Only the Essentials

Although Thoreau is inspirational, his actions are difficult to emulate. Most people cannot quit their jobs, give up most of their friends and possessions, and build a cabin in the woods with their bare hands.

What they can do is simplify the patterns of their lives to make things more manageable and meaningful. This is something Greg McKeown has studied extensively for more than a decade.

McKeown is a New York Times bestselling author of two books: Essentialism: The Disciplined Pursuit of Less and Effortless: Make It Easier to Do What Matters Most. He says it’s natural for people to assume that the solution to feeling overwhelmed is to escape, do less, or become more efficient. His philosophy, essentialism, rejects those options.

“Essentialism isn’t about getting more done in less time, and it doesn’t mean doing less for the sake of less,” says McKeown. “Essentialism is about getting only the right things done. It’s about making the wisest possible investment of your time and energy in order to operate at your highest point of contribution by doing only what is essential.”

Creating Alignment

The first step in becoming an essentialist is to determine your personal values and goals. Think of this as if you are writing a business plan for the next five years. Name your mission, vision, and core values. To begin, “Ask yourself, What is essential?,” McKeown says. “Then figure out what you need to say no to.”

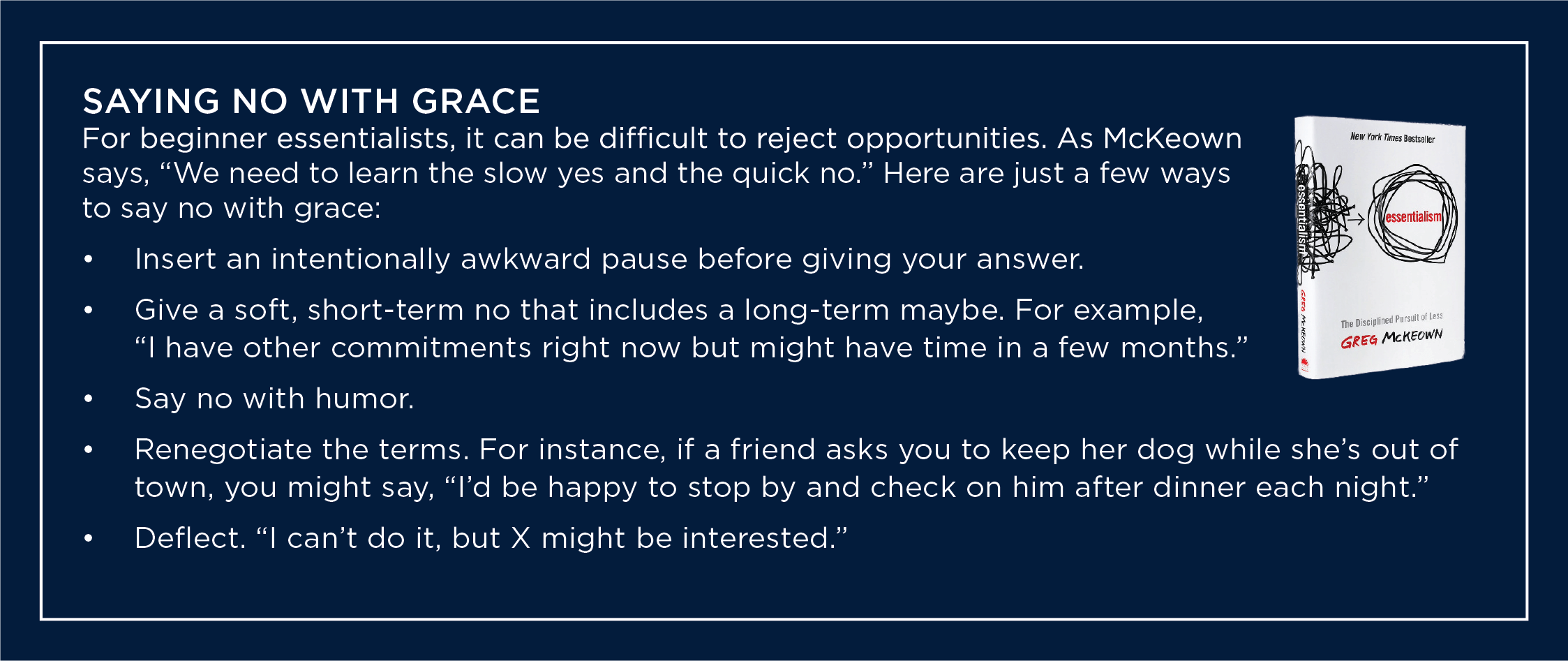

Learning to say no strategically is a key tenet of essentialism. With almost limitless options for how to spend money and time, McKeown says it helps to remember that every choice also carries an opportunity cost. Each decision means shutting a door and making a trade-off. And that’s a good thing.

“Trade-offs are not something to ignore or avoid; they are something to embrace and explore,” says McKeown. By consciously accepting trade-offs, people can let go of nonessential distractions and focus on what truly matters to them. When there are fewer options available, it’s easier to create alignment between your daily actions and long-term goals.

This seems simple on paper, but it can be tricky in real life. For example, let’s say you’ve defined your values as family, faith, and self-care. A friend asks you to help organize a community litter pickup event on an upcoming weekend. You have nothing planned for those days. It’s a worthy cause, and volunteering is important to you. But it isn’t one of your essentials.

By saying no, you could create time to do things that better align with your essential values: taking a long walk with your grandchildren, for instance, or simply writing a letter to a friend. Or you could say yes, bring your grandchildren along, and use the physical activity that litter pickup entails as a form of exercise and self-care for the day.

How do you know which is the correct response? “If it isn’t a clear yes, then it’s a clear no,” says McKeown. In other words, follow your gut.

“Nonessentialists get excited by virtually everything and thus react to everything,” McKeown says. “But because they are so busy pursuing every opportunity and idea, they actually explore less.” Essentialists commit to deep exploration of what McKeown calls “the vital few” versus “the trivial many.”

By Design, Not Default

However, McKeown warns, because social expectations encourage busyness, multitasking, and hyperproductivity, even people who know their vital few can get distracted over time by exciting but nonessential opportunities. That’s why the next step is so important.

Essentialists don’t just commit to the essentials. They structure their daily lives around them.

“To get it right, we have to build essentialism into the design of our lives so that we make it easy for ourselves to prioritize what matters to us, instead of having somebody else decide what we will prioritize,” says McKeown. This means breaking ingrained patterns to live by design, not by default.

For McKeown, play and sleep are two key examples. While the nonessentialist often gives up play and may sacrifice a few hours of sleep to be more productive, essentialists know that play and sleep are necessary to reach their highest potential. So they set aside time each day for both.

“Routine is one of the most powerful tools for removing obstacles,” says McKeown. “Without routine, the pull of nonessential distractions will overpower us. But if we create a routine that enshrines the essentials, we will begin to execute them on autopilot.”

Regardless of what your essentials are—work, travel, fitness, time outside, improving your community, learning a new skill, or more— building your schedule around these priorities will help you keep focused and accomplish what really matters to you. “Almost everything is noise,” McKeown says. “Only a few things really matter.”