A Lawyer’s Big Leap

“I opened it, and it said that I’d been admitted to Villanova Law School, which was a huge surprise to me since I hadn’t applied,” he says.

Dworetzky, who is now a second-career journalist for the Bay City News Foundation and a social and political cartoonist, had been telling people he was going to be a writer. And indeed, he had been writing since the age of about 16. There was just one problem. He was prolific and enthusiastic when it came to first sentences. After that, though, Dworetzky suffered from a lack of follow-through. He’d never actually written something that had an ending.

Dworetzky had no interest in going to law school. He didn’t know anything about it. He didn’t even know any lawyers. His father had asked him to take the LSAT before he left the country and, receiving Joe’s score in the mail, had taken it upon himself to fill out an application on his son’s behalf—essays and signature included.

Dworetzky didn’t give the offer much thought. He quickly wrote his father a note that said nope, not happening, and continued his travels. But by 1973, when he finally made his way back to Philadelphia, the thought of staying in one place and focusing on something interesting had gained some appeal. He agreed to try law school. For one week.

Many people who embark on a second career eventually look back and realize they never felt truly fulfilled in pursuit of the first. Their hearts were never fully in it, or they felt too afraid to go after their real passions. But Dworetzky loved his first go-round as a lawyer. From that very first week of law school, he found the work stimulating and challenging, and he was exceptionally good at it.

A Little Tickle

Dworetzky worked as an attorney for 35 years, specializing in insolvency and enjoying the kind of illustrious career that likely raised some eyebrows when he eventually rearranged his resume to put journalism experience at the top. But the itch to write was always present: a little tickle just under the surface that Dworetzky was able to scratch by representing authors and other artists pro bono, serving as a reader for a novelist friend, and continuing to dabble in fiction writing during his free time.

“I still wasn’t really finishing things,” Dworetzky remembers. “I was getting them started and thinking big thoughts about them but wasn’t really doing the hard work of making them come together.”

Then, one day, Dworetzky did something different. He finished a story.

“Everything changed when, instead of just a fragment of something, I had a complete story and then another and another,” he says. “And I didn’t do anything with them. I didn’t send them out to be published and didn’t really even show many of them to people, but it changed how I felt about my ability to tell a story.”

Soon, stories were filling up a three-ring binder, and Dworetzky had an even bigger idea. By then, he had four children. He wanted to write a book that would allow him to speak to them—to say things he knew they couldn’t really process if the words were coming out of their father’s mouth in real time.

He started waking up at five in the morning to write until seven, when the routines and obligations of the day could no longer proceed without his attention. It took more than a year of drafting and even longer to edit, but finally, Dworetzky had a published young adult novel he was proud of.

Kirkus Reviews reviewed Nine Digits, which Dworetzky wrote under a nom de plume. “A quote on the novel’s back cover compares it to Norton Juster’s 1961 classic The Phantom Tollbooth, and … Duret’s book really does begin to approach the witty, imaginative, and accessible brilliance of that genre-busting work.” The book’s success coincided with a major life change for Dworetzky, whose wife was offered an exciting professional opportunity in the San Francisco Bay Area. The couple and their two younger children moved across the country to start over on a new coast.

Dworetzky allowed the fresh start to extend beyond his geography. He agreed to stay on with his law firm to continue ongoing work but carved out most of his days for writing. For the first time in his life, he was free to write full time—and he wanted to.

Starting Over

He began sending his writing out, navigating a brand-new world of solo creative work in San Francisco. At nearly 60 years old, he was starting over.

“I didn’t really have many friends out here. I didn’t know anybody,” Dworetzky says. “So, it was like really starting at the very bottom of the ladder. A new discipline, a new city. No structured support.”

The social capital he’d built as a lawyer in Philadelphia, where he had a large network of friends and acquaintances to call upon for various things—support, validation, distraction—was replaced by an unencumbered sense of freedom but also with a sense of aloneness and a large measure of rejection. Instead of feeling secure and confident each morning, hardly having to think about how to get things done, Dworetzky now felt unsure. He got up every day, went to his desk, and tried to figure out how to tell a story in a way that would interest other people and satisfy himself.

“You’re in your head a lot,” he says. “You’re solving issues that nobody else knows about. They don’t make any sense to anybody. And so, you’re really just doing it yourself, and that isolation I thought was challenging.”

But instead of letting the uncertainty best him, Dworetzky began joining writers’ groups and seeking out the company and counsel of other authors. With all the diligence and determination with which he had thrown himself into the study and practice of law, Dworetzky embarked on a serious quest to become a professional writer.

For Dworetzky, writing was not a side hustle or a pastime. “I’ve always been terrified that people would think of my writing as a hobby,” he says. “I’ve always had very ambitious ideas for what I could do as a writer.” He told himself, if he was actually going to make a career switch at an age when many of his compatriots were wrapping up their professional pursuits, he had to go all in.

At the same time, Dworetzky was letting himself have fun with a far less staid pursuit. In working with an illustrator for Nine Digits, he had struggled to communicate the exact look and feel of the drawings to accompany the text. He started playing around with illustrating his own short stories. To enforce a bit of discipline, he committed to completing a drawing and posting it on his website every day.

Dworetzky says that at first, his drawings were not that good. “In fact, they were so bad that I started putting a little line of text into the drawing, almost like a T-shirt kind of slogan, which I thought would distract a little bit from how bad the drawing was,” he says. “I had probably been doing it for three or four months before it occurred to me: Hey, this is a cartoon.”

His cartoons weren’t nearly as bad as he thought. An editor at SF Weekly, an indie print newspaper in San Francisco, took interest in them, and soon Dworetzky was supplying three cartoons a week for publication.

Armed with Ambition

He got more serious about the medium as he moved into political cartooning, and later he was accepted as a fellow at Stanford University’s Distinguished Careers Institute, a non-degree-conferring experience for highly accomplished mid-life professionals who want to deepen their knowledge in a field or expose themselves to a new one.

At Stanford, Dworetzky found the community he’d been craving. The narrative and sports writing courses he took also opened his eyes to the possibility of combining his interests in writing and cartooning with his experience as a lawyer and with the arts. A career as a journalist seemed to hit a sweet spot.

After finishing the program, Dworetzky felt he had only scratched the surface of the training he’d need to be a working journalist. So, at 68 years old, he got an internship.

Dworetzky started learning to write like a journalist as an intern on the Los Angeles Times’ Metro desk. For one assignment, he shadowed a wildlife ecologist with the National Park Service who was evaluating the health of red-legged frog populations following a devastating wildfire.

“We hiked around and talked for a long time,” says Dworetzky. “That story ended up running on the front page, which seemed to me like the greatest thing in the world. Here I am talking to people, and they’re talking to me, which is great fun, and then I’m trying to translate this into a narrative that would be interesting to other people. And now look: All these people are seeing this story.”

On the side of that burned canyon with his notebook, Dworetzky felt it. He was right where he was supposed to be: “It just seemed to me that this is the greatest thing ever. And I’ve had that feeling pretty much throughout the journalism I’ve done.”

In the fall, Dworetzky walked into another classroom with a bunch of twentysomethings. He was a new master’s student at Stanford’s journalism school.

Plenty of his classmates were more than a decade younger than Dworetzky’s first two children; he was three times as old as the youngest person in his graduate school class and twice as old as the oldest. But Dworetzky was pleasantly surprised to find that the kids in his program were as interested in getting to know him as he was in building relationships with them, and they shared a drive and a passion. “I found a bunch of people who just want to be friends,” he says. “And that really was amazing to me and great fun.”

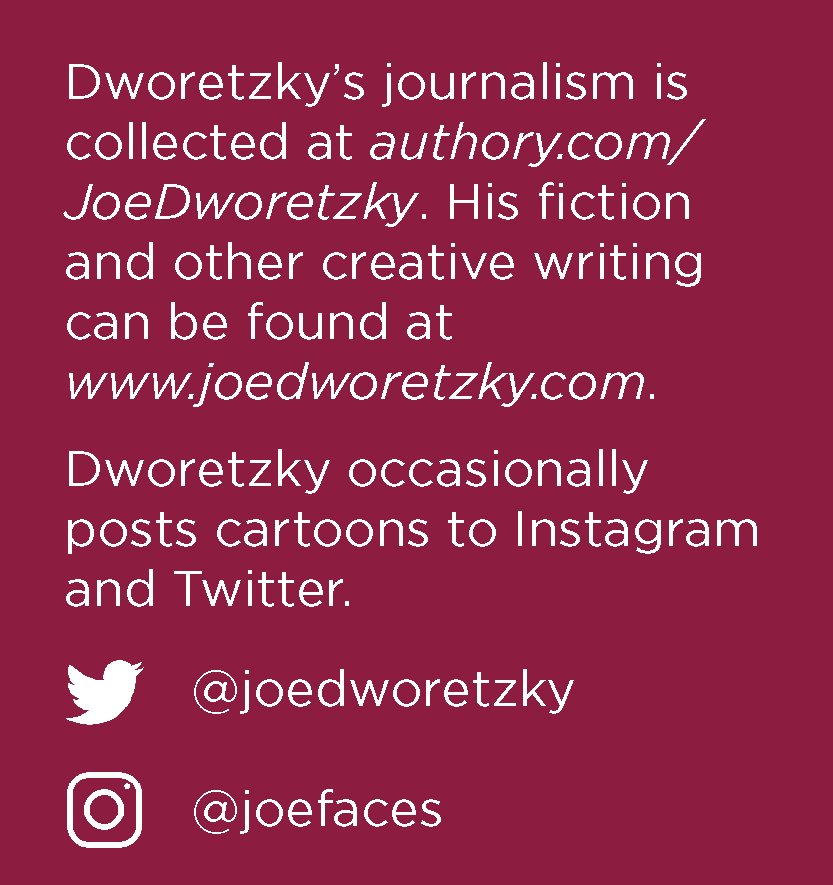

Out of 300 Distinguished Careers Institute alumni, Dworetzky is the only one to go on to earn a master’s degree from Stanford. He wrote and cartooned for the Stanford Daily, and after graduating, Dworetzky got an internship at Local News Matters, a community nonprofit newsroom that provides local news focused on the Bay Area to regional newswires reaching up to 8 million readers. He was soon offered a full-time position reporting on legal affairs, arts, and culture. He continues to post social and political cartoons to its website, Bay City Sketchbook.

Doing Work That Matters

“It is a bit of a surprise to me to be working full time,” he says. “I’m now 70. And I make this joke all the time, but I do believe I’m the oldest cub reporter in the United States.” Despite the deadlines and the demands of being an early-career journalist, Dworetzky doesn’t miss the lawyer life. He’s doing work that matters—not just to his clients but to himself.

Dworetzky finally tells people that he is a writer. “I didn’t do that until pretty recently,” he says. “But I do think of myself that way. And that’s a change.” He’s relishing the opportunities to keep learning and exploring. And he has no intention of sitting down and looking back just yet. “I have a long ways to go,” Dworetzky says. “I have ambitious ideas about the work I’ll do.”