-

Solutions

- Solutions

-

Individuals & Families

- Individuals & Families

- Individual Investors

- Executives & Business Owners

- Families with Complex Needs

- Professional Athletes

-

Retirement Plan Sponsors

- Retirement Plan Sponsors

- Corporations

- Educational Institutions

- Healthcare Organizations

- Nonprofits

- Government Entities

- Endowment & Foundation Leaders

- See All Solutions

Comprehensive wealth planning and investment advice, tailored to your unique needs and goals.Investment advisory and co-fiduciary services that help you deliver more effective total retirement solutions.CAPTRUST provides investment, fiduciary, and risk management services for nonprofit organizations. -

About Us

- About Us

- Our People

- Our Story

- Learn About CAPTRUST

-

Locations

-

Resources

- Resources

- Articles

- Podcasts

- Videos

- Webinars

- See All Resources

“The tax implications that accompany retirement decisions can significantly impact a person’s overall financial landscape,” says Jennifer Wertheim, director of tax planning at CAPTRUST. “That’s why tax planning is such an important part of financial planning overall. It’s a way to safeguard your hard-earned assets and stretch your savings.”

“Retirement tax planning relies on four pillars,” says Elisabeth Jacobson, a CAPTRUST financial advisor in Lone Tree, Colorado. “Know how your assets will be taxed. Develop a strategy for how you’ll withdraw money. Avoid things that are going to put you in a higher tax bracket. And review your tax situation whenever life changes.”

Jacobson says she has seen many cases where new clients could have benefited from earlier planning for retirement taxes. “There are so many people who are good at saving and investing but aren’t aware of how their accumulated assets will be taxed when they are sold or withdrawn,” she says.

For instance, Jacobson says she once met with a couple who had already started taking required minimum distributions (RMDs) from their retirement accounts. RMDs are minimum amounts that must be withdrawn annually from individual retirement accounts (IRAs) and qualified retirement plans, like 401(k) or 403(b) accounts. Your birth year determines when you must start taking RMDs. Generally, they are required once you reach your early 70s.

“These clients had done a great job saving money, but they’d put all their savings into a taxable IRA,” says Jacobson. “That meant every single dollar they had was going to be taxed. And their RMDs were huge, so every time they withdrew money, they were raising their marginal tax bracket—and their tax bill—even further.” Incorporating projected taxes into your financial plan can help avoid mistakes like this.

“It’s impossible to predict what tax rates will be in a decade or more,” says Philip D’Unger, a manager on CAPTRUST’s wealth planning team. “And regardless, these rates are likely to change throughout your retirement years, which may be a long time considering life expectancy today.”

According to the MIT AgeLab, the average American can expect to live roughly 8,000 days—more than 20 years—in retirement, assuming they retire at age 65. “The goal is to be financially resilient, whether you live to 75 or 105,” says D’Unger.

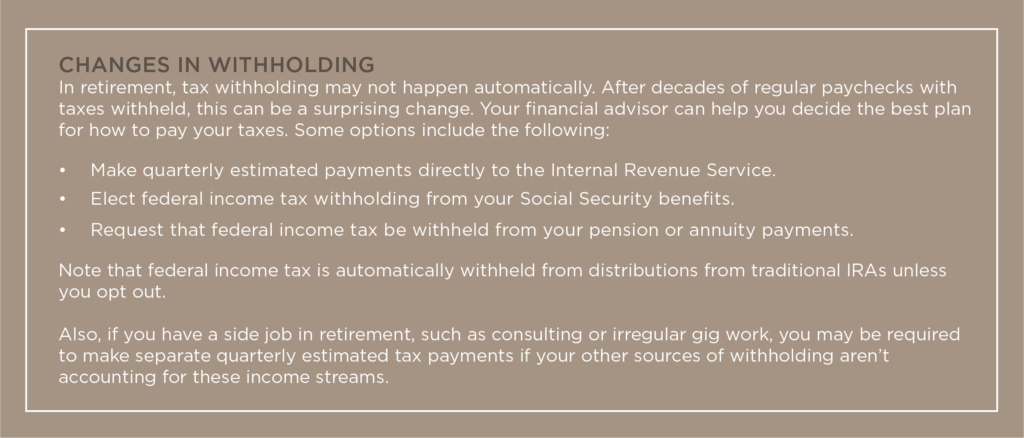

Balance What Is Taxable

“It’s important to know all your possible sources of retirement income and how each one will be taxed,” says Jacobson. To start, make a list of your assets. Label which ones are taxable and which ones aren’t. If you aren’t sure about a particular asset, talk to your financial advisor. “Then, you can develop a thoughtful strategy to make sure you have the funds you need while also minimizing tax consequences.”

Some assets, such as Roth accounts, will be tax-free. Others, like pensions, will be fully taxable. You may see a third set of assets labeled as tax-deferred. This includes traditional IRAs and 401(k) plans. You don’t pay taxes on dollars in these accounts until you withdraw them.

“Ideally, you will have some balance of taxable and nontaxable assets from which to draw your retirement income,” says D’Unger. If your assets are out of balance, or you aren’t sure, talk to your financial advisor about rebalancing.

“As financial advisors, we talk a lot about diversification of assets, but having diverse accounts is also important,” says Jacobson. “With a balance of taxable and nontaxable assets, you give yourself more options, more flexibility. Once we see the full picture of where a person’s assets are being held, we can make sure they have a portfolio that will help them cover their expenses while managing tax implications.”

“For instance, you may have built up substantial amounts of money in the taxable and tax-deferred buckets, but not enough in the tax-free bucket,” says D’Unger. “Rebalancing can help you minimize and prepare for future tax consequences. And it can help you spread your tax consequences across multiple years so that your tax bill is more predictable.”

Make a Withdrawal Plan

“Having a financial plan that includes estimated taxes in retirement can help you avoid unwanted surprises,” says D’Unger. It can also help estimate what your spending may look like as you age.

Jacobson says people tend to spend more money in the first few years of retirement than they spend later. “Those early years can be a sweet spot for tax planning,” she says. “You don’t need to have everything figured out before you retire. But it’s a good idea to sit down in those first few years and figure out the big pieces of your new financial plan.”

For instance, Jacobson says she helps clients understand when to start taking Social Security benefits, when to sign up for Medicare, and when they’ll be required to take RMDs. “RMDs are a big piece we manage around,” she says.

“Up to 85 percent of Social Security benefits may be taxed, and RMDs are taxed at the ordinary income tax rates,” says Wertheim. “Deferring your distributions as long as you can makes sense from a tax perspective, but how long you can defer will depend on your retirement income needs.”

Capital gains are another factor to consider. If you sell a capital asset, you’ll need to pay capital gains taxes on the profits. Capital assets include stocks, bonds, real estate, coin collections, jewelry, and digital assets like cryptocurrencies.

Long-term capital gains tax rates are set at 0, 15, or 20 percent and apply to any investment owned for more than one year. Short-term rates are determined by a taxpayer’s ordinary income tax bracket and apply to assets owned for less than a year. This means long-term rates will be lower than short-term ones.

“There are multiple tax strategies that can help you take advantage of lower capital gains tax rates,” says Wertheim. “But mostly, you want to make sure you are being strategic about when you sell your capital assets so that your profits from the sale don’t unintentionally bump you into a higher tax bracket for the year.”

Capital gains can also increase Medicare premiums. “If you have a higher income year—for instance, because you’re selling real estate or some other large asset—pay attention to your Medicare premiums,” she says. “The Medicare system may automatically assume this new, higher number is now your regular yearly income.”

Wertheim recommends people pay attention to state tax rules as well. “There may be nuances at the state level that also allow for specific tax planning,” she says. “In particular, it’s important to understand how retirement income is taxed in your state before finalizing your financial plan.”

For example, Jacobson says, “Retirees can deduct between $20,000 and $24,000 in retirement income from state taxes in Colorado, depending on their age.” This means income from Social Security and pension plans may be mostly or entirely state-tax-free for many Colorado residents.

Give Strategically

Once you start taking RMDs, you may find yourself in a higher tax bracket. One way to minimize the tax consequences of a higher income is through a qualified charitable distribution (QCD). A QCD is a tax-free donation directly from your IRA to a qualified charity. Although there’s no tax deduction for these donations, making a QCD can reduce your RMD in a given year without boosting your overall income.

“In 2024, anyone over 70 1/2 can contribute up to $105,000 directly from their IRA to a qualified charity,” says Jacobson. “This can help you meet your charitable goals and simultaneously meet your annual RMD. Plus, you don’t get taxed on it! It’s a triple win.”

“Giving to a 529 education fund is another way to satisfy a gifting goal, and you’ll typically get a state tax deduction,” says Jacobson. “We used to advise against this strategy because it sometimes affected financial aid eligibility for the recipient, but the rules have recently changed. Now, it makes more sense for more people.”

Another option to mitigate your tax bill is to use a donor-advised fund (DAF). This is a charitable investment account that lets you donate cash, securities, or other assets to qualified public charities.

“If you contribute to a donor-advised fund at about the time you retire, you can claim a federal income tax deduction for the year in which you make the donation,” says D’Unger. “Later in retirement, if you sell a capital asset, a DAF can also help you avoid the capital gains tax that would be due on the sale.”

“Taxes are inevitable,” says Jacobson. “But they can be managed. Having a retirement income plan that accounts for taxes can make your tax bill more predictable. It can give you confidence to spend what you’ve worked so hard to save.”

Written By Neil Downing

What is the actual value of a dollar? The obvious answer is 100 cents. However, this purely financial assessment fails to account for emotional attachment. There are, essentially, four different types of dollars investors encounter, and each has a different emotional value. Failing to understand the differences among the four has disrupted many well-designed investment plans.

Theoretical Dollars

The first type of dollar is one that investors often meet at the beginning of their investment journeys. These are purely theoretical dollars. They exist only in statistical models. Still, they’re important because they help establish expectations for long-term returns and short-term setbacks that could happen along the way.

Theoretical dollars are the foundation of all strong investment programs and financial plans. Using complex modeling tools and customized investor data, advisors can demonstrate a range of future outcomes that shift, depending on interim inputs. The future net worth they estimate, minus your net worth today, is composed entirely of theoretical dollars. At best, these dollars have no emotional value. At worst, they can be misleading—especially if we let ourselves get emotionally attached.

It’s difficult for the human brain to forecast feelings of loss. Visualizing joy is much easier. That’s why, although we often underestimate how we will feel after a surprise market dip, we can easily slip into daydreams about spending our theoretical dollars at age 70, when we’re on a beach somewhere with our loved ones.

Theoretical dollars are important, but keep in mind, they are not real.

Statement Dollars

As investors successfully navigate their journeys, theoretical dollars gradually become statement dollars. These are real dollars, built by discipline, sacrifices, and time. But they are invested, illiquid, and hopefully, growing. The effort required to accumulate these dollars creates a connection that gives them emotional value.

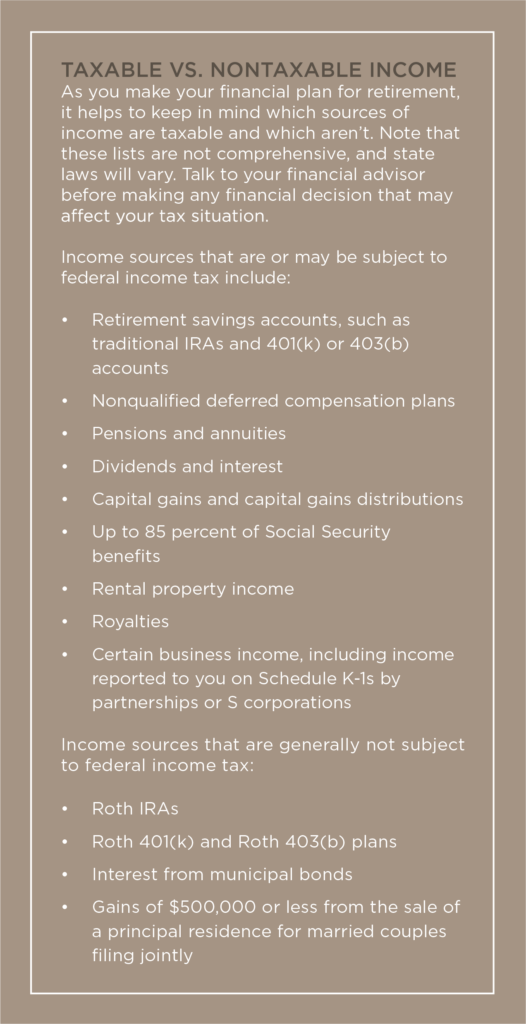

Statement dollars are like a scoreboard—one that can be checked every day. Their emotional characteristics are driven largely by two conflicting definitions of success: absolute success and relative success. Absolute success means setting a clear, immovable objective like a specific dollar amount or percentage growth. If portfolio returns exceed this objective, the investor can declare victory.

Relative success means evaluating portfolio performance compared to a similar portfolio or benchmark. For instance, many investment portfolios aim to outperform the S&P 500 Index. If the S&P 500 falls 2 percent, but the investor’s portfolio falls only 1 percent, this is considered a relative success. Because relative success has no absolute requirements, it can be measured in both up markets and down markets. However, it is important to remember the old Wall Street proverb that “you can’t eat relative performance.”

Both measures of success carry emotional risk because it’s human nature to want to outperform. A truly emotion-free portfolio—one that delivers absolute success in down markets and relative success in up markets—exists only in theory.

It doesn’t matter how much statistical modeling we do. Nothing can replicate, and no one can avoid, the emotional value of statement dollars. But each investor’s time horizon often determines how much emotional value they have. Thus, one piece of a financial advisor’s job is to keep investors focused on the long term. Like a fisherman pitching and rolling in a boat, watching the horizon can stabilize perspective.

The Spendable Dollar

Once a statement dollar is deemed spendable, its emotional value climbs dramatically. Statement dollars can rise and fall, but the spendable dollar (also known as cash) is king.

People feel real emotional pain when separated from their spendable dollars. That’s why the government withholds taxes before paychecks can be cashed. It’s why casinos use chips instead of real money. And it’s why companies encourage saving via payroll deductions. Once we feel a sense of permanent ownership over our spendable dollars, they’re much harder to let go of.

From an investment perspective, the emotional impact of a spendable dollar is often seen when an investment distributes income. Income is the least tax-efficient way to grow wealth, and taxable investors should nearly always choose unrealized gains instead.

Most investors view unrealized gains as statement dollars until they are sold or withdrawn. Then, they become spendable dollars and may feel more permanent.

While income-producing strategies can be an important part of a well-diversified portfolio, overexposure or a premature conversion of statement dollars into spendable dollars (like selling stocks) can significantly reduce the portfolio’s long-term value. Yet, the comfort of watching a spendable balance grow can tempt even the savviest investors.

The Spent Dollar

Generally, there is only one definition of a spent dollar. It is a spendable dollar we used to own, and now we don’t. This can be highly emotional. When dealing with spent dollars, investors often lose rational perspective.

Of course, not all spent dollars have the same value. We enjoy spending when it is voluntary and rewarding but usually not when we are forced to spend money on taxes, speeding tickets, or insurance premiums. These dollars often carry a sense of loss, and we commonly resist spending any dollar that has been hard-earned, diligently saved, or long-awaited. This resistance can lead investors to make imprudent investment decisions, but it typically makes an even bigger impact on planning.

Even if a strong foundation was established via theoretical dollars, the emotional roller coaster of statement dollars was successfully navigated, and the conversion to spendable dollars was perfectly planned, there is always a heightened sense of doubt when turning a spendable dollar into a spent dollar.

Why? Throughout the other three phases, time generally rewards you, healing wounds, providing flexibility, increasing options, and maximizing the power of compounding. But a spent dollar reverses the clock, turning time into an adversary by reducing future options. Nothing feels more limiting than a permanent decision, and spent dollars are spent, forever.

Navigating Emotional Values

Investing is emotional because saved money and long-invested assets often require sacrifice, patience, and persistence. These emotions can be clearly defined, and even predicted, but rarely avoided. To push back against the natural cognitive tendencies that lead to emotional decision-making, consider these four suggestions.

Be wary of using theoretical dollars to define risk tolerance. A risk profile that feels right with theoretical dollars will inevitably feel wrong when hard-earned statement dollars decline in value.

Attempt to prioritize which definition of success is most important to you, then manage statement dollars accordingly.

Try to resist the allure of spendable dollars from cash distributions. Even if they are reinvested into statement dollars, some portion will be spent on taxes. If they aren’t reinvested, you could miss out on future gains and still have to pay taxes.

Finally, when it is time to spend, spend. Enjoy the rewards of a successful investment journey.

The fear of running out of money is real and powerful. Consequently, many retirees fail to fully capture the value of their prudent historical decisions. A financial plan is a critical piece of the investment journey not only because it helps build wealth, but also because it can give you permission to enjoy what you’ve constructed. Remembering the differences among these four types of dollars can also be helpful, especially if it helps us mitigate our natural emotional connections.

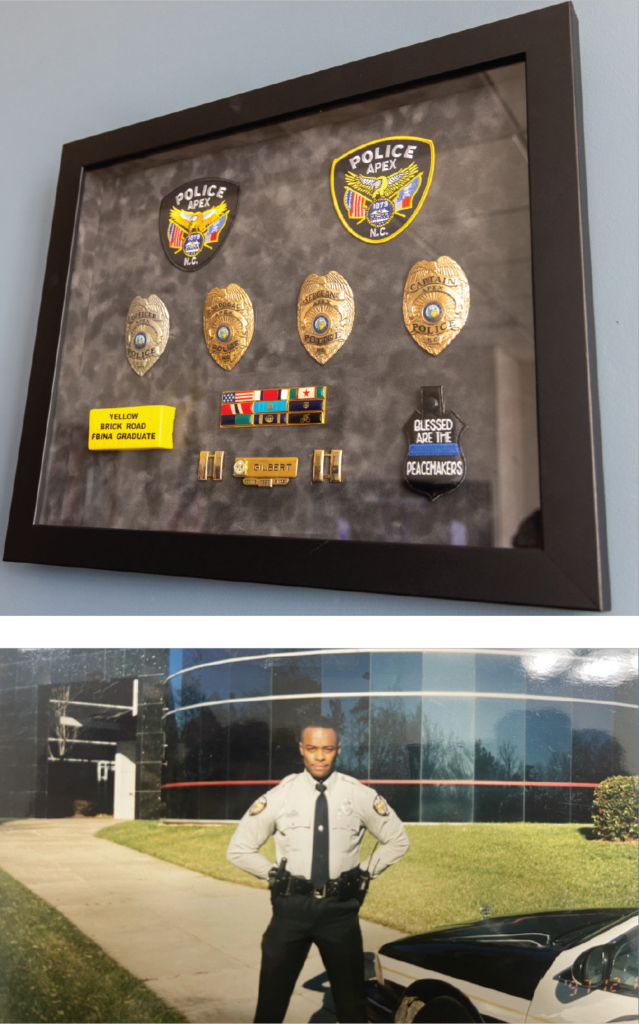

In 2019, Gilbert cleaned out his locker at the Apex, North Carolina, police department and officially retired from what he calls a highly unlikely 29-year career in law enforcement. Gilbert grew up in a culture where people distrusted and sometimes disliked police officers. Yet by all measures, he’d become a hugely successful one.

After a lifetime in the force, he put his uniform and badge away, turned off the lights, and walked out the door into charming, historic downtown Apex. “It’s been a great ride,” Gilbert wrote at the time. “On to my next assignment.”

This sign-off, he says, contained a hidden message. Gilbert was about to do something he once thought was even more unlikely than becoming a police officer. Seven months later, he was elected mayor.

Gilbert, now 54, grew up in Apex. His neighborhood, Justice Heights, was on the other side of what he says was a clear dividing line marked by State Highway 55. Most Black people lived on one side, he says, and people on the other side didn’t see the neighborhood or the people who lived there as part of their town.

Now, Apex is different—more diverse, more developed, and much larger. In 2023, the town’s total population was 77,000. In the 1970s, when Gilbert was a child, it hovered around 3,000.

Gilbert lived in public housing, where he witnessed repeated hardships in his community. He had friends and relatives who got in trouble with the police. Although he never had any personal run-ins with law enforcement, he got the message that police officers were not to be trusted. He certainly never dreamed of becoming one.

When Gilbert graduated from high school in 1987, he went to work as a water meter reader for the nearby town of Cary. “It was just a job,” Gilbert says, and he wanted something that felt meaningful.

“A friend of mine became a police officer,” Gilbert says. “At first, I thought, that’s not for me. In the community where I was raised, being a police officer, that’s not what we do. It’s not who we are. But my friend kept sharing all the great things he was doing, and it just really intrigued me.”

Gilbert let his curiosity lead the way, enrolling in criminal justice courses at a community college and working his way through the North Carolina Coastal Plains Police Academy. After graduation, he says, “Everything just started opening up.”

In 1990, Gilbert joined the Apex Police Department, eventually becoming the town’s first Black police captain and later graduating from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) National Academy.

Suggesting Solutions

His path toward becoming an elected official began by responding to a noise complaint. A teenager was annoying neighbors by doing skateboarding flips in his driveway. Gilbert found the teen, whom he recognized as part of a local skateboarding group that often got in trouble around town.

He told the young man, Tracy Stallworth, that he would have to stop. “He looked at me and said, ‘I can’t skateboard in my own driveway?’ And I said, ‘Nope.’ So, he picked up his skateboard, walked in his house, and slammed the door.”

Gilbert drove a few blocks away before he realized he had missed an opportunity. “I hadn’t offered him any solution,” he says. Gilbert was troubled by what felt like an unfair outcome.

So he rekindled the conversation with Stallworth, and they started dreaming of solutions. Their biggest idea was a downtown park where skateboarders could practice and hold competitions or events without disturbing neighbors. But a skate park seemed impossible at first.

In the meantime, as police captain, Gilbert helped organize weekend skateboarding events for the community—a short-term solution that often drew more than a hundred skateboarders and spectators of all ages. Over time, momentum for a skate park grew. Stallworth’s skateboarding friends helped raise funds and community support.

Making it real meant asking the town council for a significant amount of money, Gilbert says. “One night, they all skated to a town council meeting, and we filled the council chamber,” he says. Three of the skateboarders spoke, showing their enthusiasm and the growing demand for a safe skateboarding space.

The council saw their vision and, at the next meeting, approved $750,000 in funding—a huge amount, especially for a relatively small town. The council asked Gilbert and the skateboarders to raise another $250,000. With the help of a local benefactor, they did it.

Since it opened in summer 2015, the Rodgers Family Skate Plaza—often called Trackside because of its location between two historic rail lines—has become one of the most popular gathering spots in Apex. For their efforts, Gilbert and Stallworth were invited to the White House, where they received a Champions of Change award from President Obama.

Stallworth, now 28, says he was awed by the energy and passion Gilbert gave to the project. “Jacques, who had never skated a day in his life, put almost a year into this thing,” he says, and in the process, inspired Stallworth to show up and be a leader himself. Stallworth now gives free skateboarding lessons to kids. He wants to pay forward what he learned from Gilbert.

The skate park project got Gilbert thinking too. “If a young police officer, just a shy kid from the ’90s, can end up at the White House, perhaps he can inspire others to show up where they’re not invited,” he says.

Why Not You?

In Gilbert’s mind, becoming an elected official was farfetched and improbable. Community leadership didn’t feel like it was open to people from his background, and he had little understanding of what those jobs entailed. But others saw his potential.

Nicole Dozier, a local health policy advocate, says she was attending regular town meetings back in 2013, when Gilbert and Stallworth were campaigning for the skate park. She was there the night the skateboarders filled the chamber, and she was impressed. Later, Dozier became a town council member and served eight years as Apex’s mayor pro tempore.

During her second campaign, she says, she heard Gilbert was approaching police force retirement and asked him if he might consider running for office. “I thought he could be really inspiring,” she says. “People liked him so much.” Gilbert’s first response was, “Absolutely not.”

He was already focused on another big project: the Blue Lights College, a post-high school program for young people considering police careers. Gilbert was also busy training new officers, coaching youth basketball, and teaching self-defense classes. He likes to stay busy and meet as many people as he can.

One of the people he met was Jennifer Kopras. At the time, Kopras was 46 and hoping to fulfill her lifelong dream of becoming a police officer. Now, she’s a Blue Lights College graduate and has been a part of the Apex police force for more than a year. She says meeting Gilbert was a big part of her journey.

“Jacques sees a spark in someone and ignites it,” Kopras says. “He saw something in me and helped me follow my dreams. He gave me a little more hope to push through.”

Dozier saw a similar spark in Gilbert and kept encouraging him to run for office. “At some point, he finally said, ‘OK, I’ll think about it,’” she says.

A few months later, Gilbert was watching Apex’s annual State of the Town address when he says he heard a voice in his head asking, “Why not you?”

He went home and talked to his wife Meshara; daughter Kalabria, now 27; and son Logan, now 21. They loved the idea. “My son said, ‘You’re already the mayor! You just don’t have the title yet.’” Kalabria, a public relations professional, signed on as his campaign manager. With his family behind him, Gilbert felt confident and capable.

Stallworth says he heard the news through the grapevine and was glad but not surprised. “It just made so much sense,” he says.

A Golden Year

Gilbert is now in his second term, after winning an unopposed election in November 2023. Since he was first elected in 2019, his list of wins includes writing the town’s first-ever 10-year strategic plan, negotiating tens of billions of dollars of deals with big and small businesses that are relocating to Apex, instituting diverse holidays and better benefits for town workers, and leading the town through the intense period of COVID-19 shutdowns and racial unrest that have defined the last few years.

Throughout, he has maintained his focus on providing solutions and building community.

Dozier says at the height of the pandemic, when schools were holding all events outdoors, she ran into Gilbert at her daughter’s prom, wearing what by then had become his trademark gold-toned shoes. “He says he wears those golden shoes for golden moments,” she says.

Online, there are pictures of Gilbert wearing the shoes at the opening of a park, a community event at a local mosque, a dance contest to benefit people with disabilities, and a party celebrating the town’s 150th birthday. He says he hopes the gold shoes make him feel approachable so people won’t feel intimidated to talk to him. They’re one small part of his overall strategy to listen, learn, and provide solutions.

Gilbert says he wants residents of Apex to know that he is there for them. At its core, he says, the role of mayor is not so different from that of a police officer. “Our campaign slogan was ‘People First,’” he says. “And that’s how I look at everything. It’s always about the people.”

The difference is, as a police officer, Gilbert was often working reactively, responding to a crisis or an isolated incident after it happened. As mayor, he can strategize and be more proactive. He can get closer to the root of things.

Supporters say Gilbert’s charisma is contagious, and the changes he’s making are genuine—a direct result of what he hears from his constituents. Officially, “it’s a part-time gig,” he says. “But for me, it’s a full-time job.”

“Jacques’ purpose, you can see clearly, is to help others,” Kopras says. “There is no rank with him. We are all equal. You can tell he doesn’t see himself better than anyone else. […] If we could mold him and create others like him, the world would be an incredible place.” Gilbert says he is especially proud that, under his leadership, Apex has increased its efforts to include and celebrate its Black communities. “We’re formally celebrating Juneteenth now,” he says. “And that was never the deal before. A walk for Martin Luther King Jr. Day? We never had that.”

With Gilbert’s influence, the entire town calendar has become more diverse. Apex now officially celebrates Pride Month, Hispanic Heritage Month, Hanukkah, and more.

While Gilbert speaks out on issues from traffic to housing to policing, his main job, as always, is showing up. Whether it’s a ribbon-cutting event, a town festival, or a football game between two rival high schools, he’s almost certainly going to be there.

And every Friday, he shows up somewhere in the town to knock on doors and ask people what they need from their local government. He includes town employees in these rounds.

“People get so laser-focused on what’s happening on Pennsylvania Avenue,” Gilbert says. “But when we ask them what we can improve on Salem Street [Apex’s main street], they know what we need. A pothole that needs fixing has no political affiliation.”

During his police force career, Gilbert says, he was often called to help people on their worst days. As mayor, he gets to be there for some of the golden moments too.

Written By Kim Painter

Succession planning is an important part of running any business, especially a family enterprise. Less than one-third of family businesses survive into a second generation, and only about one in 10 continue through a third generation. Success often depends on how well the business and family have prepared.

As part of the succession planning process, you may want to consider centralizing your finances so your family can access all your financial information in one place.

One way to do this is to establish a family office, which is a formal business entity created to manage your family’s wealth. Another, more informal, approach is to work with a team of advisors who provide family office services. Typically, this team is led by a financial advisor and includes tax professionals, estate planning attorneys, banking professionals, and others.

Family office services can include multigenerational wealth and estate planning, coordinated tax planning and compliance, insurance and investment advisory, family governance, consolidated reporting, bill-paying solutions, and more. Depending on your needs and goals, your team will provide a unique mix of these services that adjusts as your family and business evolve.

Regardless of which approach you choose, look for a firm with specialized expertise. A successful leadership transition will require careful planning, reliable governance, next-generation leadership education, and effective operational structures. With those pieces in place, your family can feel confident and prepared to continue your legacy.

The Deals enjoy their 3,500-square-foot vacation home, which sits on 119 acres near Sylva, North Carolina, for weekend getaways and as a place where their family can gather for holidays and vacations.“The property is gorgeous, and the views are spectacular,” says Steve, 63, a gastroenterologist. “We’ve got trails to hike, and the cute little mountain town of Sylva is only about 10 minutes away.”

The Deals have three adult children and, so far, four grandchildren, all under three years old. “One day, we plan to host Grandpa and Grammee Camp for the kids,” says Mitzi, also 63, a retired schoolteacher.

“My goal is that my grandchildren will grow up playing together at the house, creating ties that bring them back,” says Steve. “I want them to have great memories growing up with their cousins.”

The property’s location works well for most of their family. The Deals can drive to Sylva in less than three hours. Their two daughters’ families live just a little farther away. And their son and his wife, who live in Miami, drop in as often as they can.

While drafting their estate plan, the Deals discussed several ideas for handing down the house, then decided to let their kids take part in the conversation. “We talked to our children and asked if the mountain house was something they wanted to keep when we are gone or if they wanted us to get rid of it,” says Steve. “The consensus was they wanted us to keep it.”

Like the Deals, many people hope their vacation properties will become a part of their legacy: a place to enjoy with family and friends now and somewhere their children and grandchildren can find comfort in the future.

Assessing Your Estate Plan

People are often deeply passionate about their second homes, whether that home is a cottage on the beach, a lodge in the mountains, a farm in the country, or a cabin on a lake. That passion can sometimes cloud their decisions about how to include the property in an estate plan, says William Blair, a CAPTRUST financial advisor in Charlotte, North Carolina. William helps his clients navigate these and other estate planning decisions.

“My goal is not to influence how clients structure their estate plans but, rather, to help them understand some of the unforeseen consequences that can arise from certain strategies,” he says. “A great estate plan considers the needs and circumstances of the beneficiaries and the nature and complexity of the assets.” Mike Blair, another CAPTRUST financial advisor and William’s father, agrees.

Mike says more than half of his clients own second homes, and a few have two or three vacation properties. “Everybody wants their grandchildren to grow up together so that first cousins and second cousins have shared family memories,” he says. “It was easier in the past when people lived closer together, but now they often come together only for vacations.”

Keeping the Peace

When deciding what to do with a second home, Mike says parents should ask themselves if leaving the property to their children will mostly improve or complicate their children’s lives. Do the kids want this home, or would they prefer to have the proceeds from its sale?

Passing down a vacation property can give your family roots, he says. “But the risk is that it can also create family drama. If you think that could happen, you may need to sell. It’s not worth fraying relationships.”

Most of the time, Mike says, things go smoothly, and parents typically have good intuition about how their second homes will impact family dynamics. “I’ve been doing this for 35 years, and there have been very few situations where it has gotten bad,” he says. “We try to deal with things before anyone can get terribly upset.”

Both Mike and William frequently talk to clients about ways to pass down their second homes. “Family is important to people,” William says. “The last thing they want to do is create conflict with the people they love because of their estate plan.”

What Heirs Can Expect

To reduce conflict and make sure heirs are aware of what ownership entails, William suggests clients talk with their family about what’s required to maintain the property. “Most of the second homes our clients own are not revenue producing. There are property taxes, insurance, and maintenance expenses, and those can be high.”

There’s also time required for upkeep. “For many second homeowners, the time spent maintaining their home is a labor of love rather than a chore,” William says. “Their children may not fully understand the significant time required to maintain it. Additionally, when property ownership is shared among several people, the division of these chores and the burden of the maintenance costs can create rifts.”

Some heirs don’t think they’ll use the residence often. For instance, an adult child living in California might not want to spend their vacation time going to a beach house all the way in Georgia. But their siblings who live closer might use it more frequently.

“It can cause friction if one of the adult children barely gets to use the house but is still asked to cover an equal share of the expenses,” William says.

In other cases, heirs might not be able to afford to contribute. “We have one client who has a beach house where they spend a lot of time with their family,” William says. “Their adult children love the house, but they have very different financial situations and incomes right now.” The parents are concerned that if they leave the house to all three children, the kids may not be able to contribute equally.

“We also see significant conflict among adult children when they disagree about who can use the house when, who should pay for which expenses, and whether the house should be used for different activities, like parties or rentals,” William says. For instance, should the house be available for public rental when it’s not in use by family members? Should friends be invited? And if so, can they bring pets?

Honest conversation and group planning can help avoid these problems. “I had a client with a mountain home that had a spectacular view,” Mike says. “Only one adult child could afford to maintain it, so the family agreed that she would inherit the vacation house, and her two sisters would inherit the parents’ primary residence.”

The father asked his daughter who received the mountain house to give her sisters at least one week there each year. “It wasn’t a requirement,” Mike says. “It was a request.”

Paying It Forward

Some clients also choose to set aside money in their estates to pay for second home maintenance, says attorney Todd Stewart, managing partner at Stewart Law P.A., also in Charlotte. “Almost all of the time, when people want to keep the home long term for their family, we talk about some sort of endowment to cover the necessary expenses, including tax bills, insurance, and maintenance,” he says.

Stewart works with one client who has two vacation properties—one at the beach and another in the mountains. This client plans to create a foundation that will turn his mountain property into a camp for kids. The beach house will be left to his children, with funds allocated for taxes and maintenance.

Stewart says most of his clients put their vacation homes into revocable living trusts. The trust holds ownership for the beneficiaries, usually the family. The clients have control over the property during their lifetimes, and the beneficiaries inherit the home when the client passes away.

The advantage of using a revocable living trust, instead of a will, is that the trust removes the home from court supervision and its associated costs and delays, Stewart says.

“An irrevocable living trust is another option and comes into play when we think the estate is large enough to be subjected to estate taxes,” Stewart says. In this case, the property’s value is based on the time when it is transferred into the trust, instead of years later when it may be worth more. “It takes the property out of the taxable estate,” he says.

Some people choose to place their second homes in a qualified personal residence trust. This tax-advantaged strategy allows the home to pass to the beneficiaries for less than its full economic value, Stewart says.

Another option is to put the property into a limited liability company (LLC). “The two main reasons we use LLCs for homeownership are liability protection and convenience in gifting,” Stewart says.

Liability protection is important if the home is going to be used for third-party rentals and there is a risk of lawsuits due to fire, theft, or injury.

“Sometimes, clients use an LLC to transfer ownership of the property to their heirs over time,” Stewart says. “Every year, the owner can transfer shares of the residence to their beneficiaries while still maintaining control.”

Planning for Different Options

The Deals have tried to plan for a variety of scenarios for their mountain residence. The home is now in an LLC, and at their deaths, it will roll into a revocable living trust.

“We are leaving money in the trust to help care for the property, so the upkeep won’t be a burden for our children,” Steve says. “We made it so that, if they decide to sell it, they can, because we don’t know what’s going to happen in the future or where they are going to be.”

The Deals recently renovated the house, hiring an architect to create a more open floor plan so the family could be together in one room. They also added lots of windows to frame their wide mountain views. The house has a yard, a fire pit, a terrace for grilling, and a huge picnic table that seats their entire family of 12.

“Our intention is that it’s comfortable,” Mitzi says. “We have the world’s biggest sofa in the family room. Three people could sleep on it.”

“Having the whole family together is magical,” Mitzi says. “It’s a dream come true.”

Since their family may continue to grow, the Deals considered building a bunk house out back, but their children said they’d rather have an addition to the existing home, Steve says. “They told us, ‘We don’t want to be in separate houses. We want to be all together.’”

Steve and Mitzi were pleased to hear that. “It means they treasure the time together as a family as much as we do,” Steve says.

Written By Nanci Hellmich

Trivia pro and quizmaster Paul Paquet, author of The Brain Boosting Trivia Book for Adults, is one of those people.

“I’ve always had an absolute love of learning,” says Paquet, 58, of Ottawa, Ontario.

Over the past 25 years, Paquet has written more than 135,000 trivia questions across a variety of media: TV shows, books, apps, the board game Trivial Pursuit, and his website, triviahalloffame.com. He also qualified to appear on Jeopardy!

“I find it interesting to sit down and memorize things like the Chinese dynasties,” says Paquet. “Some people have different memory skills. My brain is wired to memorize facts.”

He’s quick to add that he’s not good at everything. “I’m terrible at fixing things around the house,” he says. “I often joke that if the apocalypse comes, I know who is going to be needed to rebuild society and who is going to be zombie food. I am going to be zombie food.”

Still, there are advantages to knowing a lot of trivia. It’s a conversation starter, stimulates your mind, and provides hours of free entertainment at social events, parties, and family gatherings.

Paquet says his wealth of knowledge comes in handy. Once, when entering the U.S., he told the customs agent he was going to attend a trivia event, and the officer quickly asked, “What are the four state capital cities named after U.S. presidents?”

At first, Paquet thought the agent doubted the purpose of his trip, so he quickly rattled off: Jackson, Mississippi; Lincoln, Nebraska; Jefferson City, Missouri; Madison, Wisconsin. “I realized after I got the four of them correct that he didn’t care. He was just making conversation.”

Developing an Enquiring Mind

Paquet began sharpening his trivia skills at a young age. “I was the weird kid who would read the World Book Encyclopedia,” he says.

In grade school, he would sometimes hang out with the recess monitors. “I would quiz them on what I had read,” he says. “At first, they thought I was just a curious kid. Then they realized I was quizzing them on the encyclopedia.”

In 1982, he appeared with his high school team on Reach for the Top, a Canadian quiz program. His team won twice.

When he was in his 30s, he started taking the qualifying test for Jeopardy! “I did well enough to make the live auditions three or four times, but I wasn’t ever picked,” he says. “My wife, Laura, who also loves trivia, was on the show in 2004.”

Creating the Best Questions

Over time, Paquet turned his interest into a career. In 1998, he started the Ottawa Trivia League, running events at local pubs. Bars pay him to write questions and provide hosts for trivia nights around the city.

One heartwarming outcome of his work: Several couples have met at his trivia events and fallen in love. “It’s a real rush to know there are human beings who wouldn’t be here if their parents hadn’t met answering questions about Taylor Swift.”

He launched his website in 1998. People can order questions in bulk for apps or pub trivia leagues. The pub nights and website “both took off and grew in their own directions,” he says. “It became a full-time job and still is.”

Paquet, who writes about 15 questions a day, is always searching for new material. “I wander around Wikipedia and read The Economist a lot,” he says.

Writing good questions is important to his business. “The content of the question is also the marketing of the business,” he says. “If people show up for trivia night and feel dumb and left out, that’s my failure.”

“My goal is for the questions to be entertaining,” says Paquet. “I throw clues in so that people can figure out what the answers are.” He wants to bring out the best in his audience so that participants will say to themselves, Oh, I had that board game when I was six, or I loved that song when I was 20.

Many of the people who attend Paquet’s trivia events are 20 to 30 years younger than he is. “It would be easy for me to ask questions about Talking Heads or All in the Family, but now I get to learn about Doja Cat and all the new video games out there,” he says. “People respond to that well.”

Players tend to be best at trivia when answering questions about subjects they care about. “Sports trivia people are the very best because they have so much fun with it,” says Paquet.

He advises trivia players not to take each question so seriously. “When you make a mistake, forget about it and move on,” he says.

“It doesn’t matter how good you are. There are times when something you know well hides in your brain and will not come out,” Paquet says. “You could stump Ken Jennings [the host of Jeopardy! and the highest-earning American game show contestant ever] if you ask him the right question.”

Continuing to Learn

Paquet still works to get better at remembering facts, and he says others can do the same.

The secret to his success is based on concepts from the Ebbinghaus forgetting curve, named after German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus. The curve is a graphic representation of the forgetting process, illustrating how information is lost over time when there is no attempt to retain it.

“The idea is, the more often you see a fact over time, the longer you’ll remember it,” says Paquet. “If you see a fact once, you may remember it for a short time. If you see it again, you will remember it longer. If you see it again, you will remember it for even longer still.” Some studies suggest a person needs to revisit the same fact at least seven times before it becomes permanent.

To put this into practice, Paquet uses the Leitner system. That is, he studies facts on flashcards kept in an elongated box, similar to a recipe box. He moves the flashcards to different compartments of the box after he reviews them.

“I’m writing cards every day,” he says. “It’s the reason I’ve gotten better in the areas where I was weak, like the Bible, classical music, and Broadway musicals. It has made a huge difference.”

Paquet also tried the AnkiApp, a cross-platform mobile and desktop flashcard app designed to help with learning. He says the app works well for lots of people, but he prefers the Leitner box. “I’ve been able to absorb much more than I would otherwise,” he says. “I train, in a sense, and I have fun doing it.”

When he’s training, Paquet says, “I can practically feel the synapses in my brain lighting up and making connections. I can’t say if I’m staving off dementia, but I do feel sharper now than I did 25 years ago.”

Research from the National Institute on Aging says Paquet could be onto something. There is evidence suggesting cognitive training might help delay or slow age-related cognitive decline. Cognitive training involves structured activities designed to enhance memory, reasoning, and speed of processing.

“If the 58-year-old me and 26-year-old me were doing a head-to-head contest, I’m pretty sure the 58-year-old would win,” he says. “I might not be as fast at remembering facts, but I do feel like I know more than I did.”

Written By Nanci Hellmich

But, Maier says, one of the best things about dance is the way it challenges her brain. “There’s always more to learn,” she says. “There’s always room to grow.”

Maier’s experience aligns with what researchers have learned about dance over the past few decades. It’s more than just a pastime or another form of exercise. From waltzes and tangos to hip-hop and country line dancing, dance has superpowers. In short, the Bee Gees were probably right: “You should be dancing.”

Why Dance?

“The secret sauce about dance is that it’s a complex activity,” says Joseph Verghese, a professor of neurology and medicine at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York.

“The three main ingredients are that it has a mental component, it has a physical component, and it has a social component,” he says. Each of these, individually, has been shown to have profound effects on cognition.” Additionally, research suggests the combination of these ingredients may be greater than the sum of its parts.

Body Benefits

Like other forms of physical activity, dance builds muscle and bone, slows aging, enhances heart health, lowers blood pressure, and nudges cholesterol numbers in the right direction, according to the Harvard School of Public Health.

It also provides additional physical benefits that other forms of exercise can’t. For example, Verghese’s research shows that dance has a positive impact on stability in older adults. Other researchers have found that tango lessons specifically improve gait and balance in people with Parkinson’s disease—so much so that many people with the condition now make it a core part of their therapy.

By improving gait, stability, and balance, dance may also reduce the risk of falling. Falls are the number one cause of injury for adults 65 and older, and statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) say that falling accounts for roughly half of all accidental deaths in this age group.

Social Connections

Dance can strengthen a person’s sense of social connection, which can lower the risk of heart disease, stroke, dementia, and depression, according to the CDC.

“You generally don’t dance alone,” says Verghese. And dancing with other people adds something special. When you move in rhythm with others, you form an “active and dynamic bond,” he says.

Having the chance to connect with others is one of the reasons why dance is so fun. It also provides accountability—making dance easier than other exercise methods to consistently show up for. “Finding something enjoyable is key,” says David Marquez, a professor of kinesiology at the University of Illinois at Chicago. And the best exercise is one you will keep doing.

Emotional Rewards

Need a mood booster? Start dancing. In some studies, dance has generated good feelings more effectively and consistently than either yoga or team sports. It has also been shown to boost energy and confidence. When we dance, our brains get dosed with endorphins—the so-called happy chemicals that reduce anxiety, depression, and pain.

Science also confirms something Maier has observed. When she’s dancing, other cares slip away. “I don’t have time to think about problems at work or anything at all,” says Maier, who runs a fireplace business with her husband. “It takes all my mental and physical attention.” When she’s dancing, Maier can be present in the moment.

An Anti-Aging Superpower

If dancing was only good for your heart, muscles, mood, and social life, it would still be a very healthy activity. But dance may also offer something more: a way to fight age-related cognitive decline.

One of the first studies to prove this connection came from Verghese and his colleagues in the 1990s. It showed that people over age 75 who engaged in certain leisure activities were less likely than their peers to develop dementia. On the list were reading, playing board games, playing musical instruments—and dancing. In fact, dancing was the only physical activity associated with a lower overall risk of dementia. (It should be noted that some other studies show brain benefits from all forms of exercise, but findings remain mixed.)

In the two decades since this study, researchers have worked to confirm the special power of dance and have found promising results. For example, Marquez investigated brain health in middle-aged and older Latinos who take Latin dance classes, learning salsa, merengue, and other steps. “The most frequent benefits we see are for memory,” he says.

Marquez and Verghese also found that dancing seems to improve executive functioning, or the skills people need to plan and meet goals. In addition, in one recent pilot study of 16 people with early signs of memory loss, Verghese found less shrinkage in one key memory-related brain area in those who had been dancing for six months compared with those assigned to treadmill walking.

What these studies don’t show is why dancing has these possible brain effects. That the movement also involved music may be a contributing factor, but Verghese points out that his treadmill walkers listened to music too.

It does seem that “dancing requires more cognitive work” than other physical activities, Marquez says. “You have to move your body to the music and remember which steps come next. And when you’re dancing with a partner, you have to be aware and reacting and keep moving with your partner.”

People who take formal dance classes also keep learning new and more difficult steps and routines. “The brain is constantly challenged by change,” Verghese says. Maier agrees. She’s advanced through several levels of competitive dancing and intends to keep aiming higher. She’s inspired, she says, by fellow dancers in their 70s, 80s, and 90s. For her, she says, dancing “is a journey that is going to last forever because you can just keep learning.”

Written By Kim Painter

Guaranteed Investment Contract Investors Sue for Losses

Former employees of Bed Bath & Beyond (BB&B) lost approximately 10 percent of their guaranteed investment contract (GIC) investments when their 401(k) plan liquidated after the company’s bankruptcy. 401(k) plans typically offer at least one capital preservation option in their investment lineups—a GIC, a stable value fund, or a money market option.

BB&B’s plan offered participants a GIC that invested in intermediate- to long-term bonds. As interest rates rose in 2022 and 2023, the market value of the underlying bonds in the BB&B GIC fell below the book value. Usually, participants’ GIC accounts do not reflect market losses or gains and participants transact at book value (principal plus accrued interest). When there are market losses, the GIC’s guaranteed rate of return is adjusted downward over time to make up for the losses.

However, when BB&B declared bankruptcy, the GIC contract automatically terminated, so the investment was liquidated and paid to plan participants at the current market value. Because of the market decline, GIC investors were paid only about 90 percent of their accounts’ book value as reported before the plan termination.

Disappointed plan participants sued the plan’s fiduciaries and BB&B’s Chief Financial Officer. The GIC contract terms around plan termination are common and are not challenged in the lawsuit. What is challenged is the plan fiduciaries’ failure to take reasonable steps to mitigate potential GIC losses as BB&B’s fortunes dimmed.

According to the complaint, although the bankruptcy filing was made in April 2023, the company’s business struggles were publicly apparent as early as 2018 and 2019 when BB&B attempted a turnaround from declining performance. Had the plan fiduciaries been monitoring the potential investment impacts of a bankruptcy, they could have moved out of the GIC and into an investment that would not have been subject to such losses. It is not clear whether the plan fiduciaries would have made such a change. Until 2022, interest rates had been at historic lows for an extended period. If BB&B’s bankruptcy had not coincided with a rapid rise in interest rates, this would not have been such an issue.

This case is a good reminder that the guarantee in GICs, which are also sometimes referred to as guaranteed interest agreements or just guaranteed funds, applies only to the interest rate to be credited, not to the principal. It is also a reminder for plan fiduciaries to be aware of the potential consequences of broader corporate events on retirement plan investments. Harvey v. Bed Bath & Beyond 401(k) Savings Plan Committee (D. N.J. filed 9-14-23).

Fiduciary Potpourri

The following are real-life illustrations of ERISA’s fiduciary rules.

Not Following a Fiduciary’s Directions Is an Exercise of Discretion, Making the Directed Person a Fiduciary: A plan recordkeeper failed to follow directions in a timely manner to move investments in a 401(k) plan. The plan fiduciaries sued, alleging that the recordkeeper had breached its fiduciary duty to the plan. The recordkeeper denied liability, claiming that it exercised no discretion over plan assets and had no fiduciary liability. The recordkeeper asked for the case to be dismissed, but the judge refused. The judge observed that failing to follow directions of the plan fiduciaries was itself an exercise of discretion over plan assets, which resulted in the recordkeeper being a fiduciary to the plan. The case will move forward. Martone Construction Management, Inc. v. Thomas A. Barrett, Inc. (D. Md. 2023).

Retirement Plan’s Terms Cannot Circumvent ERISA’s Fiduciary Requirements: Janus Henderson, the investment firm, sponsors a 401(k) plan for its employees. The plan documents include a requirement that all proprietary Janus Henderson funds be offered for participants to invest their plan accounts. Non-Janus-Henderson funds could also be offered. The plan documents also provide that the plan fiduciary committee has no discretionary authority over the Janus Henderson funds. Rather, they could be removed only through a plan amendment by the plan sponsor.

Fiduciaries of the plan were sued for breaching their duties under ERISA by offering and not monitoring the Janus Henderson funds. Janus Henderson sought to have the case dismissed because they had followed the plan document in offering and not monitoring the Janus Henderson funds. The court refused to dismiss the case, noting that ERISA’s statutory duties to monitor plan investments override the plan document’s mandate to offer—and continue offering—all Janus Henderson funds. Schissler v. Janus Henderson U.S. (Holdings) Inc. (D. Co. 2024).

Duty to Monitor Investments in Limited Window of 300+ Funds: Until 2020, the Shell Oil Company 401(k) plan, with more than $10 billion in assets, offered a fund window with more than 300 actively managed mutual funds, in addition to target-date funds, indexed funds, and a separate self-directed brokerage account option. According to the complaint, the fund window included all actively managed funds offered by Fidelity, plus some other individually selected funds. Fidelity was permitted to add any new funds it released without any screening by the plan fiduciaries. The plan fiduciaries kept the investments in the fund window in place without any ongoing monitoring.

The plan’s fiduciaries were sued for failing to monitor the more than 300 actively managed funds in the fund window and failing to eliminate any that were not prudent. Seeking an early judgment, the plan fiduciaries argued that they met ERISA’s prudence requirements by coming to a reasoned decision that they were not required to monitor each of the funds. This decision was supported by advice from both internal and external counsel. The magistrate judge was unpersuaded, and the case will likely proceed. Harmon v. Shell Oil Company (S.D. Tx. 2023).

It is generally agreed that fiduciaries are not obligated to review the investments in a self-directed brokerage account option, or similar plan arrangement like a fund window, but only if the available investments are not too limited. For instance, is it not uncommon for a self-directed brokerage window to permit investment in all mutual funds, all mutual funds and exchange-traded funds, or all investments available through the self-directed brokerage provider.

In 2022, there were approximately 6,650 actively managed mutual funds in the U.S. Fiduciaries are not required to monitor more than 6,000 mutual funds if their self-directed brokerage account option includes all mutual funds. However, an issue arises when the available investments in the window are significantly limited. In that situation, plan fiduciaries may be responsible for ongoing monitoring of the investments—the core issue of this case involving 300+ investments.

Long-Term Incentive Plan Not Covered by ERISA—Usually: An employee was fired before she could accrue enough service to receive the maximum benefit under her employer’s long-term incentive program (LTIP). She sued, alleging a violation of the ERISA prohibition of plan sponsors from taking action to prevent plan participants from receiving benefits. The judge concluded that the LTIP was not covered by ERISA, so the case was dismissed. However, he observed that a bonus-type program, like the LTIP, would be covered by ERISA if payments under the program are systematically delayed to the termination of covered employment or beyond, or if payments are designed to provide retirement income. Faris v. Southern Ute Indian Tribe (D. Co. 2023).

Fiduciary Duty to Pay Only Reasonable Fees Includes Recordkeeper’s Indirect Fees from Managed Account Providers: In a groundbreaking decision, a Federal Court of Appeals has held that plan fiduciaries must evaluate the reasonableness of all fees received by their plan recordkeepers in connection with services to a plan, not just the fees paid directly to the recordkeeper. AT&T amended its 401(k) plan service agreement with Fidelity to add managed account services, which resulted in Fidelity receiving indirect compensation from the managed account provider, Financial Engines.

Under ERISA, it is a prohibited transaction to use plan assets to pay more than reasonable fees for services. Plan participants sued AT&T, alleging that the plan’s fiduciaries did not evaluate the reasonableness of the fees received by Fidelity after adding the managed account service. The district court sided with the plan fiduciaries.

However, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals reversed this decision, holding that all compensation received by the plan recordkeeper must be evaluated by plan fiduciaries. Bugielski v. AT&T Services, Inc. (9th Cir. 2023). This decision is at odds with decisions from the 3rd and 7th Circuit Courts of Appeals, setting up a likely appearance of the issue before the U.S. Supreme Court.

Flow of 401(k) and 403(b) Fee Cases Continues

The flow of cases alleging fiduciary breaches through the overpayment of fees and the retention of underperforming investments in 401(k) and 403(b) plans continues. Here are a few updates from the last quarter:

- Several cases were dismissed because they did not include sufficient allegations of fiduciary breaches. Others survived motions to dismiss and will proceed.

- One case involving a $1 billion plan was settled for $1.45 million. After attorney’s fees, the average participant will receive approximately $100.

- Another case involving a plan with approximately $1.3 billion in assets was settled for $6.75 million. After attorney’s fees, the average participant will receive approximately $265.

The low amounts awarded to plan participants in these settlements are the norm for litigation of this type. In contrast, the plaintiffs’ lawyers usually receive roughly one-third of the settlement amount.

DOL Focusing on Cybersecurity in Plan Audits

Recent plan audits by the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) include several information requests focused on cybersecurity. One recent request includes the following among a long list of additional items:

- Third-party audits of information technology systems, such as SOC 1 or SOC 2 reports

- The plan’s cybersecurity program, policy statements, and procedures

- Efforts to consider, address, develop, implement, or negotiate cybersecurity problems, procedures, or protections

- The plan’s cybersecurity breach response plan

- Cybersecurity awareness training

- Cybersecurity events, cybersecurity breaches, unauthorized access, or suspicious activity, and potential losses of plan assets because of these cybersecurity events

The above request may be part of an audit project to assess the current state of affairs in this area among plan sponsors. Regardless, plan fiduciaries should take reasonable steps to assess their vendors’ cybersecurity programs and document their assessments. The DOL’s “Cybersecurity Program Best Practices” document is a good starting point.

NOTE: Information on this page has been updated as of August 2024.

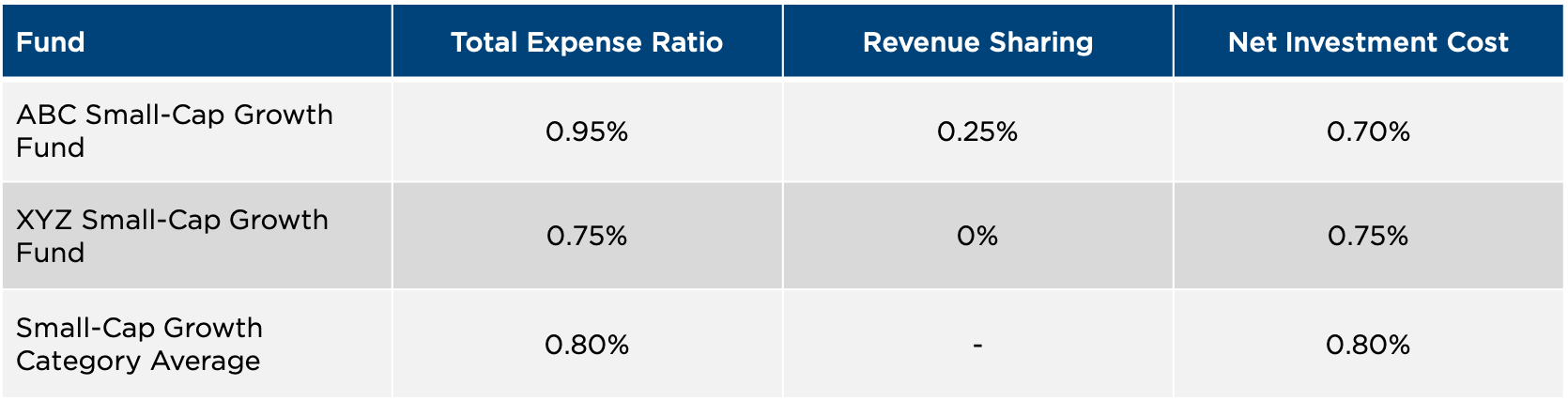

When it comes to fee benchmarking, most advisors and plan sponsors tend to think first about recordkeeping and other vendor costs. But investment fees are another important component of retirement plan fees. Retirement plan sponsors need to benchmark their plans’ investment fees to meet their fiduciary obligations. However, evaluating investment costs is complicated, and sponsors may encounter a series of common pitfalls. Here are a few to be aware of.

Benchmarking only the total expense ratio of the fund: A fund’s total expense ratio may not take into consideration all the components that comprise that fund’s true cost. This is particularly true for funds with revenue sharing.

Revenue sharing consists of fees built into the expense ratios of the plan investments. These fees are often used to offset plan expenses, like recordkeeping and administration. The amount of revenue sharing present within a fund’s expense ratio is a function of how the plan sponsor opts to pay for plan expenses. It is not directly tied to how much an asset manager charges to manage the fund. Recordkeeping and administrative fees are typically benchmarked separately by the plan sponsor.

Comparing the overall fund expense ratio without isolating the net investment fee component can result in a misinterpretation of benchmark results. Figure One demonstrates this concept.

Figure One: Understanding Total and Net Investment Costs

Source: CAPTRUST Research

IIn this example, the ABC Small-Cap Growth Fund has a higher total expense ratio than the category average and the XYZ Small-Cap Growth Fund. One could, therefore, erroneously conclude that its investment fees are high when compared to both. However, incorporating revenue sharing into the equation results in a net investment cost lower than both the category average and the XYZ Small-Cap Growth Fund.

Not considering investment fees in conjunction with overall investment performance of the fund: It’s important to evaluate investment costs in conjunction with fund performance. The Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) requirement for plan sponsors to determine that plan fees are reasonable is in consideration of the services received. In the case of a fund, the service received can be considered the fund’s performance relative to standards set by the plan sponsor. That’s why actively managed funds typically charge more than passively managed investments.

When funds are benchmarked, sponsors usually evaluate costs before performance standards.

It is important to remember that the lowest fee is not always the best value. The fund’s investment fees may be reasonable if, net of all fees, the fund is meeting performance standards set by the plan. This is true even if its net investment fee is higher than the appropriate category average. The determination should be made by the plan sponsor.

The takeaway: Benchmarking investment fees can be complicated, and it’s not always clear whether a fee is reasonable. Making an accurate comparison is sometimes harder than it sounds.

Like other plan fees, investment fees should be reviewed on a periodic basis. Plan sponsors should understand how the investment fees for their plan compare to alternatives in the market and in consideration of the services received.

In part three of this series, we dive into the revenue-sharing portion of a fund’s expense ratio and how share class selection can impact the method by which plan sponsors pay for plan expenses.

Legal Notice

This material is intended to be informational only and does not constitute legal, accounting, or tax advice. Please consult the appropriate legal, accounting, or tax advisor if you require such advice. The opinions expressed in this report are subject to change without notice. This material has been prepared or is distributed solely for informational purposes. It may not apply to all investors or all situations and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or instrument or to participate in any trading strategy. The information and statistics in this report are from sources believed to be reliable but are not guaranteed by CAPTRUST Financial Advisors to be accurate or complete. All publication rights reserved. None of the material in this publication may be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of CAPTRUST: 919.870.6822.

As of January 1, 2024, retirement plan sponsors can include such emergency savings accounts inside of their retirement plans.

The guidance provides important clarification on the administration of these emergency savings accounts, including the following:

- Employees must be eligible to participate in a plan’s PLESA if they meet any other eligibility requirements of the plan, such as age or service, and if they are not a highly compensated employee. For example, if a plan excludes collectively bargained employees, those employees can be excluded from participating in the PLESA as well.

- Automatic enrollment can be used for a PLESA. Also, if there is an auto-enrollment percentage of pay, it must be 3 percent or less.

- There can be no minimum contribution or balance requirement to open a PLESA. However, a requirement for whole-dollar contributions can be implemented.

- If the plan requires whole percentages of pay when making other types of plan contributions, that requirement can be applied to PLESAs as well.

- Contributions cannot be pre-tax. They must be Roth.

- Earnings do not need to be included in the $2,500 PLESA account balance limit. However, plan sponsors can opt out of a lower account balance limit or can impose a $2,500 limit that is inclusive of earnings. There is no separate annual contribution limit.

- Funds can be replenished up to the $2,500 limit (or a lower limit imposed by the plan) after a withdrawal.

- The same remittance timing rules that apply to elective deferrals apply to PLESA contributions.

- PLESA participants can withdraw funds for any reason. They do not need to prove an emergency to do so.

- Distributions must be permitted once each calendar month.

- The first four distributions per plan year are fee-free. Plan sponsors are not permitted to charge fees for subsequent withdrawals that would have the effect of making up for missed fees collected on the first four withdrawals.

- PLESA investments are limited to cash or cash-like accounts that do not have any liquidity constraints, including surrender charges.

- Sponsors must issue disclosures to all participants of a plan that offers a PLESA, including participants who elect not to participate. This disclosure can be combined with other required disclosures in the form of a consolidated notice. There is no model language yet, but the DOL may provide language in the future.

- Account statements are not required to include PLESA account balances, nor are 404(a)(5) investment disclosures required to reflect PLESAs. However, we expect many recordkeepers will voluntarily provide such information.

This guidance may be helpful to plan sponsors who are deciding whether to offer a PLESA, a standalone emergency savings account outside of the retirement plan, or both.

Still, some significant questions remain unanswered, including whether emergency savings account contributions are subject to annual deferral percentage (ADP) testing and whether non-ERISA plans can maintain PLESAs.

Plan sponsors who have questions about this or other SECURE 2.0 provisions should reach out to their financial advisor or visit CAPTRUST’s dedicated SECURE 2.0 Act web page.