Long-Term Investors: Think like a Butterfly

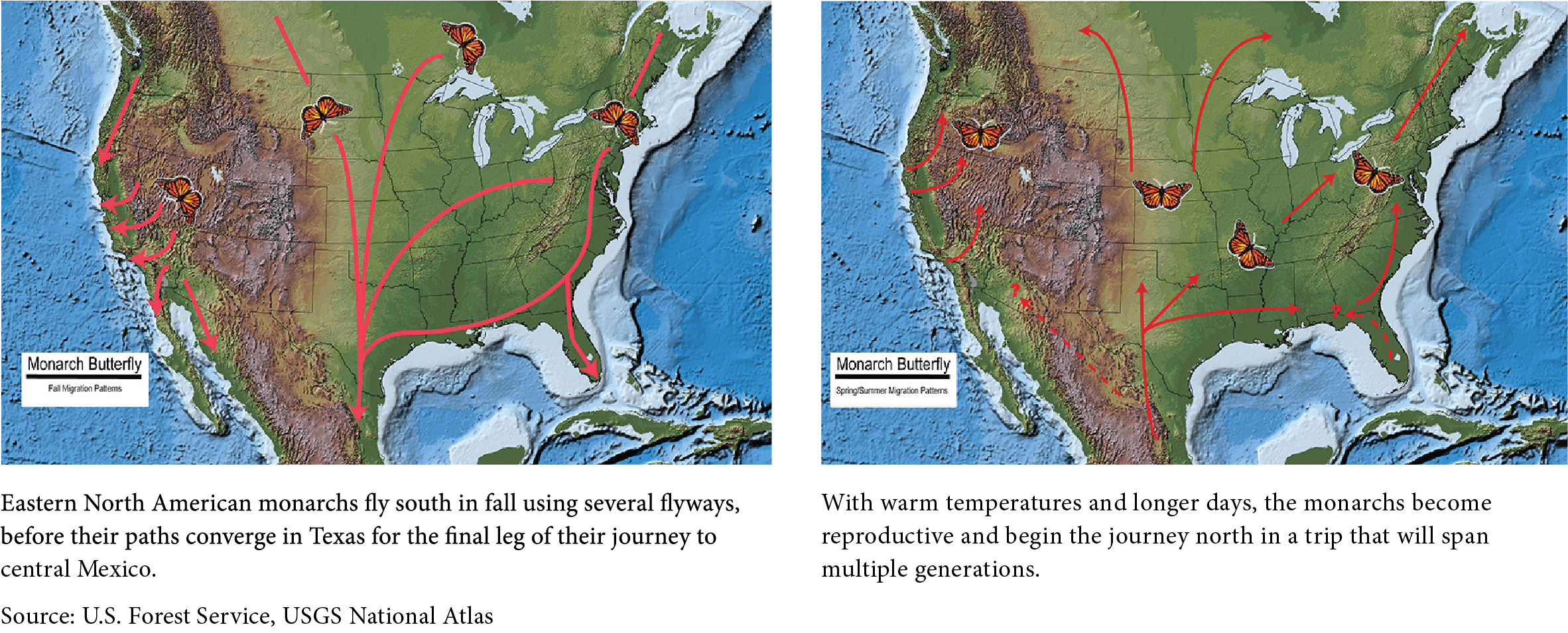

A good illustration of the long-term investing mindset comes from an unlikely source: the migration pattern and lifecycle of the monarch butterfly. In one of the most amazing feats of the natural world, each spring, these fragile insects migrate as much as 3,000 miles from a small mountainous region in central Mexico to as far north as the coastal Canadian province of New Brunswick.

However, no single monarch makes the trip—it can take up to four generations to travel the entire distance. Individual insects contribute and play their small parts knowing that, although they may not see the conclusion of the journey, a future generation will arrive safely at their destination to restart the cycle.

Environmental scientists have a term for this type of behavior: biological altruism. An organism is considered altruistic when its behaviors benefit its species at a cost to itself, as survival of the fittest makes way for the collective survival of the generous.

This analogy can be applied to the mindset of long-term investors, whether a private investor or family whose goals may extend far beyond their own lifetimes or an institutional investor, such as an endowment, foundation, or perpetual benefit plan. Altruistic investors will frequently be tested by their emotions and market volatility as they seek to provide security and opportunity to future beneficiaries.

The Long-Term Advantage

The first step in developing a long-term mindset is to recognize the unique advantages and risks posed to investors with multigenerational investment objectives, then designing approaches to optimize the former and manage the latter.

The long-term investor’s greatest advantage is his or her extended time horizon. This is particularly true when the investor has limited liquidity needs from the portfolio. Because such investors can focus on objectives measured over many decades, short periods of poor performance and market volatility have minimal impact and are barely noticeable. In this way, individual investors can learn from large institutional investors, such as university endowments, charitable foundations, and public and private sector benefit plans with long time horizons.

In fact, because institutional investors are typically governed by investment policies that specify portfolio target weights and rebalancing methodology in an unemotional way, studies have shown that endowments tend to invest countercyclically during times of crisis by paring allocations to risk assets during the run-up to a crisis and increasing those allocations during periods of market stress.1

One simple way that individual investors of all types can replicate this strategy is through the use of mental accounting. Instead of viewing and managing their investments as a single portfolio, investors divide their portfolios into several buckets with different risk, income, and liquidity profiles. For example, a three-bucket approach could include:

- Liquidity—contains a comfortable amount of cash and other highly liquid short-term securities to provide for current cash or spending needs.

- Income—a portfolio designed to satisfy near-term income needs via higher-yielding securities, such as credit-focused fixed income and dividend-oriented equity strategies, with an eye toward tax efficiency.

- Growth—a portfolio with higher expected risk and return for long-term growth potential. Investors will often maintain several such buckets earmarked for different objectives, such as college savings, retirement, and lifetime giving, as well as longer-term legacy objectives.

The presence of each bucket allows a longer-term perspective for each successive bucket. During times of market stress, the liquidity bucket provides the investor with the breathing room and time for recovery in the income bucket, and the income bucket reduces the liquidity required within the growth bucket. This strategy is also intended to be dynamic so that, over time, the relative weights of each bucket can be recalibrated to meet the investor’s current situation.

Long Journeys Require a Map

The annual monarch migration brings millions of butterflies, scattered across all corners of the North American continent, together to a few isolated mountains in the Sierra Madre range—a feat of navigation that biologists still don’t fully understand. Many (if not most) human beings, in contrast, require a map or smartphone app to navigate across town, let alone across long, never-before-traveled routes.

Although long-term investors measure their journeys in years (or decades) instead of miles, they still require a road map. For long-term institutional investors, this guidance takes the form of a comprehensive investment plan called an investment policy statement (IPS). This document is a powerful tool that establishes a set of guardrails and guidelines for the long-term management of investment assets, including the roles and responsibilities of the various parties involved, clear definitions of success and risk, asset classes and investment types allowed within the portfolio, and the target, minimum, and maximum weights of each category.

Individual investors can replicate this approach through the development of a comprehensive financial plan that considers all aspects of their financial lives, their near- and long-term goals, and how they will measure progress toward those goals. Such a plan should consider not only the preferences, constraints, and risk tolerance of the individual but also the nature of the risks that jeopardize long-term success, how sensitive the portfolio is to each of those risks, and how they can be managed.

To succeed, investors need to clearly define their goals, have an objective analysis of the strategy needed to accomplish them, and then a detailed plan for execution and ongoing monitoring.

Having such a plan also provides a systematic structure for managing emotions. Rebalancing to strategic targets allows investors to harvest gains, remain in balance when returns are strong, and add to positions when markets are challenged.

The Importance of Teamwork

Another example of animal altruism can be seen in the migration of Canada geese. While these birds may seem a bit mean-spirited and aggressive when encountered at a park or golf course, they exhibit incredible teamwork along their migration journeys. It’s well known that the key to their long-distance migration is the iconic V-formation that allows for much longer distances than any single bird could fly on its own. But when an individual bird is sick or injured, two other geese will fall from formation to help the injured bird until it either recovers and can rejoin the flock or dies.

Teamwork is also an important element of successful long-term investing. Other advantages enjoyed by institutional investors, such as endowments and foundations, are the presence of a team of professional investment staff or investment consultants and the oversight of an investment committee. These teams provide a diversity of ideas and perspectives that can help reduce one of the greatest threats to the long-term success of individual investors: the risk of emotional investing.

Teams of people provide a wide array of perspectives. Some members may be bullish and aggressive, while others may be more cautious. Some may seek specialized, alternative, or private investments in search of diversification and excess return, while others are laser-focused on keeping investment expenses low. The result in well-functioning committees is a diversification of emotions that helps temper the biases of any individual.

Individual investors can replicate these benefits by surrounding themselves with capable teams of advisors and professionals who bring a diversity of views but are all on the same page with regard to goals and objectives. It can also be important to include family members as part of the team to help build awareness and alignment with long-term goals and strategies.

Managing Long-Term Risks

Managing emotions is, without a doubt, the greatest challenge faced by any investor. This is true when markets are on a tear—leading to the temptation to take additional risk—but is particularly important when markets face challenges. Long-term investors must avoid the temptation to alter their investment strategies based upon current conditions. In other words, avoid market timing. However, this doesn’t mean that long-term investors should turn a blind eye to the markets, set it and forget it, and bury their heads in the sand.

Long-term investors should be far less interested in whether this year’s S&P 500 companies’ earnings estimates are 5 or 6 percent higher than last year’s or the current level of stock price valuations or investment-grade bond credit spreads. Rather, the focus should shift to structural changes within the markets and the economy that either pose risks to accomplishing their objectives or introduce new investment opportunities.

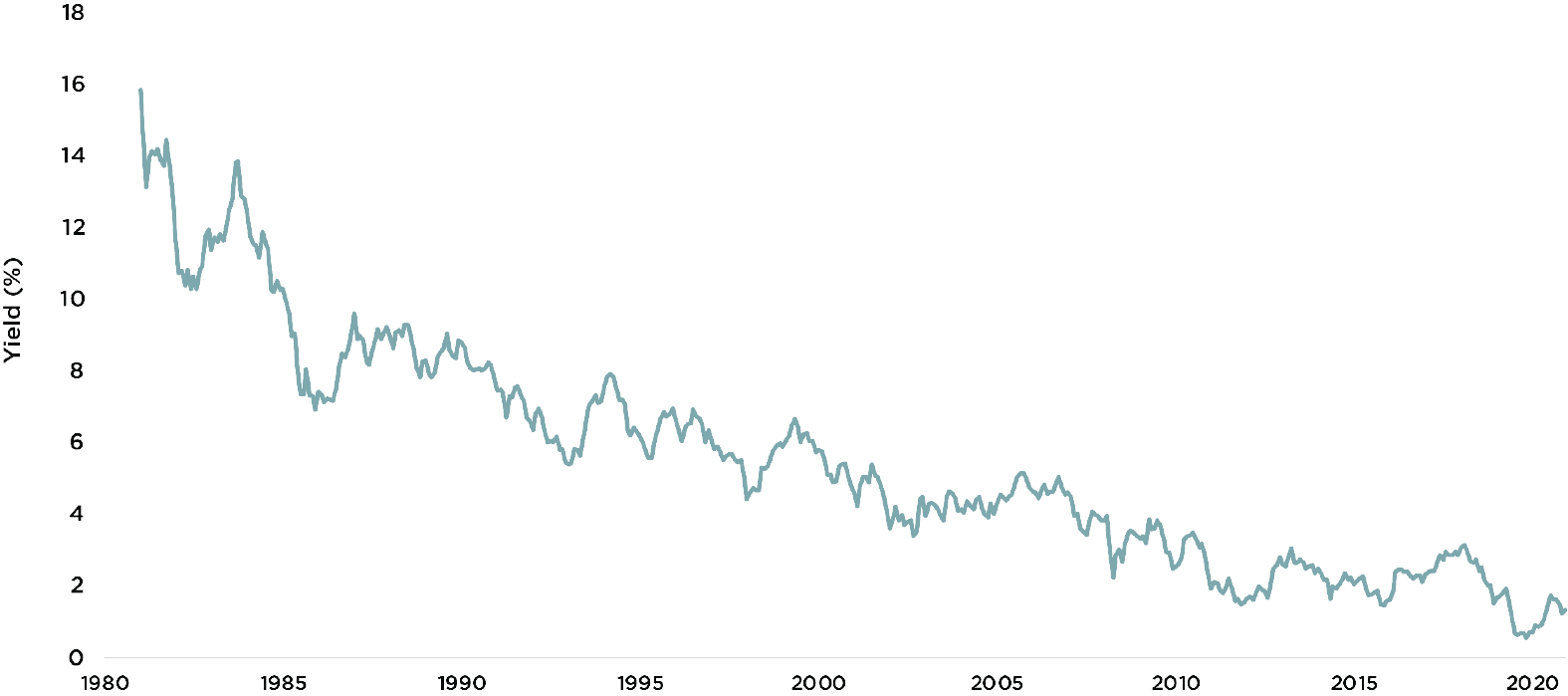

Capital market assumptions. Although the asset allocation of long-term portfolios should remain relatively stable, material shifts in the long-term risk and return expectations of asset classes, levels of inflation, and economic growth may influence how portfolios are designed for maximum efficiency and can point to the kinds of investment strategies that provide the greatest opportunities for success. For example, investing in fixed income today—after the 40-year secular decline in interest rates illustrated in Figure Two—should be different from the approach taken decades ago.

Figure Two: 10-Year U.S. Treasury Yield (1981—2021)

Sources: CAPTRUST Research, Bloomberg

Demographics. Perhaps no other economic force holds more power than demographic shifts. Consider the impact of the baby boom generation on the U.S. and global economy. Most of the largest countries are expected to see material declines in population in the second half of this century, along with major shifts in the age structure that may see the number of people over age 80 exceed those under age 5 by a ratio of two to one.2 More favorable demographic trends are expected to occur within emerging markets, albeit with heightened risks of political and economic instability.

Global conditions. One of the most significant trends of the past 50 years has been globalization and an increasing degree of global economic interconnectedness. This trend has contributed to corporate profitability and helped keep inflation low. However, it also presents increased risks of ripple effects of geopolitical or trade tensions, or economic, social, or political upheaval across the globe.

Inflation. Perhaps the most potent risk to long-term investors is the preservation of purchasing power over long time horizons. Stable and modest inflation also represents an important precursor to economic stability and growth.

Technology. Keeping an eye on technological shifts is critically important for long-term investors as a source of significant growth and obsolescence risk. Technology has permeated all aspects of our daily lives, and technology stocks now represent the largest component of the S&P 500 by market capitalization. This does not, however, imply that the long-term investor should chase every hot innovation. Indeed, many traditional, old-economy companies may see material benefits from improving productivity and efficiency through the application of new technology.

Evolving to Succeed

Not all animals are wired to demonstrate the same kind of altruism as the humble monarch butterfly. Some Antarctic penguins will shove their mates from the ice to ensure that the water is safe before taking the plunge themselves. Although this may improve the odds of group survival, it only works because penguins seem to lack the ability to hold a grudge. Another example can be found in the many species of animals that are known to eat their offspring—even species that, paradoxically, also care for their young.

Although it’s hard to understand this behavior, we must recognize that Mother Nature—with a time horizon of hundreds of thousands or millions of years to evolve behaviors that improve the odds of survival—is the ultimate long-term investor. Even if investment goals are only a few decades away, maintaining the right mindset, building a team and a plan, and continually monitoring for environmental threats and opportunities represent the best approach to arrive at your destination.

1 Chambers, Dimson, Kaffe. “Seventy-Five Years of Investing for Future Generations,” Financial Analysts Journal, vol. 76, no. 4, Fourth Quarter 2020

2 “Global population in 2100,” The Lancet, 2017