The Emotional Values of a Dollar

No matter how sophisticated their investment knowledge, investors of all kinds are prone to make suboptimal choices, second-guess long-term decisions based on short-term occurrences, and lose sleep over investment portfolios. These are natural and understandable behaviors, but they’re rooted in a faulty assumption: that all dollars have equal value.

What is the actual value of a dollar? The obvious answer is 100 cents. However, this purely financial assessment fails to account for emotional attachment. There are, essentially, four different types of dollars investors encounter, and each has a different emotional value. Failing to understand the differences among the four has disrupted many well-designed investment plans.

Theoretical Dollars

The first type of dollar is one that investors often meet at the beginning of their investment journeys. These are purely theoretical dollars. They exist only in statistical models. Still, they’re important because they help establish expectations for long-term returns and short-term setbacks that could happen along the way.

Theoretical dollars are the foundation of all strong investment programs and financial plans. Using complex modeling tools and customized investor data, advisors can demonstrate a range of future outcomes that shift, depending on interim inputs. The future net worth they estimate, minus your net worth today, is composed entirely of theoretical dollars. At best, these dollars have no emotional value. At worst, they can be misleading—especially if we let ourselves get emotionally attached.

It’s difficult for the human brain to forecast feelings of loss. Visualizing joy is much easier. That’s why, although we often underestimate how we will feel after a surprise market dip, we can easily slip into daydreams about spending our theoretical dollars at age 70, when we’re on a beach somewhere with our loved ones.

Theoretical dollars are important, but keep in mind, they are not real.

Statement Dollars

As investors successfully navigate their journeys, theoretical dollars gradually become statement dollars. These are real dollars, built by discipline, sacrifices, and time. But they are invested, illiquid, and hopefully, growing. The effort required to accumulate these dollars creates a connection that gives them emotional value.

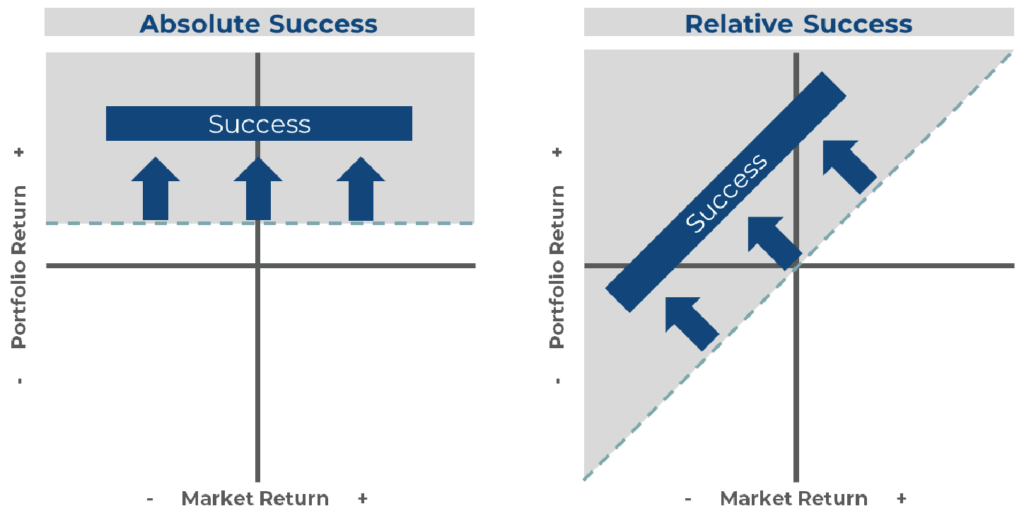

Statement dollars are like a scoreboard—one that can be checked every day. Their emotional characteristics are driven largely by two conflicting definitions of success: absolute success and relative success. Absolute success means setting a clear, immovable objective like a specific dollar amount or percentage growth. If portfolio returns exceed this objective, the investor can declare victory.

Relative success means evaluating portfolio performance compared to a similar portfolio or benchmark. For instance, many investment portfolios aim to outperform the S&P 500 Index. If the S&P 500 falls 2 percent, but the investor’s portfolio falls only 1 percent, this is considered a relative success. Because relative success has no absolute requirements, it can be measured in both up markets and down markets. However, it is important to remember the old Wall Street proverb that “you can’t eat relative performance.”

Both measures of success carry emotional risk because it’s human nature to want to outperform. A truly emotion-free portfolio—one that delivers absolute success in down markets and relative success in up markets—exists only in theory.

It doesn’t matter how much statistical modeling we do. Nothing can replicate, and no one can avoid, the emotional value of statement dollars. But each investor’s time horizon often determines how much emotional value they have. Thus, one piece of a financial advisor’s job is to keep investors focused on the long term. Like a fisherman pitching and rolling in a boat, watching the horizon can stabilize perspective.

The Spendable Dollar

Once a statement dollar is deemed spendable, its emotional value climbs dramatically. Statement dollars can rise and fall, but the spendable dollar (also known as cash) is king.

People feel real emotional pain when separated from their spendable dollars. That’s why the government withholds taxes before paychecks can be cashed. It’s why casinos use chips instead of real money. And it’s why companies encourage saving via payroll deductions. Once we feel a sense of permanent ownership over our spendable dollars, they’re much harder to let go of.

From an investment perspective, the emotional impact of a spendable dollar is often seen when an investment distributes income. Income is the least tax-efficient way to grow wealth, and taxable investors should nearly always choose unrealized gains instead.

Most investors view unrealized gains as statement dollars until they are sold or withdrawn. Then, they become spendable dollars and may feel more permanent.

While income-producing strategies can be an important part of a well-diversified portfolio, overexposure or a premature conversion of statement dollars into spendable dollars (like selling stocks) can significantly reduce the portfolio’s long-term value. Yet, the comfort of watching a spendable balance grow can tempt even the savviest investors.

The Spent Dollar

Generally, there is only one definition of a spent dollar. It is a spendable dollar we used to own, and now we don’t. This can be highly emotional. When dealing with spent dollars, investors often lose rational perspective.

Of course, not all spent dollars have the same value. We enjoy spending when it is voluntary and rewarding but usually not when we are forced to spend money on taxes, speeding tickets, or insurance premiums. These dollars often carry a sense of loss, and we commonly resist spending any dollar that has been hard-earned, diligently saved, or long-awaited. This resistance can lead investors to make imprudent investment decisions, but it typically makes an even bigger impact on planning.

Even if a strong foundation was established via theoretical dollars, the emotional roller coaster of statement dollars was successfully navigated, and the conversion to spendable dollars was perfectly planned, there is always a heightened sense of doubt when turning a spendable dollar into a spent dollar.

Why? Throughout the other three phases, time generally rewards you, healing wounds, providing flexibility, increasing options, and maximizing the power of compounding. But a spent dollar reverses the clock, turning time into an adversary by reducing future options. Nothing feels more limiting than a permanent decision, and spent dollars are spent, forever.

Navigating Emotional Values

Investing is emotional because saved money and long-invested assets often require sacrifice, patience, and persistence. These emotions can be clearly defined, and even predicted, but rarely avoided. To push back against the natural cognitive tendencies that lead to emotional decision-making, consider these four suggestions.

Be wary of using theoretical dollars to define risk tolerance. A risk profile that feels right with theoretical dollars will inevitably feel wrong when hard-earned statement dollars decline in value.

Attempt to prioritize which definition of success is most important to you, then manage statement dollars accordingly.

Try to resist the allure of spendable dollars from cash distributions. Even if they are reinvested into statement dollars, some portion will be spent on taxes. If they aren’t reinvested, you could miss out on future gains and still have to pay taxes.

Finally, when it is time to spend, spend. Enjoy the rewards of a successful investment journey.

The fear of running out of money is real and powerful. Consequently, many retirees fail to fully capture the value of their prudent historical decisions. A financial plan is a critical piece of the investment journey not only because it helps build wealth, but also because it can give you permission to enjoy what you’ve constructed. Remembering the differences among these four types of dollars can also be helpful, especially if it helps us mitigate our natural emotional connections.