Connections Across Generations

Research suggests Reeg is on to something. Older adults who build meaningful bonds with younger people, whether in their families, workplaces, or communities, live longer and happier lives. In fact, one long-running Harvard study recently found that social connection is the strongest predictor of well-being as we age. Bonds with younger people are particularly powerful happiness boosters, the research shows.

“Connection of any kind counters loneliness, which is especially common among youth and older adults,” says Kasley Killam, founder and executive director of the nonprofit Social Health Labs. Loneliness in older adults is linked with dementia, heart disease, and premature death, according to the National Institute on Aging.

Connecting with younger people is “a chance to be in touch with where the world is going” and to feel a greater sense of purpose in that world, says Katharine Esty, an 88-year-old psychologist and author of the book Eightysomethings. But to bridge the gaps, it helps to understand more about who is on the other side.

Beyond Bashing

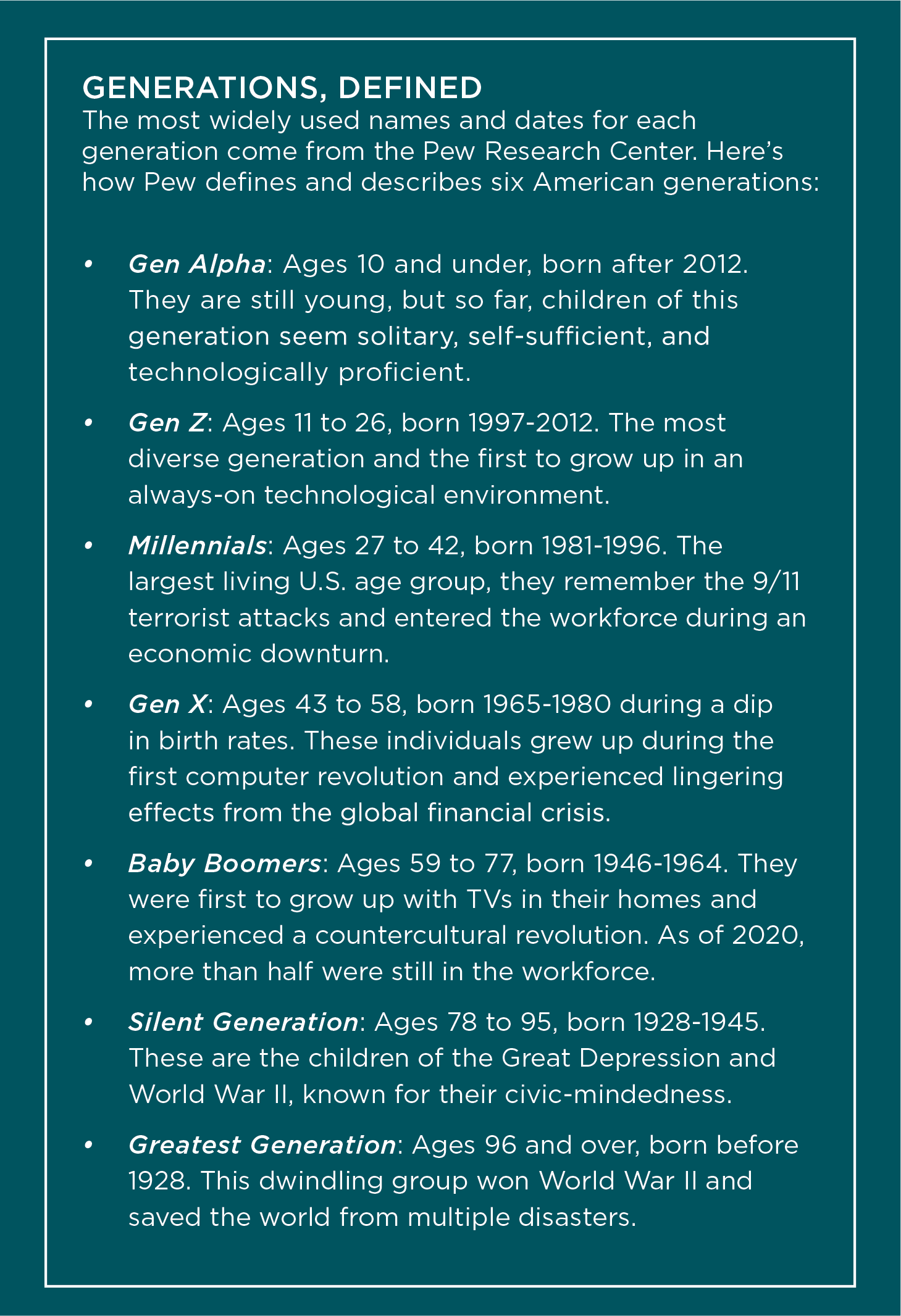

Baby boomers were once viewed as being too revolutionary. Gen Xers were slackers. Millennials were entitled. And today’s young adults, members of Gen Z, are often branded as overly sensitive snowflakes, writes Megan Gerhardt and her colleagues in their recent book Gentelligence: The Revolutionary Approach to Leading an Intergenerational Workforce.

A few years ago, Gen Zers hit back with the “OK, boomer” retort to dismiss “older people who just don’t get it,” The New York Times reported. Gerhardt, also a Miami University business professor, says this type of generation bashing is downright unproductive, pushing people farther apart instead of helping them find a middle ground.

But understanding how each generation is different and unique can help people build stronger social ties, says Roberta Katz, a senior research scholar at Stanford University and co-author of Gen Z, Explained: The Art of Living in a Digital Age. The book is based on interviews, surveys, focus groups, and social media posts from teens and young adults born after the mid-1990s.

The young people who Katz and her colleagues spoke with when writing the book pushed back on the idea that they are fragile, coddled, and unable to deal with the world beyond their phones, she says.

Everyone who is alive today is experiencing the same technological and social upheaval, says Katz. “The difference is that’s the only world Gen Z knows. And we don’t know what the world looks like from their vantage point. We assume we do because we were young once, but we don’t really know.”

People born into Gen Z—that is, between 1997 and 2012—are “burdened by what feel like existential threats to their future,” such as climate change and school shootings, Katz says. They are wary of authority and hierarchy, something their schools and employers are grappling with. But, she says, they are eager to work collaboratively to solve the world’s problems.

They also are less glum than generally thought, says Sophia Pink, a 26-year-old doctoral student at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business. As an undergraduate at Stanford, Pink spent a summer interviewing fellow 21-year-olds around the country and learned that “they were pretty optimistic about their own lives and their own plans,” even as they despaired for the wider world.

It is true, Katz says, that younger people spend a lot of time on their phones. They can be impatient when older people don’t understand or follow their digital ways—for example, when their parents or grandparents send emails and leave voicemails although a simple text would do. But, she says, they do crave meaningful connections with others, including older people in their lives.

Reeg says she’s learned exactly that by spending time with her grandchildren. “If I have one of my grandkids in the car with me, and they’re looking at their phone while I’m talking, I just want to scream, take the phone, and throw it out the window. But I’ve learned that they can multitask better than we ever could. And actually, they are listening.”

There’s some truth to the idea that younger and older people “live in different worlds” and “speak different languages,” says Esty. Misunderstandings and hurt feelings can go both ways, she says. “Older people can feel ignored and not taken seriously,” just as younger people can.

But overcoming these barriers is worth it.

Photo above: Christeen Reeg and her grandchildren

“Older adults have wisdom and experience,” Killam says. “The younger generation brings a fresh perspective.” And connecting across generational divides can bring a greater sense of happiness and purpose for people of all generations.

Jumping the Chasm

Sometimes, bridging generational gaps can be particularly challenging. For example, consider a family in which grandparents and young adults have become estranged from each other for any number of reasons. In these cases, it’s important to remember that big emotions tend to fade over time and that past hurts can be easier to resolve than most people expect.

The more common problem, Esty says, is that “people don’t make the effort.” Since the first steps are usually the hardest, it helps to make them small.

That might mean doing what many older people did for the first time during the pandemic: using Zoom and FaceTime to meet up virtually with family, friends, and colleagues. People were craving human connections and leaping over technological divides to make them, social scientists say.

Older adults who now play online video games, use apps to watch movies with faraway friends, or swap daily Wordle scores with their children and grandchildren have made similar leaps. So have those who’ve become avid texters—even if they do use more punctuation and fewer emojis than their younger contacts would prefer.

Reeg says she tries to text each of her grandchildren at least once a week. “I’ll go through pictures, and I’ll see a memory picture, and I’ll just send it and say, ‘Thinking of you.’”

But older adults should not feel obligated to use digital technologies they don’t like. “Be true to yourself, and if you hate it, then don’t do it,” Esty says.

Pink says younger adults do understand that not everyone wants to use text or video chat. That’s why she calls her own grandparents on their landline.

Likewise, older workers don’t have to adopt all the technological tricks and habits of their younger colleagues, says Marci Alboher, a vice president at CoGenerate, a group that focuses on bringing multiple generations together to do good work. But, she says, everyone benefits when they can share favorite tools, like Zoom, Google Meet, or WhatsApp.

Beyond Tech Tools

Alboher says it’s wrong to assume that all younger people prefer texts and instant messages or that all older people prefer emails and phone calls. It’s better, she says, to ask. “If you are starting to work with someone or you’re joining a team, you can have a conversation about norms and preferences. You may expose yourself to some new communication styles, and you may find that people are suddenly more responsive to you.”

But don’t discount the value of a good in-person conversation. Katz says, in her research, one revelation was that young people valued in-person interactions above all others. “They are very much about human connection,” she says. “They want to be seen, and they want to be heard, just like everyone else.”

When you have those conversations, she says, be sure to listen, not just talk. “Don’t be judgmental. Ask them about their lives.”

Sometimes, connecting with younger people means “stepping out of your own comfort zone” and getting past the way they are “dressed or groomed or adorned,” says Lauren Lambert, a CAPTRUST financial advisor based in Boston, Massachusetts, who has advised multigenerational households, mentored younger colleagues, and raised two millennial children. “It’s important to respect them and their struggles. You really have to listen to them and remember what it was like to be their age.”