Apex Mayor Jacques Gilbert Shares His Path to Local Government

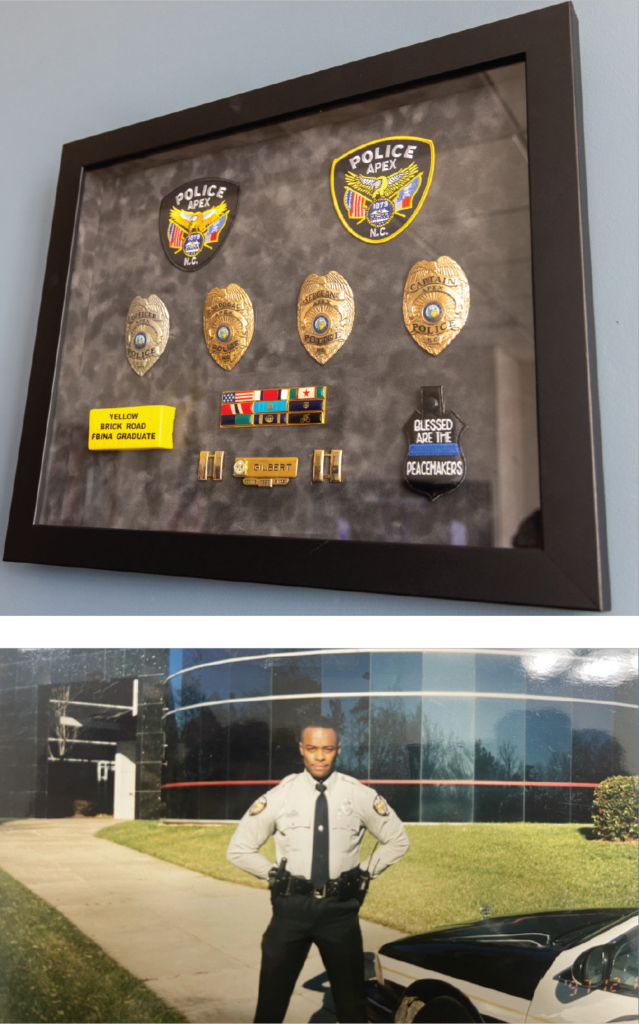

In 2019, Gilbert cleaned out his locker at the Apex, North Carolina, police department and officially retired from what he calls a highly unlikely 29-year career in law enforcement. Gilbert grew up in a culture where people distrusted and sometimes disliked police officers. Yet by all measures, he’d become a hugely successful one.

After a lifetime in the force, he put his uniform and badge away, turned off the lights, and walked out the door into charming, historic downtown Apex. “It’s been a great ride,” Gilbert wrote at the time. “On to my next assignment.”

This sign-off, he says, contained a hidden message. Gilbert was about to do something he once thought was even more unlikely than becoming a police officer. Seven months later, he was elected mayor.

Gilbert, now 54, grew up in Apex. His neighborhood, Justice Heights, was on the other side of what he says was a clear dividing line marked by State Highway 55. Most Black people lived on one side, he says, and people on the other side didn’t see the neighborhood or the people who lived there as part of their town.

Now, Apex is different—more diverse, more developed, and much larger. In 2023, the town’s total population was 77,000. In the 1970s, when Gilbert was a child, it hovered around 3,000.

Gilbert lived in public housing, where he witnessed repeated hardships in his community. He had friends and relatives who got in trouble with the police. Although he never had any personal run-ins with law enforcement, he got the message that police officers were not to be trusted. He certainly never dreamed of becoming one.

When Gilbert graduated from high school in 1987, he went to work as a water meter reader for the nearby town of Cary. “It was just a job,” Gilbert says, and he wanted something that felt meaningful.

“A friend of mine became a police officer,” Gilbert says. “At first, I thought, that’s not for me. In the community where I was raised, being a police officer, that’s not what we do. It’s not who we are. But my friend kept sharing all the great things he was doing, and it just really intrigued me.”

Gilbert let his curiosity lead the way, enrolling in criminal justice courses at a community college and working his way through the North Carolina Coastal Plains Police Academy. After graduation, he says, “Everything just started opening up.”

In 1990, Gilbert joined the Apex Police Department, eventually becoming the town’s first Black police captain and later graduating from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) National Academy.

Suggesting Solutions

His path toward becoming an elected official began by responding to a noise complaint. A teenager was annoying neighbors by doing skateboarding flips in his driveway. Gilbert found the teen, whom he recognized as part of a local skateboarding group that often got in trouble around town.

He told the young man, Tracy Stallworth, that he would have to stop. “He looked at me and said, ‘I can’t skateboard in my own driveway?’ And I said, ‘Nope.’ So, he picked up his skateboard, walked in his house, and slammed the door.”

Gilbert drove a few blocks away before he realized he had missed an opportunity. “I hadn’t offered him any solution,” he says. Gilbert was troubled by what felt like an unfair outcome.

So he rekindled the conversation with Stallworth, and they started dreaming of solutions. Their biggest idea was a downtown park where skateboarders could practice and hold competitions or events without disturbing neighbors. But a skate park seemed impossible at first.

In the meantime, as police captain, Gilbert helped organize weekend skateboarding events for the community—a short-term solution that often drew more than a hundred skateboarders and spectators of all ages. Over time, momentum for a skate park grew. Stallworth’s skateboarding friends helped raise funds and community support.

Making it real meant asking the town council for a significant amount of money, Gilbert says. “One night, they all skated to a town council meeting, and we filled the council chamber,” he says. Three of the skateboarders spoke, showing their enthusiasm and the growing demand for a safe skateboarding space.

The council saw their vision and, at the next meeting, approved $750,000 in funding—a huge amount, especially for a relatively small town. The council asked Gilbert and the skateboarders to raise another $250,000. With the help of a local benefactor, they did it.

Since it opened in summer 2015, the Rodgers Family Skate Plaza—often called Trackside because of its location between two historic rail lines—has become one of the most popular gathering spots in Apex. For their efforts, Gilbert and Stallworth were invited to the White House, where they received a Champions of Change award from President Obama.

Stallworth, now 28, says he was awed by the energy and passion Gilbert gave to the project. “Jacques, who had never skated a day in his life, put almost a year into this thing,” he says, and in the process, inspired Stallworth to show up and be a leader himself. Stallworth now gives free skateboarding lessons to kids. He wants to pay forward what he learned from Gilbert.

The skate park project got Gilbert thinking too. “If a young police officer, just a shy kid from the ’90s, can end up at the White House, perhaps he can inspire others to show up where they’re not invited,” he says.

Why Not You?

In Gilbert’s mind, becoming an elected official was farfetched and improbable. Community leadership didn’t feel like it was open to people from his background, and he had little understanding of what those jobs entailed. But others saw his potential.

Nicole Dozier, a local health policy advocate, says she was attending regular town meetings back in 2013, when Gilbert and Stallworth were campaigning for the skate park. She was there the night the skateboarders filled the chamber, and she was impressed. Later, Dozier became a town council member and served eight years as Apex’s mayor pro tempore.

During her second campaign, she says, she heard Gilbert was approaching police force retirement and asked him if he might consider running for office. “I thought he could be really inspiring,” she says. “People liked him so much.” Gilbert’s first response was, “Absolutely not.”

He was already focused on another big project: the Blue Lights College, a post-high school program for young people considering police careers. Gilbert was also busy training new officers, coaching youth basketball, and teaching self-defense classes. He likes to stay busy and meet as many people as he can.

One of the people he met was Jennifer Kopras. At the time, Kopras was 46 and hoping to fulfill her lifelong dream of becoming a police officer. Now, she’s a Blue Lights College graduate and has been a part of the Apex police force for more than a year. She says meeting Gilbert was a big part of her journey.

“Jacques sees a spark in someone and ignites it,” Kopras says. “He saw something in me and helped me follow my dreams. He gave me a little more hope to push through.”

Dozier saw a similar spark in Gilbert and kept encouraging him to run for office. “At some point, he finally said, ‘OK, I’ll think about it,’” she says.

A few months later, Gilbert was watching Apex’s annual State of the Town address when he says he heard a voice in his head asking, “Why not you?”

He went home and talked to his wife Meshara; daughter Kalabria, now 27; and son Logan, now 21. They loved the idea. “My son said, ‘You’re already the mayor! You just don’t have the title yet.’” Kalabria, a public relations professional, signed on as his campaign manager. With his family behind him, Gilbert felt confident and capable.

Stallworth says he heard the news through the grapevine and was glad but not surprised. “It just made so much sense,” he says.

A Golden Year

Gilbert is now in his second term, after winning an unopposed election in November 2023. Since he was first elected in 2019, his list of wins includes writing the town’s first-ever 10-year strategic plan, negotiating tens of billions of dollars of deals with big and small businesses that are relocating to Apex, instituting diverse holidays and better benefits for town workers, and leading the town through the intense period of COVID-19 shutdowns and racial unrest that have defined the last few years.

Throughout, he has maintained his focus on providing solutions and building community.

Dozier says at the height of the pandemic, when schools were holding all events outdoors, she ran into Gilbert at her daughter’s prom, wearing what by then had become his trademark gold-toned shoes. “He says he wears those golden shoes for golden moments,” she says.

Online, there are pictures of Gilbert wearing the shoes at the opening of a park, a community event at a local mosque, a dance contest to benefit people with disabilities, and a party celebrating the town’s 150th birthday. He says he hopes the gold shoes make him feel approachable so people won’t feel intimidated to talk to him. They’re one small part of his overall strategy to listen, learn, and provide solutions.

Gilbert says he wants residents of Apex to know that he is there for them. At its core, he says, the role of mayor is not so different from that of a police officer. “Our campaign slogan was ‘People First,’” he says. “And that’s how I look at everything. It’s always about the people.”

The difference is, as a police officer, Gilbert was often working reactively, responding to a crisis or an isolated incident after it happened. As mayor, he can strategize and be more proactive. He can get closer to the root of things.

Supporters say Gilbert’s charisma is contagious, and the changes he’s making are genuine—a direct result of what he hears from his constituents. Officially, “it’s a part-time gig,” he says. “But for me, it’s a full-time job.”

“Jacques’ purpose, you can see clearly, is to help others,” Kopras says. “There is no rank with him. We are all equal. You can tell he doesn’t see himself better than anyone else. […] If we could mold him and create others like him, the world would be an incredible place.” Gilbert says he is especially proud that, under his leadership, Apex has increased its efforts to include and celebrate its Black communities. “We’re formally celebrating Juneteenth now,” he says. “And that was never the deal before. A walk for Martin Luther King Jr. Day? We never had that.”

With Gilbert’s influence, the entire town calendar has become more diverse. Apex now officially celebrates Pride Month, Hispanic Heritage Month, Hanukkah, and more.

While Gilbert speaks out on issues from traffic to housing to policing, his main job, as always, is showing up. Whether it’s a ribbon-cutting event, a town festival, or a football game between two rival high schools, he’s almost certainly going to be there.

And every Friday, he shows up somewhere in the town to knock on doors and ask people what they need from their local government. He includes town employees in these rounds.

“People get so laser-focused on what’s happening on Pennsylvania Avenue,” Gilbert says. “But when we ask them what we can improve on Salem Street [Apex’s main street], they know what we need. A pothole that needs fixing has no political affiliation.”

During his police force career, Gilbert says, he was often called to help people on their worst days. As mayor, he gets to be there for some of the golden moments too.

Written By Kim Painter