A Debut Novel at 70: How Anne Youngson Wrote Her Own Plot Twist

“He read it and told me, ‘I wish I were writing this,’ which I thought was just about the nicest thing anyone ever said to me.” Soon after, the advisor introduced her to a literary agent, who introduced her to a publisher, who immediately asked to buy the rights to her manuscript—and that is how Youngson’s first novel, Meet Me at the Museum, came to be.

It was an unexpected cascade of events. She was 69 years old.

In the eight years since, Youngson has published three more books and written dozens of stories. Mostly, she writes about transformation. “I wanted to study the idea that, whatever your age, if things aren’t right, if there are things you want to explore, or if you want to bring change to your life, you can still do it.”

At 76, Youngson speaks from experience. She didn’t start writing seriously until she was in her 60s.

The Rover Years

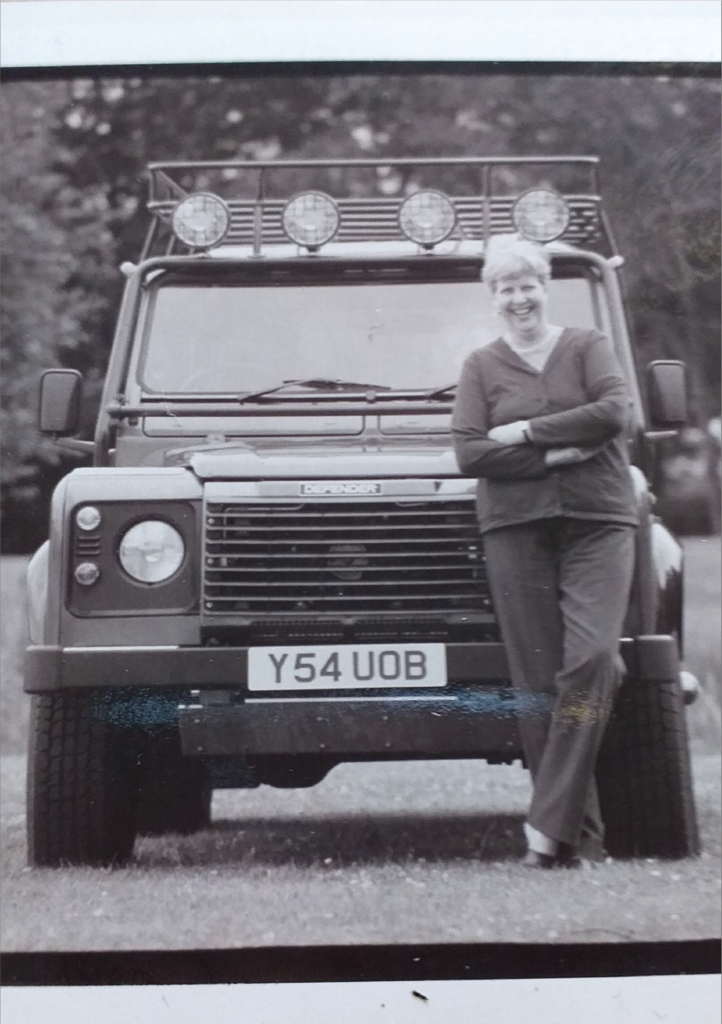

Before she became a published writer, Youngson worked for the British car company Land Rover, climbing steadily over 33 years to chief engineer of the Defender brand and managing director of special vehicle operations. It was a surprising path for someone with an undergraduate degree in medieval English. But Youngson says her transition from humanities to engineering was intentional.

“When I left university, I didn’t want a job involving English literature because I felt that I’d come out of school without any practical skills,” she says. “I wanted to tackle problems that were open to practical analysis.”

She took an entry-level role in the marketing department at what was then called British Leyland Motor Corporation but soon realized the only place she could have fun was in engineering. “In vehicle manufacturing, it’s the engineers who shape what the company does,” she says.

So Youngson worked her way over to the engineering department and then rose through the ranks to the executive level. It was a highly technical environment, and her team was almost entirely male.

Despite the ways she differed from her colleagues, Youngson says she rarely felt like an outsider and loved changing from job to job within the company. “I had quite a satisfying and varied career, which I suppose is why I stuck it out for so long,” she says. “But I have to say, when I started, I always thought, I’m just going to do this until I write my novel.”

One of her closest colleagues at Land Rover was engineer Nick Seale. He and Youngson worked together on joint vehicle projects, designing cars in collaboration with Honda and BMW.

Seale says he can see how Youngson’s corporate skill set contributes to her success as a writer. “We worked on some very, very big projects with large teams and lots of different aspects,” he says. “Anne didn’t have a technical background, but she knew how to listen and learn from others. She’s a brilliant listener, which is not at all common. She listened to understand people’s points and then balance them with each other.”

But his favorite thing about working with Youngson was her consistent humility. “She has no ego,” Seale says. “She was never pushing her own feelings onto people and pulling them into accepting them. Instead, she’d say, ‘I don’t know what the technical solution is, so let’s listen to all the views and figure it out.’ That gets people on your side.”

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, when the Rover Cars division was working with Honda, “product development between a Japanese company and a British company was basically unheard of,” says Seale. “There was no road map. There were no preexisting legal agreements. Throughout, it was very important to balance people’s conflicting views and ways of doing business.”

Youngson and Seale enjoyed learning the cultural difference between teams. And Seale says Youngson’s ability to listen and then speak plainly and honestly became a critical part of the collaboration.

From Engineering to Sweet Peas

A few years after Ford bought Land Rover in the early 2000s, the company offered Youngson a nice retirement package. But at only 56 years old, she felt too young to stop working. She was worried about losing connections and not feeling fully engaged in the world.

To sort out her feelings, she made a list of all the things she could do if she retired. “Some of them were really silly, like growing sweet peas,” says Youngson. The more time she spent looking at the list, the more excited she felt about retiring.

She also felt this was the time to finally get serious about her writing. “I’d written all the time but only little stories for myself,” she says. “I wasn’t really taking it seriously. And I thought, well, now’s the time to explore.” Eventually, she accepted Ford’s offer.

Figuring Out Retirement

That first year was stressful and disorganized. “I was a bit panicked,” Youngson says. “When you’re working, you know what to expect. You know you’ll have however many emails to answer each day and a full schedule, but all of that had gone away. I wasn’t getting any emails at all, except from people telling me how to invest my retirement funds.”

To fill the time, Youngson signed up for lots of volunteer opportunities and worked in governance for multiple nonprofits. “And all the time I was writing,” she says. “Then one day I realized my calendar was as full as it ever was, and nobody was paying me!” She decided to make a change.

To focus her energy, Youngson enrolled in a two-year evening course in creative writing at Oxford University, just down the street from her home in Oxfordshire, England. She went on to earn a master’s degree and then a doctorate. “Every time I did a course, I was really stimulated,” she says. “I was writing away. But then I’d gradually just sort of run out of impetus, so I’d think, OK, time to do another course! And finally, I ended up with a PhD.”

Friends and Feedback

There’s an old idea about artistic jobs like writing, painting, and musical composition that says talent is innate. It can’t be taught or learned, so taking classes is pointless. Youngson found that idea both true and false.

“I don’t think any of the courses I’ve taken have actually taught me anything,” she says. “What they’ve done is enable me to understand what I’m already doing and how I can do it better.”

She says another benefit of going back to school is that she made unlikely friends. “I thought the biggest danger of retirement is that you end up mixing with only the same people all the time—people who think like you and live like you because that’s who your friends are.”

Enrolling in courses was a way to meet people who weren’t in their 50s or 60s and retired. “But still, in that first class, when we went around the room introducing ourselves, I found myself thinking, What am I doing here? These people are nothing like me!”

Over time, four of those classmates became her closest writing friends. They’d meet monthly to review each other’s work. Almost a decade later, they still meet three or four times a year. “Being part of a community of people who are writing seriously and giving you feedback on your work? I think that’s invaluable,” says Youngson. “I feel privileged to have met them.”

One member of this writing group is Bev Murray, a business psychologist and coach who turned to writing after her first child was born to add “a stream of creativity” to her life.

For Murray, Youngson is both a friend and an inspiration. “There’s so much humor, intelligence, and generosity in Anne, and these things come through in her writing.” She says Youngson has a special ability to interpret human nature and experience.

Although the media often attributes this competence to Youngson’s age, Murray says that message obscures the magic in her friend’s success. In 2018, when Meet Me at the Museum was nominated for a Costa Book Award for Best First Novel, the headlines almost never failed to mention that 70 is a surprising age to make a debut.

“I worry that, in the wider world, Anne’s age gets attention because it is seen as being so unusual,” says Murray. “From my perspective, she would have been successful no matter when she started writing. Her work shows her experiences in the world and her level of understanding of what she has experienced. Her age may be a part of that, but I have plenty of older friends who do not demonstrate the same level of understanding.”

Seale agrees. “Anne can read people,” he says. “It comes out of seeing that there are other ways of doing things and thinking.”

Although Youngson’s books often feature people who are middle-aged or older, her characters are focused on the future, not lost in their own reveries on aging. Youngson says this, too, is intentional.

“An awful lot of novels feature older people who are either used as plot devices—you know, a contrast to whatever is going on in the lives of the younger people—or they’re looking back,” she says. “They’re so often going back into the past to understand how their lives ended up where they are. I would read those and think: But you keep on living!”

Always Looking Forward

For Youngson, this is key to understanding human nature, aging, and good storytelling. “This is what you don’t understand when you’re younger is that you just keep on living,” she says. “Every day, you’re looking forward to something. It’s what we do as human beings. We’re always looking forward to something, even if it’s only tomorrow’s breakfast.”

It may also explain how Youngson has kept her positive attitude about change. “I’ve always believed that tomorrow is going to be at least as good as, if not better than, today.”

Part of her optimism was a driving belief that, one day, she would finally find the time to take her writing seriously. “I always knew the time would come,” she says. “It’s like I was saving it up as a treat until I had the time and headspace to really enjoy it.”

And now, she does.

Article by Roxanne Bellamy. Photos by Azul Photography.