The State of Estate Tax

The Biden-Sanders Unity Task Force Recommendations on the Biden campaign website say that estate taxes should be raised back to the historical norm. In other words, if Biden has his way, estate taxes would increase. That means more of a person’s estate would go toward federal taxes, leaving less for heirs and other beneficiaries.

Even if such a plan were to fail in Congress, there’s another issue to consider: The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. That law, enacted in December 2017, more than doubled the amount of assets that can be shielded from the federal estate tax and its companion, the federal gift tax. But those provisions apply only for estates of decedents dying (and gifts made) before January 1, 2026. After that, the old, less-generous provisions return.

Then there’s the coronavirus. Much of the money the federal government has spent fighting the coronavirus—and stimulating the economy—has been borrowed. At some point, the debt must be repaid—and the federal estate tax is an easy target for raising revenue, says Financial Advisor Brodie Barnes, who works in CAPTRUST’s Salt Lake City, Utah, office.

If you have a sizeable estate, consider taking advantage of current law by reducing the size of your estate to minimize how much may be eaten up in federal taxes later on, Barnes says. “Make moves now, because things are going to change one way or the other,” he adds.

Background

When a person dies, that person’s estate may be subject to federal estate tax. The federal gift tax operates alongside the estate tax to prevent individuals from avoiding the estate tax by transferring property to heirs before dying, according to a Congressional Research Service report.

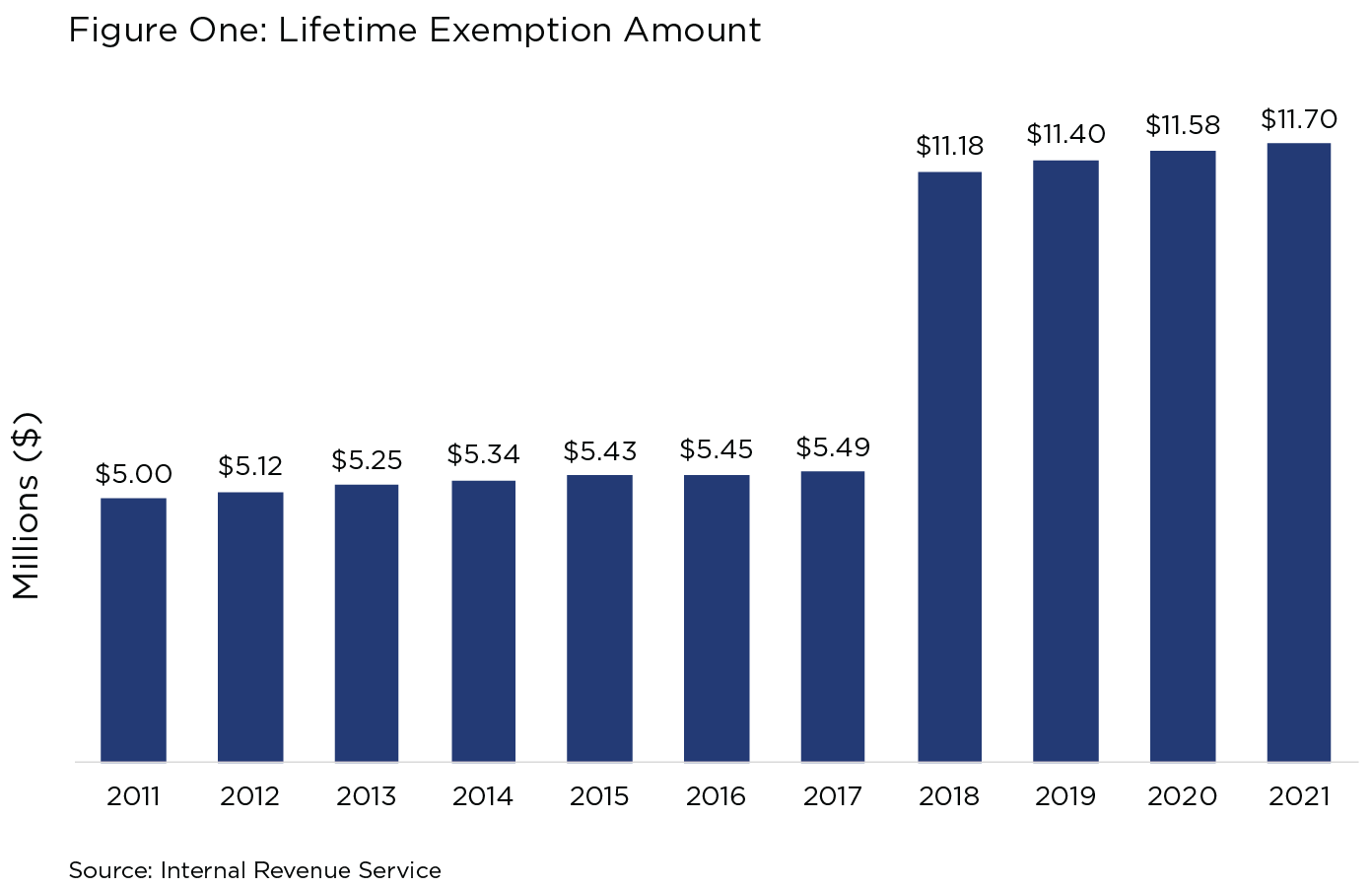

There is, however, a lifetime exemption amount. It serves to shield a certain amount of assets from both the federal gift tax and the federal estate tax. That lifetime limit, which is subject to an annual inflation adjustment, is $11.7 million for 2021, as shown in Figure One.

And there’s the rub. Under Biden’s plan, the lifetime limit would be reduced to what it was under the old law—somewhere around $5 million. Even if Congress were to reject such a plan, the lifetime limit, under current law, is scheduled to drop to an inflation-adjusted $6.5 million starting in 2026, Barnes estimates.

That’s why he recommends taking advantage of today’s higher lifetime limit. By giving away up to $11.7 million now, you move that amount out of your estate, perhaps transferring it to your children or other beneficiaries. Neither that amount, nor any future appreciation, will be subject to federal estate and gift taxes.

Suppose you do this now. When the lifetime limit drops in 2026 to about $6.5 million, will you be penalized for gifts you previously made? No. The Internal Revenue Service has officially stated that individuals taking advantage of the higher lifetime limit in effect until 2025 will not be adversely impacted after 2025 when the limit drops to prior-law levels.

Basic Steps

Before considering more complicated maneuvers, remember that you can give away a certain amount each year with no federal gift or estate tax consequences—and without even touching your lifetime limit. It’s technically known as the annual exclusion for gifts, and it’s subject to an annual adjustment for inflation. For 2021, the annual exclusion amount is $15,000, says Patricia A. Thompson, former chair of the Tax Executive Committee of the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants and tax partner at Piccerelli Gilstein & Company, LLP, of Providence, Rhode Island.

That means, for example, in 2021, you can give $15,000 to your son, $15,000 to your daughter, $15,000 to your longtime friend, and $15,000 to your helpful neighbor—for a combined total of $60,000.

If you’re married, each spouse may give up to $15,000, says Thompson. So you and your spouse can give a total of $30,000 to your nephew and a total of $30,000 to your niece for an overall total of $60,000, she says.

In each example, you’d move $60,000 out of your estate, legally sidestepping federal estate- and gift-tax consequences.

Another basic technique involves paying for someone’s education or medical expenses. There’s no dollar limit, and the beneficiary need not be related to you. But it’s important to make sure that you make the payment directly to the educational institution or healthcare provider, Thompson says.

For example, you can pay for your grandson’s law school tuition, no matter how much that is, and pay for your old friend’s medical expenses, no matter how much that is. In both instances, you would reduce the size of your estate; there would be no federal gift-tax and no federal estate-tax consequences, and you would preserve your lifetime limit of $11.7 million.

Other Options

Beyond the basic steps, consider making outright gifts to family members or others, up to the amount of your lifetime limit. This will reduce the amount of your estate that will eventually be subject to the federal estate tax—and its tax rate of 40 percent or more.

Suppose a widow has $50.3 million in assets. If she gives away an amount equal to her lifetime limit ($11.7 million in 2021), no federal gift taxes or estate taxes would apply, and she’d be left with $38.6 million to live on, Barnes says.

Some of his clients have no problem giving away large sums, he says. Others are reluctant, perhaps concerned that they may need the money later on. For them, Barnes recommends other options with more flexibility.

For example, you could make a gift to a spousal lifetime access trust, he says. That would let you move money out of your estate—taking advantage of your lifetime limit—but the assets in the trust would still be available to your spouse and other beneficiaries, such as your children, he says. To maximize this strategy and avoid certain pitfalls, he says, you could establish such a trust one year, to benefit your spouse and others; your spouse could establish such a trust the next year, to benefit you and others; and each trust would hold different kinds of assets.

Another option: Put some of your assets into a family partnership or family limited liability company, Barnes says. You could give your children an ownership stake in the entity, while you maintain overall control. The assets’ value and any associated appreciation would be removed from your estate.

The Right Fit

There are charitable options to consider, too, Thompson says, “but the client has to be comfortable giving his or her money away,” she says.

Any strategy should be part of an overall plan, and “it really needs to be customized to a client’s specific objectives and comfort level,” Barnes says. When considering such steps for clients, he says he looks at the client’s need for cash flow, the client’s charitable objectives, the type of assets the client holds, the client’s tolerance for complexity (and ongoing costs), and family dynamics. As always, before you implement any of these strategies, you should consult a tax advisor who can help you understand how they work and how they might best work for you.