Remorse Code: Unraveling Regret

This long-awaited letter ended with an admonition: “Our residence halls are already full. Attached is a list of off-campus housing we suggest for first-year students.”

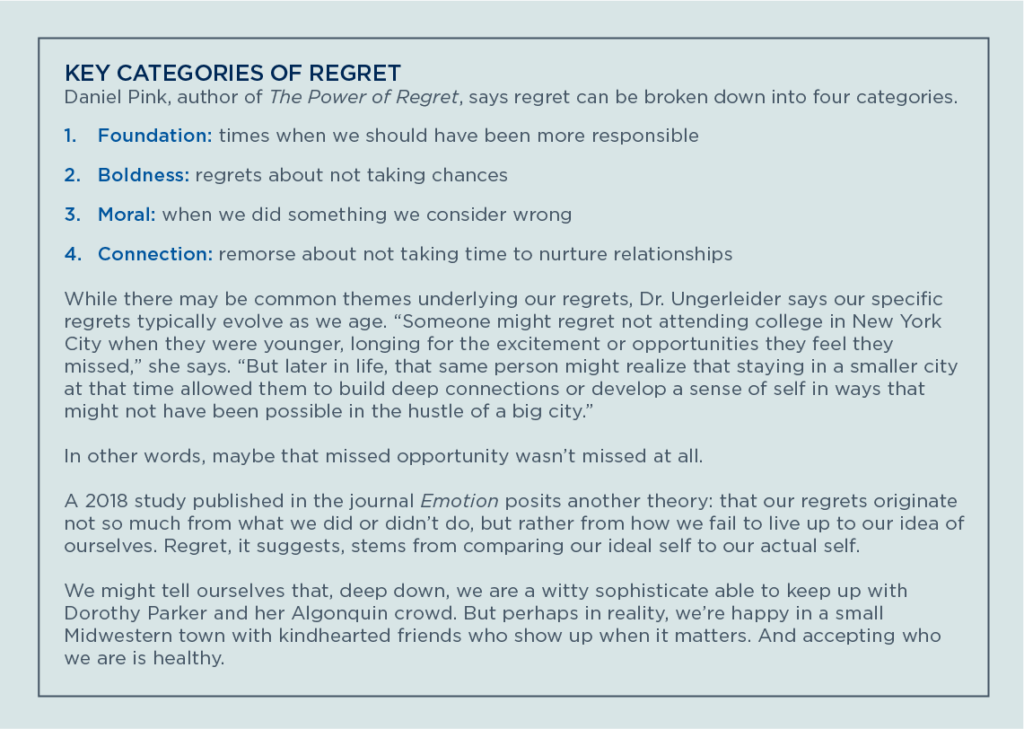

Gardener, now 58, had dreamt of living in New York City since she’d first learned about Dorothy Parker’s Algonquin Round Table lunches of the 1920s. Nearly every day, Parker joined other writers, critics, and actors at the Algonquin hotel for food, barbed humor, and sophisticated takes on life.

It formed Gardener’s image of—and yearning for—New York. For her, it was home to the witty, the fashionable, and the egg cream, whatever that was. She couldn’t wait to find out.

But her acceptance letter to NYU ended up in a drawer, never to be answered. “Maybe if there had been a residence hall to live in, I’d have taken the chance,” says Gardener. “But just to be out there in New York on my own? It suddenly felt too scary.”

Gardener attended nearby Michigan State University instead, where she won a scholarship to study in London for a summer, graduated with honors, and, incidentally, met her husband.

Still, Gardener says she has always regretted not going to school in New York.

Where Does Regret Come From?

Regret is the heavy feeling we get when we picture how things might have been if we’d made different life choices. When the feeling arises, research shows that two specific areas—the amygdala and the medial orbitofrontal cortex—are activated in the brain. This same brain activity also shows up in animals, who need to experience regret for survival.

While these pangs of conscience can affect us physically, causing symptoms like muscle tension, headaches, and even a weakened immune system, they also can be a healthy part of self-learning and growth, helping people move on from poor decisions.

What Do We Regret Most?

Dr. Shoshana Ungerleider is an internal medicine physician, host of the podcast Before We Go, and founder of the nonprofit End Well, which strives to reshape negative attitudes toward death and dying.

Over the years, Dr. Ungerleider has heard the deathbed regrets of several patients. These regrets seem to have two common themes: being afraid to take chances and focusing on the wrong things. Specifically, she lists them as:

- not spending enough time with loved ones;

- working too much;

- letting fear control decision-making and risk-taking; and

- focusing too much on the future instead of enjoying the present.

No Regrets

What about people who aren’t bothered by these kinds of feelings and claim to live without remorse? These are the folks who may proudly sport bumper stickers, t-shirts, even the occasional tattoo proclaiming “No Regrets.”

For people who have experienced injury to their medial orbitofrontal cortex, this may be true. Damage to that area of the brain can make it impossible to feel regret. But aside from having a brain injury, is it possible to live a life without remorse?

Dr. Ungerleider says that those who claim to live without regrets are usually expressing a desire to feel at peace with their choices. But this attitude can sometimes prevent people from engaging in meaningful self-reflection and personal growth.

“As someone who has worked with patients at the end of life, I’ve come to realize that the notion of living with no regrets is often an oversimplification of the complex human experience,” says Dr. Ungerleider. “While it’s admirable to strive for a life well lived, the reality is that regrets are a natural part of our journey.”

Acknowledging that we have regrets doesn’t diminish how we have lived, she says. “Instead, it can lead to profound moments of insight, reconciliation, and even personal transformation.”

Living with Regret

Self-compassion is a great way to begin to embrace regret. Instead of rehashing your mistakes, acknowledge that you did the best you could with the knowledge and resources you had at the time, says Dr. Ungerleider. “Treating yourself with kindness can shift the narrative from blame to understanding, allowing those painful moments to feel less overwhelming.”

Also, try to live in the present. When you dwell on past decisions, you are sending electricity to your medial orbitofrontal cortex. Do this often enough, and you create a well-traveled electrical pathway that can make you feel stuck or like you’re not in control of your thoughts. Instead, look forward to the choices ahead of you, which can be guided by what you’ve learned so far.

“It’s never too late to learn from regrets, no matter how old we are,” says Dr. Ungerleider. “Middle age and beyond offer a unique opportunity to reflect on past experiences with greater wisdom.

“While we can’t change the past, we can change how we respond to it, finding ways to reframe regrets and use them as a catalyst for growth,” she says. “What matters is how we interpret and integrate those experiences into the story of our lives, allowing us to embrace both the paths we’ve taken and the ones we haven’t.”

By Karen Sommerfeld

For more than a decade, Karen Sommerfeld has written content for the finance industry. She’s drawn to the behaviors and emotions around money. Karen joined CAPTRUST in the spring of 2024 as a marketing specialist. E.B. White inspired her retirement dream, which is to run a farm animal sanctuary.