Putting Money Habits to Good Use

The habits that we’ve formed over our lifetimes help define us. We have physical habits, mental habits, habits of character, personal hygiene habits, and productivity habits. We have good habits, and we have bad habits.

Habits are automatic—almost involuntary—behaviors. Actions that happen so automatically, we often don’t recognize they are there. All told, about 40 percent of our daily activities are performed each day in almost the same situation.1 These activities make up our personal collections of habits.

Compounding Results

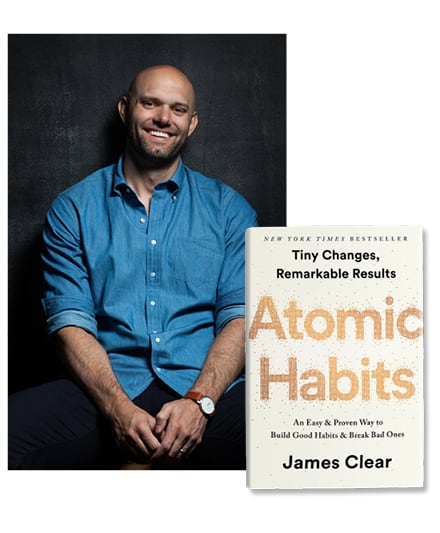

James Clear, author of Atomic Habits: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad Ones, became an evangelist on the topic when a freak baseball accident sent him to the hospital with serious injuries to his face and brain. His long road to recovery led him to believe that creating small, simple habits can bring about powerful change over time.

Clear makes the case that individuals can harness the power of these incremental behavioral changes to affect improvements in their productivity, physical well-being, business, and social lives. “Habits are the compound interest of self-improvement,” says Clear. “The same way that money multiplies through compound interest, the effects of your habits multiply over time and as you repeat them.”

And like compound interest, the impact of these tiny changes is difficult to grasp in the short term, but the difference they make over months and years can be enormous. “It’s only when looking back two, five, or 10 years later that the value of good habits and the cost of bad ones becomes striking,” says Clear.

Comparing these incremental changes to compounding—what Albert Einstein supposedly called the “most powerful force in the universe”—has its merits. But is it possible to apply Clear’s ideas to compound interest itself? In other words: Can we make our money multiply faster by creating new, positive money habits—or by cutting out a few problematic ones?

Clear’s answer is, um, clear. “Your net worth is a lagging measure of your financial habits.” Good financial habits create good outcomes; bad financial habits create bad outcomes, he says.

The Power of 1 Percent

Clear believes in thinking small. Small changes are easier to make—and easier to stick with—than bold, life-changing moves. And small changes in your daily habits can guide your life to a very different destination.

“Making a choice that is 1 percent better or 1 percent worse seems insignificant in the moment, but over the moments that make up a lifetime, these choices determine the difference between who you are and who you could be,” says Clear.

If you got 1 percent better every day for a year, after a year, your results would be 37 times better.

Of course, there’s a dark side as well. “When we repeat 1 percent errors, day after day, by replicating poor decisions, duplicating tiny mistakes, and rationalizing little excuses, our small choices compound into toxic results,” says Clear. “If you’re a millionaire but you spend more than you earn each month, then you’re on a bad trajectory; if your spending habits don’t change, it’s not going to end well.”

Decoding Habits

Unless you’re a habit nerd like Clear, you probably haven’t pondered the habits that make up your daily routine. Many habits are ways to automate chores: fastening our seatbelts when we get behind the wheel, pulling out a credit card when the dinner check arrives, and brushing our teeth after flossing. They help us get things done using minimal mental energy so we can focus on more important things.

Habits are small but mighty behaviors made up of four simple steps. “If a behavior is insufficient in any of the four stages, it will not become a habit,” says Clear. The four steps are:

- Cue. A cue is an environmental trigger that prompts you to execute a habit. Habits can be triggered by time, place, emotional state, people, or something that just happened.

- Craving. Cravings are the motivation behind habit. Our desire for a change in state—a relief, reward, or release—is what moves us.

- Response. The response is the habit that you perform. It’s the way you scratch the itch to satisfy the craving.

- Reward. The reward is the goal of every habit, and achieving the reward further ingrains the habit.

That seems a little abstract and impersonal, so let’s bring it to life.

Sitting in your favorite chair after dinner with the TV remote control near your right hand is a cue. You crave entertainment. You respond by reaching for the remote and tuning the TV to your favorite channel. You are rewarded with an emotional news story, a cathartic true crime mystery, or 60 minutes of reality show drama. And by satisfying your craving, the success of closing the habit loop reinforces the habit itself. Over time, you become an evening TV watcher.

“Every action you take is a vote for the type of person you wish to become,” says Clear. If you aspire to be an evening TV watcher, more power to you. But if you’d rather be a better father, guitarist, or Spanish speaker, spending your evenings watching TV is stealing votes from those goals.

That’s why it makes sense to pay attention to your habits and build the right ones. And the sooner the better.

More Money, More Habits

Many of us have developed quite a few bad money habits, and it’s understandable why. We are bombarded by ads that urge us to buy a new car, go to the Caribbean, eat out, buy an exercise bike, and so on. These things or experiences confer status on us, which is a feeling we crave. But these expenditures drain our paychecks and savings accounts when we respond.

Therein lies the problem: Many bad money habits provide instant gratification. Meanwhile, good money habits feel like sacrifices. You’re giving something up today for the future gratification.

But it is possible to end bad money habits. It just takes a little work.

“One of the most practical ways to eliminate a bad habit is to reduce exposure to the cue that causes it,” says Clear. “For example, if you’re spending too much money on electronics, quit reading reviews of the latest tech gear.” Or replace undesirable habits with beneficial habits that provide similar benefits. Over time, these new habits will tend to crowd out the bad ones.

Here are a few examples of good money habits—and the kind of

1 percent changes you can put in place today—to crowd out your bad habits:

- Always pay in full. Open and pay your credit card bills as soon as they arrive. Pay them off each month if you can—or better yet, only pay with cash or debit card. It may hurt at first, but you will grow to love it.

- Auto-pay your bills. Set up automatic payment for your monthly household expenses. You have more important things to think about.

- Automate your savings. Set up an automatic draft to build an emergency fund. Try to max out your health savings account (HSA) and employer retirement plan every year. Start small and increase your contributions annually.

- Eliminate an expense. We all make small, habitual purchases that can add up. Find one that you can lose. Drop your daily latte habit. Then downgrade your super-premium cable subscription.

- Delay a major purchase. Is your two-year-old iPhone really obsolete? Do you need a new car every three years? Try delaying major purchases—even for a few months. The benefits add up over time.

“These one-time choices require a little bit of effort up front but create increasing value over time,” says Clear. The growing impact of these changes will flip the script and soon won’t feel like sacrifices. “You can associate it with freedom rather than limitation if you realize one simple truth: Living below your current means increases your future means.”

Clear cautions that even when you know you should start small, it’s easy to start too big. “You want to take on the smallest possible behavior that gets you moving in the right direction.” He suggests using the Two-Minute Rule, which states, “When you start a new habit, it should take less than two minutes to do.”

“The idea is to make your habits as easy as possible to start,” says Clear. “A new habit should not feel like a challenge; the actions that follow can be challenging, but the first two minutes should be easy.”

1 Society for Personality and Social Psychology, “How We Form Habits, Change Existing Ones,” ScienceDaily, 2014

James Clear: Best-Selling Author and Habit Nerd

James Clear is the author of The New York Times bestseller Atomic Habits: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad Ones, which has sold more than one million copies since it was published in 2018. Packed with evidence-based self-improvement strategies, Atomic Habits shows readers how to use small changes to transform their habits and deliver remarkable results. Clear’s work has appeared in The New York Times, Entrepreneur, Time, and on CBS This Morning. His website receives millions of visitors each month, and hundreds of thousands subscribe to his popular email newsletter at jamesclear.com. He is currently at work on his next book.