-

Solutions

- Solutions

-

Individuals & Families

- Individuals & Families

- Individual Investors

- Executives & Business Owners

- Families with Complex Needs

- Professional Athletes

-

Retirement Plan Sponsors

- Retirement Plan Sponsors

- Corporations

- Educational Institutions

- Healthcare Organizations

- Nonprofits

- Government Entities

- Endowment & Foundation Leaders

- See All Solutions

Comprehensive wealth planning and investment advice, tailored to your unique needs and goals.Investment advisory and co-fiduciary services that help you deliver more effective total retirement solutions.CAPTRUST provides investment, fiduciary, and risk management services for nonprofit organizations. -

About Us

- About Us

- Our People

- Our Story

- Learn About CAPTRUST

-

Locations

-

Resources

- Resources

- Articles

- Podcasts

- Videos

- Webinars

- See All Resources

Originally, the DOL had intended to gather the necessary information for this database from IRS Form 8955-SSA, since that form already captures the data needed. However, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) does not believe it is allowed to share form 8955-SSA data with the DOL.

In the proposed procedure, the DOL places the burden of data collection and reporting on plan administrators. Administrators would be required to provide necessary data to the DOL via Form 5500s each year, perhaps starting with the 2023 5500s that are due in 2024. Because, for most plans, the collection of 5500 data is almost always outsourced to a third-party administrator (TPA) or bundled recordkeeper, these will be the entities that would presumably provide required data to the DOL via the 5500s of the individual plan sponsors.

The DOL is asking plans to provide the following for vested separated participants:

- Names and Social Security numbers,

- Contact information,

- Mailing addresses,

- Information about whether they have received an involuntary distribution already, and

- Information about the participants’ designated beneficiaries.

Plans must also indicate if a participant has been unresponsive to contact.

At first glance, the reliance on voluntary data collection from plan administrators via a highly segmented process such as that that exists around Form 5500s appears to be administratively difficult. The comment period for this proposal is open until June 17, 2024, and is expected to receive pushback from many organizations in the retirement plan industry.

Interest rates have a similar effect on economies. When financing costs rise, business decisions about new projects, growth, and expansion become more complex—and risky. For consumers, big-ticket purchases become more expensive. Across the economy, higher interest rates can cause a broad slowdown as individuals try to conserve energy for the uphill climb. This is why interest rates are such a powerful monetary policy tool for combating inflation.

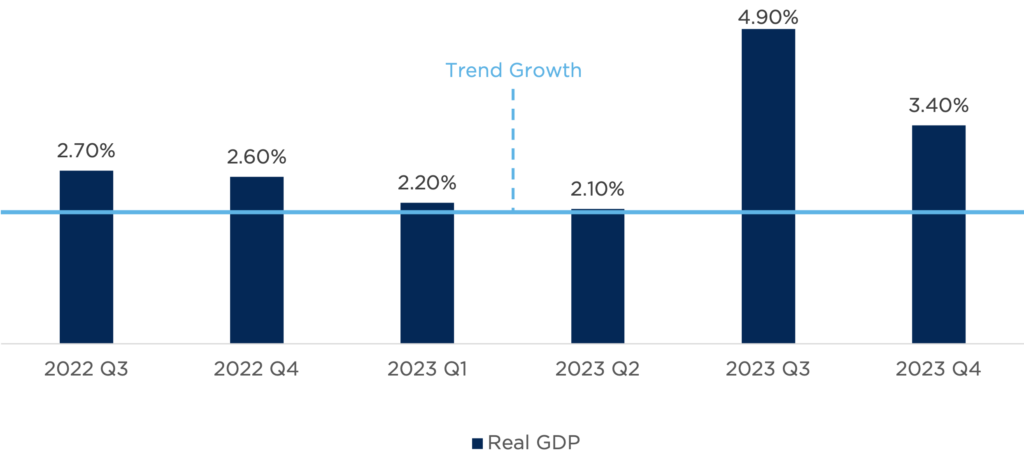

However, despite the Federal Reserve’s aggressive rate-hiking campaign over the past two years, the U.S. economy has not only maintained its pace on the uphill climb—it has accelerated. As shown in Figure One, real gross domestic product (GDP), the combined output of the U.S. economy, grew at an annual rate of 3.4 percent during the fourth quarter of 2023, easily outpacing the trend growth rate over the past 20 years of approximately 2 percent.

Figure One: Real GDP and Long-Term Trend Growth

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, CAPTRUST Research. Trend growth represents the average, seasonally adjusted annual growth rate over the past 20 years.

The stock market has likewise continued to climb, with the S&P 500 Index closing the first quarter of 2024 at an all-time high, surpassing its previous high-water marks 22 times during the quarter. What’s also impressive is the consistency of the ascent, with the index marking 277 consecutive trading days without a one-day decline of 2 percent or more.

So far, the U.S. has demonstrated economic athleticism in the face of rising rates. But with expectations now favoring a higher-for-longer scenario, with a Fed that is in no hurry to reduce interest rates in the face of sticky inflation, investors must consider whether the economy is strong enough to sprint across the finish line, or if its legs risk giving out just short of the goal.

Market Rewind: First Quarter 2024

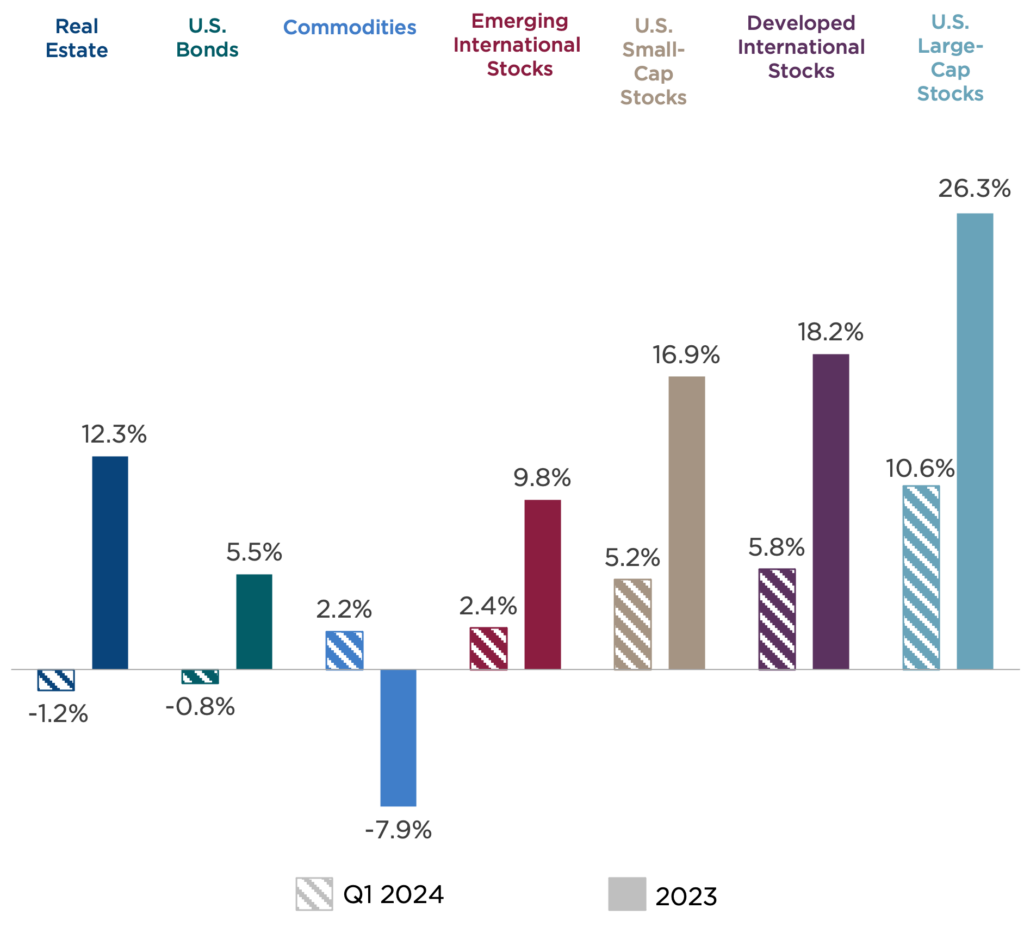

U.S. large-cap equities continued to power higher during the first quarter. The S&P 500 returned 10.6 percent, its best start since 2019, driving the one-year trailing return of the index to nearly 30 percent. All S&P sectors but one were positive. Those most closely aligned with the artificial intelligence (AI) boom continued to lead the market, including communication services and technology, which delivered returns of 15.8 percent and 12.7 percent, respectively.

Despite the continued strength of these sectors, markets also displayed a healthy expansion of participation during the first quarter. The much-talked-about Magnificent Seven mega-cap technology stocks were responsible for 60 percent of index returns in 2023, but their contributions fell to about 20 percent of index performance in March. Contributions from a broader swath of stocks is considered a sign of health in equity markets.

Figure Two: First Quarter 2024 Market Recap [1]

Value-oriented sectors, including financials, industrials, and energy, showed strength as well. In stark contrast to its lagging results during the fourth quarter of 2023, the energy sector showed a healthy return of 13.7 percent as oil prices rallied on strong demand expectations, supply constraints, and continued geopolitical concerns.

U.S. small-cap stocks rallied late in the quarter to erase their early losses and deliver a return of 5.2 percent. This represents a continuation of a three-year trend of underperformance relative to large- cap stocks. Investors continued to prefer mega-cap technology firms with higher profitability and showed a preference for less interest-rate-sensitive corners of the market.

Growth conditions also improved outside the U.S. during the quarter, with various sentiment and economic activity indicators on the rise. International developed market stocks returned 5.9 percent. Their emerging market counterparts trailed with a 2.4 percent return as the Chinese economy continued to face headwinds. Returns were particularly strong in Japan, where market-friendly regulatory reform pushed the Nikkei index past its all-time high, set more than 30 years ago.

The bond market proved less sanguine about the prospect of higher-for-longer interest rates. The yield on the 10-year Treasury climbed from 3.9 to 4.2 percent, leading to slightly negative returns for core bonds, along with higher mortgage rates and borrowing costs. Corporate credit spreads continued to tighten during the quarter, offering investors little incremental compensation for taking credit risk.

Gaining Momentum

Given the powerful impact that interest rates have on the economy and financial markets, it’s no surprise that the rapid rise of the federal funds rate in 2022 coincided with the largest stock market selloff since 2008’s global financial crisis. Since then, however, markets have shown remarkable tenacity.

Several strong tailwinds have supported economic resilience in the face of high and plateauing interest rates, including robust consumer spending, a healthy but not overheating labor market, strong expectations for corporate earnings, election year fiscal support, and optimism for an AI-driven productivity boom.

Consumer Spending

Consumer spending, which grew at an inflation-adjusted rate of 3 percent in the fourth quarter, was the largest contributor to the stronger-than-expected GDP growth at the end of that year. Consumers continued to spend despite ongoing inflation fatigue and higher debt servicing costs. This is largely due to the purchasing power provided by after-inflation wage increases.

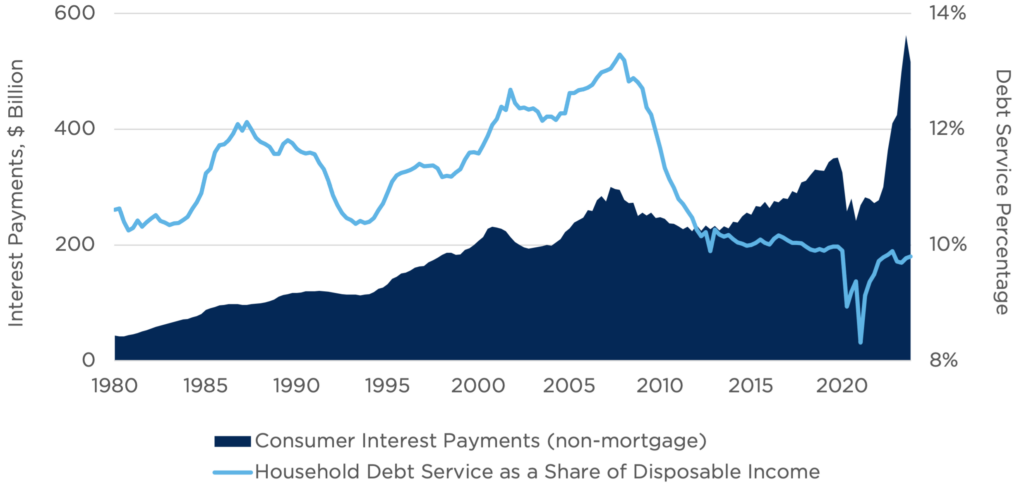

Consumers were also more reliant on credit to fund purchases, with credit card balances rising by 13 percent, even as credit card interest rates reached 30-year highs, according to Federal Reserve data. As shown in Figure Three, the result was a spike in the amount of non-mortgage interest paid by U.S. consumers. However, the increase was more than offset by rising real wages, allowing overall debt servicing costs to remain well below historical averages. This suggests that the tailwind of consumer spending may have more room to run.

Figure Three: Consumer Interest Payments and Share of Disposable Income

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Labor Market

A robust labor market underpins the continued strength of consumer activity. The non-farm payroll jobs report presented a pleasant surprise in March, with the economy adding 303,000 jobs versus an expected 214,000. This degree of outperformance caught even the most bullish economists off guard. The unemployment rate fell to 3.8 percent, marking the 26th straight month that unemployment has remained below 4 percent.

The report was overwhelmingly positive. Still, there were subtle clues that momentum may be slowing. Employment in non-cyclical sectors, such as health care and education, was a larger driver of job growth than employment in more cyclical and economically sensitive sectors. Also, temporary employment declined, another potential indicator of future weakness. The ratio of job openings to unemployed workers continued to soften from its 2022 peak, and the quits rate remained at its lowest level since 2020, indicating that workers left jobs at a slower pace.

Earnings Growth

In 2023, equity market returns were closely tied to interest rate-cut expectations, and price gains came mostly from the expansion of price-to-earnings (P/E) multiples. Even with a strong fourth quarter, when S&P 500 earnings grew at a rate of nearly 4 percent on a year-over-year basis, calendar year 2023 earnings growth for the index was essentially flat, even as the S&P 500 returned more than 26 percent.

With a forward P/E ratio near 21 for the S&P 500, stock market valuations are expensive by historical standards, and returns from here will rely more on earnings growth than valuation multiple expansion. This represents a potential inflection point for equity investors as fundamentals come into greater focus. It also offers the potential for a lower degree of market concentration if businesses of all shapes and sizes are rewarded for strong financial results.

Expectations for 2024 earnings are robust, with analysts forecasting approximately 11 percent growth for the year. Corporate balance sheets are healthy, with high levels of cash as businesses prepared for a 2023 recession that never materialized. This excess cash now represents dry powder that could be deployed for investment and expansion or returned to shareholders. It could also provide a liquidity buffer in the event of a negative economic surprise.

Fiscal Support and Election-Year Dynamics

Another potential tailwind for markets this year is fiscal support from the federal government. This could come from both the continued rollout of already-enacted programs and election-year influences.

A range of in-process government programs will continue to provide economic support, including additional grants from the CHIPS and Science Act, the resumption of the Employment Retention Credit program, and student loan forgiveness. Restocking depleted weapons stockpiles will also create a tailwind for defense-related companies.

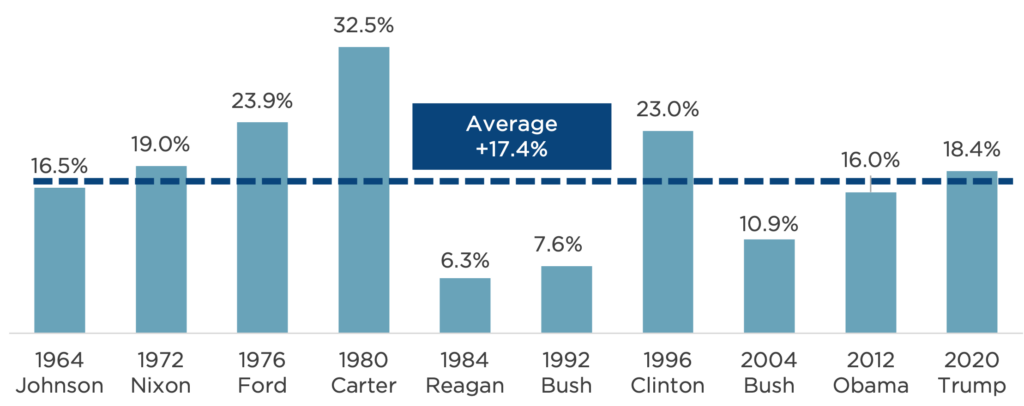

Federal election years have historically been favorable for markets, particularly when incumbent presidents are running for reelection. The economy is a consistent, top-of-mind issue for voters, encouraging market-friendly policy actions. As shown in Figure Four, the S&P 500 has ended the last 10 election years with an incumbent running for reelection in positive territory, with an average return of 17.4 percent.

Figure Four: S&P 500 Election Year Returns with Incumbents Running for Reelection

Sources: Morningstar Direct, CAPTRUST Research

AI-Driven Productivity Boom

Rapid and accelerating advancements in the AI field offer the potential for enormous productivity gains across industries. Productivity is an essential driver of economic growth and prosperity, and AI offers the potential to turn nearly every company into a technology company by automating and expediting tasks, anticipating problems, and making workers more productive.

The growth of an economy can be evaluated by assessing the total number of workers and the amount of economic output per worker. While workforce growth has decelerated amid slower population growth, per-worker productivity could increase meaningfully as AI automates a greater number of tasks and speeds up innovation and processing times. Some economists estimate that AI will increase productivity by 0.5% annually over the next decade, equating to an additional $1 trillion in GDP.[2]

The Course Ahead

While expectations for a dovish Fed pivot fueled late 2023 returns, the first quarter of 2024 delivered strong results despite a pullback of those hopes. At the beginning of the year, investors were predicting as many as six rate cuts during 2024, but by the end of March, that number had dropped to three, in line with the Fed’s own projections.

Recent data reiterates that the final leg of the inflation course may take longer than expected to complete, with more volatility. The Consumer Price Index rose 3.5 percent in March from a year earlier, well ahead of the Fed’s 2 percent target, as both goods and services showed continued price pressures. The Fed is reluctant to cut interest rates too soon for fear of an inflation resurgence, and the strength of economic data provides more room for them to wait.

We remain optimistic that the economy will continue to show resilience amid a higher rate environment. Solid economic activity, including a robust labor market and continued consumer and business spending, has diminished recessionary fears. However, we are also aware that equity prices and investor sentiment reflect this optimism as well, posing risks of a pullback if economic activity begins to falter or expected earnings growth fails to materialize. There are also continuing concerns about potential vulnerabilities within the commercial real estate market and the threat of geopolitical flare-ups that could pose risks to supply chains, trade agreements, and energy prices.

Market participants must now brace themselves for a longer uphill stretch than hoped. For runners, pacing is critical to a strong finish. It’s smart to leave some gas in the tank for the last mile. For the economy, the prospect of higher-for-longer interest rates means the distance to the finish line has likely grown. As always, investors would be wise to evaluate how the strong market results of the past six months have affected their portfolios and financial plans to ensure they are well diversified for the uncertain course ahead.

[1] Asset class returns are represented by the following indexes: Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index (U.S. bonds), S&P 500 Index (U.S. large-cap stocks), Russell 2000® (U.S. small-cap stocks), MSCI EAFE Index (international developed market stocks), MSCI Emerging Market Index (international emerging market stocks), Dow Jones U.S. Real Estate Index (real estate), and Bloomberg Commodity Index (commodities).

[2] “New Work, New World,” Cognizant and Oxford Economics, 2024

Today’s evolution is not only a response to the financial pressures of shrinking margins but also a tactical shift toward offering a more comprehensive suite of products. It’s a shift that could make recordkeepers feel less like third-party vendors and more like strategic, mission-aligned partners.

These changes signal a new era for retirement plan sponsors and participants, one where the choice of a recordkeeper goes beyond basic recordkeeping to include a broad spectrum of financial wellness, technology, and personalized advice solutions. It also necessitates a change in the advisor’s role, with advisors now acting as guides or researchers to help plan sponsors understand and make decisions about each recordkeeper’s unique products, services, revenue streams, and outsourcing arrangements.

Navigating Continued Consolidation

In recent years, the retirement plan industry has witnessed a significant trend toward recordkeeper consolidation. This movement has been driven by a confluence of factors, including the pursuit of greater efficiency, the need to invest in and leverage advanced technology, and the desire to expand service offerings. As profit margins tighten and regulatory complexities increase, smaller recordkeepers find it challenging to compete, leading to mergers and acquisitions by larger entities.

It’s a drastic shift, but not a new one. “The recordkeeping landscape has shrunk dramatically from about 400 providers 15 years ago to only about 50 today,” says Mike Webb, CAPTRUST senior manager of plan consulting. “Consolidation is reshaping the whole industry of retirement plan services.”

For retirement plan sponsors, recordkeeper consolidation could lead to a more streamlined selection process as fewer, more capable providers dominate the market. However, the trend also raises concerns about reduced competition, the potential for higher costs over time, and the need for a sponsor to conduct due diligence to ensure their chosen recordkeeper aligns with their plan’s unique needs, goals, and values.

“Moreover, consolidation impacts the level of personalized service that sponsors and participants have come to expect,” says Webb. “As companies merge, there is a risk of service disruption or a decline in service quality during the transition period. Plan sponsors must be vigilant in managing these transitions to make sure their participants’ needs continue to be met without interruption.”

The average transition can take between six and 18 months, Webb says. Throughout that time, there are multiple fiduciary considerations to be aware of. “For plans where the current recordkeeper is the acquiree, sponsors should exercise the same degree of fiduciary due diligence in determining whether to remain with the new recordkeeper as they took to select the existing recordkeeper,” he says. “For plans where the current recordkeeper is the acquiror, sponsors should verify that the acquisition will not impact the recordkeeper’s ability to provide best-in-class service.”

The implications of consolidation also extend beyond the immediate operational aspects. Specifically, consolidation signals a shift in recordkeeper ethos, one where “recordkeeping itself is considered a fundamental expectation,” says Audrey Wheat, CAPTRUST manager of vendor analysis, while innovation, scale, and integration have become key competitive advantages. For plan sponsors, deciding how to move forward requires a keen understanding of their plan’s needs, their participants’ desires, and their recordkeeper’s strategic direction.

Strategic Partnerships and Outsourcing

“More than ever before, recordkeepers have to achieve economies of scale in order to sustain their margins,” says Wheat. “Downward pressure on fees has spurred a relentless pursuit of scale through consolidation and strategic partnerships. Essentially, recordkeepers are redefining their value propositions from traditional recordkeeping to a more holistic suite of services.”

For plan sponsors, this redefinition presents opportunities and challenges. The wider scope of products and services now available from recordkeepers can significantly enhance plan value and participant engagement. However, the variability in how outsourcing arrangements are implemented requires plan sponsors to thoroughly vet and understand the range of recordkeeper services available and their potential impact on service delivery and participant experience.

“On the recordkeeping side, there are typically three options: build, buy, or partner,” says Wheat. “For every new product or service, recordkeepers are asking themselves: Do we want to build this in house, acquire a company that’s already doing it well, or outsource the offering and provide it through a third-party partnership?”

While some recordkeepers now outsource nearly all their operations, others opt to outsource specific business functions, leaning into their strengths while tapping partners to help in areas where they aren’t as strong. “This varied approach to partnering or outsourcing—especially in areas like back-office processing or call center operations—allows recordkeepers to streamline their operations, focus on their core competencies, and leverage external expertise for non-core functions,” says Wheat. Outsourcing is one way for recordkeepers to refine their offerings and create internal efficiencies.

But these new services also introduce new risks for the plan sponsor, including fiduciary and cybersecurity concerns, which necessitate an additional layer of scrutiny and due diligence. How is the recordkeeper using plan data? Are they sharing personally identifiable information (PII) with their technology partners? And do those partners have the same level of data security as the recordkeeper? Plan sponsors are increasingly relying on advisors to help understand the answers to these questions.

Service Diversification

In the race for a competitive edge, recordkeepers are also diversifying their revenue streams by offering a suite of products and services that go beyond traditional recordkeeping. “Every recordkeeper has a side job,” says Wheat. “Differentiation increasingly hinges on supplementary offerings related to financial wellness, technology, or communication tools. Managed accounts, participant advice, health savings accounts (HSAs), and student debt management solutions are other common offerings.” These elements now serve as pivotal decision-making factors for plan sponsors.

Financial wellness programs have become a cornerstone of this differentiation strategy. By integrating financial wellness programs, recordkeepers not only provide a valuable service that extends beyond the basics of retirement planning but also offer a suite of solutions addressing the broader financial challenges that participants face. According to PwC’s 2023 “Employee Financial Wellness Survey,” when included as part of an employee’s benefit package, financial wellness programs may increase employee satisfaction, productivity, engagement, and retention.

“Financial wellness programs encompass a range of services, from personalized advice provided by financial advisors to account aggregation technology to manage net worth to educational content on budgeting, retirement readiness, and managing student loan debt,” says Chris Whitlow, CAPTRUST senior director of advice and wellness. “These tools can be critical to employees to help build their financial confidence and well-being.”

Technology and communication tools are also important. The deployment of user-friendly platforms that facilitate easy access to account information, educational resources, and personalized advice directly influences participant engagement and satisfaction. Recordkeepers that lead in technology innovation are offering participants features they value, such as mobile apps, artificial intelligence (AI)-driven financial planning tools, and interactive educational content.

“These advancements don’t just democratize access to financial information,” says Whitlow. “They also empower participants of all ages and incomes with the knowledge and tools they need to make informed financial decisions.”

The rise of these value-added services underscores a change in the recordkeeping business model. With recordkeeping fees compressed to near break-even points due to competitive pressures, recordkeepers are increasingly relying on their side jobs—that is, additional products and services—to sustain profitability.

“Plan sponsors know that recordkeeping fees have been compressed, and they see that the recordkeepers are offering a wider range of services,” says Wheat. “Naturally, they also want to understand how their vendor partners are making money.” That’s where an advisor can be especially helpful.

Advisors as Guides

As recordkeeper services have expanded, so too has the role of the financial advisor. “Advisors are rarely ever just managing investments now,” says Jennifer Doss, CAPTRUST senior director and defined contribution practice leader. Instead, they’re often helping plan sponsors understand how recordkeepers generate revenue and the implications for their retirement plans. “They navigate the nuances of each provider’s strengths, aligning them with the plan sponsor’s mission and the specific needs and desires of their participants.”

“The advisor’s job is to know the client,” says Doss. “Then they can use their expertise and client-specific knowledge to recommend the best solutions for that particular sponsor and their participants while also ensuring the recordkeeper’s fees are reasonable for the services offered.”

When navigating the choice between multiple recordkeepers, the best place to start is by naming what the plan sponsor values most, whether that means cutting-edge technology, extensive financial wellness programs, or a focus on participant education and advice. In making these decisions, the plan sponsor’s mission becomes a guiding light. It encapsulates the employer’s vision for employee welfare and drives the selection of benefits packages that align with both organizational goals and participant aspirations.

As recordkeepers evolve—embracing new roles and offering innovative solutions—the role of plan sponsor becomes ever more complex, yet ripe with opportunities. Navigating its nuances requires a discerning eye, one that can identify the true value behind enhanced technology platforms, comprehensive service offerings, and the promise of a better retirement planning experience for participants. With the guidance of a financial advisor and a clear understanding of their organizational goals and participant needs, plan sponsors are well positioned to make informed choices that align with their missions and values.

In the future, it seems the ecosystem of relationships between plan sponsors, recordkeepers, and advisors will continue to play a pivotal role in shaping a retirement planning environment that is both robust and responsive to the changing needs of the modern workforce.

The 2020 census revealed some surprising facts about the American population, including the second lowest growth rate in U.S. history and an aging populace. It also confirmed what many people already suspected: America is now more diverse than ever, especially when it comes to race and ethnicity.

For nonprofit leaders, this demographic data is evidence of the need to engage with donors across multiple cultures, generations, and backgrounds to be sure their organizations reflect the diverse communities they are trying to serve. Now and in the future, successful nonprofits need a diverse group of committed supporters to sustain themselves and thrive. Plus, there are other benefits to engaging a wider donor base, including increased funding, improved brand recognition, and access to new perspectives and ideas. By connecting with a broad and varied donor population, nonprofit leaders can also foster a more inclusive philanthropic community at large.

However, it should come as no surprise that simply asking new donors for money does not create a diverse donor population. Authentic donor engagement requires an intentional, strategic, and long-term approach.

Develop a Strategy

“Reaching new donor groups starts by understanding why the organization wants to make changes in the first place,” says CAPTRUST Financial Advisor Kevin Yoshida. For some nonprofits, the answer lies in a mismatch between their existing donor base and their community demographics. White donors and older generations are often overrepresented compared to their national—and sometimes local—population percentages. The risk here is that population incongruities may create an emotional disconnect between the organization and the community it serves.

Other nonprofits may need diverse donors in order to meet urgent fundraising needs. “When things are going well, it’s easy to become stagnant about your donor population,” says CAPTRUST Financial Advisor Paul Schreder. But as the saying goes, the best time to fix a roof is when it’s sunny.

To get started, consider performing a benchmark analysis of current donor demographics. Look for strengths and gaps. Which groups does the organization excel at attracting, and which groups are underrepresented compared to local population statistics? Consider not just race and ethnicity but also different genders, ages or generations, socioeconomic groups, and more.

Next, review the internal diversity represented by the organization’s board and staff. Then consider how to align internal and external demographics. For instance, Yoshida says, “If the community served is mostly women, but the nonprofit’s donor base plus staff and board members are mostly men, it may be smart to consider targeted campaigns to reach more women.”

Once the nonprofit has a clear picture of where it is starting from, leaders can begin to develop a specific and achievable vision of their ideal donor base and compose a diverse donor engagement strategy to get there.

Diversify the Organization

For organizations that discover a mismatch between internal demographics and their communities, one next step is to focus on recruiting a more diverse staff and board. “Diverse organizations may be better equipped to understand and engage with donors from various backgrounds,” says Schreder. “Plus, diverse leaders can use their personal connections to help the nonprofit create authentic connections.”

Yoshida points to one client who has been particularly successful with this approach. “The organization recently appointed a new board chair who is Hispanic,” he says. “By using her personal connections, the chair is helping improve the organization’s access to events and spaces where Hispanic communities gather.”

Another example: Imagine a nonprofit with a board of directors composed entirely of people over age 50 and an average employee age of 45 years old. By adding younger members to its board and younger employees to its staff, this nonprofit stands a greater chance of attracting younger donors as well. When people see themselves reflected in an organization, they are more likely to feel connected and to give.

However, it is important to acknowledge that diversifying an organization will take time. As Schreder says, “Nonprofits often have a hard time finding diverse staff—especially fundraising staff.” The pool of candidates is limited, so hiring can be highly competitive. But, he says, “long-term investment in people is almost always worth the effort.”

“If the organization is intent on building a diverse team, it can demonstrate that commitment by mentoring and training people who already have a passion for the work, although they may not yet have the necessary level of expertise or experience yet,” Schreder says. This applies to board recruitment too. It is beneficial to have a structured board training and onboarding program so that new members who don’t have prior board experience know they can get up to speed.

For more information on how to diversify your endowment or foundation’s board of directors, watch this short video: Building a Diverse Board Pipeline.

Grow Real Relationships

The next step is to build authentic relationship with the various communities the nonprofit has identified in its diverse donor engagement strategy. “Through these relationships, nonprofits can learn about the unique values, habits, and priorities of different demographic groups, then adapt tactics accordingly,” says Schreder.

Although it’s important to stay attuned to recent data about diverse groups, be careful not to rely too heavily on third-party research and reports, which can create a sense of insincerity in messaging. Remember that even the best surveys are designed to extract generic data from unique individuals, so it’s easy to draw false generalizations from oversimplified survey results.

For example, although researchers often try to decipher philanthropic trends by racial group, the Blackbaud “Diversity in Giving” study shows that “income and religious engagement are far more significant predictors of giving behavior than race or ethnicity.”

It is the combination of research and relationships that creates cultural competency.

But how can nonprofits with limited internal diversity cultivate these authentic relationships? Some ideas include focus groups, volunteer days, and hiring diverse content creators or content reviewers to help with donor engagement campaigns. Or consider partnering with local nonprofits that have diverse leaders and find ways each organization can support the other. Two other ideas are to create an advisory board comprised of diverse individuals who receive the organization’s services or ask representatives from the community to serve on your board of directors.

The “Everyday Donors of Colors” report produced by Indiana University’s Lilly Family School of Philanthropy gives four additional recommendations:

- support philanthropic efforts led by donors of color;

- provide leadership opportunities for donors of color;

- support wealth creation in communities of color; and

- provide support for additional research into diverse donor habits.

The report emphasizes that supporting wealth creation is especially important because “the capacity for ‘big gift’ philanthropy within some communities of color is constrained by wealth inequality.”

Although these recommendations focus specifically on race- and ethnicity-related diversification, they also apply to other demographic groups. For instance, if the organization wants to reach more baby-boomer donors, consider replacing the phrase “donors of color” in each of these bullet points with “donors from the baby-boomer generation.”

As nonprofit leaders have likely experienced throughout their careers, authentic relationships are the foundation of successful and sustainable donor engagement. By building trust and demonstrating genuine interest in diverse communities, organizations can create lasting connections that lead to long-term support.

Create Custom Campaigns

Once the organization has developed a diverse donor strategy and increased its cultural competency, it’s time to create personalized campaigns that reach new audiences in new places. One-size-fits-all fundraising campaigns will not resonate with all donors. Instead, nonprofits should consider creating tailored campaigns that speak to the unique interests and values of specific donor communities.

This starts by diversifying the organization’s brand imagery and learning best practices for inclusive language. It’s also a good idea to examine the organization’s current programming calendar to be sure it aligns with diverse holidays. Vary the types of events offered and when they will occur. Tie each piece of programming back to the organization’s donor research and engagement strategy, and make sure to involve people from the targeted community in the event-planning process. For instance, if the organization is pursuing more LGBTQ+ donors, celebrating Pride Month could be a good idea, but only if the celebration authentically benefits the LGBTQ+ community and involves LGBTQ+ community members as organizers and leaders.

Another way to tap new and diverse sources of support is to expand the search for donors beyond traditional advertising channels. By attending local events and leveraging social media platforms, organizations can connect with donors who may not have been reached through print or radio.

As an example, Schreder says he has seen increased interest in reaching younger donors from the Millennial and Gen Z generations. “These donors rarely respond to physical mail and are often more interested in donating time than money, at least at first,” he says. “But by creating connections with them now, nonprofits are building lifelong relationships for the future.”

Read more about connecting with younger donors in this article: “The Charitable Millennial.”

When deciding which platforms to leverage, remember to meet people where they are. Explore multiple social media apps, try both in-person and virtual events, and don’t be afraid to leverage tried-and-true advertising tools, like word-of-mouth marketing and door-to-door canvassing. Also consider using multiple fundraising software options. Complement organization-wide donor platforms like those offered by Blackbaud or Salesforce with other direct payment options like Venmo or GoFundMe.

By recruiting diverse board members and staff, building authentic relationships, and creating custom campaigns, nonprofits can build lifelong connections with diverse donors across multiple demographic groups. But this won’t happen by making small adjustments to existing engagement tactics. Instead, it means embracing a comprehensive strategy that prioritizes genuine connections and long-term support for diverse communities.

Each year, CAPTRUST releases its “Endowment and Foundation Survey” in an effort to identify nonprofit investment trends and concerns. The goal of this survey is to find out what nonprofits are doing and why, then share these findings to arm decision-makers with clear and actionable information that can help them make a positive impact. Responses in each section provide sector insights that can help inform growth, strategy, and internal practices.

In 2023, a shorter survey and a narrower scope of questions allowed for more responsive perspective sharing within the nonprofit community. Questions were focused on investments and asset allocation, and results showed two key takeaways: increasing interest in alternative investments and the continued rise of OCIOs. Both these findings reiterate multi-year trends.

Optimism Abounds

Survey results indicate that nonprofit investors are feeling decidedly more optimistic about this year’s investment landscape than they were at the end of 2022. Across the board, fewer nonprofits reported feeling concerned about future return expectations, market volatility, or inflation.

Buoyed by that optimization, endowments and foundations are now interested in increasing allocations to all investment types and reducing cash reserves.

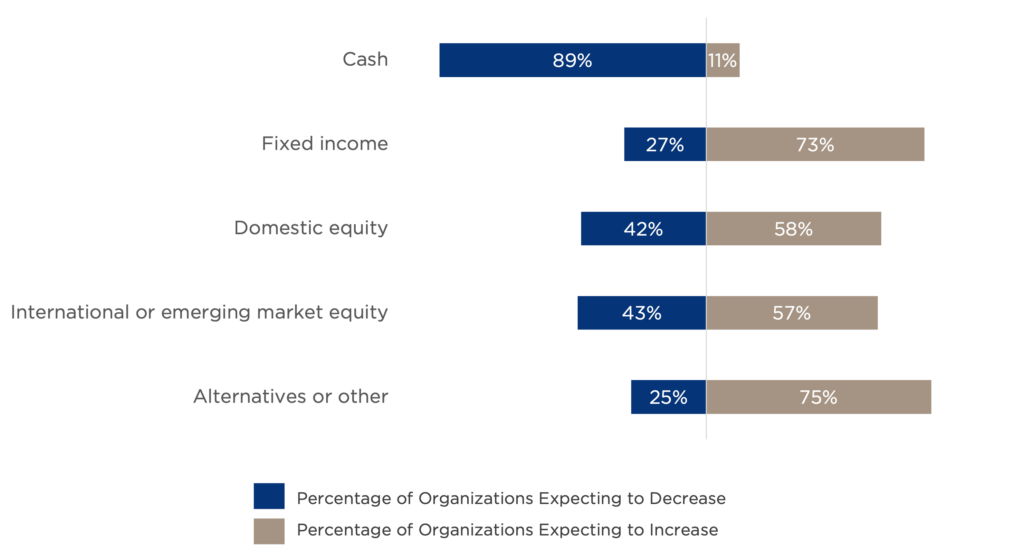

As shown in Figure One, 75 percent of organizations that are planning to shift their asset allocations said they anticipate increasing their allocation to alternative investments. This marks the fifth consecutive year that organizations planning for reallocation named alternative investments as their largest predicted area of change.

Figure One: Expected Changes to Asset Allocation

Source: CAPTRUST Research

Why Alternatives?

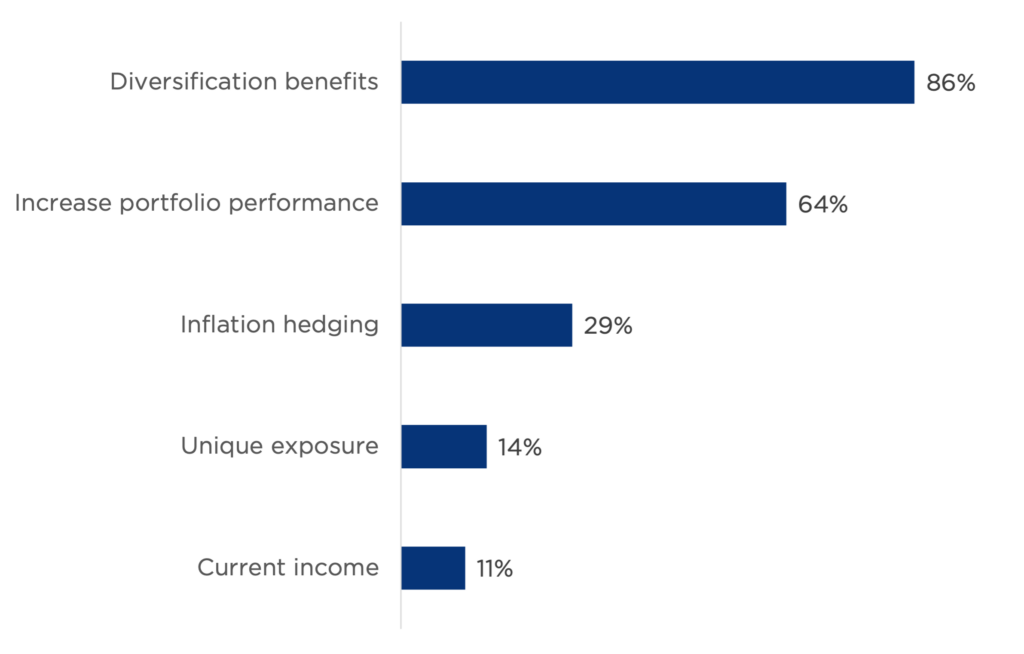

Alternative investment strategies vary greatly and can be used to meet a variety of organizational goals. In CAPTRUST’s 2023 survey, endowments and foundations that are turning to alternatives reported two common objectives: diversification (86 percent) and increased portfolio returns (64 percent), as shown in Figure Two.

Figure Two: Alternative Investment Objectives

Source: CAPTRUST Research

Diversification occurs primarily via exposure to different asset classes. In this case, it seems nonprofits want asset classes in addition to cash, stocks, and bonds. Furthermore, “since private markets are not correlated to traditional public market investments, they may offer a diversification strategy that potentially reduces portfolio risk,” says Pat Burkett, a manager on CAPTRUST’s investment research team.

Two additional potential benefits: Alternative investments may offer higher expected returns than traditional investments, and private market valuation practices may help mitigate market volatility.

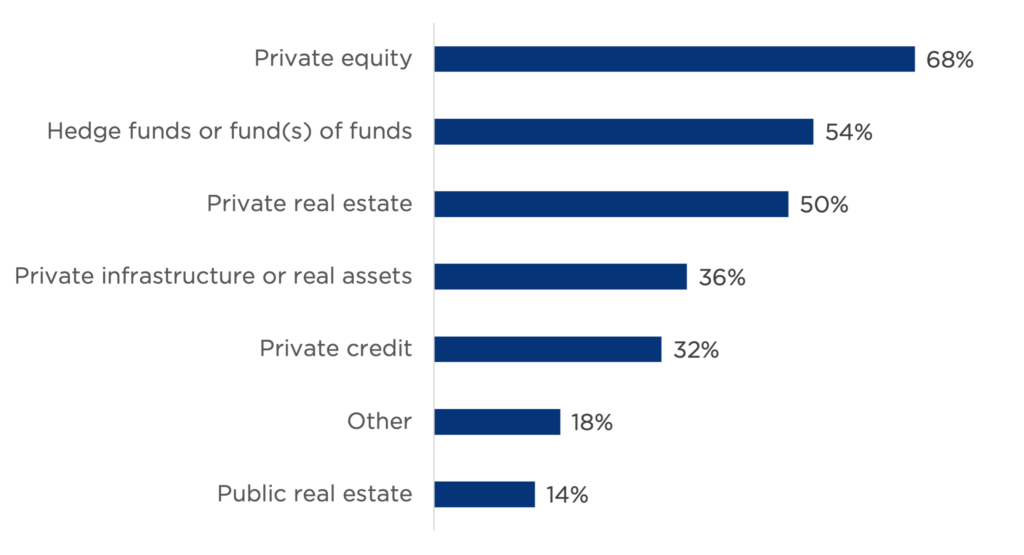

With these benefits in mind, it is not surprising that most nonprofits investing in alternatives are choosing to invest in private equity (68 percent) and other private markets strategies, such as real estate (50 percent), infrastructure (36 percent), and credit (32 percent), as shown in Figure Three.

Figure Three: Alternative Investment Strategies

Source: CAPTRUST Research

“While each strategy differs, all these types of private markets investments can provide access to unique opportunities but will also have unique risks,” says Will Volkmann, an investment research specialist at CAPTRUST.

For instance, many of these investments, such as private equity and private real estate, can be illiquid and challenging to sell quickly. “Investors in private markets may be rewarded with higher expected returns in exchange for committing to a longer time horizon,” says Volkmann. “But they’ll need to be sure that these long-term, illiquid investments are balanced by other, more traditional assets in case they need money in a pinch.”

Lack of regulation can also be a risk, as these investments may be subject to less regulatory oversight than stocks or bonds. Also, alternative assets can be subject to significant price fluctuations and higher fees compared to traditional assets. These risks are inevitable but can be mitigated.

Endowments and foundations considering alternative investments should make sure to do their due diligence or hire a professional with alternative markets expertise to vet the opportunity set.

Complexity and the Rise of OCIOs

Considering the time, effort, and expertise required to decipher alternative market opportunities, it is likely that this trend toward alternative investments is intertwined with another key finding from our “2023 Endowment and Foundation Survey”: the continued rise of OCIOs.

An OCIO is a professional advisor or advisory firm hired by a nonprofit to manage its investment portfolio and make strategic investment decisions on the organization’s behalf. Typically, an OCIO provides day-to-day management of the organization’s investment program, allowing nonprofit leaders to focus on their mission.

“The OCIO is directly accountable for portfolio performance and has investment discretion,” says Volkmann. That’s why the OCIO relationship is also sometimes called discretionary portfolio management or simply discretion.

This short video explains more: “OCIO for Nonprofits.”

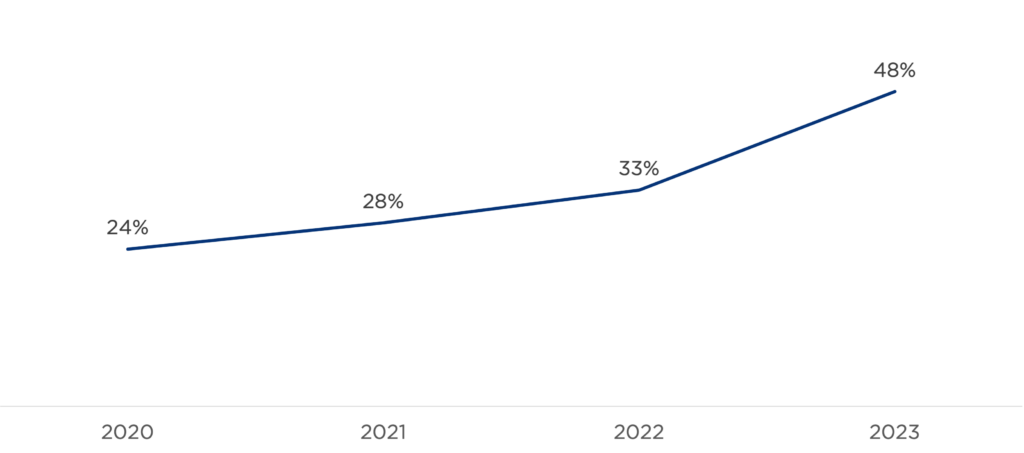

As shown in Figure Four, by the end of 2023, nearly half (48 percent) of endowments and foundations reported utilizing an OCIO—a percentage that has doubled in only four years.

Figure Four: Percentage of Organizations Utilizing an OCIO

Source: CAPTRUST Research

Many nonprofit board members believe delegating the investment manager search process to outside professionals will yield the best outcomes. However, Burkett says, “Perhaps the biggest benefit of hiring an OCIO is that it frees up time for internal staff to concentrate on other priorities.”

Nonprofit organizations often have no full-time staff members dedicated to investments. With an OCIO at hand, they have a full-time investment professional focused on their organization’s unique needs and objectives.

“Another benefit of the OCIO relationship—especially as it concerns alternative investments—is having someone else available to handle capital calls and distributions, and to fill out subscription documents, which can sometimes be time-consuming and cumbersome,” says Burkett.

However, engaging in OCIO may not be the right move for every organization. Those with well-resourced internal investment teams might not need one, and institutions that prefer direct control over investment decisions could find the discretionary relationship less appealing.

Looking Forward

Ultimately, these findings highlight the dynamic nature of the nonprofit investment landscape, where shifts in asset allocation and investment management often reveal evolving priorities and opportunities. By staying attuned to these trends, nonprofit leaders can proactively identify emerging challenges and take advantage of new avenues for growth and impact.

Whether it’s seizing opportunities for diversification through alternative investments or optimizing investment management processes through OCIO partnerships, a keen awareness of sector dynamics can empower nonprofit organizations to navigate uncertainty with resilience and foresight.

But paying attention to sector trends isn’t just about staying competitive. It’s about fulfilling the fiduciary duty to steward resources effectively to achieve the organization’s mission. In a rapidly changing environment, the ability to anticipate and adapt to shifts in investment strategies and practices can make all the difference in driving sustainable outcomes and maximizing social impact.

Written by James Stenstrom and Ben Smiley

What Is It?

The Corporate Transparency Act (CTA) is a new federal law that became effective on January 1, 2024.

It was enacted as part of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2021, with a goal of reducing money laundering through shell companies.

The CTA mandates that millions of entities report their beneficial ownership information (BOI) to the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), which is part of the U.S. Treasury department.

Although FinCEN and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) are both subsets of the U.S. Treasury, BOI reports will not be filed with the IRS, and the CTA is not part of the tax code. It is part of the Bank Secrecy Act, a set of federal laws that require recordkeeping and report-filing on certain types of financial transactions.

Who Will Be Affected?

The new law affects almost all limited liability companies, C corporations, S corporations, limited partnerships, and other closely held entities—both American and foreign-owned—that are registered to do business in the U.S.

The CTA refers to these organizations as reporting entities, meaning that they have an obligation to report information. Owners, principals, and other control persons involved in these organizations will have to provide information to the reporting entities.

Generally, if you were required to file articles of incorporation or similar documents with the Secretary of State in order to form, you will have a filing requirement under the CTA. Trusts, depending on state law, generally do not have to file such documents, and, therefore, will not have to file BOI reports. However, if a trust is created in a U.S. jurisdiction that requires such filing with the state, then it may be considered a reporting company.

There are 23 types of entities that are exempt from the reporting requirements. Some exempt entities include large companies, public companies, other regulated companies, tax-exempt entities, and inactive entities. Chapter 1 of FinCEN’s “Small Entity Compliance Guide” can help you determine whether your entity is required to file a BOI report.

Under the CTA, a beneficial owner is defined as any individual who directly or indirectly exercises substantial control over a reporting entity, regardless of their title or seniority. These individuals may or may not be actual owners of the company. However, any person who owns or controls at least 25 percent of the reporting company’s ownership interests is automatically considered a beneficial owner.

Organizations that have trusts as beneficial owners may need specialized help navigating the complexity of these requirements.

When Does This Start?

Entities formed before January 1, 2024, will have until January 1, 2025, to file their initial reports. Those formed during the 2024 calendar year have 90 days to file, and beginning in 2025, newly formed reporting entities will have 30 days to file their initial reports.

What Information Must Be Reported?

Beneficial ownership information refers to identifying information about the individuals who directly or indirectly own or control a company. This includes each individual’s name, address, email address, phone number, and more.

What If I Need to File Changes?

If there is any change to the required information about your company or its beneficial owners, your company must file an updated report within 30 days. This includes information related to address changes, ownership changes, or a change in senior officers.

Are There Penalties for Not Filing?

According to the CTA, a person who willfully violates BOI reporting requirements may be subject to civil penalties of up to $500 for each day that the violation continues. That person may also be subject to criminal penalties of up to two years of imprisonment and a fine of up to $10,000.

Potential violations include willfully failing to file a BOI report, willfully filing false beneficial ownership information, or willfully failing to correct or update previously reported beneficial ownership information.

What Actions Do I Need to Take?

If you are required to report your company’s BOI, you will do so electronically through a secure filing system. This system is available on FinCEN’s BOI e-filing website: boiefiling.fincen.gov. This is also where you can access the necessary form for reporting.

Business owners of newly formed reporting entities should talk to their business attorneys to confirm that all BOI filing deadlines and requirements are being met. Since the new law is not connected to a tax filing, there will likely be no need to contact your tax professional unless you do not have a business attorney.

Those who may be considered beneficial owners of established entities may want to contact their legal counsel, tax preparer, or business entity.

For help determining the next steps forward, reach out to your CAPTRUST financial advisor, or click the Talk to an Expert button to find a financial advisor in your area.

Budesheim, 79, ended up in the emergency room and then a catheterization lab, where doctors found that one of her arteries was fully blocked. Afterward, Budesheim’s daughter bought her an Apple Watch to keep track of her heart health. The watch includes an ECG app and can measure blood oxygen saturation, heart rate, and more.

Of course, the ECG in her watch is not as sophisticated as the ones used in hospitals, but Budesheim says it’s still comforting to have in reach. “It won’t detect a heart attack,” she says. “But it will tell me if I go into atrial fibrillation. And if that happens, I know I need to get in touch with the hospital or the doctor very quickly.”

Since Budesheim lives alone, fall detection is another important feature of her Apple Watch. “My watch does a whole lot of things,” she says. “But I am worried more about my heart than anything else.”

This worry puts Budesheim in good company. According to data from Johns Hopkins University, a desire to track their heart health is one of the top two reasons why people use wearable health-tracking devices. (The other is exercise tracking.)

Budesheim tests herself for atrial fibrillation at least once a day, and sometimes more. “If I get stressed or something just doesn’t feel right to me, I’ll think, Let me just check my watch,” she says. “I get some reassurance that if something happens, the watch is going to give me a little heads-up.”

Fact Finding

As technology advances and prices decrease, health-tracking apps and wearable devices are becoming increasingly popular. In 2023, 40 percent of American adults reported using health-related apps as part of their daily routines, and 35 percent used at least one wearable device, such as a Fitbit, Apple Watch, WHOOP band, Oura Ring, or digital pedometer, according to Morning Consult.

David Stewart, 65, of Park City, Utah, says apps and wearables are only part of the larger health-tracking trend. As host of the SuperAge podcast and founder of ageist.com, a media site that aims to break stereotypes of aging, Stewart keeps his finger on the pulse of health-tracking trends for people aged 50 and older. But health is also one of his personal passions.

Stewart tracks his own health with multiple wearable devices plus quarterly blood work through InsideTracker and an array of yearly check-ins with various physicians. His annual exams include a bone density scan, hearing test, and “all the usual” recommended physical examinations for people his age, such as a colonoscopy, prostate cancer screening, dental visits, and eye exams. He says the greatest benefit of consistent tracking is that it helps identify potential issues before they become bigger problems.

For instance, Stewart says, his latest blood work revealed low iron and calcium levels, and various tests have made him realize he struggles to metabolize vitamin D. So he supplements with all three and hones the dosage of his supplements based on each quarter’s blood test.

“You can only improve what you can track,” Stewart says. “If you’re not tracking, you’re just guessing. It’s great to be intuitive. But feelings are not facts.”

Prioritizing Prevention

Stewart says he thinks health care today is oriented toward disease treatment, not prevention. This is a common criticism within the circles of experts and consumers who support health tracking. “Health tracking is about optimizing your health before you can ever get to a disease state,” he says.

Evan Melcher, a CAPTRUST financial advisor in Alpharetta, Georgia, says health-tracking data provides a starting point for planning. “We can’t shape the future if we don’t know where we’re starting from,” he says. “These tests and check-ins and devices, they’re not complete solutions. They are tools that can help guide you to make more informed decisions and, hopefully, create better health outcomes.”

Budesheim agrees. In fact, she says she knows the exact moment when she really started paying attention to her health data—long before her heart attack. “I was never a real health nut until my husband passed away.”

“It was very sudden,” she says. “We found out he was sick on a Friday, and Monday, he was gone. In my head since then, I’ve always had this voice saying, Nothing is going to sneak up on me. I’m going to be listening to my body. I’m going to be proactive with my health care. All the tests you have to get, the preventive stuff, I’m there. Sign me up.”

In addition to the data she gathers from her watch, Budesheim keeps a folder that contains years of results from cholesterol tests, mammograms, and more. She uses this information to make sure her new healthcare providers have a robust picture of her health history and trends. But health tracking isn’t only about long-term disease prevention. It might also help you create healthier daily habits.

More Good Habits

“What I’ve found over time is that I’m either spiraling up, or I’m spiraling down,” Melcher says. “It’s not one thing you do that keeps you healthy for life. It’s a lot of little things that add up, and they are all connected like dominos.”

Melcher says health tracking has shown him how his daily choices impact his health. “I had back surgery a few years ago,” he says. “When I was recovering, I couldn’t exercise or anything, so I put on some unwanted weight. Also, I was indulging in too much red wine at night, which was affecting my sleep. There were all these trends that were going in the wrong direction.”

When he was able to exercise again, Melcher says he started to feel better. “I was seeing improvements in almost all my metrics, except in sleep quality. So I quit drinking. My sleep score improved significantly, and my LDL-C cholesterol level also started to drop.”

Melcher began to view his wearable devices as accountability partners, encouraging him to keep up his good habits and avoid bad ones. Now, he uses an Oura Ring, an Apple Watch, a Qardio at-home blood pressure monitor, and a body composition scale. Plus he gets regular blood work through his cardiologist. Heart disease runs in his family, so he stays attuned to his heart health, like Budesheim.

Most of Melcher’s tools report directly to his phone, which he uses as the central location for all his health data.

“I try to keep moving in the right direction with baby steps that add up to a lot of good things because I want to be here for my wife and kids,” Melcher says.

By paying attention to his metrics, then tweaking his habits slightly but consistently, Melcher says he’s seen dramatic health improvements. His resting heart rate has dropped by 10 beats a minute on average over the past year. “That’s more than five million heartbeats a year that I’m saving,” he says. “My heart is thanking me over and over again.”

The New Doctor-Patient Partnership

Culturally, the relationship between healthcare professionals and consumers is shifting, perhaps in part because of health-tracking tools. Patients have access to more information than ever, and many are eager for a more collaborative relationship.

“There’s no longer just a physician behind a curtain interpreting your information and handing down advice,” Stewart says. Instead, consumers are becoming equal partners in the decision-making process.

But of course, consumers also have access to misinformation and poorly interpreted studies. In a survey conducted by Merck Manuals, 97 percent of primary care providers said patients have come to them with misinformation they found online.

For Stewart, learning more about how his body works is part of being an informed healthcare consumer. “Having health data allows a greater sense of partnership with the practitioner,” he says. “But we have to remember that those practitioners are infinitely more skilled than we are.” Mutual respect and humility are important to the doctor-patient partnership.

Budesheim says she feels empowered by what she’s learned but tries not to obsess over the details.

“If I see or I feel something that isn’t right, I check it out,” she says. “I’m not obsessive about it. I don’t diagnose myself. But understanding what might be happening gives me peace of mind.”

She has some friends who disagree. For these people, health tracking feels like opening Pandora’s box. They worry about what they might discover and whether they’ll be equipped to handle it. Tracking like Budesheim, Melcher, and Stewart do is not for everyone, and people can rely too heavily on their devices for predicting or managing health outcomes.

Also, when it comes to sleep specifically, there is some evidence that tracking can have a negative impact on outcomes. The Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine calls this orthosomnia: a fixation on achieving perfect sleep data that leads to anxiety and disrupted sleep.

For some, information can create fear. For others, it can lead to obsession. Those who most enjoy and benefit from health tracking seem to avoid both extremes.

“If we’re willing to be informed and not alarmed by information, we can make better lifestyle choices,” says Melcher. “We can hack the system a little bit. And when we do, we give ourselves a better opportunity to live longer, healthier lives that can impact more people.”

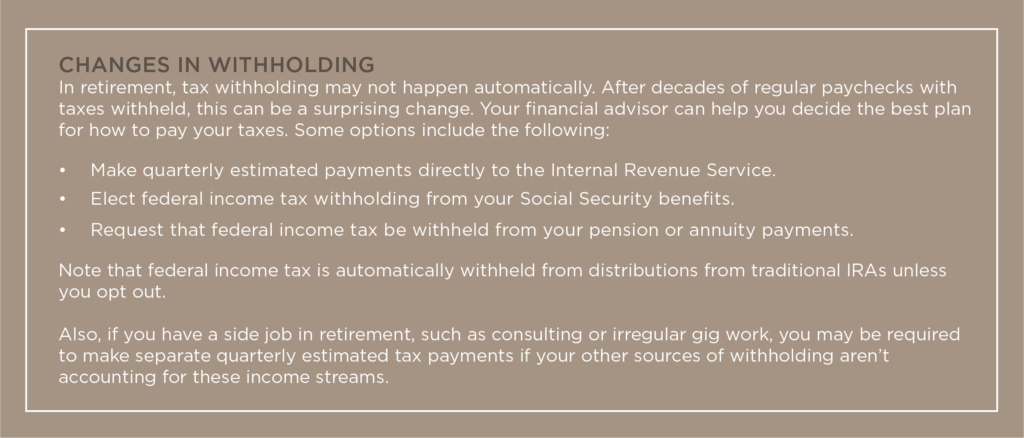

“The tax implications that accompany retirement decisions can significantly impact a person’s overall financial landscape,” says Jennifer Wertheim, director of tax planning at CAPTRUST. “That’s why tax planning is such an important part of financial planning overall. It’s a way to safeguard your hard-earned assets and stretch your savings.”

“Retirement tax planning relies on four pillars,” says Elisabeth Jacobson, a CAPTRUST financial advisor in Lone Tree, Colorado. “Know how your assets will be taxed. Develop a strategy for how you’ll withdraw money. Avoid things that are going to put you in a higher tax bracket. And review your tax situation whenever life changes.”

Jacobson says she has seen many cases where new clients could have benefited from earlier planning for retirement taxes. “There are so many people who are good at saving and investing but aren’t aware of how their accumulated assets will be taxed when they are sold or withdrawn,” she says.

For instance, Jacobson says she once met with a couple who had already started taking required minimum distributions (RMDs) from their retirement accounts. RMDs are minimum amounts that must be withdrawn annually from individual retirement accounts (IRAs) and qualified retirement plans, like 401(k) or 403(b) accounts. Your birth year determines when you must start taking RMDs. Generally, they are required once you reach your early 70s.

“These clients had done a great job saving money, but they’d put all their savings into a taxable IRA,” says Jacobson. “That meant every single dollar they had was going to be taxed. And their RMDs were huge, so every time they withdrew money, they were raising their marginal tax bracket—and their tax bill—even further.” Incorporating projected taxes into your financial plan can help avoid mistakes like this.

“It’s impossible to predict what tax rates will be in a decade or more,” says Philip D’Unger, a manager on CAPTRUST’s wealth planning team. “And regardless, these rates are likely to change throughout your retirement years, which may be a long time considering life expectancy today.”

According to the MIT AgeLab, the average American can expect to live roughly 8,000 days—more than 20 years—in retirement, assuming they retire at age 65. “The goal is to be financially resilient, whether you live to 75 or 105,” says D’Unger.

Balance What Is Taxable

“It’s important to know all your possible sources of retirement income and how each one will be taxed,” says Jacobson. To start, make a list of your assets. Label which ones are taxable and which ones aren’t. If you aren’t sure about a particular asset, talk to your financial advisor. “Then, you can develop a thoughtful strategy to make sure you have the funds you need while also minimizing tax consequences.”

Some assets, such as Roth accounts, will be tax-free. Others, like pensions, will be fully taxable. You may see a third set of assets labeled as tax-deferred. This includes traditional IRAs and 401(k) plans. You don’t pay taxes on dollars in these accounts until you withdraw them.

“Ideally, you will have some balance of taxable and nontaxable assets from which to draw your retirement income,” says D’Unger. If your assets are out of balance, or you aren’t sure, talk to your financial advisor about rebalancing.

“As financial advisors, we talk a lot about diversification of assets, but having diverse accounts is also important,” says Jacobson. “With a balance of taxable and nontaxable assets, you give yourself more options, more flexibility. Once we see the full picture of where a person’s assets are being held, we can make sure they have a portfolio that will help them cover their expenses while managing tax implications.”

“For instance, you may have built up substantial amounts of money in the taxable and tax-deferred buckets, but not enough in the tax-free bucket,” says D’Unger. “Rebalancing can help you minimize and prepare for future tax consequences. And it can help you spread your tax consequences across multiple years so that your tax bill is more predictable.”

Make a Withdrawal Plan

“Having a financial plan that includes estimated taxes in retirement can help you avoid unwanted surprises,” says D’Unger. It can also help estimate what your spending may look like as you age.

Jacobson says people tend to spend more money in the first few years of retirement than they spend later. “Those early years can be a sweet spot for tax planning,” she says. “You don’t need to have everything figured out before you retire. But it’s a good idea to sit down in those first few years and figure out the big pieces of your new financial plan.”

For instance, Jacobson says she helps clients understand when to start taking Social Security benefits, when to sign up for Medicare, and when they’ll be required to take RMDs. “RMDs are a big piece we manage around,” she says.

“Up to 85 percent of Social Security benefits may be taxed, and RMDs are taxed at the ordinary income tax rates,” says Wertheim. “Deferring your distributions as long as you can makes sense from a tax perspective, but how long you can defer will depend on your retirement income needs.”

Capital gains are another factor to consider. If you sell a capital asset, you’ll need to pay capital gains taxes on the profits. Capital assets include stocks, bonds, real estate, coin collections, jewelry, and digital assets like cryptocurrencies.

Long-term capital gains tax rates are set at 0, 15, or 20 percent and apply to any investment owned for more than one year. Short-term rates are determined by a taxpayer’s ordinary income tax bracket and apply to assets owned for less than a year. This means long-term rates will be lower than short-term ones.

“There are multiple tax strategies that can help you take advantage of lower capital gains tax rates,” says Wertheim. “But mostly, you want to make sure you are being strategic about when you sell your capital assets so that your profits from the sale don’t unintentionally bump you into a higher tax bracket for the year.”

Capital gains can also increase Medicare premiums. “If you have a higher income year—for instance, because you’re selling real estate or some other large asset—pay attention to your Medicare premiums,” she says. “The Medicare system may automatically assume this new, higher number is now your regular yearly income.”

Wertheim recommends people pay attention to state tax rules as well. “There may be nuances at the state level that also allow for specific tax planning,” she says. “In particular, it’s important to understand how retirement income is taxed in your state before finalizing your financial plan.”

For example, Jacobson says, “Retirees can deduct between $20,000 and $24,000 in retirement income from state taxes in Colorado, depending on their age.” This means income from Social Security and pension plans may be mostly or entirely state-tax-free for many Colorado residents.

Give Strategically

Once you start taking RMDs, you may find yourself in a higher tax bracket. One way to minimize the tax consequences of a higher income is through a qualified charitable distribution (QCD). A QCD is a tax-free donation directly from your IRA to a qualified charity. Although there’s no tax deduction for these donations, making a QCD can reduce your RMD in a given year without boosting your overall income.

“In 2024, anyone over 70 1/2 can contribute up to $105,000 directly from their IRA to a qualified charity,” says Jacobson. “This can help you meet your charitable goals and simultaneously meet your annual RMD. Plus, you don’t get taxed on it! It’s a triple win.”

“Giving to a 529 education fund is another way to satisfy a gifting goal, and you’ll typically get a state tax deduction,” says Jacobson. “We used to advise against this strategy because it sometimes affected financial aid eligibility for the recipient, but the rules have recently changed. Now, it makes more sense for more people.”

Another option to mitigate your tax bill is to use a donor-advised fund (DAF). This is a charitable investment account that lets you donate cash, securities, or other assets to qualified public charities.

“If you contribute to a donor-advised fund at about the time you retire, you can claim a federal income tax deduction for the year in which you make the donation,” says D’Unger. “Later in retirement, if you sell a capital asset, a DAF can also help you avoid the capital gains tax that would be due on the sale.”

“Taxes are inevitable,” says Jacobson. “But they can be managed. Having a retirement income plan that accounts for taxes can make your tax bill more predictable. It can give you confidence to spend what you’ve worked so hard to save.”

Written By Neil Downing

What is the actual value of a dollar? The obvious answer is 100 cents. However, this purely financial assessment fails to account for emotional attachment. There are, essentially, four different types of dollars investors encounter, and each has a different emotional value. Failing to understand the differences among the four has disrupted many well-designed investment plans.

Theoretical Dollars

The first type of dollar is one that investors often meet at the beginning of their investment journeys. These are purely theoretical dollars. They exist only in statistical models. Still, they’re important because they help establish expectations for long-term returns and short-term setbacks that could happen along the way.

Theoretical dollars are the foundation of all strong investment programs and financial plans. Using complex modeling tools and customized investor data, advisors can demonstrate a range of future outcomes that shift, depending on interim inputs. The future net worth they estimate, minus your net worth today, is composed entirely of theoretical dollars. At best, these dollars have no emotional value. At worst, they can be misleading—especially if we let ourselves get emotionally attached.

It’s difficult for the human brain to forecast feelings of loss. Visualizing joy is much easier. That’s why, although we often underestimate how we will feel after a surprise market dip, we can easily slip into daydreams about spending our theoretical dollars at age 70, when we’re on a beach somewhere with our loved ones.

Theoretical dollars are important, but keep in mind, they are not real.

Statement Dollars

As investors successfully navigate their journeys, theoretical dollars gradually become statement dollars. These are real dollars, built by discipline, sacrifices, and time. But they are invested, illiquid, and hopefully, growing. The effort required to accumulate these dollars creates a connection that gives them emotional value.

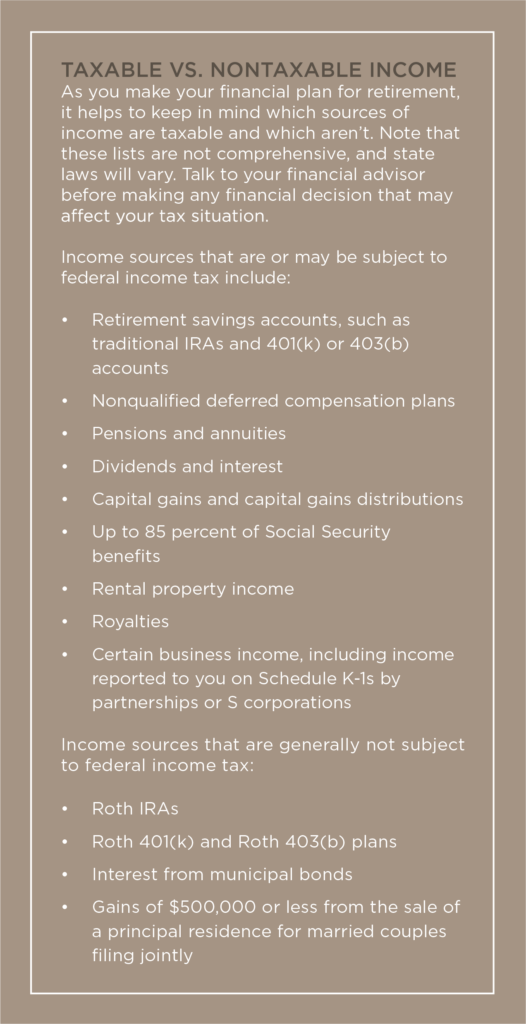

Statement dollars are like a scoreboard—one that can be checked every day. Their emotional characteristics are driven largely by two conflicting definitions of success: absolute success and relative success. Absolute success means setting a clear, immovable objective like a specific dollar amount or percentage growth. If portfolio returns exceed this objective, the investor can declare victory.

Relative success means evaluating portfolio performance compared to a similar portfolio or benchmark. For instance, many investment portfolios aim to outperform the S&P 500 Index. If the S&P 500 falls 2 percent, but the investor’s portfolio falls only 1 percent, this is considered a relative success. Because relative success has no absolute requirements, it can be measured in both up markets and down markets. However, it is important to remember the old Wall Street proverb that “you can’t eat relative performance.”

Both measures of success carry emotional risk because it’s human nature to want to outperform. A truly emotion-free portfolio—one that delivers absolute success in down markets and relative success in up markets—exists only in theory.

It doesn’t matter how much statistical modeling we do. Nothing can replicate, and no one can avoid, the emotional value of statement dollars. But each investor’s time horizon often determines how much emotional value they have. Thus, one piece of a financial advisor’s job is to keep investors focused on the long term. Like a fisherman pitching and rolling in a boat, watching the horizon can stabilize perspective.

The Spendable Dollar

Once a statement dollar is deemed spendable, its emotional value climbs dramatically. Statement dollars can rise and fall, but the spendable dollar (also known as cash) is king.

People feel real emotional pain when separated from their spendable dollars. That’s why the government withholds taxes before paychecks can be cashed. It’s why casinos use chips instead of real money. And it’s why companies encourage saving via payroll deductions. Once we feel a sense of permanent ownership over our spendable dollars, they’re much harder to let go of.

From an investment perspective, the emotional impact of a spendable dollar is often seen when an investment distributes income. Income is the least tax-efficient way to grow wealth, and taxable investors should nearly always choose unrealized gains instead.

Most investors view unrealized gains as statement dollars until they are sold or withdrawn. Then, they become spendable dollars and may feel more permanent.

While income-producing strategies can be an important part of a well-diversified portfolio, overexposure or a premature conversion of statement dollars into spendable dollars (like selling stocks) can significantly reduce the portfolio’s long-term value. Yet, the comfort of watching a spendable balance grow can tempt even the savviest investors.

The Spent Dollar

Generally, there is only one definition of a spent dollar. It is a spendable dollar we used to own, and now we don’t. This can be highly emotional. When dealing with spent dollars, investors often lose rational perspective.

Of course, not all spent dollars have the same value. We enjoy spending when it is voluntary and rewarding but usually not when we are forced to spend money on taxes, speeding tickets, or insurance premiums. These dollars often carry a sense of loss, and we commonly resist spending any dollar that has been hard-earned, diligently saved, or long-awaited. This resistance can lead investors to make imprudent investment decisions, but it typically makes an even bigger impact on planning.

Even if a strong foundation was established via theoretical dollars, the emotional roller coaster of statement dollars was successfully navigated, and the conversion to spendable dollars was perfectly planned, there is always a heightened sense of doubt when turning a spendable dollar into a spent dollar.

Why? Throughout the other three phases, time generally rewards you, healing wounds, providing flexibility, increasing options, and maximizing the power of compounding. But a spent dollar reverses the clock, turning time into an adversary by reducing future options. Nothing feels more limiting than a permanent decision, and spent dollars are spent, forever.

Navigating Emotional Values

Investing is emotional because saved money and long-invested assets often require sacrifice, patience, and persistence. These emotions can be clearly defined, and even predicted, but rarely avoided. To push back against the natural cognitive tendencies that lead to emotional decision-making, consider these four suggestions.

Be wary of using theoretical dollars to define risk tolerance. A risk profile that feels right with theoretical dollars will inevitably feel wrong when hard-earned statement dollars decline in value.

Attempt to prioritize which definition of success is most important to you, then manage statement dollars accordingly.

Try to resist the allure of spendable dollars from cash distributions. Even if they are reinvested into statement dollars, some portion will be spent on taxes. If they aren’t reinvested, you could miss out on future gains and still have to pay taxes.

Finally, when it is time to spend, spend. Enjoy the rewards of a successful investment journey.

The fear of running out of money is real and powerful. Consequently, many retirees fail to fully capture the value of their prudent historical decisions. A financial plan is a critical piece of the investment journey not only because it helps build wealth, but also because it can give you permission to enjoy what you’ve constructed. Remembering the differences among these four types of dollars can also be helpful, especially if it helps us mitigate our natural emotional connections.

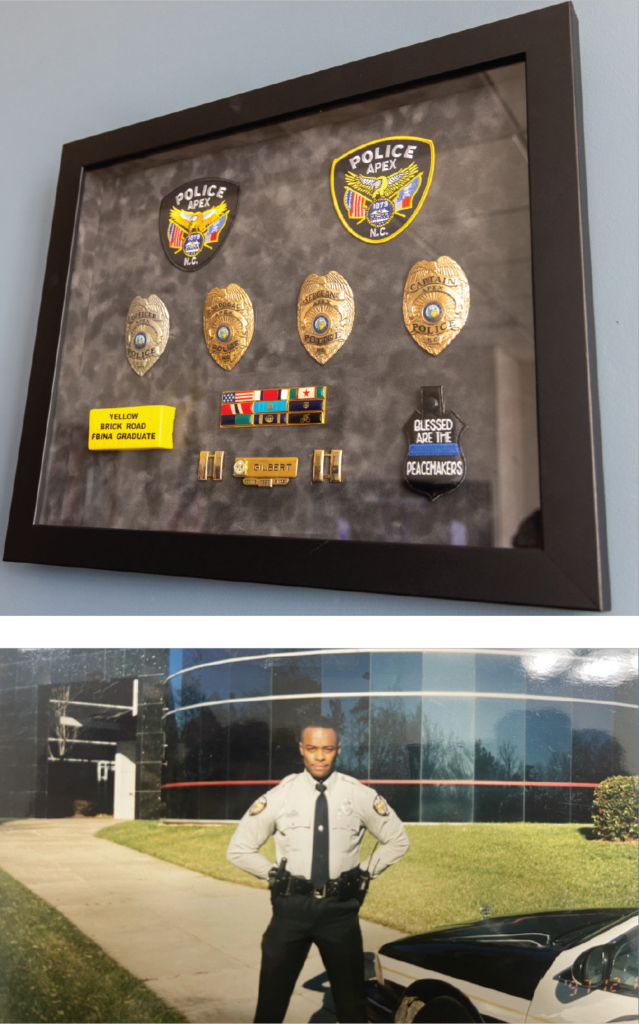

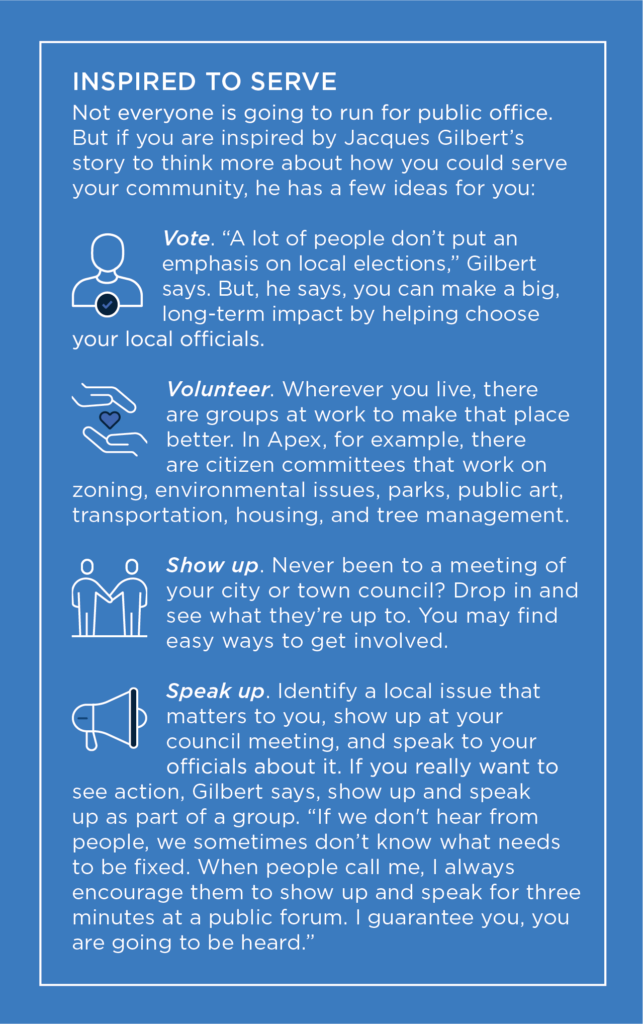

In 2019, Gilbert cleaned out his locker at the Apex, North Carolina, police department and officially retired from what he calls a highly unlikely 29-year career in law enforcement. Gilbert grew up in a culture where people distrusted and sometimes disliked police officers. Yet by all measures, he’d become a hugely successful one.

After a lifetime in the force, he put his uniform and badge away, turned off the lights, and walked out the door into charming, historic downtown Apex. “It’s been a great ride,” Gilbert wrote at the time. “On to my next assignment.”

This sign-off, he says, contained a hidden message. Gilbert was about to do something he once thought was even more unlikely than becoming a police officer. Seven months later, he was elected mayor.

Gilbert, now 54, grew up in Apex. His neighborhood, Justice Heights, was on the other side of what he says was a clear dividing line marked by State Highway 55. Most Black people lived on one side, he says, and people on the other side didn’t see the neighborhood or the people who lived there as part of their town.

Now, Apex is different—more diverse, more developed, and much larger. In 2023, the town’s total population was 77,000. In the 1970s, when Gilbert was a child, it hovered around 3,000.

Gilbert lived in public housing, where he witnessed repeated hardships in his community. He had friends and relatives who got in trouble with the police. Although he never had any personal run-ins with law enforcement, he got the message that police officers were not to be trusted. He certainly never dreamed of becoming one.

When Gilbert graduated from high school in 1987, he went to work as a water meter reader for the nearby town of Cary. “It was just a job,” Gilbert says, and he wanted something that felt meaningful.

“A friend of mine became a police officer,” Gilbert says. “At first, I thought, that’s not for me. In the community where I was raised, being a police officer, that’s not what we do. It’s not who we are. But my friend kept sharing all the great things he was doing, and it just really intrigued me.”

Gilbert let his curiosity lead the way, enrolling in criminal justice courses at a community college and working his way through the North Carolina Coastal Plains Police Academy. After graduation, he says, “Everything just started opening up.”