Fourth Quarter Investment Strategy | An Economy That Refuses to Land

The term soft landing has pervaded economic commentaries for years. A soft landing was the optimistic outlook for the U.S. economy in late 2023 and the consensus prediction for most of 2024. But as 2025 begins, economists have started asking whether the economy will ever really land.

Two years ago, many market watchers thought they knew what would happen next. An extra $4.6 trillion, more than 15 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), had been injected into the economy since the beginning of the pandemic. Traditional economic theory assumed this gigantic stimulus would cause the economy to overheat, leading to an economic correction. Maybe, if everything went right, it could avoid a hard landing (a recession), but it would still have to face at least a soft one. In this soft-landing scenario, the economy would bump along for a while at low, but above zero, levels of growth before reaccelerating.

Yet, so far, there have been no dire repercussions—no big drop in consumer spending, no significant increase in unemployment, and no outbreak of housing foreclosures or business bankruptcies. The economy has cooled in an orderly fashion as economic distortions caused by the pandemic have slowly subsided. The consensus outlook for the U.S. economy has morphed from recession imminent to soft landing and now to no landing.

Fourth-Quarter Recap: The Rally Broadens

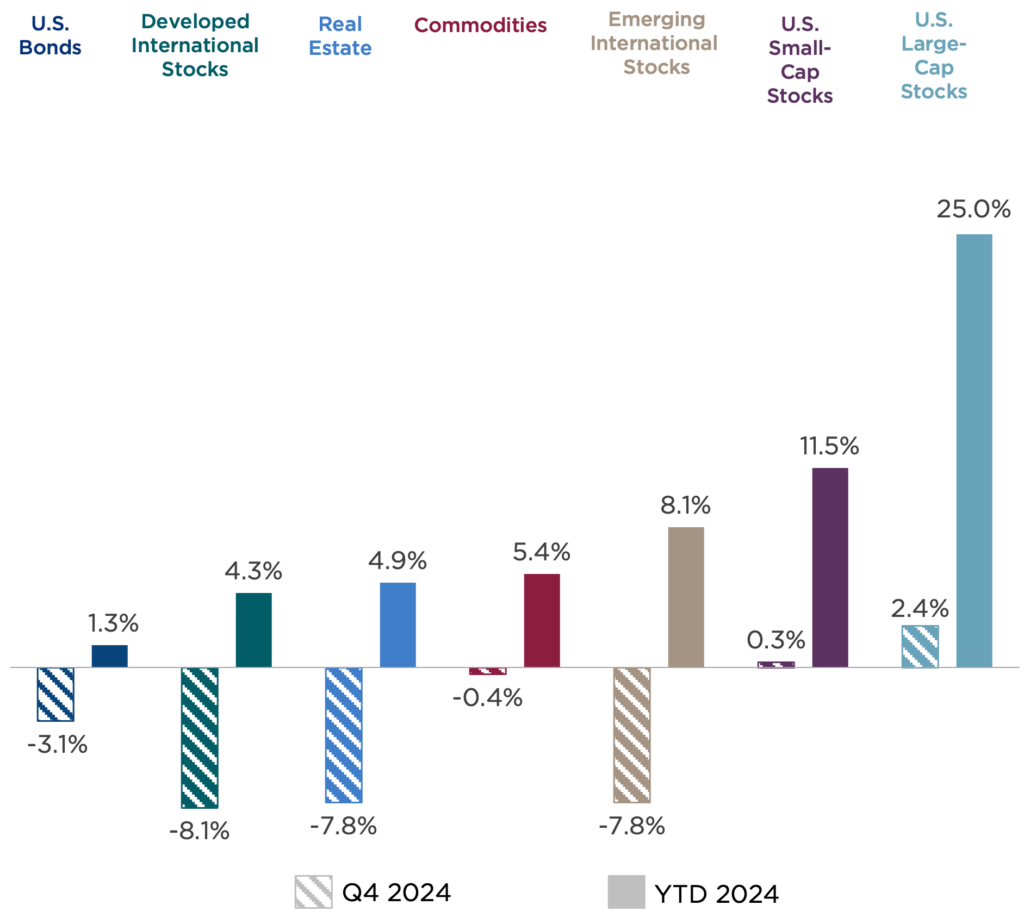

The fourth quarter of 2024 was marked by a stronger U.S. dollar and rising long-term fixed income yields. These shifts reflect both a resilient economy and worries that the new administration’s policies could be inflationary. Against this backdrop, most asset classes slumped.

In the U.S., large-cap stocks were the exception, climbing not only for the quarter but also for the last two years, with gains of 25 percent or more in both periods. This cohort has shown strong earnings performance and stands to gain significantly from the rollout of artificial intelligence (AI) technology.

A strong dollar and rising interest rates tend not to be favorable for international stocks, fixed income, real estate, or commodities. All these asset classes declined in the fourth quarter and lagged for the full year.

Figure One: Q4 2024 Market Rewind

Asset class returns are represented by the following indexes: Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index (U.S. bonds), S&P 500 Index (U.S. large-cap stocks), Russell 2000® (U.S. small-cap stocks), MSCI EAFE Index (international developed market stocks), MSCI Emerging Market Index (emerging market stocks), Dow Jones U.S. Real Estate Index (real estate), and Bloomberg Commodity Index (commodities).

Interest Rate (In)Sensitivity

When battling inflation, the Federal Reserve’s primary tool is to increase interest rates. Higher rates make borrowing more expensive and, in turn, tend to stifle demand throughout the economy. Most Fed hiking cycles have led to recessions. Indeed, at the beginning of the most recent hiking cycle, Fed Chair Jerome Powell warned of this possibility, saying the battle against inflation could be “painful.”

But this time has been different. Ultra-low interest rates during most of the 2010s allowed some borrowers to lock in low rates for long periods, insulating themselves from the higher rates that came later.

Many who didn’t lock in low rates are now struggling to afford the larger purchases, like homes and vehicles, that help drive economic activity. Housing supply has been constrained, since current homeowners don’t want to give up their current low mortgage rates, and reduced supply has increased home prices across the country. This doesn’t usually happen when rates are rising.

The Search for Neutral

In September, the Fed started cutting interest rates, even though inflation had not reached its 2 percent target. This indicated a shift in monetary policy. In Powell’s words, “Recalibration of our policy stance will help maintain the strength of the economy and the labor market and will continue to enable further progress on inflation as we begin the process of moving toward a more neutral stance.” The Fed is trying to find a neutral policy.

Neutral policy is the level of the fed funds rate called R*. This is a theoretical rate that neither stimulates nor restricts the economy. All else equal, it is where the Fed would prefer to set policy. It is theoretical because there is no way to calculate the precise level of R*. It can change based on myriad conditions affecting the economy.

Since the first rate cut in September, the Fed has cut the fed funds rate by a total of 1 percent, ending 2024 at 4.25-4.50 percent. In its December 2024 “Summary of Economic Projections,” the Fed presented a median long-term forecast for the fed funds rate of 3.00 percent. But that’s a level it doesn’t expect to achieve until after 2027.

Part of a normal interest rate environment is that longer dated interest rates should be higher than shorter dated ones. This is known as a positively sloped yield curve. In the past few months, the yield curve has regained a positive slope. Before then, you may have heard it was inverted. The change to positive sloping might indicate a normalizing economy, but it could also reflect other factors, such as concerns related to government debt or higher long-term inflation expectations.

How and when the fed funds rate and the yield curve finally normalize have enormous implications for the economy and for asset prices. Higher yields on fixed income investments, such as bonds, may make the cost of capital too high to support economic growth. Fixed income investments and stock valuations tend to be inversely correlated. When one goes up, the other goes down. Fixed income levels deemed too high to support current stock valuations could result in a market correction.

Productivity Surge

The U.S. labor force is not growing very much. The latest count, from December 2024, was virtually unchanged from a year prior, and this includes the net effect of immigration. Yet despite this lack of labor growth, the economy has managed to grow by about 5 percent. This was achieved through the miracle of productivity.

Productivity is measured as GDP per hour of work. Getting more output per each unit of labor creates excess output that can be redirected into the economy in many ways, including wages and corporate profit growth.

Economic growth from productivity sets the U.S. apart from its developed market counterparts, where productivity has stagnated this century. It also provides much of the explanation for the outperformance of U.S. stocks during this period.

The largest companies in the world (many of which are based in the U.S.) are investing heavily in new technologies to accelerate productivity gains. These investments are likely already having a net-positive effect on the economy. If AI technology achieves even half of what its supporters are promising, the U.S. economy could be entering a golden age of productivity.

Conflicting Signals from Corporate Earnings

Among publicly traded companies, there have always been the haves and have nots, but the differences have rarely been so stark as they are today. Large companies are enjoying heady growth and productivity gains. Those with large cash piles and minimal debt have also managed to benefit from higher interest rates. In 2024, earnings per share for the S&P 500 Index grew by about 10 percent and are expected to grow another 15 percent in 2025.

By contrast, smaller companies have floundered. This cohort is far more heavily impacted by higher interest rates and regulatory burdens, and the primary index on which they trade—the Russell 2000—saw 2024 earnings roughly equal to 2018.

Such a top-heavy distribution of economic gains can have negative side effects for the economy. Small businesses represent most of U.S. employment. Stagnant or declining earnings may result in significant layoffs or, worse, business closures across the country.

Government Debt

Another factor worth watching this year is the federal government’s debt. The torrent of pandemic-related stimulus from 2020 to 2022 added to an already stretched government debt load, and the burden is now getting harder to carry as higher interest rates make debt more costly to service. At present, the federal government pays more in interest payments for outstanding debt than it does for all its military operations.

How does government debt impact the economy? Debts and deficits of this magnitude threaten to crowd out private-sector businesses by making them compete with the government for lenders’ dollars. A local restaurant has a harder time borrowing when the government is paying nearly 5 percent interest. This level of debt also makes it more difficult for the government to spend on other, economy-boosting line items.

The quickest way to address the issue is through austerity—that is, reducing public expenditures—but this would have a direct negative impact on the economy. Another way is to increase the money supply in order to pay the debt, but this would likely hurt the economy indirectly by increasing inflation.

A better way is to outgrow it. A larger economy makes the current amount of debt smaller as a percentage and can bring in more tax dollars to reduce the deficit.

New Administration, New Policies

The policy promises from President Trump’s campaign, if enacted, have the potential to create major economic impacts. But promises can be difficult to fulfill, so we’ll have to wait and see which items become reality.

Deregulation is one of the most likely policy agendas to be implemented. Eliminating regulations tends to produce higher growth rates as businesses are more willing to risk productive capital when the regulatory environment is less burdensome.

Other suggested policy shifts could have mixed or even negative effects. Examples are tariffs, which could impact supply chains and the cost of goods; immigration, which could impact supplies and the cost of labor; taxes, which could impact corporate earnings and aggregate demand; and the Department of Government Efficiency, which could impact the level of government spending.

Clear Skies Ahead?

When describing the economy, market pundits often use airplane metaphors. The economy can be taking off, cruising along, landing, or facing turbulence.

Here’s where the metaphor falls apart. Although an airplane always needs to land, the economy doesn’t. Real GDP, which excludes inflation, has grown every year since the turn of the century, except in 2008 and 2009 (the great financial crisis) and 2020 (the pandemic).

Historically, the economy requires either structural instabilities or external shocks to trigger a recession. At present, we see none on the horizon.

Structurally, the economy seems resilient. Consumer and business confidence are improving, jobs are plentiful, wages are rising, and inflation has eased. The U.S. equity market has responded to this economic backdrop with strong performance.

By their very nature, shocks tend to be low-likelihood events or completely unforeseeable. Any number of shocks with economic consequences could emerge, particularly from the numerous geopolitical events percolating across many parts of the globe. But let’s not prepare the runway just yet. It’s possible we may avoid a landing altogether.