian’s organs were also able to save a man who had been waiting two years for a left kidney and pancreas, a mother of two from New York with her right kidney, and a woman who had less than 24 hours to live with her liver. Jillian’s largest donation, her skin, will better the lives of dozens of people, such as burn victims and babies born with serious physical abnormalities.

People who decide to become organ donors can save up to 12 lives—if the hands, face, and corneas are donated—and those who choose to donate tissue can help improve the lives of up to 50 people, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The department also states that another person is added to the national transplant waiting list every 10 minutes and, as of January 2019, the total number of hopeful organ recipients was 113,000. This number is surprising since 95 percent of U.S. adults support organ donation. Unfortunately, only 58 percent of Americans are actually registered as donors.

The disparity between those who support organ donation and those who donate could be partially attributed to lack of communication. Whether donating intentions are included in a will or through a discussion with family members, it’s important to make your intentions clear ahead of time.

Those wanting to sign up as donors can go to organdonor.gov to register. If you live in a state that offers the option to become an organ donor on your driver’s license, you can always be added to the registry through the selection of the donor option.

Living Donors Gift Second Chances

Dr. Denise Laurienti is a nephrologist in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. She specializes in kidney care and the treatment of kidney diseases. She is also a kidney donor. In January of 2018, Laurienti donated one of her kidneys to her sister, Sarah Queen, who has been battling lupus since she was 7 years old.

“Ironically, I am a practicing nephrologist,” says Laurienti. “So, I see patients needing kidney transplants every day. I am frequently encouraging patients to ask family members or friends to be donors for them. I really can’t imagine how hard that would be to have to ask your loved ones. I really didn’t want my sister to ever have to ask people. I was so happy that I was a perfect match and that she didn’t have to do that.”

According to the American Kidney Fund, the average wait time for a kidney from the national deceased donor wait list is five years. Nearly 100,000 people are on the waiting list for a kidney transplant. Many more are waiting for a kidney than for all other organs combined.

A year after Laurienti’s and Queen’s surgeries, they’re both doing great. Laurienti said of her sister, “She has been skiing twice in the past year and really has had no issues. Every now and then, I have to be sure she is getting labs checked. She feels so good I think she forgot she had a kidney transplant.”

Through Laurienti’s selfless gift, she’s improved her sister’s quality of life, and now they both have the opportunity to create more memories together, as a family, for years to come.

Donating to Research Creates an Impactful Legacy

Consider how many lives could be saved if more people included whole-body donation with their end-of-life planning. Perhaps the most selfless way to leave a legacy of purpose is to donate with the aim of establishing cures and understanding.

Whole-body donation is predominately used for teaching medical students, but, in other cases, donations can help educate forensic teams on how bodies decompose, aid in the discovery of new treatments and surgical approaches, and assist in the testing of new medical devices.

These programs depend on the altruistic nature of donors to advance the medical field. According to Katrina Hernandez, vice president of donor services for Science Care, which serves as a link between donors and medical researchers, “Each donor brings a project one step closer to its goal.” Doctors and scientists wouldn’t be able to progress their understanding of diseases and discovery of treatments without whole-body donors.

Science Care is one of several organizations helping to facilitate the donating process. Each donor who goes through the organization contributes to six research projects, such as testing for earlier detection of Alzheimer’s disease, research into the latest drug therapies, and surgical training for physicians learning to perform lumpectomies and mastectomies for breast cancer.

Perhaps surprisingly, it’s easy to register to donate your body to Science Care or similar organizations. The only age restriction is that the potential donor must be 18 to join the registry. If the donor is still alive, he or she can complete a form, found online at sciencecare.com, and if the person has already passed, family members can call 800.417.3747 to register and go through a short medical screening that determines if there is a match with an ongoing research project.

Once a body has been accepted, Science Care covers all the costs, including transportation, cremation, and the filing of the death certificate.

The U.S. doesn’t have a centralized agency for whole-body donations. However, the American Association of Anatomists has come up with a policy for how bodies should be handled when they’re donated. States vary in how they accept applications for whole-body donation and where a body is gifted. In some states, such as Nebraska, donors can determine which medical institution they’d like to go to. Unlike organ donation, the age of the donor doesn’t matter, and someone can pledge to be a donor at any point during his or her life.

Whole-body donation is a socially responsible way to leave behind a substantial legacy. Not only is a donor providing a vessel to save lives, but he or she is also giving hope to future generations. Hope that doctors and scientists will discover cures for diseases such as Alzheimer’s, blindness, or even cancer. Hope that doctors will learn new surgical procedures that will help improve the future for us all.

Receiving a financial windfall should be a positive milestone that permanently alters an individual’s or family’s future for the better. Yet, gaining immediate and substantial wealth can often have the opposite effect, leading to a new set of challenges that can put that wealth at risk.

The prevalence of squandered wealth has become so commonplace that it has spawned its own financial term. Sudden wealth syndrome, a condition first identified by psychologist Stephen Goldbart in the late 1990s, describes the feelings of stress, guilt, and similar emotions associated with the gain of an often-unexpected financial windfall. Goldbart is co-founder of the Money, Meaning, and Choices Institute (MMCI), a group of psychological professionals who work with wealth holders and their financial advisors to address the emotional issues and challenges of wealth.

As MMCI explains on its website, society equates money with happiness and success. Most of us have a hard time believing that the rich have problems with their wealth. The institute has identified several primary symptoms of sudden wealth syndrome, including:

- Recurrent and persistent thoughts and impulses related to money;

- Anxiety and depression in response to stock market volatility—what they call “ticker shock”;

- Extreme guilt that inhibits good decision-making and leads to behaviors that punish individuals who believe they do not deserve their wealth;

- Confusion over identity, whether the suddenly wealthy are the same people as before and how that should affect their relationships and priorities; and

- Depression from the realization that gaining all the material things desired does not lead to happiness and satisfaction.

Other organizations have also been established to address the financial and emotional issues of sudden wealth, including the Sudden Money Institute, whose founder, Susan Bradley, created the Certified Financial Transitionist® designation.

“These struggles may result in social isolation, the breakdown of relationships, mental and physical fatigue, depression, and, in some cases, utter hopelessness,” explains CAPTRUST Financial Advisor Cathy Seeber.

MMCI views sudden wealth syndrome as a turning point in a person’s life that, if dealt with effectively, can be transformative and beneficial to not only that individual and his or her family but also to the larger community.

We have all heard about lottery winners or professional athletes who squander their fortunes, but this same sudden wealth syndrome can also impact the beneficiaries of more common financial windfalls.

A female client of Seeber’s, for example, acquired an eight-figure divorce settlement that was accelerated by the death of her former husband. The sudden wealth sparked an emotional response, causing the woman to move to Los Angeles, buy a mansion, and gift a large sum to her son to provide for his future. In just a few years, her client’s assets shrank from $13 million to $8 million.

“Wealth creates emotion, and emotion drives decision-making. Acknowledging this is a first step to coping with sudden wealth,” explains Seeber, one of a select group of Certified Financial Planners® who is also a Certified Financial Transitionist®. This is the first designation in the human dynamics of financial change and transition in the wealth management industry. Seeber’s training enables her to address the feelings and values triggered by sudden wealth in addition to the traditional financial consequences.

How wealth is acquired can often determine the best strategies for managing it. An inheritance or life insurance settlement from the unexpected death of a family member comes with its own emotional and financial issues, while the unsolicited sale of a business may also leave a business owner unprepared to deal with his or her new reality. Other wealth transfers are more predictable, such as a large sale of stock, a company going public, or the passing of a loved one with a terminal condition.

“You want to help people figure out how they will adapt to change when the windfall occurs, and you want to do this ahead of time whenever possible,’’ says Seeber, who works with clients across the country. “All these decisions impact a person’s well-being.”

“The root cause of a client’s lack of implementation of sound advice is his or her inability to adapt to change. Anticipation of a life-changing event, experiencing the actual event, and integrating the event into your life can involve a tremendous amount of internal realization. When the work isn’t addressed because no one notices it’s there, negative consequences occur,” says Seeber.

From a tactical standpoint, Seeber advises sudden wealth recipients to resist the urge to act rashly. Instead, she suggests putting newly gained assets in a safe place—such as a money market account or certificate of deposit—allowing adequate time to prioritize their situations and form a plan.

Angat Saini, an attorney with Accord Law in Toronto, also recommends depositing most newly acquired assets in an insured account, but says allowing for a small spending spree can be a helpful part of the transition process. “Take some of that money and spend it right away—in order to satisfy the urge to impulse spend,” Saini says. “That way you can get that urge out of your system while a long-term financial plan is being created.”

Dealing with such urges and emotions are so ingrained in a person’s psyche that Seeber and other financial planners often recommend assembling a planning team that includes not only a financial advisor, estate planning attorney, and accountant, but also a therapist.

Such expertise can help individuals not only cope with their sudden wealth but plan prudently for the life changes that wealth will bring.

“Sudden wealth syndrome is really not a syndrome because it’s not a group of signs and symptoms,” Seeber says. “Most recipients don’t see it coming, although there are some who go through the anticipation of sudden wealth.”

Seeber educates clients on the four stages of financial transition associated with a financial windfall:

- Anticipation. Prepare for an event that has not yet occurred.

- Ending. Some aspect of life has come to an end, and perhaps your identity has changed as a result.

- Passage. It takes time to relate to the change and adapt to it.

- New normal. Establish the beginning of a new life after the event has been fully integrated.

Not every instance of sudden wealth comes with an anticipation stage, but they all involve a passage from an individual’s or family’s former life to a life with significantly more financial assets. The passage stage can last years. “Some people try to force passage, but this is an important learning stage, where you can dream and set expectations and build the brain trust of your financial plan,” Seeber says.

During the passage, individuals’ feelings can run the gamut from the power of possibility to fear, anxiety, chaos, and even survivor guilt. Many sudden wealth recipients fear their identity will be compromised, while others become mentally and physically fatigued from dealing with all the new issues that wealth creates.

Some recipients of sudden wealth worked diligently their entire lives to realize a liquidity event such as the sale of a business. Such individuals may immediately consider the tax and wealth transfer implications or the need to invest their proceeds. This can be of concern to older wealth recipients who may plan to pass on their windfall to heirs. Saini suggests establishing trusts as an effective way to distribute wealth—both gifting assets during the recipient’s lifetime and reducing estate taxes upon death.

A complete understanding of the purpose of the new money and the outcome the individual would like to create is also crucial. An exercise in managing the expectations of others is equally as important. “Most people jump right to the financials, but if they don’t understand the why of their wealth, then the what doesn’t matter,” Seeber explains.

Instead, she recommends asking three important questions when facing a life transition: What do you need to protect? What do you need to let go of? What “new” needs are going to be created now, soon, and later?

This third question can set the stage for assembling the brain trust that will help form a comprehensive financial plan. As Seeber likes to say, “Good decisions make a

good life.”

It’s a common estate planning worry. Would a large inheritance squelch your children’s drive to carve their own paths in life? Billionaire Warren Buffett of Berkshire Hathaway has been suggesting for decades that you should leave your children enough money so they feel they can do anything, but not enough so they’ll do nothing.

It’s a conundrum many parents and grandparents will have to face in the coming decades. Over the next 25 years, a staggering $68.4 trillion in wealth is expected to transfer between generations, according to a 2018 report from research firm Cerulli Associates.

Are the heirs prepared to handle all that money? There’s a lot to worry about. A nest egg intended to cushion kids’ lives could instead lead to failure to launch. Kids could spend their way through hard-earned fortunes in a few years. Too much comfort could sap their natural ambition. Also, they might be treated differently by people because of their money or fall victim to gold diggers and false friends.

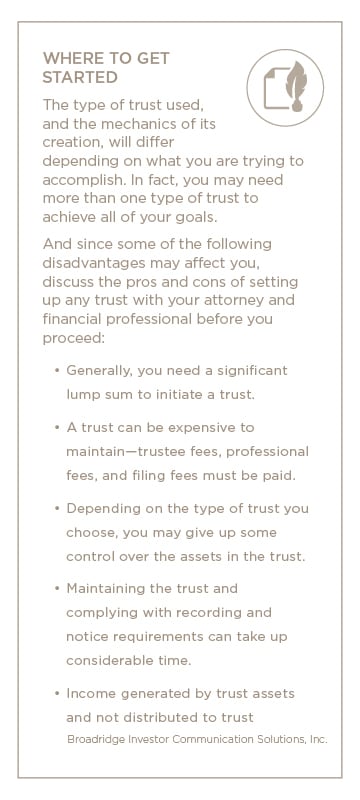

The best solution? Estate planners say a well-designed trust can provide families with plenty of protection against inheritance loss or inadvertently creating a stereotypical trust fund baby.

Influencing Heirs from the Great Beyond

Estate planning attorney Tyler Britton says he’s noticed an interesting difference in the way baby boomers are now using trusts for the upcoming generation of millennial heirs. “As an estate planner, I am seeing an increase in the amount of conditions found in trust documents,” says Britton, professor of trust and wealth management at the Lundy-Fetterman School of Business at Campbell University in Buies Creek, North Carolina.

The individuals creating the trusts want to set up guardrails that take into account the beneficiaries’ different lifestyles, priorities, and desires. These conditions allow a grantor to feel like he or she is still in control during his or her lifetime or after death. Perhaps it’s no surprise that the cohort that invented helicopter parenting would try various avenues to micromanage their survivors’ financial paths—even after they depart this life.

A trust is basically a legal agreement in which one party—called the grantor or trustmaker—puts assets (like real estate, cash, stocks, or bonds) in the care of another party, the trustee. The trustee manages the assets and carries out the instructions over time, for the benefit of a third party, the beneficiary, who could be a person or an institution.

Doesn’t a last will and testament take care of all that? Only partially.

A will gives instructions for distributing your property and is essential for naming guardians for minor children. But you typically can’t set specific conditions in a will, such as requiring your daughter to finish medical school in order to inherit your house. With a trust, you could make such a condition—or virtually any condition—giving you greater control over the distributions that are made.

The Flexibility of Revocable Living Trusts

There are many types of trusts, but the most common is a revocable living trust. It’s called “living” simply because it goes into effect while you’re alive, and “revocable” in that you are free to change the instructions you provide.

“A trust allows a grantor to specify conditions for receipt of benefits, such as income or principal. Furthermore, a trust allows a grantor to spread trust income or principal over a period of time, instead of making a single, lump sum gift,” says Britton.

For example, you can set age-based payouts. “Twenty or 30 years ago, it was common for a grantor to specify that his or her heir could not access trust principal until the heir attained the age of 21 or 25,” says Britton. “With millennial heirs, some grantors are opting to set the age to receive trust principal to 30, 35, or even 40. Their reasoning varies from apprehensions about millennial spending, saving, and work ethic to concerns about creating trust fund babies.”

A trust can be set up for a specific number of years or for the child’s lifetime, for example. The trustee could manage the principal and use investment income to pay distributions to the child. A drawn-out payment schedule, such as a distribution every five years, can prevent the inheritance from being spent too quickly.

“Other common conditions include postsecondary education requirements and drug testing,” says Britton.

Irrevocable Living Trusts Provide Liability Protection

Irrevocable living trusts can’t be terminated and are very difficult to change. Such trusts can be used to reduce taxes or protect assets against creditors or lawsuits.

“A common use for an irrevocable trust is to provide asset protection for a grantor and his or her family. By placing assets into an irrevocable trust and naming an independent trustee, a grantor relinquishes control over and loses access to trust assets. Therefore, if structured properly, the assets in an irrevocable trust cannot be reached by a grantor’s creditors,” says Britton.

That doesn’t mean you can escape existing legitimate debts just by moving all your money into an irrevocable trust.

“If a grantor conveys assets to an irrevocable trust in order to defraud or delay a legitimate creditor, a grantor is engaging in fraudulent conveyance. If a creditor can prove fraudulent conveyance, a court can reverse a grantor’s asset transfer to a trust and allow creditors to access trust property to satisfy judgments,” cautions Britton.

Spendthrift Trusts Protect Heirs from Themselves and Others

A spendthrift trust won’t turn your heirs into financial whizzes, but it can safeguard property in the trust from loss. “The term ‘spendthrift’ is often misleading. Not only does this type of trust protect heirs who lack proper judgment when it comes to spending money; this trust also protects financially responsible heirs from certain lawsuits and creditors,” says Britton.

While money is in the trust, your heir can’t spend it, give it away, or lose it. “In other words, a beneficiary cannot spend or pledge his or her interest in a trust, and certain creditors cannot seize a beneficiary’s interest in the hands of a trustee,” says Britton. Once it’s paid out from the trust, however, the beneficiary can spend the money in any way he or she sees fit, and it would no longer be protected from creditors.

Special Needs Trusts Protect Eligibility for Benefits

Another reason for an irrevocable trust would be to provide financial support for a child with a disability, while protecting his or her eligibility for public assistance. You can put money or property into a special needs trust and appoint a trustee to use the funds to purchase necessities for the beneficiary. The beneficiary doesn’t own the property in the trust, so it would not prevent the person from applying for government benefits.

Trusts are traditionally associated with the very wealthy, but even middle-class families can take advantage of trusts to clarify how assets should be distributed after death. An estate planning professional can help you design a trust that best fits your particular situation.

The next time your stomach is growling as you dash from one office building to the next, you might want to watch your step. There’s a new kind of street food craze sweeping the country, and its ingredients could be right under your feet.

Urban foraging is an inside-the-city-limits version of the ancient practice of searching for and utilizing edible wild plants. And while it might seem surprising to think that a big-city environment could provide a between-conference-calls snack—much less the ingredients for a full meal—urban foraging has become wildly popular.

Chefs are taking to the streets to add foraged greens to their dishes. Parks and nature preserves are offering guided wild edibles tours. And while many cities are beginning to regulate urban foraging in public spaces due to its growing popularity—more on that later—municipal areas still offer savvy foragers an opportunity to spice up their daily meals with highly nutritious wild foods.

“Trying to survive on wild plants would be a serious challenge, but a diet made up of 10 percent wild foraged foods is as easy as can be,” says Mark Vorderbruggen, a Texas-based research chemist and edible wild plants expert who teaches urban foraging techniques at the Houston Arboretum and other Lone Star nature preserves. “And many of these plants are literally growing up around the sidewalk, so it’s mainly a matter of opening your eyes to what’s right there under your feet.”

Consider the redbud, a small flowering tree that grows on city streets across the country. It’s one of the earliest flowering trees, with stunning red-purple flowers that cling directly to the tree’s branches. Even if you don’t know the plant by name, it’s a good bet you’d recognize a redbud once it was pointed out.

And redbud is a prime urban foraging plant, says Vorderbruggen. In the spring, those striking flowers that turn the heads of passersby are delicious when plucked from the tree and eaten raw. They can be added to salads or used to top cupcakes and pies. And a few weeks after blooming, each of those flowers turns into a peapod. “Just like something you’d see in the grocery store,” Vorderbruggen says. “When they’re about a half-inch long, they are tender and delicious, and you can eat them raw or add them to a stir-fry dish.”

All from a common landscaping tree.

It’s the same with plants such as purslane and lambs- quarter, wild onion, and peppergrass. Urban environments around the country are chock-full of edible wild plants, from lesser known fruits such as persimmon to a virtual salad bar of greens that grow from sidewalk cracks to front yards to greenways. In the South, wax leaf myrtle is an oregano-like plant that adds a definite dash to lasagna. The tender leaves of common plantain have a nutty, close-to-asparagus taste and can be quickly stir-fried in olive oil. The young shoots of Japanese knotweed—a hated invader across much of the country—have a lemony, rhubarb-ish taste that’s led them to the kitchens of Manhattan chefs.

In fact, many of what we consider weeds in North America are actually beloved garden plants brought over by European settlers that now grow wild. Sow thistle and dandelion, Vorderbruggen says, were cultivated as food plants. But since they don’t have pests and predator controls in the American environment, they’ve spread so quickly and far that we now consider them weeds.

And while toxic plants abound—making plant identification a critical foraging skill—these wild foods can be very healthy. Foraging experts point out that the plants tend to be denser with nutrients than many of their cultivated counterparts, thanks to growing in soils that haven’t been depleted over decades of farming.

Collectors need to be aware of areas that have been sprayed with herbicides or pesticides, and stay away from older buildings with lead paint that can leach into soils. But many wild plants have dense root systems that tap minerals deep in the soil and transfer that bounty to delicious leaves, shoots, and flowers.

Every Rose Has Its Thorns

The growing interest in wild edibles has some cities working to make sure foragers don’t love a local park’s hedgerows to death. Cities such as Chicago and Washington, D.C., have outlawed foraging on public lands such as street rights-of-way and municipal parks.

It’s not allowed in New York City, although guerrilla foragers are common in Central Park. So, it’s always suggested to check local foraging laws wherever you are. And where foraging on public lands is allowed, be sure to stay away from sensitive habitats, such as wetlands, and take no more than you can use in a single meal.

And the best approach, says Vorderbruggen, is an even more hyper-local strategy. “Start in your own yard and in your own neighborhood,” he says. “Begin at your doorstep and identify the plants you see every day, and you will be amazed at what’s edible.” Then move out from your own yard to your neighbors’ yards.

When you walk the dog or ride a bike, figure out what plants look interesting, and you’ll likely see a few that can find a place on your plate.

“This is so much easier than pulling out an identification guide and looking for a particular plant,” Vorderbruggen says. And you sidestep any regulations on plant collecting when you forage on lands nearby. “Just ask a neighbor, ‘Hey, do you mind if I weed your lawn?’” Vorderbruggen laughs. “And then tell them what you find. People just can’t believe all the food that’s right there in the front yard.”

We have all heard the Chinese proverb: Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day; teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime. What if plan sponsors thought of retirement planning for their employees along the same lines?

Don’t get me wrong. The powerhouse trio that makes up the retirement auto-revolution—automatic enrollment, automatic escalation, and the widespread use of target date funds in the qualified default investment alternative (QDIA) slot—has had a positive impact on savings behavior, investment diversification, and potential participant outcomes. But even after the auto-retirement boom, the main concerns affecting defined contribution retirement plans remain largely the same.

In fact, plan sponsors may be lulling their participants into a false sense of security.

“Automated features only go so far if the plan falls short on adequately engaging participants with advice and education,” says Jennifer Doss, director of CAPTRUST’s Institutional Solutions Group. “The next step really does need to be reaching out to them one-on-one, educating them about what they have today, finding out what their goals and objectives are going forward, advising them on the right way to get there, and enacting change as needed.”

A Double-Edged Sword

While substantial progress has been made to help plan participants accumulate retirement savings, challenges remain. Participant inertia, which can work both in favor of and against participants and plan sponsors, continues to dominate as a top headwind for the retirement industry.

It was the 2006 passage of the Pension Protection Act (PPA) that spawned the auto-revolution. And just like that, the majority of defined contribution plan sponsors abandoned their 30-year ongoing battle against human inertia, choosing instead to embrace the powerful bias through the rapid expansion of auto-everything. The employees of these companies were suddenly able to start saving for retirement by simply doing nothing.

As they say, you have to take the good with the bad, and in this case, the downside of automatic features is participants commonly (and mistakenly) assuming their automatic retirement plan is good-to-go, as is, and doesn’t need anything else—no rebalancing, no asset-allocation review, no additional savings increases. The cruise control framework so helpful in overcoming inertia may actually be giving participants a false sense of security and, ironically leading them to pay less attention to their retirement accounts over time. Data bear this out.

According to Vanguard’s “How America Saves,” 92 percent of defined contribution plan participants did not initiate any exchanges within their accounts during 2017, and more than a third of participants surveyed in the report had zero contact with Vanguard during the year. This data tells us that participants are staying the course with their investment strategies—a good thing—but they are also not increasing their deferral rates or actively engaging in their plans—a concerning thing.

“What you see is that participants assume they’re saving and investing like they are supposed to, probably because their enrollment in the plan and their investment selections have been done for them. The setting of a savings rate and selection of an investment option by the plan sponsor creates this interesting endorsement effect with participants. Plan sponsors need to be aware that this perceived endorsement may actually serve to incent even more inertia,” says CAPTRUST’s Defined Contribution Practice Leader Scott Matheson.

Design to Win

“Too many plan sponsors are automatically enrolling employees at rates likely to result in inadequate retirement savings for many workers,” says Matheson.

Based on CAPTRUST independent research, just over half of all defined contribution retirement plans offer automatic enrollment—with 64 percent of those plans also offering the automatic escalation feature.

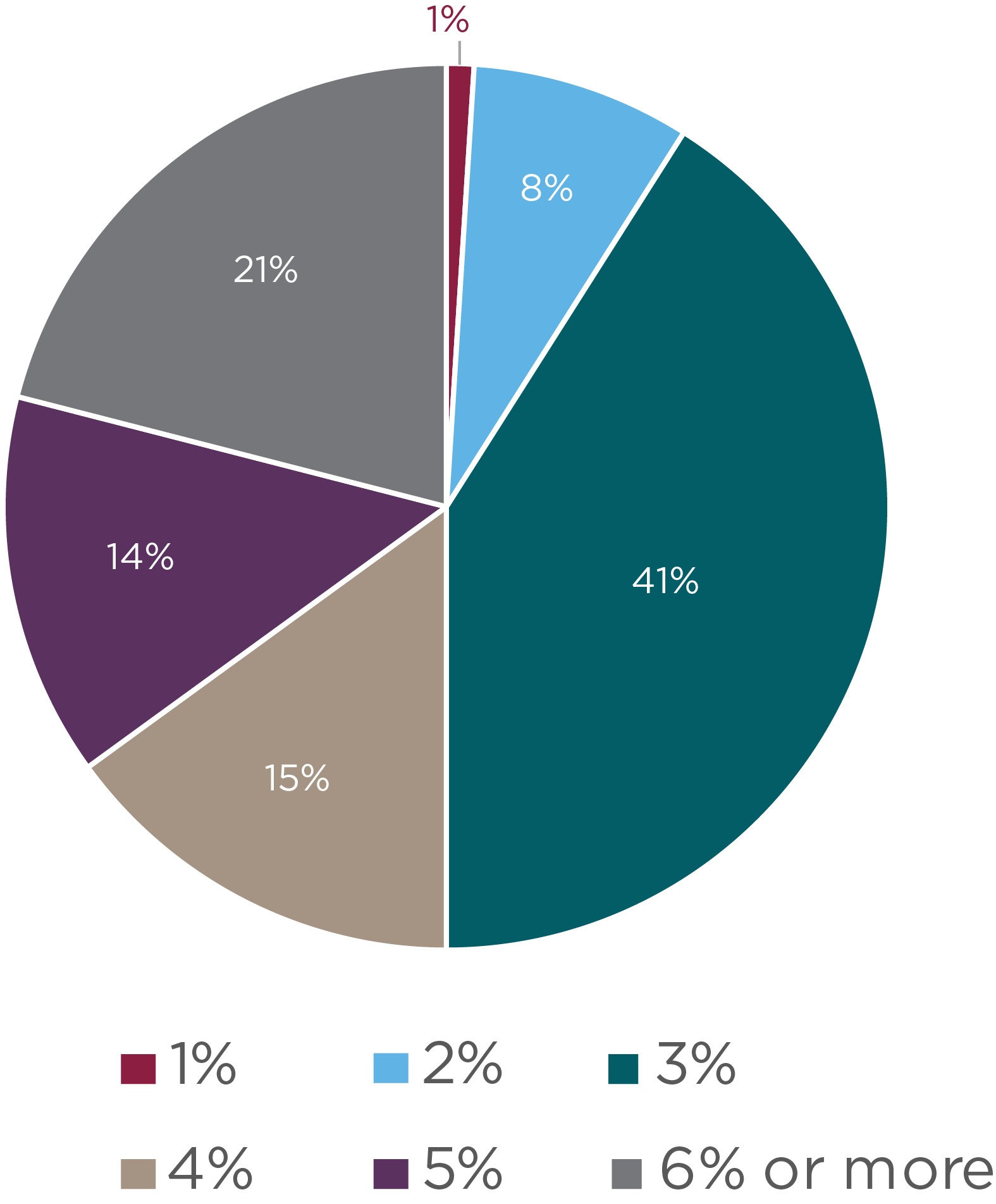

While experts recommend saving 10 to 15 percent of compensation, more than three-fourths of automatically enrolled participants are defaulted at a rate of 5 percent or less, as evidenced below, in Figure One. On average, that means three-fourths of participants in this population are not even saving at a rate of half the amount likely needed to allow them to replace their income in retirement. Further, half of participants surveyed were defaulted at 3 percent or less and only 1 in 5 participants reported a deferral rate of 10 percent or higher.[1]

Figure One: Default Automatic Enrollment Deferral Rates in 2017

“Most people see the initial contribution rate set by their employers as an endorsement of the right savings rate, such that it must be the appropriate amount to save for retirement. So why not harness human inertia and this perception of endorsement for yet another win and start people off at a rate that will more likely result in adequate savings for American workers?” says Matheson.

Studies show that plan sponsors fear upping their default contribution rates from the typical 3 percent because of concerns that it would negatively affect participation. However, the facts tell us this is not necessarily true.

Research from AARP concluded that higher default rates don’t dissuade participants. In fact, a company studied by AARP automatically enrolled participants at two different rates: 3 percent and 6 percent. The group offered the higher default rate had nearly the same level of plan participation—only a 5 percent difference.[2]

According to the same AARP research, a company surveyed with a 12 percent default contribution rate found that automatically enrolled participants stayed at this rate even though, in some cases, it resulted in savings that were higher than needed! In addition to illustrating the inelasticity of participant engagement to increases in the default savings rate, this type of behavior certainly validates the endorsement effect referred to by Matheson.

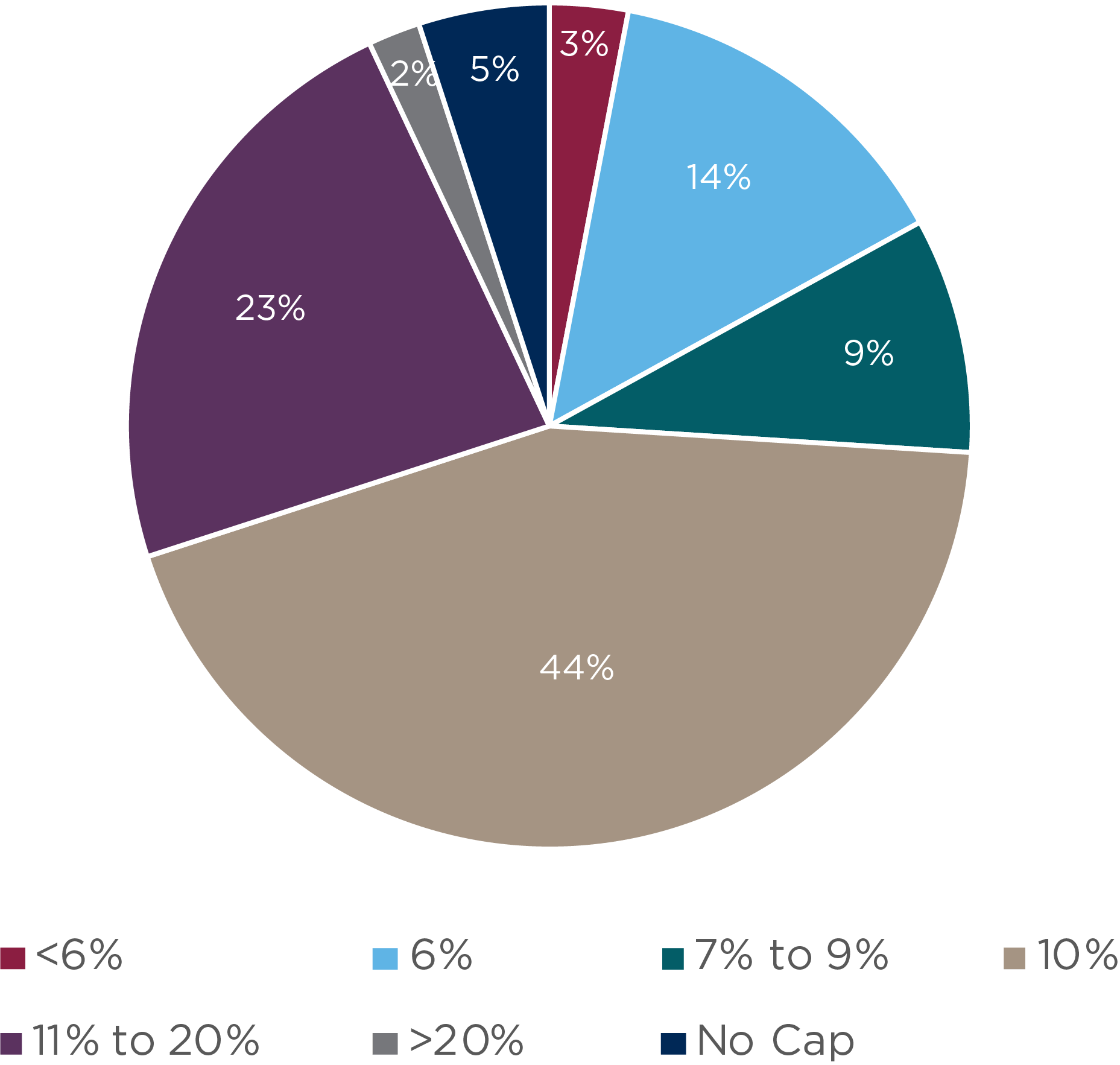

Figure Two provides a summary of default automatic escalation caps. The default escalation cap for defined contribution plans with automatic escalation is predominantly set to max out at the 10 percent IRS limit. Moreover, 26 percent of these plans capped increases at rates below 10 percent—below the recommended savings rate of 10 to 15 percent of pay.[3]

This also works against participants who want to make the smart move of contributing up to the maximum amount allowed under the 402(g) limits. Not so surprisingly, only 13 percent of participants reached the maximum amount of contributions allowable in 2018, which was $18,500 plus, catch-up contributions up to $6,000, for those age 50 or older. This year the Internal Revenue Service has increased the maximum employee 401(k) contribution limit to $19,000 per year, plus $6,000 in catch-up contributions.

Teach a Man to Fish

Figure Two: Default Automatic Escalation Caps in 2017

Whether participants go it alone or get the help of a financial advisor, taking time to slow down and focus on goals and make a plan is the first and most important step for plan participants.

Yet oftentimes, people are just overwhelmed. According to Allianz Life Insurance, more than 64 percent of Gen Xers—those between the ages of 35 and 48—say the lingering cloud of uncertainty that accompanies retirement planning keeps them from taking any action to help secure their financial futures.[4]

“Engagement is the key to success. But sometimes it’s partly about waiting for participants to reach a point, or experience an event, that makes them realize they need to start taking an active role in their financial future,” says Doss.

A recent analysis of 401(k) participants found that engaging in planning, either with a representative or using online tools, helped people identify opportunities to improve their plans and take action. And, roughly 40 percent of the people who took the time to look at their plans decided to make changes to their saving or investing strategies.[5]

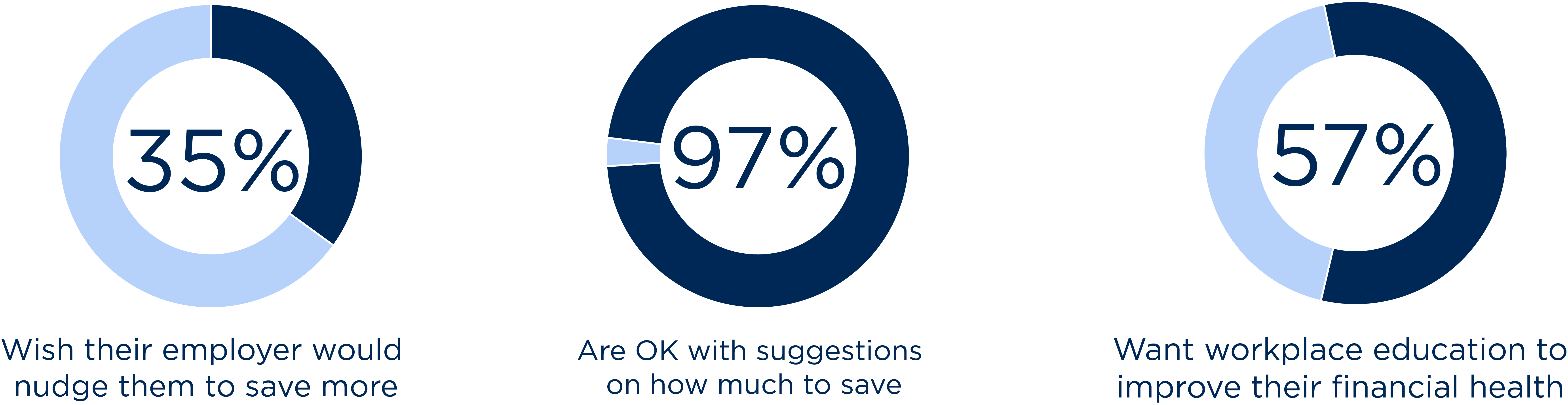

Plan sponsors may still be underplaying their role, however. The vast majority of retirement savers want to receive suggestions from their employer or plan sponsor on how much they should be putting away for retirement. According to recent research from Principal, shown in Figure Three, plan participant demand for workplace advice and education is high. More than half of employees would like workplace education that will help them improve their financial well-being, and 35 percent would welcome their employer to push them to save more.

Figure Three: Not Only Do Employees Need Help—They Want It and Are Asking for It

Source: “Is your retirement plan working?,” Principal, 2018

Boosting Financial Wellness

It isn’t only plan participants who lose out when they are not adequately engaged in their plans. Employers also feel the strain of a workforce burdened by financial stressors and uncertainty around retirement planning.

Gallup estimates the cost of America’s disengagement crisis at a staggering $300 billion in lost productivity annually. When people don’t care about their jobs or their employers, they don’t show up consistently, they produce less, or their work quality suffers.[6]

So, it should come as no surprise that an ever-growing number of plan sponsors are investing in ways to boost employee engagement. They are doing this through company-wide courses, lunch-and-learns, workshops, contests, and, most importantly, one-on-one advice.

Currently, 17 percent of large companies offer financial-wellness programs that incorporate online tools and 42 percent offer one-on-one consultations, up from 9.2 percent and 35.7 percent, respectively, in 2015, according to a recent benefit consulting firm study.[7]

It’s important for plan sponsors to understand that participants need and want to be nudged and reminded to engage in their plan.

“In my experience, the one thing that drives results the most is the one-on-one meetings because they’re completely customized,” says Doss. “I can’t overstate how important the interaction is with advice given specifically for that participant, specifically for where they are at in their life.”

Employers can ensure their workers are getting individualized information they can trust by partnering with third-party advisors, according to CAPTRUST Wealth Solutions Senior Manager Nick DeCenso, who says, “offering that kind of benefit sends a clear message to employees.”

“Working with a recordkeeper or an outside firm is one way for plan sponsors to show their employees that they take a serious interest in this,” says DeCenso. “Because most companies are not in the business of providing financial wellness advice to their employees, they’re in the business of something else.”

Keep On Nudging

Different channels of engagement, such as print communications, online tools, one-on-one meetings, or workshops can impact employees to varying degrees, and plan sponsors should strive to measure each method to determine effectiveness and make necessary changes.

A high-touch communication strategy built around milestones makes for a good way to get your participants attention, according to Matheson. “Consider sending targeted communications engaging participants to take an action. For example, a reminder to increase deferrals, timed to coincide with annual pay increases. The right message at the right time will drive positive participant behavior.”

Plan sponsors can stack the odds of success in the favor of participants by implementing automatic plan design features combined with comprehensive engagement-focused participant campaigns. This, along with technology enhancements, will move the dial forward, making it easier for plan sponsors to help participants mindfully reach their destinations.

Lastly, I’m not sure if just anyone can create a proverb, but I am going to try. Here goes. Enroll an employee at 3 percent and give them something that’s better than nothing; enroll an employee at 15 percent with immediate, engaging advice and education, and give them a dignified retirement.

[1] “How America Saves,” Vanguard, 2018

[2] John, David C., Shiflett, William R. “Higher Initial Contribution Levels in Automatic Enrollment Plans May Result in Greater Retirement Savings: A Review of the Evidence,” AARP Public Policy Institute, 2017

[3] “How America Saves,” Vanguard, 2018

[4] “Why Generation X Isn’t Planning for Their Retirement,” TheStreet, 2018

[5] “6 habits of successful investors,” Fidelity, 2019

[6] Amabile, Teresa, Kramer, Steven “Do Happier People Work Harder?,” The New York Times, 2011

[7] Tergesen, Anne, “401(k) or ATM? Automated Retirement Savings Prove Easy to Pluck Prematurely,” The Wall Street Journal, 2018

In February, CAPTRUST’s Cathy Seeber spoke to Financial Advisor magazine about substance use disorder. In the article, titled “Advisor Helps Clients Break Financial Drain Of Addiction”, Seeber shares that she, too, is the mother of a former heroin and alcohol addict.

The article calls out that, according to the National Institutes of Health, living in poverty is a risk factor for abuse of opioids and other substances. But Seeber wants readers to know that addiction doesn’t discriminate.

With growing numbers of high-net-worth families afflicted by the opioid epidemic, Seeber goes on to say, “It’s easier for wealthy individuals to continue to access legal opioids, and they’re better able to hide their addiction because it’s not as physically obvious as heroin, a less expensive substitute.”

Seeber comments how important it is to learn to recognize the signs, ask the right questions, and listen patiently if you suspect someone you care about has a problem with addiction.

To view the article in its entirety, please click here.

About CAPTRUST

CAPTRUST Financial Advisors is an independent investment research and fee-based advisory firm specializing in providing investment advisory services to retirement plan fiduciaries, endowments and foundations, executives, and high-net-worth individuals. Headquartered in Raleigh, North Carolina, the firm represents more than $313 billion in client assets with 38 offices located across the U.S.

When it comes to spending and investment policies, it’s a bit of a chicken-and-egg scenario for nonprofits. How a nonprofit chooses to invest portfolio assets and the amount of grants it plans to award are complimentary decisions, so it’s basically impossible to say which of these decisions comes first.

What we can say with certainty is that endowments and foundations need both an investment policy that documents how portfolio assets are deployed and a spending policy that outlines how much of the portfolio is earmarked for grants. We also know that stakeholders who do not tie spending to investments create significant potential for a decline in portfolio assets and the financial means to award grants in the future.

It should, therefore, come as no surprise that organizations that craft incompatible spending and investment policies may jeopardize a nonprofit’s future and may violate their fiduciary duties under the Uniform Prudent Management of Institutional Funds Act (UPMIFA). In fact, UPMIFA specifically indicates that organizations must factor in the investment policy of the institution and the expected total return from income and the appreciation of investments when determining spending rates.

Successfully fulfilling the mission of a nonprofit depends on careful control and planning around both spending policy and investment strategy.

The Role of a Spending Policy

An organization’s spending policy is a tool that guides the charitable spending and investment trade-off. Spending rules are ultimately designed to advance the mission of an organization and its multiple goals. “A nonprofit institution’s spending approach should be unique to the goals, financials, and risk profile of the organization; it’s not a one-size-fits-all approach,” says CAPTRUST Senior Manager James Stenstrom.

“Our experience has shown us that having clearly defined spending rules instills a higher level of accountability into the budgeting and financial oversight process,” says Stenstrom.

Developing an appropriate spending policy is one of the more challenging steps in the nonprofit planning process. “The institution’s spending policy is usually one of the most important investment strategy inputs,” says Stenstrom. Interestingly, as shown in Figure One, 12 percent of CAPTRUST’s 2018 Endowment and Foundation Survey respondents do not have a formal documented spending policy.

Figure One: Endowments and Foundations with a Documented Spending Policy

Source: CAPTRUST’s 2018 Endowment and Foundation Survey results.

However, a poorly understood or implemented spending policy may be worse than not having one at all. It is important to have an established spending policy in good order and accessible to key decision makers. Furthermore, decisions about implementing a spending policy should be formally documented so context is maintained as stakeholders change over time.

A formal spending policy is an important component of any audit trail. It provides the context necessary to understand drivers of past success or failure. Lastly, a formal policy accompanied by documented compliance may be the best defense against the potential for declined ability to award grants for future generations.

The Big Balance

For key decision makers, balancing current and future spending can involve difficult, even painful, trade-offs. Officials must balance the expected life of the programs to be funded against the desired life of the organization and the intent of the original charitable gift. This involves the management of three broad trade-offs: spending, investment risk, and investment return.

There are no easy answers.

“Nonprofits must carefully orchestrate the trade-offs between sustainability and predictability in the present and the future. The more a spending policy varies with fluctuations in asset values, the more sustainable—but less predictable—it is,” says CAPTRUST’s Stenstrom.

A high rate of spending requires a relatively aggressive and riskier portfolio or more fundraising to support that spending. Conversely, committees that prefer more conservative investment approaches may need to reduce spending. Stenstrom explains that the spending rate should be coordinated with overall average portfolio returns to ensure spending and investment returns are well balanced.

“Spending more than generated returns on an ongoing basis is a recipe for a decline in assets, regardless of other features of the spending rule,” says Stenstrom. “The perpetual struggle is to decide how much of the available assets should go to those worthy causes currently knocking at the door and what should be invested for future needs.”

When endowments and foundations invest too aggressively, their portfolios may be decimated by both spending and portfolio declines. But if they invest too conservatively, their portfolios may not provide enough growth to keep up with inflation. High levels of spending may require aggressive investment strategies, but these strategies may lead to greater uncertainty in returns, making a spending policy less sustainable.

Given these uncertainties, it’s in the best interest of nonprofits to carefully coordinate overall fund goals with spending and investment decisions. Further, it is critical that decision makers understand the impact that spending decisions can have on their investment portfolio.

Different Types of Spending Policies

An endowment or foundation’s spending policy might be based on current asset value, trailing-average asset value, past spending, income from assets, portfolio returns, or some combination of these. But the right spending policy plays a significant role in an institutions’ ability to achieve its objectives.

A well-thought-out spending policy should balance the current and future needs of the organization while creating a practical and predictable level of spending. A sound policy must also consider the organization’s other sources of funds, such as fundraising, grants, and government support, and how they correlate to the financial markets and spending needs. And finally, a good spending policy maintains the original donor’s intent where applicable.

Evaluating strategies across multiyear market scenarios allows more flexibility in the types of spending policies that can be considered and provides the ability to emphasize different goals over different investment horizons.

“Most often, we see moving-average-based spending policies—where an organization spends a fixed percentage of its portfolio’s average market value over a set time period,” says CAPTRUST Senior Director Grant Verhaeghe. “12 or 20 quarters are commonly used periods.”

But while moving average policies tend to strike a good balance between preserving portfolios and sustaining future spending, we see nonprofits using a variety of spending policy types as shown in Figure Two.

Figure Two: Spending Policy Usage Among Nonprofits

Source: CAPTRUST’s 2018 Endowment and Foundation Survey results.

There is no way to conclude if one policy is superior to any other policy on a general basis, since each has its merits in different situations.

A thorough review of a nonprofit’s goals, objectives, and needs is a staple in both the initial and ongoing part of establishing your nonprofits spending policy. As the decisions made around spending help drive asset allocation and investment manager selection decisions, establishing these rules can be one of the most important and pressing choices a nonprofit board, spending, or investment committee will make.

Excuse Me, Young Brother, I Just Did

In the late 1960s, Eddie Joseph was a high school honor student, slated to graduate early and begin college. That path took a detour. A long one. Impassioned to resolve the social, economic, and political wrongs he saw in his Bronx community and the nation, 15-year-old Eddie was drawn to the ideology of the Black Panther Party, which was just gaining a national presence.

He remembers riding the subway to the Panther office in Harlem with two friends to offer his services, enraged by the recent assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. He was ready to fight, even kill if necessary, to serve the cause.

At the Panther office, a leader called the earnest teen up front. As Joseph stood by his side, the leader pulled open a desk drawer and reached far into it. Joseph’s heart pounded. He was prepared to be handed a gun—the power for social change.

Instead, he was handed a stack of books, such as The Autobiography of Malcolm X and The Wretched of the Earth, Frantz Fanon’s 1961 work on the cultural foundations of social movements. Taken aback, Joseph said, “Excuse me, brother, I thought you were going to arm me.” The Panther’s reply: “Excuse me, young brother, I just did.”

By 16, Eddie—now called Jamal—learned that the militant group the FBI declared to be “the greatest threat to America” was a multifaceted entity. The Party’s 10-point program called for fair housing, education, justice, and peace. They put those ideals into action with free breakfasts for school children. Free medical clinics for those who could otherwise not afford health care. Neighborhood patrols to protect citizens threatened by street violence and police brutality. The guns were just there to establish authority and prevent law enforcement obstruction to the primary mission: liberation.

“Freedom and liberation are really abstract concepts,” says Joseph a half century later, speaking with a temperate grace that belies the radical fervor of his younger self. What it means depends on where you are on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. “To a person who is hungry, freedom is a meal. To someone who is homeless and cold, liberation is a safe, warm, dry place to sleep. To a person who is sick, political power is a doctor, nurse, and medicine. So, in a day in the Panther Party, you probably saw or touched a gun 5 percent of the time, but spent 95 percent of the time working in the community.”

The Panthers Joseph saw organizing free services in their communities stood in striking contrast to the menacing, gun-toting criminals he saw on television. He saw that true empowerment is not the product of violence but of empathy.

Joseph has carried with him a lifelong lesson from the late Afeni Shakur, a fellow Panther and big sister figure. “She said, ‘You know Jamal, the real goal of the Panther Party is not to have every person in Harlem or the black community become a member of the Black Panther Party. The goal of the Panther Party is to lead by example and show the people the possibilities of struggle for emancipation and liberation—to lead by possibility and to make ourselves obsolete.’”

“Imagine that pearl of wisdom on a 15-year-old kid,” Joseph says. “If you think you’re going to be a Panther, know that real leadership and service is to make yourself obsolete because the people are empowered because they get it, and they get it for them.”

Serve the Time, or Let the Time Serve You

If violence did not top the Black Panther Party’s tenets, it was undeniably part of the implementation. By 16, Joseph’s devotion to the cause landed him in prison on infamous Rikers Island, charged with a bombing conspiracy as part of the Panther 21 in one of the most emblematic criminal cases of the 60s. When exonerated, he became the youngest spokesperson and leader in the Panthers’ New York chapter. In one of his more renowned oratories, he urged Vietnam war protestors to burn down the Columbia University campus.

He later landed back in prison, sentenced to 12 years in Leavenworth for harboring a fugitive in an armed robbery. Despite the dangers and despair of life in a federal penitentiary, Joseph credits this time for resetting his life’s compass.

“An older prisoner, Mr. Cody, gave me life-changing advice,” Joseph recalls. “He said, ‘Young blood, let me tell you some-thing. You can serve this here time, or you can let this here time serve you.” As Malcolm X said, ‘The penitentiary has been the university for many a black man.’”

While in prison, Joseph earned college degrees with honors in psychology and sociology, wrote poetry and his first play, and founded a groundbreaking theater company that brought together prisoners formerly divided by race, culture, and violence.

Joseph didn’t start out with the idea to develop a theater company. Some inmates—most notably Mr. Cody—challenged him to do a play for Black History Month. “I couldn’t find anything in the library, so I wrote a play and had black brothers rehearsing,” Joseph recalls. Parole by Death was based on the true story of a young prisoner stabbed to death two weeks before his parole date.

“Then some Latinos showed up to a rehearsal,” Joseph says. “We thought something must be really upsetting them. One came up and said, ‘I’ve got to talk to you.’ I thought, oh damn, it’s me. He said, ‘I’ve been watching this for about 10 minutes, and that guy, he’s not feeling his character.’ So I rewrote the play to include Latino characters. Then some white brothers showed up and wanted to be in the play, so we ended up having this multicultural experience.”

“These were groups that stood in different areas of the yard in the voluntary segregation that happens in prison. You stay in your own section of the yard. I thought, this is amazing.” This cultural bridge epitomized the Black Panther Party’s slogan of “power to all the people” across racial lines. There were just 12 to 15 men in the play, but more than 2,000 in the audience giving them a standing ovation, a profoundly unifying moment.

“I saw men change, not only in how they communicated with each other, but in starting to realize that they could act, they could write, they could sing. They wrote letters home, poetry. I saw the transformative and healing power of the arts, and I started thinking this was the work that I wanted to do.”

“I was still a prisoner, but I’d found a new kind of freedom.”

From Prison to a War Zone

Released from prison on Christmas Eve 1987, Joseph returned to a Harlem that looked like the aftermath of a World War II bombing raid—block after block of devastation and decay, punctuated by nightly gunfire at the height of the crack epidemic. He had a family to consider: his wife, Joyce Walker, an actress and model who was the first African-American woman on the cover of Seventeenmagazine, and his young son, Jamal Jr. It would have been so easy to leave. Go somewhere safe.

Instead he stayed and tapped the social activism that had drawn him to the Panthers decades earlier. He immersed himself in projects and making ends meet. On his résumé he listed his Black Panther affiliation and time in prison under “Other Experience.” His candor and street cred earned him a role at the Harlem campus of Touro College, where he worked seven years as a counselor, professor, and director of student activities.

From there, he accepted an invitation to teach a semester of screenwriting at Columbia University, which led to another, then a steady climb up the academic ranks to full professor and a five-year term as chair of the film school. As the first African-American head of any department in the school of the arts, Joseph worked to increase diversity of thought and perspective, both in the faculty and student body.

In the midst of his ascent at Columbia, Joseph’s life took another turn. A 16-year-old neighbor was killed at a party. The boy had confronted a young gunslinger who had disrespected his sister. The youth shot him.

“When Andre’s mother received the news, her apartment was too small to contain her grief,” Joseph recalls. “She ran out into the street and wailed.” Joseph was still mourning the death of his godson, Afeni Shakur’s son, Tupac, who had been killed in Las Vegas a year earlier.

The what-ifs haunted him. Was there more he could have said or done for Tupac? For Andre? “I was helping run a youth program in Manhattan. Why not in Harlem, where I live, I thought? If Andre, or the boy who shot him, were in a creative arts workshop instead of out partying or doing drugs on the street, then maybe Andre would still be alive. These pointless deaths had to stop. I knew I had to do something. And I knew what my weapons would be.”

Making an Impact

Joseph approached Voza Rivers, executive producer of Harlem’s New Heritage Theatre, with a vision to bring arts to Harlem youth, to create a refuge from the streets and help kids make sense of their world.

The IMPACT Repertory Theatre began in a community center basement with nine students—including Joseph’s three children. Within a year, 75 kids had joined. Since then, more than 2,000 young people have been part of IMPACT in New York. Of those who stayed with IMPACT through high school, 75 percent have gone on to college. Thousands more have participated in IMPACT-led workshops in New York, Philadelphia, and Atlanta.

The repertory company performs in front of more than 25,000 people a year at venues ranging from the United Nations headquarters to New York City Hall, hospitals, public schools, and, yes, penitentiaries.

More than a performing arts troupe, IMPACT is based on a mission statement of SOS—safe space, outstanding effort, and service to family, friends, and community. Prospective members go through an intensive 12-week boot camp where they learn the fundamentals of leadership, service, and public speaking—and forge indelible connections.

IMPACT members visit nursing homes, clean up city blocks, and organize food and clothing drives. They serve meals, participate in sharing circles with elders, register voters, and fundraise for charity. “We teach young people that they can be socially active and make a difference,” Joseph says. “There’s no start date for activism, and there’s no expiration date for your dreams.”

Young people audition for the program, but it’s not a pass-or-fail proposition. It’s a chance to find each one’s best niche. Will this person dance, sing, write, or work as a stage manager behind the scenes? “We know we can’t get every kid on stage, but we sure want to get every kid to college,” says Joseph. “If we can teach not only creativity but community and commitment, then we will help them become better people. If they become better singers, dancers, or writers, that’s great, we’re cool, but if you’re a mediocre singer, dancer, or writer but you become a better person, then we’ve done our job, and you will see us jumping for joy.”

The kids write or co-write their own material and choreography, and Joseph is very vested in them. He gets choked up and a little teary-eyed watching them perform, whether in the borrowed rehearsal space or on stage at the 2008 Academy Awards, telecast to a billion viewers. “The kids say, ‘Are you okay Uncle Jamal?’ I say, ‘I have some allergies.’ I’m good at allergies.”

An Enduring Legacy

Alumni from the program come back to share their stories. Now in their 20s and 30s, they are educators and social workers, professionals in medicine, law, and arts management. Many have graduate degrees. Two are PhD candidates.

Count Joseph’s own children in that number. Eldest son Jamal, 36, has a Master of Fine Arts in film from Columbia. Middle son Jad, 30, a Brown University graduate and activist, is passionate about restorative justice and campaigns for progressive candidates. Daughter Jindai, 27, a Columbia University grad, is director of operations and creative producer at a Harlem-based advertising and marketing firm as well as a talented musician. All three were IMPACT kids.

From Revolutionary Artistic Activism

In addition to creating IMPACT and inspiring a generation of Columbia students to tell their stories in film, Joseph is a wellspring of creativity. He published Tupac Shakur Legacy, a biography of his godson, and the autobiographical Panther Baby. He was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Song in 2008 for a song he co-wrote for the film August Rush.

He is co-founder and faculty advisor of FOCUS—Filmmakers of Color United in Spirit—which promotes diversity and inclusion in community work, mentoring, and storytelling through film.

He is working on Peace Warriors, a musical about anti-bullying and anti-violence that has original monologues, poetry, music, and dance by IMPACT members. A documentary on a Harlem-based civil rights lawyer is in the works. So is a television series based on Panther Baby.

Joseph’s critically acclaimed 2017 film, Chapter & Verse, tells the story of a reformed gang leader who struggles to adapt to a changed Harlem after serving an eight-year prison sentence. “I’m very proud of the film as a filmmaker because I was able to artistically make a film that people appreciate.”

Chapter & Verse represented the perfect confluence of Joseph’s worlds. It showcases the talents of present and former Columbia students and IMPACT kids in front of and behind the camera. Joseph is shooting film, not bullets, in Harlem to tell a story that personally resonates—how to find hope and relearn the joys of life and living, “despite an outwardly bedeviled society.”

Now Joseph is raising funds for his next dream—a space in Harlem so IMPACT can have a permanent home and expand offerings with its own dance space, theater space, recording studio, and multimedia center to create digitally enhanced stage experiences. It’s a natural extension of the community-based social activism he learned decades ago as a Panther. “We knew back then that we had bright minds questioning the world,” he says. “Now I want to create a space for the best and the brightest minds of this generation.”

Even with his career and community successes, Joseph can hardly believe he has been at Columbia University for 20 years. He came in thinking he was going to teach one course for one semester. He was stunned to be asked back for a second semester.

“I’m reminded of the irony of this turn of events whenever I walk by the large statue of Alma Mater that stands in front of the Low Library in the middle of the Columbia campus,” Joseph says. “She looks down at me with a look that says, So it’s Professor Joseph now, huh? I remember when you were a young Panther, and all you wanted to do was burn this damn place down or die trying. Well, we both survived, and here we are. Maybe there’s a future after all.”

Just about everything in the sprawling 91-year-old Dutch colonial in Bexley, Ohio, is, in fact, there by design—and part of an experiment in four-generation living Lisa Cini and her family launched in 2014.

Cini, who specializes in designing senior living facilities, used her talents to create an unglamorous but functional 4,300-square-foot home for herself, her husband, and their then-teenaged children to share with her parents and her maternal grandmother, then 92.

Cini’s grandmother, Gerline Lilly, passed away recently from Alzheimer’s disease at age 96. “She lived a phenomenal life and at the end, got to live with my kids, and my mom and dad, and us,” Cini says. “We’ve all benefited.”

Cini describes the experiment in her book Hive: The Simple Guide to Multigenerational Living. It’s an experiment that, in one form or another, more of us are trying.

A New Multigenerational Normal

A record 64 million Americans—20 percent of the population—lived in multigenerational homes in 2016, according to the Pew Research Center. The count includes young adults living with their parents, elders living with their grown children, and grandparents living with grandchildren.

Such households are, of course, common around the world. They are part of our history, too. In 1940, more than two-thirds of people over age 85 lived with extended families, as did one-third of adults ages 25 to 29, according to Pew.

But those numbers plunged after World War II, as a housing and economic boom normalized the nuclear family home. Young adults were expected to set up their own households as quickly as possible, and elders were expected to live independently or among their peers, in senior communities, assisted living facilities, and the like. By 1980, just 12 percent of Americans lived in multigenerational homes.

But during the Great Recession a decade ago, multigenerational living surged back. And it shows no sign of receding now, despite the improved economy, experts say.

In many cases, “people may have come together by need, but they’ve stayed together by choice,” says Donna Butts, executive director of Generations United, an advocacy group that works to strengthen intergenerational connections.

Along the way, she says, attitudes toward such families have changed. Stories about beleaguered baby boomers unable to rid themselves of boomerang kids and needy elders have increasingly given way to more positive narratives, she says, about families choosing to live with and care for one another.

For people who choose the multigenerational lifestyle, “it’s not a sign of weakness,” Butts says. “It’s really a sign of strength for people to admit they enjoy being together. For many families, it’s really a wonderful thing.”

Cini says there may still be some stigma—or fear of stigma—attached to setting up a multigenerational home.

“After I did this, people would come up and say, ‘I want to do this too,’ but it was almost like a dirty little secret,” she says. In the case of people taking in aging parents, she says, “part of it was that they didn’t want people to think they couldn’t afford to put their parents somewhere else.”

And, for many families, financial considerations do still play a role in decisions to double or triple up—even if they are doing it in gleaming new homes or smartly repurposed or remodeled digs, some experts say.

In the San Francisco area, young adults are coming back to live with their parents not because they cannot find jobs, but because their perfectly respectable jobs do not pay enough to cover the high costs of housing there, says Fran Halperin, a Bay Area architect specializing in accessibility and aging in place.

For some, “there’s a lack of confidence that the economy will stay good. I hear a lot of people referring to the next recession,” says Joanne Theunissen, chair of the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB). Theunissen builds and remodels homes in and around Mount Pleasant, Michigan.

That kind of thinking, she says, leads clients to think about how to get the most from their homes—which means thinking about their extended families’ needs in the future.

“I’m building a house right now for a single woman with a daughter,” she says. “Her daughter is in college. Her parents live in Ohio. But she wants a suite for her parents to come and live in in the next few years and another room for her daughter when she comes home.”

New Kinds of Homes

The multigenerational living trend has created a market for new homes built expressly for shared lives. Lennar, the nation’s largest homebuilder, has for the past several years offered a line of what it calls Next Gen® homes—homes designed with attached one-bedroom units that have their own entrances, kitchenettes, and parking but can open into the main house.

Promotional videos at the builder’s website show the sorts of families the homes might attract. There’s a family with a grandmother and another with a developmentally disabled adult daughter, each living semi-independently in their attached suites.

Of course, not everyone plans ahead for multigenerational living.

“Often, there’s some kind of family crisis. Grandma falls and breaks a hip or junior loses his job and has to move back in with the family,” says Northern California remodeler Michael Litchfield, author of In-Laws, Outlaws, and Granny Flats: Your Guide to Turning One House into Two Homes.

Such renovations are the solutions that many families seek if they have the resources. Those resources include not only money, but a house and lot that can accommodate added rooms, ideally with their own entrances, cooking and bathing facilities, and outdoor spaces, Litchfield says.