A Quarter with More Questions than Answers

Rising inflation, the specter of higher interest rates, and the outbreak of war made for a challenging backdrop for investors during the first quarter.

The year began with modest declines across major asset classes in a synchronized sell-off as investors processed a range of significant global crosscurrents. Only commodities moved higher during the quarter, accelerated by supply shocks stemming from the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Normally sedate bond markets were rattled by inflation fears and the beginning of a Federal Reserve tightening campaign.

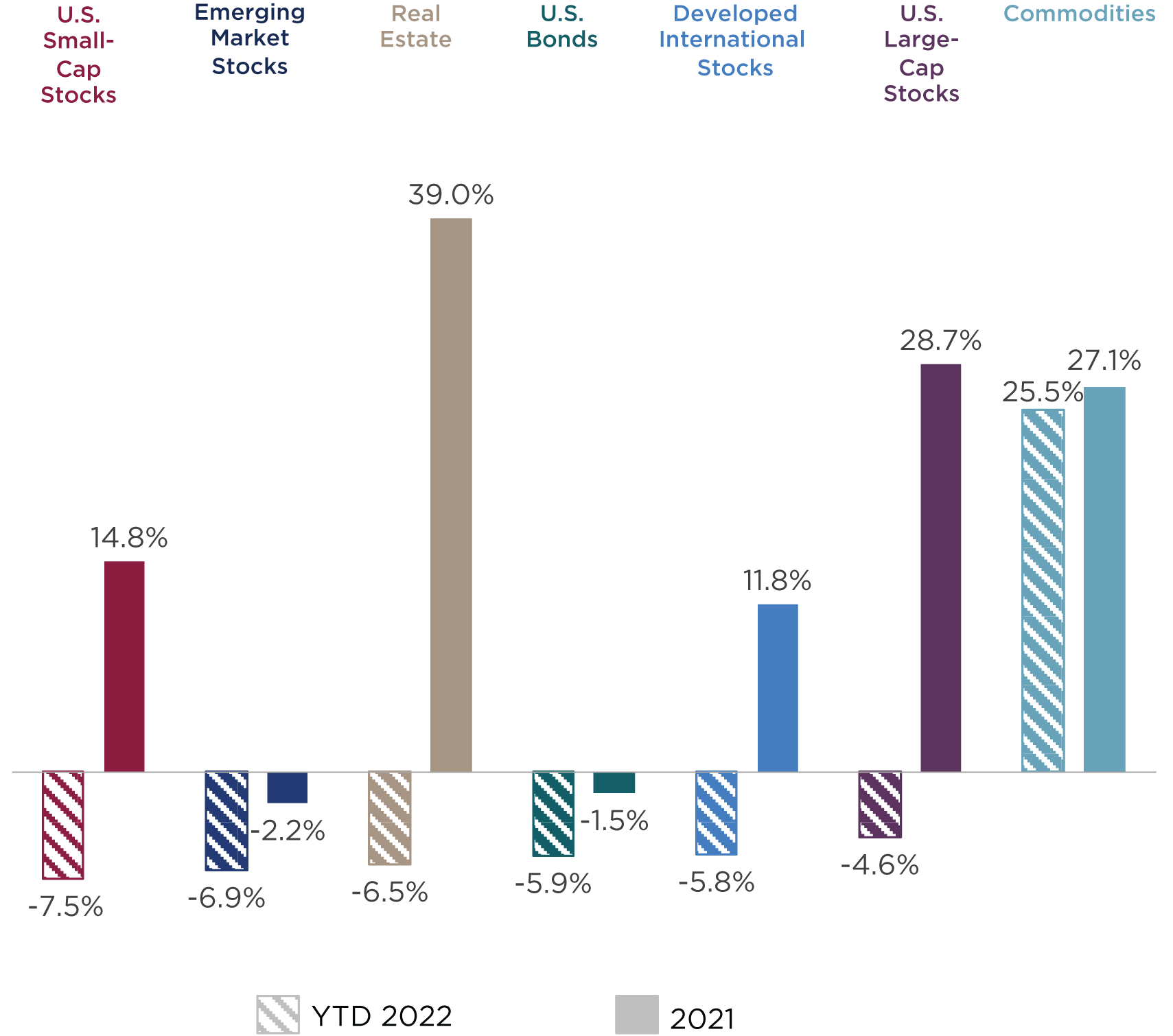

Figure One: Major Asset Class Returns

Source: Bloomberg. Asset class returns are represented by the following indexes: Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index (U.S. bonds), S&P 500 Index (U.S. large-cap stocks), Russell 2000® (U.S. small-cap stocks), MSCI EAFE Index (international developed market stocks), MSCI Emerging Market Index (emerging market stocks), Dow Jones U.S. Real Estate Index (real estate), and Bloomberg Commodity Index (commodities).

- U.S. large-cap stocks declined 4.6 percent during the first quarter despite a strong March rally, as the S&P 500 delivered its first quarterly decline since the first quarter of 2020.

- International stocks fared worse amid fears of energy and commodities shortages. Developed market stocks slipped by 5.8 percent, while emerging markets stocks dropped by 6.9 percent.

- Bond prices retreated as interest rates rose, leading to a 5.9 percent decline in the first quarter, the largest quarterly loss for the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index in more than 40 years.

- The only major category to post gains during the quarter was commodities, as prices for a wide range of inputs—from food to energy and basic materials—surged higher amid higher demand, constrained supply, and the shock of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The result was the best quarter for commodities since 1990.

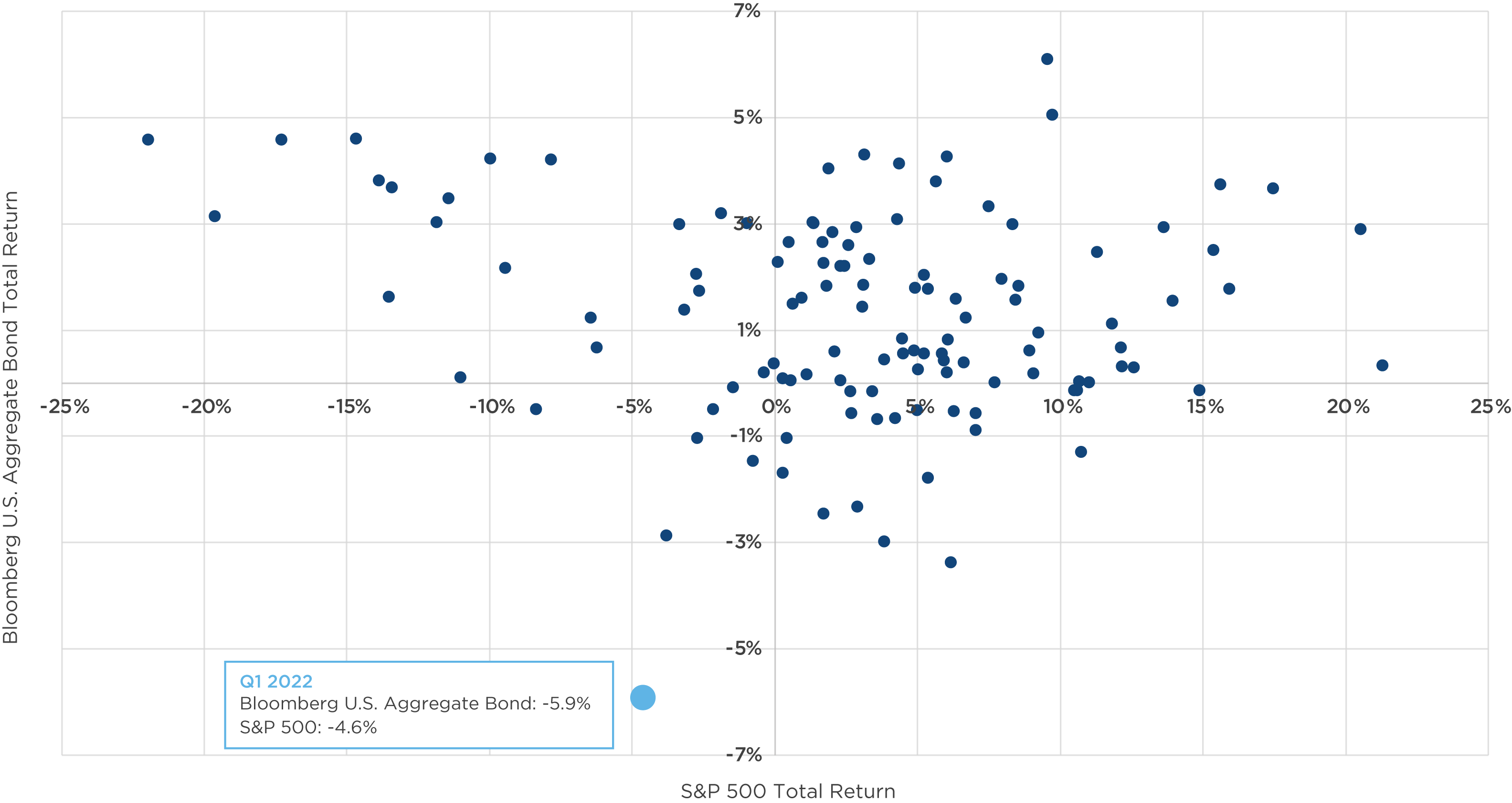

The first quarter was a rare instance when diversification felt more like diversi–frustration, as both the S&P 500 and the Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond indexes suffered simultaneous declines, something that has occurred in just six other calendar quarters over the past 30 years. As shown in Figure Two, when stock prices fall, bonds typically appreciate, providing a counterweight and diversification benefit (see top left quadrant). But during the first quarter, bonds also fell sharply (lower left), leaving investors with few places to hide.

Figure Two: Quarterly Returns for U.S. Stocks and Core Bonds (since 1992)

Sources: Bloomberg, CAPTRUST Research

A World of Two Wars

We entered 2022 with the belief that, following the abnormal economic, market, and policy conditions arising from the COVID-19 pandemic, investors should brace for a return to more normal market conditions, including the higher levels of volatility and market pullbacks that characterize them. Even so, we were surprised by just how quickly volatility returned, beginning the very first week of the year. Even as businesses and consumers continued to recover from the economic consequences of the pandemic, the outbreak of two simultaneous wars introduced new risks and uncertainties: the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the Federal Reserve’s war on inflation.

Unfortunately, the first of these wars is measured in human lives and destroyed cities. The invasion of Ukraine is both a humanitarian nightmare and a conflict that poses significant economic risks to the global economy. And while the second war pales in comparison on a human scale, the consequences of elevated inflation and the policy actions needed to bring it under control have pushed both interest rates and market volatility sharply higher.

Rising Prices Raise Alarms

Even before Russia invaded Ukraine, the U.S. economy was facing levels of inflation not seen since the 1980s due to pandemic-driven supply and demand imbalances and the extraordinary government stimulus used to blunt the economic damage caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

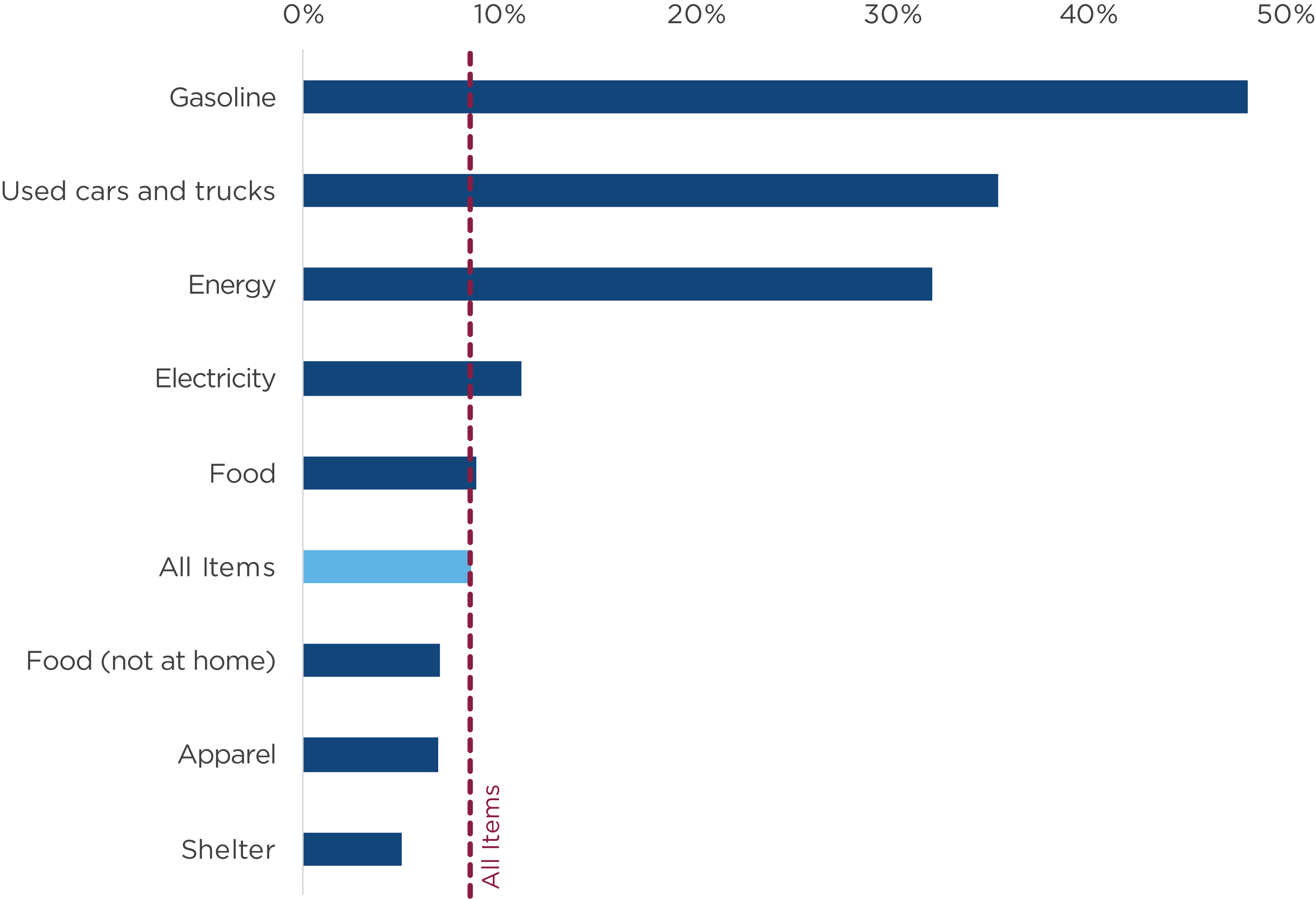

After climbing steadily in 2021, inflation accelerated this year, with the Consumer Price Index (CPI) touching 7.5 percent in January on its way to a whopping 8.5 percent year-over-year increase in March—the highest reading since 1981. With this level of inflation, it’s no surprise that consumer sentiment has fallen to one of its lowest points in the past 70 years, as rising costs have significantly eroded the benefits of wage gains for many workers.

However, hidden within the March inflation data were some glimmers of hope that the trajectory of inflation could flatten or even decline later this year. Over half of the March increase was driven by an 18 percent spike in gasoline prices within a single month due to the Russian invasion. Oil prices have since moderated from weaker demand due to China’s severe COVID-19 lockdowns and the impact of the largest-ever releases of oil from strategic petroleum reserves.

Other bright spots in the March CPI data: Core price inflation, which excludes the volatile categories of food and energy, rose by a smaller amount, and used car prices posted a significant monthly decline. Vehicle prices are still elevated over pre-pandemic levels and could serve as a continuing source of disinflation as the automobile market normalizes.

An Inflation-Fighting Fed

Figure Three: Consumer Price Index Year-over-Year Change (March 2022)

During the pandemic, as factories were shuttered and supply chains were jammed, massive stimulus payments and lower costs gave people money to spend. This is a clear recipe for higher prices, and the hope was that inflation would fade as pandemic disruptions began to resolve. But as we entered the new year with inflation signals flashing red and the strongest labor market in a half century, the Fed was forced to use its words—also known as Fedspeak and closely scrutinized by analysts—and its policy actions to reduce the inflation threat.

The only way to tamp down inflation is to slow the pace of growth within an economy that’s running full tilt, and the Fed has several tools to do so. The first is raising the federal funds rate, the interest rate that is used for short-term loans between banks. The fed funds rate flows through the financial system into all kinds of business and consumer credit. Higher rates increase borrowing costs, reduce consumer demand and business investment, curtail more speculative activity, and cause the economy to cool.

In mid-March, the Federal Reserve hiked the fed funds rate by 0.25 percent. This represents its first uptick since 2018 and the opening salvo of an inflation-fighting campaign expected to deliver seven or more rate hikes this year. But the minutes of the Fed meeting released several weeks later supply even stronger indications that more aggressive 0.50 percent increases are also on the table. Investors have taken these comments to heart, with the futures markets suggesting a nearly 87 percent probability of a 0.50 percent increase during the Fed’s next meeting in May, according to the CME Group’s FedWatch Tool.

The March meeting minutes also yielded clues about another weapon within the Fed’s inflation-fighting arsenal: quantitative tightening—or reducing the size of its enormous balance sheet of securities purchased during the crisis to inject liquidity into the financial system and keep borrowing costs low. The March minutes suggest that the Fed could begin quantitative tightening as early as May at a pace of up to $95 billion per month.

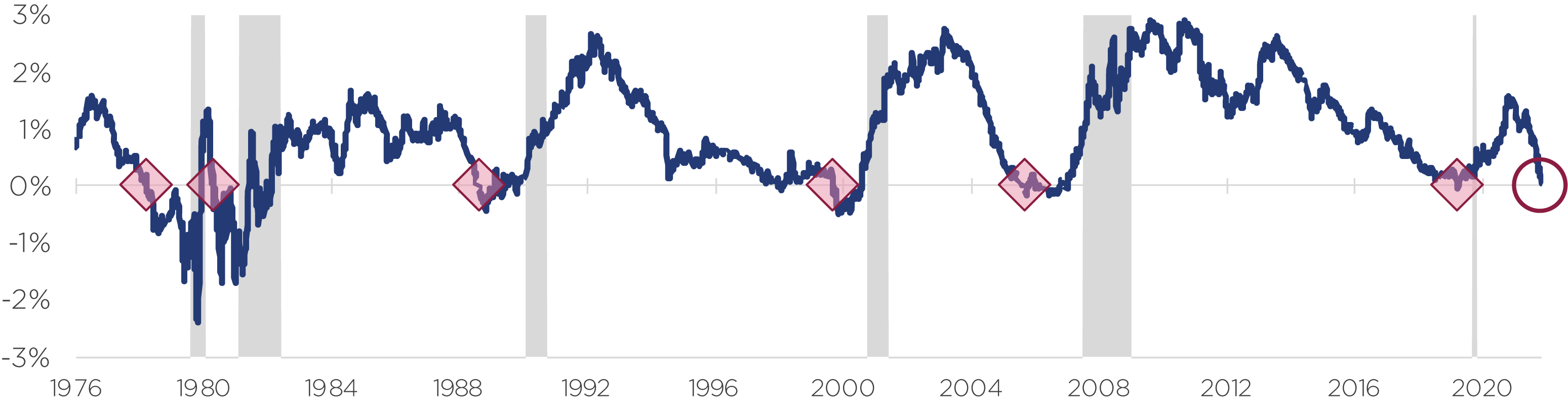

Bond markets have reacted swiftly to the Fed’s hawkish pivot. Two-year Treasury yields, which are more sensitive to the fed funds rate, leapt from 0.7 percent to 2.3 percent over the course of the first quarter. This rapid rise in short-term yields led to the market condition known as an inverted yield curve, where yields for long-term bonds fall below those of shorter-term bonds. Historically, this condition has been a reliable harbinger of recession.

Figure Four: Spread between 10- and 2-Year Treasury Yields

Sources: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Strategas, CAPTRUST Research

Although the yield curve inversion at quarter-end was brief, it highlights one of the biggest questions facing investors today: Can the Fed can prove the yield curve wrong by employing its policy tools to engineer an economic soft landing that reduces market excesses and inflation without pushing the economy into recession? This is a hard enough task in a normal market cycle but is greatly complicated by the war in Ukraine, the experimental nature of quantitative tightening, and the lingering effects of a global pandemic.

Economic Impact of War in Ukraine

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine represents, first and foremost, a shocking humanitarian crisis and a threat to global peace and stability. It has also introduced an unpredictable factor to global inflation dynamics, as the production and distribution of key commodities have been interrupted by both the conflict and the financial sanctions imposed to punish Russia’s aggression.

Russia is a major exporter of key industrial and food commodities. It is the second-largest net exporter of crude oil, the fourth-largest provider of natural gas to global markets (which supply much of Europe’s electricity), and the top exporter of fertilizers that are critical to global food production. Perhaps most critically, together Russia and Ukraine export almost 30 percent of the global trade in wheat, as well as other important grains and vegetable oils used in food production, according to the Observatory of Economic Complexity.

In the days following the invasion, prices spiked for a range of energy sources, industrial metals, and food staples. This could amplify inflation pressures in the months ahead and create risks of global food shortages that could trigger political or social unrest. In March, a global food price benchmark compiled by the United Nations rose by nearly 13 percent, reaching the highest level since the index was created in 19901.

What Could Go Right?

During a volatile, breaking-news-driven market environment, it is also important to consider what could go right from here. Fundamentals remain in place for investment gains if the trio of macroeconomic risks—inflation, the Fed’s actions to contain it, and the war in Ukraine—can be better understood by investors.

Despite a backdrop of rising uncertainty, U.S. stocks suffered only modest declines during the first quarter, in part because economic and business fundamentals remain strong. Although U.S. companies’ profit growth has slowed due to rising input and labor costs, margins still are well above their long-term averages. Meanwhile, investors have cheered as companies continue to return capital to shareholders.

Companies have two primary ways to return capital to investors: dividends, which are more certain but immediately taxed, and stock buybacks, which can defer taxation but provide a more uncertain future return. Last quarter, buybacks set a record at $270 billion—more than double the pace of the same period in 2020. Companies also set a record for dividends in 2021, returning more than $500 billion to shareholders, according to data service Bloomberg.

And despite rising input and labor costs, high levels of profitability continue to serve as a tailwind for stocks, as strong consumer demand and productivity gains have allowed firms to pass higher input and labor costs along to customers.

More Questions than Answers

Amid this challenging backdrop, investors are hungry for clarity. Based upon our ongoing conversations with clients, asset managers, and other market participants, we believe that some of the most important questions investors face today fall into four categories.

The Russia and Ukraine War

- How extensive will the human, physical, and financial damage from the war in Ukraine be?

- How long will the conflict last, and will it tip Europe into recession?

- How will the conflict impact energy, industrial, and food commodity prices?

Inflation and the Fed

- Are we nearing the point of peak inflation?

- Can an inflation-fighting Fed avoid a policy error and engineer an economic soft landing?

Business Conditions

- Will oil prices rise further and remain higher for longer?

- When will worker shortages resolve?

- Will higher wages and inflation draw workers from the sidelines?

- When will the effects of rising prices offset higher wages and elevated levels of savings, dampen consumer demand, and reduce the ability of companies to maintain profit margins?

The COVID-19 Pandemic

- Will COVID-19 and its economic impacts remain in the background?

- When will global supply chains catch a break?

Given this list of questions, our view remains cautious. However, this doesn’t mean investors should head for the exits to wait for an all-clear. In fact, some of the best days in the markets have historically come during the depths of a crisis, when the all-clear isn’t yet obvious. During volatile markets, investors’ greatest assets are caution and patience, and it is far better to remain invested with a diversified portfolio that is resilient to a wide range of conditions.

1Alistair MacDonald and Patrick Thomas, “Ukraine War Drives Food Prices to Record High,” Wall Street Journal, April 8, 2022